Quilt Scholarship: The Quilt World and the Academic World

Quilt Scholarship: The Quilt World and the Academic World

by Lorre M. Weidlich

The study of quilts has attracted a wide variety of students of very different backgrounds and with very different goals.

Some have academic credentials, some do not. Ms. Weidlich here examines two contrasting groups who have studied and written extensively about quilts and quilting, comparing their methods, purposes and worldviews, and suggesting some reasons for their differences.

—Editors' Note in November, 1980, the American Quilt Study Group held its first meeting in Mill Valley, California. The following year, the papers presented at that meeting were published as

Uncoverings 1980.1

In 1974, the Folklore Feminists Communication devoted an issue to quilt research, including a bibliography of quilt literature compiled by two folklore graduate students. Several years later, two other folklore graduate students published a seminal paper on quilting in Southwest Folklore.

Three of these folklorists went on to write dissertations on various aspects of quilting.'

What do these two clusters of quilt-research activity have in common? The answer is, nothing. Not only is there no overlap between the people involved, the contexts out of which these activities grew are entirely different.

Different Roots

To determine the context in which "quilt scholarship," as exemplified by the American Quilt Study Group, developed, let's look at the credentials of the authors of papers published in the first volume of Uncoverings. Ten authors were included in the 1980 volume: one Ph.D., four M.A.'s, one

M.S., and four B.A.'s. Three are affiliated with museums; the

Ph.D. was director of a folklore archive. Authors' academic fields are not specified, except one who is described as having post graduate studies in textiles; the Ph.D., because of his affiliations (English department and folklore archive) can safely be assumed to have a degree in one of those subjects. Five are described as having published in or edited various popular periodicals such as Quilters Newsletter Maga-

zine, Nimble Needle Treasures, Craft Horizons, and Quilt

Journal. Other descriptions include "a quiltmaker since college years," "quiltings designer and consultant," "has exhibited her textile art widely," and "charter member of the Santa

Rosa Quilt Guild."3

This survey of credentials is obviously incomplete, since it seems to include primarily what each author considered relevant to establish her (or his) claim to being a quilt scholar. However, the general conclusion to be drawn from this brief summary is that the American Quilt Study Group was founded primarily by participants in what has become known as the "quilt world" along with a smattering of professionals whose fields (museum personnel, textile conservators, etc.) involve them with quilts, and only a very occasional scholar with academic training.'

Academic scholarship about quilting grew from different roots. Prior to the

1970's, there was little interest in quilting as subject matter. The rare journal article on the subject was romantic and casual, without analysis or conceptual struccontinued on page 2

ture.

5 By the early 1970's, however, quilting was "in the air," at least partially due to the increased interest in women's folklore and art. Quilting dissertations and papers began to appear during the 1970's and '80's, produced by scholars trained in analytic methods—e.g., semiotics, structuralism, and ethnography of speaking—appropriate to uncovering the meanings inherent in quilting.

Different Forums

The most striking thing about these two worlds is, until recent years and with notable exceptions, their almost complete separation.

6

Notable also is the difference in subject matter presentation, primary audiences, and critical frameworks.

While most academic scholars write or edit books, the most common presentation of research, the currency of the academic world, is the paper; these are presented at scholarly meetings, published in journals, or included in books of thematically-related papers. The thematic relationship is not necessarily the artifact or community analyzed in a particular paper. Papers about quilting may be grouped, e.g. on panels and in books devoted to women's folklore.' In the quilt world, there are more limited opportunities for presenting papers, so quilt world scholars often turn to books. As

Merikay Waldvogel points out, "Since Uncoverings does not have color photography and AQSG does not pay for articles,

AQSG authors turn to commercial publishers as an avenue to reach a much broader audience."'

The fact that these books are reviewed in such publications as Quilters Newsletter Magazine makes their primary audience apparent; few books by quilt world scholars have been reviewed by academic journals. The Quilts of

Tennessee: Images of Domestic Life Prior to 1930 is one exception: its review, in Southern Folklore, contained the following excerpts: "Its problems lie in two major areas: 1) the conceptualization of the project, and 2) the analysis and interpretation of the findings. To begin with, the notion of a statewide survey itself is problematic ... The arbitrary cutoff date of 1930 is also problematic ... Discussions are not developed and thus are not very convincing ... there is no drawing together of these bits of information into a coherent conceptual framework ... Even more disturbing, however, are the comments that reveal a lack of understanding of folk art."

9

Compare this to the Quilter's Newsletter Magazine review of the same book, which concluded, "This fine survey edition should be in every quilt library."

10

Obviously, the audiences of these two publications, as well as the reviewers, have significantly different critical perspectives.

Kristin Langellier confronts the issue of audience directly when she describes her experience of writing for Uncoverings:

"... writing for Uncoverings is tricky for me. My last abstract was ranked both first and last (yes!) among the submissions because it used very academic (and theoretical) language. 1 revised it considerably for publication, which I was amenable to doing. But I think that the question of "who's the audience of Uncoverings" is raised by your questions. On the other hand, there are different constraints in writing for academic and "general" audiences, but there's also how much disciplinary-specific language and concepts we can use writing about quiltmaking." Both she and folklorist Joyce

Ice describe the research in Uncoverings as "uneven." Quilt world scholar Pat Nichols, on the other hand, says about the papers in Uncoverings, "most have been excellent" and

Waldvogel comments "The editors have kept consistently high standards for AQSG authors, and I can count on the material being accurate ... My only concern is that the standards may be so high that they intimidate new authors."

The same difference in critical perspectives is apparent here.

Different Worldviews

The difference between these two groups of scholars transcends a disagreement over critical evaluations of the same scholarship, and suggests, in fact, differing worldviews.

Those who move in the quilt world refer to themselves as

"quilt scholars" or "quilt historians." Merikay Waldvogel states,

"Yes, I do define myself as a "quilt scholar" although my undergraduate degree is in French and my masters is in

Linguistics with a specialty in teaching English as a Second

Language." Pat Nichols says, "I define myself as a quilter and quilt historian." Academic scholars, on the other hand, tend to define themselves by their training. Kristin Langellier, despite having published several articles in Uncoverings, says, "No, I do not define myself as a "quilt scholar" because

I have other scholarly interests ... I define myself as a scholar of communication and performance studies, with a strong interest in women's studies." "No, (quilting) is not my only scholarly interest and for this reason, I don't define myself as a quilt scholar," states Joyce Ice. "I think it's a rather limited description. (Are there also 'basket scholars' and 'rug scholars?) I define myself variously as a folklorist, anthropologist, and museum person."

The fact that quilt scholars define themselves by their subject matter, without or despite academic training, while academically-trained scholars refer to their training, again suggests the different world which these two groups of scholars address. "Quilt scholar" is a meaningless label in the academic world, as Ice's comments quoted above make clear, while it is respected in the quilt world, a forum unconcerned with academic credentials.

Their views of what is needed in quilt scholarship also differ according to the world they inhabit. Waldvogel sees the biggest need as "integrating quilt research into the academic world" and states "I even think there is enough material available right now for a semester-long course on quilt history. For such a course, a textbook on quilt history should be compiled." This quilt world concern with documentation, the collection and compilation of factual material, contrasts with the academician's concern with theory.

Langellier says, "what concerns me most about the scholarship as a whole is what I see as a lack of theoretical and

critical perspectives on quiltmaking ... Often I find the research interesting but unconnected to larger questions about quiltmaking or women's culture. Why is a particular piece of documentary work significant, for example? How does it relate to previous research? How does it contribute not just to a particular knowledge base but also to theoretical understandings of quiltmaking?...I think, in other words, that the research has developed to a point where such theoretical and critical work is possible, necessary, and potentially exciting."

Two Paths to Empowerment

Patricia Keller, in her article "Methodology and Meaning:

Strategies for Quilt Study"

11

discusses the possible problems involved in scholars devoting themselves to the study of a

(primarily) female expressive form. Revising remarks of

Jonathan Holstein, she states, "quilt scholarship has been seen as a dead-end for all scholars for political reasons originating from a cultural perception equating female with inferior."12

Curiously, the women who do research on quilting, whether quilt scholar or academically-trained scholar, are uniform in their disagreement that quilt research is a "dead end." Langellier says, "I have just been promoted to Professor and my quiltmaking research was part, although not all, of my publication record." "The popularity of quilts, and books about them" explains Joyce Ice, "has allowed me to pursue research for a museum exhibition and an accompanying publication, funded by grants from NEA and the New York Council on the Arts, and has also given me the opportunity to consult on other projects involving quilting and/or women's traditional arts. Because I have situated my research in a women's studies/feminist theory framework, I have not encountered any major difficulties."

13

Of the quilt world side, Pat Nichols says, "Negative impact...not enough hours in the day...Friends

are often surprised by what I do, my activities need to be explained and defined but I have never felt they feel it trivial or unimportant." Waldvogel points out the tremendous success she has had with her work: "my quilt research has received much more attention than my linguistics work ... My reputation grew because I was in print...From that first positive experience, I went on to write more articles and books."

It would appear that, within their respective forums, neither quilt world scholars nor academically-trained scholars have been held back by their choice of subject matter. Both of these parallel routes seem to have led to empowerment for the women pursuing them, leading me to cite the model which I believe puts both in perspective.14

Anthropologist Michelle Z. Rosaldo, after examining the universal structural inequality between the sexes and determining that the male consistently has inhabited the public sphere and the female the domestic one, suggests that there are two ways for women to gain power: move into the male dominated public sphere, or establish a female public sphere.

In Rosaldo's words, "(Women's) position is raised when they can challenge those claims to (male) authority, either by taking on men's roles or by establishing social ties, by creating a sense of rank, order, and value in a world in which women prevail.

One possibility for women, then, is to enter the men's world or to create a public world of their own."

15

Compare Rosaldo's description of a women's public sphere to the comments of

Merikay Waldvogel: I have often wondered at the success I have found in the quilt world... I think it is because this field had no rules governing it. Without any rules in place, women felt free to step into it and find their place. Today there are hundreds of quilting instructors, judges, writers, editors, curators, collectors, business owners, inventors, etc."

Waldvogel's description confirms that quilt scholarship is one role in a complex women's sphere providing multiple opportunities for empowerment for the women who inhabit it, no less than the pursuit of a career in the (formerly maledominated) academic world empowers the women who choose that route and accept the standards of that world.

This suggests that the function of quilt scholarship within the quilt world is expressive. Self-definitions like "quilt scholar," meaningless to academicians, provide a recognizable and respected role for women who so define themselves within the quilt world. Likewise, the concern with what Langellier refers to as "the documentary impulse that animates much of the (quilt world) research" becomes understandable as the attempt to construct a history which legitimizes and reinforces a particular worldview. Ultimately, it is an examination not so much of the content of quilt world scholarship as of its existence and the value system that informs it that will teach us most about the meaning that underlies the world of quilting today.

Dr. Lorre Weidlich has both academic and "quilt world" credentials. She has a B. A. from the University of Michigan and an M. A. and a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at

Austin, all in Folklore. Her 1986 dissertation was the first devoted to the current quilt revival and its associated culture.

She is also a quilter and designer, quilt teacher and lecturer, exhibition -organizer, etc. Her writing on quilts has been published in both academic and popular publications. Her anomalous relationship to the quilt and the academic worlds gives her a vantage point from which to practice the metascholarship presented in this article. Since finishing graduate school, she has pursued a non-academic path, but is moving back into the world of scholarship, with an emphasis on research on quilts and quilt culture.

The Cultural Construction of Quilts in the 1990s

by Elaine Hedges

The cultural context of quilts and quilting, past and

Present, is of increasing interest to scholars in a number of fields. Professor Elaine Hedges has written extensively on the subject, exploring especially the place and meanings of quilts

in women's lives. Here she reviews for The Quilt Journal three papers presented at "Tradition and Change: The Cultural

Traffic in Quilts," a session included in last fall's American

Studies Association meeting in Boston.

—Editors' Note

The contemporary quilt revival is estimated to involve at least 15.5 million people in the United States alone, from quiltmakers, collectors, and exhibit-goers, to quilt historians, estheticians, and theorists.' So much has by now been written about quilts, and so widely available have they become, that the quilt has entered the popular imagination as a new cultural icon, replacing the melting pot as the metaphor that seems best to describe the nation. Indeed, the quilt is by now the site—and often the contested site— of what sometimes seems to be an endlessly proliferating array of esthetic, ethical, political, and social meanings.

"Tradition and Change: The Cultural Traffic in Quilts," was the title of a session held November 2, 1993 at the annual meeting of the American Studies Association in Boston,

Massachusetts. Its purpose was to explore and assess some of the ways in which the quilt is currently being culturally constructed. The session drew an audience that included folklorists, students of material culture, art historians and literary scholars and theorists—a mix that attests both to the academic interest in quilts and the interdisciplinary nature of quilt study; such cross-field enrichment is a goal of the

American Studies Association.

The session consisted of three presentations: "Romancing the

Quilt: Feminism and the Contemporary Quilt Revival," by Elaine

Hedges, Towson State University; "(Re) Narrativizing the Textile

Text: Quiltmaking as Autobiographical Act of Resistance," by

Jane Przybysz, University of South Carolina; and "Marketing an

American 'Heritage': The Smithsonian Quilt Controversy" by

Judy Elsley, Weber State University. Collectively the papers discussed both traditional and recent interpretations of the quilt in order to assess, and problematize, those interpretations.

"Romancing the Quilt" described feminist response to the quilt since the early 1970s, and especially new uses of the quilt metaphor by feminists that have emerged in the last few years. Feminists have embraced the quilt at least since Patricia

Mainardi's ground-breaking article, "Quilts as an American

Art," first appeared in 1973.

2

They have found in the quilt such a range of empowering meanings that by 1983, ten years after Mainardi's article, art critic Lucy Lippard could state that the quilt had become "the prime visual metaphor for women's lives, for women's culture."

3

Quilts were seen as validating the dailiness of women's lives and their unappreciated household labor; their scrap content was seen as analogous to the often fragmented, interrupted nature of those lives; the quilt's repeated block structure, read as nonlinear and non-hierarchical, attested to feminist ideals of equality; and the cooperative work methods of the quilting bee celebrated mutuality and cooperation among women.

Further, both as bedcovers that provided warmth and as ceremonial gifts, quilts testified to an ethic of nurturing and caring—female values that in the 1970s were being rediscovered and reclaimed. Finally, the very process of making a quilt—combining separate, disparate pieces of cloth into a new whole—powerfully served as symbol for the new wholeness and unity, both individual and collective, and the new political solidarity that feminism espoused.

In the last few years feminist use of the metaphor has escalated, and the quilt has become an even more privileged explanatory paradigm, applied to a broad range of contemporary concerns both within and outside the academy. The terminology, designs, construction techniques and production processes associated with the quilt have provided feminist scholars and theorists with their key analogies for all of the following: the history and traditions of American women's writing: African-American women's literary traditions and an

African-American female esthetic; feminist literary theory and criticism; women's studies courses and programs; curriculum transformation projects designed to gender-balance the curriculum and to expand the literary canon to include the works of women and minorities; feminist pedagogy; women's spirituality; mother-daughter relationships and family relationships; the nature of female maturation; women's ways of thinking, knowing and creating; postmodern theories of the construction of the self; and, implicit in many of the above but warranting special emphasis, current feminist concern with issues of diversity, multiculturalism and difference.

Hedges illustrated these new metaphorical applications with slides showing the extensive use of quilts and quilt patterns on the covers of books and journals devoted to many of the above topics. She also examined the rhetoric in such publications, where quilting terms and techniques, such as piecing and joining, block structure, working with scraps and incorporating diverse fabrics and designs into a quilt, regularly provide explanatory frameworks.

While such a broad range of applications can be seen as a tribute to quilts as extraordinarily resonant objects of

The Construction of Quilts in the 1990s

continued from page 5 women's work and art, Hedges was concerned to caution against what may begin to be metaphorical overload. Many of the contemporary metaphorical uses are oversimplified and over-generalized. Others are based on serious historical inaccuracies or an ignorance of quilt history that reveals the extent to which such history (despite the good attendance at the ASA session) is still not considered in the academy a sufficiently important or prestigious subject for scholarly research. Finally, the especially popular use of the quilt to celebrate diversity and multiculturalism—the quilt's disparate fabrics combining to form a harmonious whole—may risk implying easy solutions to difficult problems, overlooking the intransigent nature of many racial, ethnic, and class differences, so that the quilt becomes a nonverbal image that obscures real dissension. Many of the current mataphorical uses of the quilt, Hedges concluded, constitute a new romanticization of quilts, at the very time that quilt scholars are trying to release the quilt from sentimentalities inherited from the past.

Past as well as present cultural constructions of the quilt, including ways in which the quilt has been romanticized, were the subject of Jane Przybysz's presentation, which combines historical research and analysis with the use of a performance studies approach to quilts. Przybysz described the purpose of her presentation as that of "facilitating the processes of deconstructing popular notions about quiltmaking in America, reconstructing a genealogy of quiltmaking as historically-specific material and symbolic practices, and theorizing the ever-shifting and elusive dialogical relation between the making of objects [and] the making of meanings."

Her presentation was in two parts. The first consisted of a series of dramatic monologues—original poems recited against a background of quilt slides and presented as a way of restorying her own personal engagement with quilts. The poems were intended, as her paper's title indicated, as acts of "autobiographical resistance," a counter-narrative to stereotypical responses to quilts as, for example, merely comforting objects in times of bereavement, loss and death or unproblematized tokens of love. They were experiments in shifting and complicating the present terms of quilt discourse.

This purpose also informed the second half of Przybysz's presentation, which offered a feminist analysis of two nineteenth-century quilting "texts": the quilting party described in

Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1859 novel, The Minister's Wooing, and the quilting staged by women in a reconstructed New

England kitchen in 1864 at one of the Sanitary Fairs held in the North during the Civil War to raise money for war relief.

Both the scene in Stowe's widely-read novel and the Sanitary

Fair performance, which may have been inspired by it, offered nineteenth-century white middle-class women,

Przybysz argued, spaces within which they could question and at least temporarily free themselves from the restrictive definition of "femininity" of their culture. Stowe's novel described an eighteenth-century quilting party placed in a New England kitchen, which positioned women at the center of the social, intellectual and political life of their community. The loose colonial costume worn by the women during the Sanitary Fair enactment, the informal speech they adopted, and the public space they occupied during the performance all similarly provided them with a way of momentarily redefining themselves and breaking free of gender and class restrictions.

Imaginatively liberating as both Stowe's and the Sanitary

Fair's quilting performances may have been, however, Przybysz concluded that both were romanticized and idealized presentations. What we know of actual colonial quiltings doesn't support Stowe's description. What is important is to recognize the ways in which Stowe's novel, and nineteenth-century stagings of quilting parties and New England kitchens (stagings which took place at other Sanitary Fairs as well), have shaped and continue to shape popular conceptions of the "tradition" of quiltmaking in the United States. Thus, as Przybysz noted,

"the first history of quiltmaking published in America, Quilts:

Their Story and How to Make Them (1915) by Marie Webster, ends with an eleven-page passage excerpted from The

Minister's Wooing quoted as ethnography, not fiction. Yet

Webster's book continues to be read uncritically, and quoted vigorously, by quilt scholars and feminists alike."

In "Marketing an American `Heritage'," Judy Elsley, like

Hedges and Przybysz, also explored the ways in which the meanings attached to quilts are culturally produced. Her paper examined the controversy over the sale by the

Smithsonian Institution in July 1991 of licensing rights to 100 of its "heirloom" quilt designs to American Pacific Enterprises, to be mass produced in China and marketed through mail order catalogs and department stores. The sale created unprecedented controversy among quiltmakers, quilt collectors, quilt marketers, and quilt historians. Given that museums have been routinely selling reproductions of their works since at least the 1960s, why did the prospect of marketing reproductions of Smithsonian quilts elicit such protest? One group of quilters charged that the reproductions amounted to the "cultural thievery of an American heritage."

In documenting the controversy, Elsley observed that it addresses "how we perceive quilts, what purpose we think they serve, and the cultural meaning we assign them," and that the controversy thus focused attention on some of the most pressing issues in contemporary quiltmaking.

The reproductions, she argued, generated such controversy because they enact a series of disturbing cultural dislocations or shifts in our perception of quilts: a shift from the control of quilts by their makers to control by commercial enterprises; from focus on the quiltmaker or the process of creation to focus on the product; from the quilt embedded in its historical and cultural conditions to the quilt isolated and

even alienated from that context; and a shift from the quilt as art to the quilt as craft or as mere merchandise. Each of these shifts, Elsley argued, represents a slippage that undermines the efforts of quilt scholars and enthusiasts to give quilts, and the women's culture they represent, their rightful place in American culture. The Smithsonian controversy, she therefore concluded, represented a struggle over women's history, its place, purpose and significance.

Thus, quilters often framed their outrage over the reproductions in terms of a sacred violation, the loss of what could be described as the quilt's "aura." This term, coined by Marxist philosopher Walter Benjamin, refers to that combination of uniqueness and context which is essential to any work of art.

Aura, Elsley claimed, is particularly significant in the case of quilts because these textiles often represent women's texts, sometimes their only way of speaking, telling their stories, and recording their existence. To place a quilt in its context, to acknowledge its aura, in other words, becomes a way to reclaim women's history. When quilts are stripped of this context we lose their textuality, and thus women's history and culture are lost as well.

Elsley recognized that there may be valid reasons for reproducing historically important quilts. Reproductions may inspire artists, educate the general public, and make available to a large audience what in the original would be accessible only to an elite. On the other hand, such reproductions may also undermine the quilt's meaning as art. Elsley again cited Benjamin, who has argued that the mechanical reproduction of art changes society's reaction to that art because the unique becomes the conventional, and "the conventional is uncritically enjoyed." We react en masse to reproductions, says Benjamin.

In the case of quilts being marketed as "heirlooms," Elsley suggested, this en masse reaction may lead to the confirmation of nostalgic myths about an "America" long gone, one that in fact probably never existed.

The mass reproduction of the Smithsonian's quilts also has economic implications that were raised and debated during the controversy. Cheap imports threaten what is still a somewhat shaky quilt cottage industry in the United States; and many protesters were concerned over the possible exploitation of low-paid Chinese female labor, an exploitation that creates conditions—the anonymity of the worker, oppressive working conditions, lack of control by the worker of the product— representing a return to a cultural status women have long fought to escape.

The Smithsonian controversy, Elsley concluded, thus dramatically demonstrates how the quilt has by now become far more than a material object; it has become a major cultural concept. Her examination of the controversy thus corroborated the findings of the other two papers in the ASA session.

Together, all three papers provided rich and provocative analyses of many of the major ways in which quilts are being culturally constructed in the 1990s. That some of those constructions, or reconstructions, may be open to question on historical or other grounds, as both Hedges and Przybysz argue, is not to deny the profound impact quilts have had and continue to have on the cultural imagination. The papers, it is hoped, will serve to extend, and usefully complicate, the current cultural conversation about quilts.

Elaine Hedges is Professor of English and Director of

Women's Studies at Towson State University, Baltimore Maryland. She is the author or editor of many books and articles on women writers and women's quilt culture, including the

text for Hearts and

Hands, the Influence of Women and

Quilts on American Society (Quilt Digest Press, 1987).

The Victorian Crazy Quilt as

Comfort and Discomfort

by Jane Przybysz

The significance of quilt making and other needlework to the women who accomplished it and the societies in which it was made, has been discussed for some centuries by both observers and practitioners of the crafts. For some who sewed it was elevatintg and ennobling, for others it was apparently largely drudgery. Very few accounts, however, looked at the implications of quilt making for women's roles and societal change. Thus the discovery by Jane Przybysz of the unpublished musings of an accomplished female writer who used the crazy quilt, an icon of Victorian ideals, as the central symbol in a discussion of changing values, is of unusual importance. Ms. Przybysz here publishes the manuscript for the first time and discusses some of its implications.

—Editors' Note

In the spring of 1993, while visiting the Manuscripts Archives at Tulane University's Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, I happened upon a hand-written text by Ruth McEnery Stuart titled "To Her Crazy-quilt...A Study of Values." I glanced briefly at the work, noted its considerable length, and marveled that it was written circa 1900 as a soliloquy charting a mother's shifting perception of what it meant to have spent a year of her life creating a crazy quilt. Before leaving the

Archives, I ordered a copy.

Waiting for the copy to arrive by mail, I wondered who

Ruth McEnery Stuart was, and why she apparently never finished this piece. What might her dramatic monologue contribute to our knowledge of late 19th century crazy quiltmaking practices, or of the meanings turn-of-the-century quiltmakers attributed to the crazy quilts they made? How did

Stuart's text compare with contemporaneous narratives prominently featuring crazy quilts? And finally, how might "To Her

Crazy-quilt...A Study of Values" help explain the rise and fall of the crazy quilt fashion in the United States? These were the questions "To Her Crazy-quilt" implicitly posed, and which I will address in this introduction to a transcription of

Stuart's hitherto unpublished text.

The first of eight children born to a wealthy Louisiana planter's family in 1849, Ruth McEnery grew up in New

Orleans, regularly visiting the family's Avoyelles Parish plantation.' Little is known about her early life, though she apparently attended both public and private schools in New

Orleans until the onset of the Civil War, which significantly depleted the family's fortunes. In its aftermath, Ruth took a job teaching primary school and apparently assumed responsibility for much of the family's housekeeping, cooking, and sewing.

In 1879, McEnery visited a sister-in-law living in Arkansas.

There she met and married a well-established cotton planter and three-time widower, Alfred Oden Stuart, after knowing him for only three weeks. Writing about McEnery's unusually brief courtship, Helen Taylor posits that the move may have been "a desperate attempt to escape the heavy demands of home life in New Orleans" (91).

As Stuart's fourth wife, Ruth settled into a comfortable life in a colonial house on her husband's vast plantation, where former slaves and poor whites were employed as domestics and field hands. Three years later, she gave birth to a son,

Stirling. Only a year later, however, her husband died without leaving a valid will. Shortly thereafter, Ruth returned to

New Orleans to live with a sister, and began writing to support herself and her son. It appears that the claims of children born to her husband's three previous wives may have superseded those of Ruth and Stirling, leaving them in reduced financial circumstances.

Several years later, while vacationing with her son in

North Carolina, Stuart happened to meet Charles Dudley

Warner. Then editor of Harper's Magazine, Warner would bring Stuart national acclaim as a writer of "local color" stories—humorous and sympathetic tales of southern blacks and "hillbillies" she claimed to have studied on her husband's plantation, and of Italian, Cajun, and black folk she had encountered in New Orleans. By the early 1890s, Stuart had moved to New York City where she traveled in artistic and literary circles that included the grand dame of the decorative arts movement, Candace Wheeler, and her daughter Mrs.

Keith, and writers such as Mrs. Margaret E. Sangster, Mary E.

Wilkins Freeman and Kate Douglas Wiggin, all of whom took up the crazy or patchwork quilt as a theme at some point in their writing careers.'

By the turn-of-the-century, Ruth McEnery Stuart had established herself as one of the three most successful female writers of "local color" fiction from Louisiana, sharing that honor with Kate Chopin and Grace King. Her sister, Sarah, had joined her in New York, serving as surrogate wife to

Ruth and mother to Stirling, enabling Stuart to write, travel extensively giving dramatic readings, and participate in the activities of the Barnard, MacDowell, and Wednesday Afternoon cultural clubs.

While "To Her Crazy-quilt" was one of any number of dramatic monologues Stuart composed, it differs markedly from the majority of the writing for which she became well known in that it is not of the "local color" variety, set in the

South and featuring persons unlike herself. Rather, "To Her

Crazy-quilt" appears to take up the problem of a woman of

Stuart's own class and race. This may help explain why the

monologue was never completed or published. Stuart may have felt its subject matter would discomfort readers who had come to expect less serious fare about "other" folks. And unlike earlier pieces by Stuart which had focused on white, middle-class women's lives—"To Her Crazy-quilt" did not rely on humor or heterosexual romance to bring the story to a satisfying sense of closure.

Having found no evidence confirming she ever actually made a crazy quilt, I have not been able to determine if

Stuart based "To Her Crazy-quilt" on personal experience.3

When popular women's magazines started mentioning crazy quilts in the early 1880s, however, Stuart would have been positioned financially and socially, as the leisured wife of a wealthy planter, to undertake the making of a crazy quilt.4

Hence, it is quite possible that the monologue documents the initial stages of Stuart's own transformation, in the aftermath of her husband's death, from a middle-class wife and mother to a professional writer and public speaker.

It is just as likely, however, that by the time she drafted the dramatic monologue, circa 1900, Stuart conceived of the crazy quilt as a metaphor for the imagined space she and other female writers and artists had negotiated for themselves. It was a space that was neither the private, "feminine" world of love and ritual which Carroll Smith-Rosenberg has so aptly described (and of which fancywork was a marker), nor the public, "masculine" world of reading, writing and speaking to which the "New Woman" sought entry. Instead, it was a space between the so-called separate spheres, or a hybrid of them both.

Compared with other late 19th century narratives in which crazy quilts play a central role, "To Her Crazy-quilt" is unique both in form and content.' To my knowledge, no other account takes the form of a soliloquy in which a quiltmaker speaks aloud to her crazy quilt or to herself.

6

No other 19th century story involving crazy quilts features a protagonist who is a mother, presumably a married woman, reflecting at length upon the ways a crazy quilt and other needlework have figured in her life. Contemporaneous stories featuring crazy quilts most frequently portray young unmarried female protagonists tied to plots which turn on whether the boy wants or gets the girl who makes a crazy quilt. No other story articulates, but fails to resolve, the intensely ambivalent feelings a crazy quilt occasions its maker.

To my mind, the 19th century crazy quilt text with which

"To Her Crazy-quilt" most resonates is that reported by

Jonathan Holstein in The Pieced Quilt: An American Design

Tradition (1973) as having been applied directly to a crazy quilt. "[E]mbroidered on a simple black velvet patch, in the midst of the most incredible profusion of textures, colors, embroidered animals, plants, and countless 'show' stitches," the text read "I wonder if I am dead" (62). This one sentence suggests that the process of creating a crazy quilt had perhaps led its maker to a startling self-awareness.

The protagonist of "To Her Crazy-quilt..." explicitly characterizes the experience of making a crazy quilt as one of personal transformation—of coming to a new consciousness and self-awareness. The crazy quilt represents those very

"irresponsibilities" which enabled her to see her way "to better things." Something about the process of making the quilt enables the narrator to see herself and her needlework from a new perspective.

What "the better things" were to which the protagonist referred is not exactly clear. But the language Stuart used to set women's fancywork in opposition to nature's beauty, objects made for "use," and women's pursuit of a liberal arts education, indicates her notion of "the better things" was shaped by two things: the advent of a modernist, utilitarian aesthetic in home decoration spawned by the arts and crafts movement, and a backlash against the Victorian feminine ideal, particularly its sentimentalization of motherhood.

As Virginia Gunn has noted, by the late 1880s the home decorating tastes of trendsetters like Stuart's New York City neighbor Candace Wheeler had shifted. These women increasingly rejected the ornate, detail-oriented, and often oriental-inspired fancywork that crazy quilts typified in favor of objects that incorporated simple, streamlined, arts and crafts movement or "colonial" designs.' Objects whose forms were perceived as an outgrowth of their functions, patterning themselves after things as they were formed and found in

"nature," increasingly displaced as "fashionable" those which were perceived as merely "ornamental." Turn-of-the-century feminist and progressive educators' faith in rationality, science and technology as keys to social progress buttressed this shift in home decorating trends.

The formation of women's clubs devoted to promoting women's cultural achievements, particularly to creating opportunities for white, middle-class women to acquire the liberal arts education previously reserved primarily for more affluent women and men—also appears to have contributed significantly to the devaluing of Victorian fancywork in the last decade of the 19th century. Proponents of woman's suffrage, dress reform, and home economics all sought to distance themselves from images of sentimentality and feminine excess they associated with Victorian fancywork. Prosuffrage writer Eliza Calvert Hall, for example, had the protagonist of her book, Aunt Jane of Kentucky, reject the crazy quilt in favor of traditional "colonial" designs. As a strong supporter of women's rights and suffrage, as well as a member of several literary clubs, Stuart would have been very familiar with many club women's arguments against woman's role as mere "ornament," and against the ornaments, like crazy quilts, which had come to signify Victorian femininity.'

"To Her Crazy-quilt" also suggests that a fear of female sexuality may have contributed to the decline in the fashion for crazy quilts, and underpinned this shift in home decorating aesthetics towards a valuing of "clean" colonial or modernist designs. In her defense of the crazy quilt, Stuart's narrator refutes accusations, popularized by women's magazines, that the quilt is "guilty of profanity," and "vulgar." In

The Victorian Crazy Quilt as Comfort and Discomfort

continued from page 9 her critique of the quilt, she likewise points up its "irresponsibilities," particularly its status as a "mistress" who is not

"true." All of these terms may indicate that the crazy quilt fell from favor, at least in part, because it came to be associated with moral impropriety and illicit female sexuality. Also, if the quilt was a "mistress"—true or not—its maker implicitly was a "master." So it may be that women increasingly shunned undertaking the making of crazy quilts because such quilts came to connote "masculine" ambition.

While 19th century females were generally encouraged to hone their needlework skills as a sign of industry and submissiveness, some concern was expressed by members of the medical community at the turn of the century that the relationship between women and needlework, and women and fabric, was perhaps problematic. Freud and Breuer, in their Studies On Hysteria (1893-1895) noted that the hypnoid states their female patients experienced seemed "to grow out of the day-dreams which are so common even in healthy people and to which needlework and similar occupations

[repetitive, monotonous chores] render women especially prone."(13) They found that physically restricted and emotionally constrained women who were intellectually curious and ambitious in ways considered "unfeminine" often indulged in systematic day-dreaming of the sort they might experience when engaged in needlework. And it was in the context of this day-dreaming or "private theater," where thoughts highly charged with affect apparently escaped regulating and normalizing cultural narratives, that they became "ill."

Then, shortly after the turn-of-the century, French psychologist Gaetan Gatian de Clerambault published an essay,

"Women's Erotic Passion For Fabrics," in which he described the cases of three hysterical women between the ages of forty and fifty whose passion for fabric and "useless" objects of feminine adornment had led them to shoplift from department stores. He found them to be frigid in heterosexual contacts, but fully capable of satisfying themselves sexually by fondling fabric or rubbing it against their bodies. For these women, fabric served as a stand-in for their own bodies or that of another—often an idealized "maternal" body—to which they could safely surrender both identity and agency.

In other words, some women's passion for the trappings of femininity purportedly aimed at attracting and pleasing a man, in fact afforded them erotic self-sufficiency, intense narcissistic pleasure, and maternal comfort.

This increased wariness regarding the (homo)erotic pleasures and narcissistic self-sufficiency needlework perhaps afforded some women may help explain why, for example,

Dulcie Weir resolved her short story, "The Career of a Crazy

Quilt," published in the July 1884 issue of Godey's Lady's

Book, with a double wedding. The two young middle-class female friends, protagonists of the tale, are completely caught up with making crazy quilts, particularly with trading samples of fabric and embroidery motifs and with the challenge of acquiring different bits of silk. One alienates her fiance through what he perceives as her aggressive, unfeminine, and morally-tainted efforts to obtain silk from any number of male acquaintances. The other schemes to obtain free scraps of fabric from department stores by illegal means. By ending the story with a double wedding, whereby the first girl is reunited with her fiance and the second weds an employee of the firm she had attempted to defraud, Weir effectively neutralized the threat crazy quilts presented to the social fabric, particularly to the heterosexual contract and dominant cultural constructions of femininity that arguably constituted the warp and woof of that fabric. Rather than have her heroines remain intimates with one another as "slaves" to their crazy quilts (as the anonymous but apparently male author of an 1890 poem "The Crazy Quilt," published in the

October 25, 1890 issue of Good Housekeeping, observed of all makers of crazy quilts), Weir turned them into slaves of the more socially acceptable kind—compliant and obedient, middle-class wives.

While it would seem I've strayed far from the text of "To

Her Crazy-quilt," I want to suggest that the narrator's continued attraction to her quilt, her ability to be "charmed" by it, and her ultimate retreat to its comfort at the end of the monologue— despite her consciousness that it had come to represent a

Victorian feminine ideal to which she no longer fully subscribed—might be understood in light of the role crazy quilts, fabric, and other forms of needlework played in the erotic and emotional life of late 19th century women. For professional women like Stuart who, to stay in the good graces of her publishers and the public, played the role of the morally irreproachable, hardworking, ever cheerful hostess and southern lady, a crazy quilt may have been one of the few sources of sensual pleasures in which she might guiltlessly indulge.

Even more important, perhaps, for the bright, ambitious woman who, like Stuart's fair protagonist, found her various

"culture-schemes" forever stalled by the arrival of yet another set of "pink feet," a crazy quilt might have been the poem, the mother, and surrogate lover whose making and presence occasioned self-reflection, and provided the sense of pleasure, autonomy, and assurance which gave her the courage both to see her way to better things, and to see familiar things—particularly her own needlework—in new ways. For the home-bound wife and mother, the crazy quilt may have been the "private theatre" in which she first heard herself speak aloud that which had been unspeakable.

In the end, what is most important about "To Her Crazyquilt," is not its status as fact or fiction. The piece stands as a record of how an affluent southern wife and motherturned-professional writer and New Yorker made sense of the fashion for crazy quilts. Drawing upon the rhetorics of a number of aesthetic and social movements, Stuart con-

structed one mother's experience of making a crazy quilt, offering both a critique and a defense of how needlework functioned in white, middle-class women's lives at the turn of-the-century .'

To Her Crazy-quilt...A Study of Values by Ruth McEnery Stuart

"Yes, I suppose you continue to be beautiful, my quilt, even after the day of the ordinary crazy-quilt is past. The truth is I put my best self into you. You were to me—before I waked from the delusion—my one poem, the first form in which something within me seemed to find full expression.

There is not—as has been said—an inharmony [sic] about you. The scraps of silk of which you are composed actually fit, and their colors are never guilty of profanity, one to another."

You began to grow from the top left-hand corner and zigzagged with consistent irregularity until the bits of green in your south-Eastern extremity fit precisely into the violet fragment above it—completing the square and the color marvel.

There is no point at which a triangle or parallelogram throws a corner or side vulgarly over its neighbor's territory.

Each color holds its individual place just as distinctly as those of a Kaleidoscope in any given combination or as the bits that compose a mosaic."

Were you transparent as the glass panes of a cathedral window, your exquisite intricacy of composition would become only more apparent. The thing you seemed to express, as you grew beneath my fingers were beauty and harmony and a sort of perfection, to attain which is always a delight to the composer, be he architect, musician or simply a sewer of patches, as was 1.12

He who works to an end making a multitudinous detail conduce to the forming of a graceful unit is, in so far as he succeeds, an artist.

If the unit express [sic] a worthy thought—if the thought declare itself only, in a caressing restfulness to the eye, it is thus far soul-satisfying."

He who touches the human soul, ever so faintly—as to wake it to [momentary] consciousness of being—is he not a poet. And his medium of expression?" Ah! are you not my poem my pretty pretty quilt?"

The speaker was a fair dark eyed woman and she sat alone before a combination of brilliant patches, the work of her own hands."

Pausing here in her soliloquy, she sighed heavily.

"So you seemed to me[,]" she resumed presently[.] "So you seemed to me, my silken wonder, until so short a time ago it seems only yesterday."

Only yesterday—only the day before the today of my new consciousness—and in the fresh clear dawning, how you are transformed!"

The mark of a year—a whole, full rounded cycle, with all its golden moments open to all that time can sieze [sic] or.

hold, is put into this miserable inadequate expression of what any half-clouded morning sky may put to shame—even a dreary wintry sunset cover with confusion."

The [jilting) blaze that spurts about my fire of smouldering logs gives more pleasure in its brief twinkling life—a glowing autumn leaf with its defiant denials of the subsidence of life within its veins is to you, my poor patchwork quilt, as a song from a poet's throat compared to a jingling rattling doggerel.20

But why have you thus ceased to charm me, my pretty quilt? I look and see that you are, as I meant you should be, your own best expression of art, and yet you are no longer a pleasure. No longer are you to my fond eyes a Kaleidoscope's color-marvel—a symphony in hap-hazards—a poem of complements.

You are a map— Ah me, a map of my own ignorances.

For a whole year I buried my energies in this poor thing, energies obedient to my will and that might have been profitably bent toward some worthy acquisition of knowledge.21

I know not the German tongue nor the speech of Italy.

Dante the divine is mine only through inadequate translation.

Each brilliant patch in you, my poor color study, has become a province in the great map of my state of ignorance.. They are German lessons unstudied—Italian poems unlearned history forgot.

The golden thread that connects while it defines them is the whole year—the golden stream of time.

This golden demarkation [sic] made of you, my quilt, a unit expressing harmony.22

On my map it is a definer of barren fields and it means unculture. It is a gleaming boundary of untilled lands.

Quilts are good to make, to have, to keep, and time well spent in their weaving when one is cold or his brother in need of warmth. The tedious stitching of intricate shapes fitted to a [mat] might be worthy work were time eternity with infinite space for all finite or infinite Endeavors.

23

It is in time with all its brevity fitting employment for the feebleminded.

24

[B]ut when one's days are short and it takes three score years to half-learn what others have thought or spoken or done is it not a pity to consume the ten years left for individual progression in sewing patchwork?

And yet—and yet I would not part with you, my crazy, crazy quilt, for in your very irresponsibilities I have been able to see my way to better things. You are newly cataloged in the book of my regard as one of a despised family.

25

Fishscale jewelry, flowers of wool and waxen fruits are your near of kin. Yes I grant you are the flower of your family, my quilt, but of the same strain.

26

The strawberry mark is upon you—you cannot deny your blood. Such are your companion diverters of energies, consumers of time, betrayers of true art.

"Art is long and time is fleeting," and if in the whirlagig

The Victorian Crazy Quilt as Comfort and Discomfort

continued from page 11 we seize her for our mistress, let us see to it that she be true.

Let us be sure that in making a careful estimate of its values we take into life the things most worthy, discarding for want of time, lesser considerations. And away with false art!

While I sit and gaze upon you, my quilts, you seem to change into a mirror and straining my eyes I see myself sitting before you while over my shoulders hover a cloud of ghosts.

27

Long white headless things come and go and come again. They are richly embroidered garments and—ah me, how I recognize the stitches, every one my own!

And now I understand. They are ghosts—the departed phantoms of tediously wrought undergarments of fine linen— an "odd-moments" series of early follies and they are come to haunt my latter-day ignorances.28

A certain intricate device—how I remember the moments that oddly indeed ran to hours while I criss-crossed and darned in the firmly drawn threads 29

I shall call this my Carlyles French Revolution which to rend and study demanded a thieving of time from other things[.]30 And you, with your little square-set yoke all done in whirls, Yes, I know you. [Y]ou are "Mortry's Dutch Republic" which—must I own it? —Even yet I but half know. Babies have come with the years and put their little pink feet firmly down upon so many of my culture-schemes.

31

But why particularize?

If one need to make a quilt let her see to it that it be welldone, soft warm, pleasing to the eye. [Glut let her not deceive herself with so inadequate a medium, into attempting to express more than a good coverlet.

The perfection of art in articles of use is first to have them suggestive of their object.

The highest art in the planning of a life consists in so considering its values as to subordinate or even to exclude much of the detail that so mars many of the canvases upon which some of our noblest figures are cast.

The fond young mother who sits, one foot gently stirring the cradle while she tediously knits lace for the petticoat's hem of her babe, adds with her knitting nothing to his well being.32

The culture she might be gleaning the while she works would broaden and lift his growing life to higher things.33

So comes a swarm of reflections inspired by your much abused presence—my quilt—my "comfortable" that despite the odium I have put upon your face, are soft and light and warm.34

Let me draw you over my shoulders, folding in and forgetting your crazy patches, and go to sleep.35

Performance Studies at New York University. She gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Dr. Wilbur Meneray, Head of

Special Collections; Sylvia Metzinger, who served as the Acting

Head of Special Collections in Dr. Menaray's absence; Leon

Miller, Head of Manuscripts; and Courtney Page, Administrative Assistant at the Tulane University Library.

Jane Przybysz works at the McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, as the Principal Investigator on the Southeastern Crafts Revival Project, a National Endowment for the

Humanities-sponsored study of the networks of individuals and organizations that promoted the revival of craft in the southeastern United States during the first half of the twentieth century. She is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of

"Sister Quilts from Sicily, A Pair of

Renaissance Bedcovers"

by Jonathan Holstein

Q uilter's Newsletter Magazine in its September 1993 issue had a lovely article by Susan Young, "Sister Quilts from

Sicily, A Pair of Renaissance Bedcovers" on the famous but imperfectly understood trapunto quilts thought to have been made in a Sicilian workshop of the 14th century and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Bargello

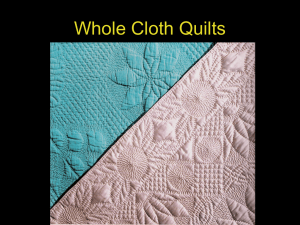

Museum, Florence. The two quilts, which display a number of familiar techniques, have long been noted as perhaps the earliest surviving Western true quilts. (For those unfamiliar with them: They are made of white linen stuffed with cotton and show scenes, in a cartoon-like narrative fashion, from the Tristan and Isolde story, extremely popular during the period. The figures are raised with trapunto and the backgrounds treated with stipple-like quilting. Wonderful calligraphy in the picture frames describes the action. There are mounted and armored knights, scenes of combat, crowded boats, a pageant of late Medieval and early Renaissance life.

Quilting was done in two different threads.)

There has been considerable confusion generally about such essential information as the origin and nature of the pieces; it was stated in the Victoria and Albert's inventory of their quilt, for instance, that it was part of the quilt now in the Bargello, and that was repeated by the Orlofskys in their

Quilts in America (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1974, pp. 3-4.) However, Pio Rajna (in a 1913 article cited at the end of thie review), Roger Loomis (in Arthurian Legends in

Medieval Art) and Averil Colby (in Quilting) state that they were a pair of quilts, and Ms. Young's careful analysis gives ample substantiation for this. (In her article she mentions the

Victoria & Albert's notation and says, "...I believe this idea is mistaken.", but does not mention that Rajna, Loomis and

Colby all thought the quilts a pair.)

Ms. Young has done an admirable job of summarizing the known documentation and interpretations, including that important 1913 analysis of the Bargello's quilt by medievalist

Pio Rajna. Its discovery in 1890 by the Countess Maddalena in a Guicciardini family villa at Usella, near Prato in Tuscany

(central Italy), and the internal evidence of the use of that family's crest (three hunting horns) on Tristan's clothes and shield, are fairly convincing evidence of its family origin. The appearance of that same crest in the Victoria and Albert quilt indicates strongly the two pieces were in some way connected. Ms. Young, drawing on Rajna's and others' historical data and her own analysis of their form, demonstrates convincingly that the quilts were a pair made for the same family. Her analysis of the current structure of the two allows her to propose (very reasonably) that the differences in size and conformation (the Bargello's quilt is asymmetrical, unlike the Victoria and Albert's, and is smaller) are almost certainly due to the Bargello quilt having been at some time altered, probably to fit on a bed smaller than the one for which it was originally made. She noted (I assume again following Rajna's lead) the three lilies on Tristan's opponent's boat and shield, a heraldic device which was associated with the Acciaiuoli family. A marriage between a member of that family and a Guicciardini was celebrated in 1395, a plausible date for the making of the two quilts, and a plausible occasion for their commissioning.

The quilts are charming in style, and would no doubt be labeled "primitive" in comparison to the high arts of the period. There was a long-established tradition of narrative textiles in Europe, perhaps the most famous being the centuries earlier Bayeaux Tapestry, a 231 foot-long linen panel embroidered by Queen Matilda and her court with a graphic account of the successful invasion of Anglo-Saxon England by her husband, William the Conqueror. That textile shows a similar pictorial treatment of episode, and also contains written "captions" or explanations of the action, etc.

I asked Ms. Young several questions. The first was, what is the evidence of the quilts' Sicilian origin? Here is her answer:

"The description of the quilts as Sicilian is supported not only by tradition, but also by the fact that Sicily was one of

Italy's famous centres of embroidery and lacework (a collection of examples is held in the Museum of Palermo). The inventory of the Victoria and Albert museum and the catalogue of the Palazzo Davanzati collection both describe the quilts as Sicilian. (The quilt had been in the Bargello, then was for a time in the Palazzo Davanzati, but since 1991 has been back in the Bargello. Ed.) Rajna bases his assertion about their origin on his detailed study of the lettering which he demonstrates to be in Sicilian dialect. In addition, the subject matter has strong links with Sicilian culture. The

Arthurian legends were known in Sicily during Norman rule and became so assimilated that it was believed Arthur had not died amongst his people but survived to live on the peaks of Mount Etna, prolonging his existence eternally by repeated acts of heroism. The Arthurian and Carolingian romances were still an important part of Sicilian culture in the 19th and 20th centuries when they provided the major part of the subject matter for the armed marionette theatre of southern Italy. The Guicciardini family originated in the

south and maintained links with that region even when based in Florence. There were other examples of Sicilian quilts in Tuscany — the 1386 inventory of the Florentine

Bartolomeo Boscoli mentions a Sicilian quilt decorated with coats-of-arms. Also, the Azzolino family have a piece of a quilt measuring 2.50 metres, estimated to have been 3.80

metres x 4.15 metres originally. It is very similar to the

Guicciardini quilts in its construction and subject matter but

Rajna believes it to have originated from Calabria rather than

Sicily because of the use of a Calabrian dialect variation.

Although apparently made in Sicily, the quilts are believed to have been commissioned by a Tuscan family. In addition to the established ownership by the Guicciardini family in

Florence, this argument is supported by the minute analysis carried out by Rajna of the version of the Tristan story which is depicted in the quilts. By comparing this version with all known texts, he shows that it is based on a Tuscan, and probably Florentine, variation."

My second question was about the filling. Ms. Young states that ". . . the filling is cotton. . . " and I found that surprising; I would have assumed that a European-made quilt of that age would have been stuffed with wool. Indeed, the Victoria and Albert had noted in a 1904 inventory that the stuffing of its Sicilian quilt was wool, and this has been stated by writers in the field for some decades (Webster, Quilts:

Their Story and How to Make Them, 1915; Kretsinger and

Hall, The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt, 1935; and Orlofsky and Orlofsky, Quilts in America, 1974, for instance). Ms.

Young's answer to my query about the stuffing was this:

"When I examined the Usella (Bargello) quilt, I believed the filling to be cotton because Rajna states that the stitching

`encloses between two fabrics, one soft and fine, the other hard and rough, a layer of cotton and cotton wick.' He also identifies the filling of the Azzolino quilt, which is visible through the many holes in its worn surface, as cotton. Lidia

Morelli also says that the filling is cotton. According to the

Victoria and Albert inventory, however, the filling of their quilt is wool. Kay Staniland, in the book Medieval Craftsmen,

Embroiderers (British Museum Press, 1991) describes the filling as 'cotton wool'."

An inquiry to the Victoria and Albert was clearly in order.

Howard Batho of the museum's Textiles and Dress Department very kindly responded to a quick query about the stuffing of its Sicilian quilt. He examined it with a colleague, and their conclusion was that it is stuffed with "unprocessed cotton wadding" rather than wool.

Thus it appears that both the Bargello's and the Victoria and Albert's quilts are filled with some form of cotton wadding, a material which must have been obtained by trade. No cotton was then grown in Europe. But there was a significant export of finished cotton textiles to Europe from the Orient and the Levant; Sicily had strong ties with the latter. The nature of the filling in the quilts would seem to imply that the cotton trade of the period included unprocessed cotton, perhaps even cotton batting. Was it being imported for making underarmor, textile armor, padded clothing and other similar applications in addition to quiltmaking?

And the third question: If the quilts were a pair, this raises the issue of bed styles. Would a pair of "twin" beds have been usual in the period? Ms. Young's response: "It was apparently common for a room to contain two great beds, for a couple as well as any children. Rajna argues that the pair were destined for the same room because the scenes in one quilt complete the story of the other."

These remarkable quilts—and any associated examples— are certainly worthy of a longer study. Let us hope Ms.

Young decides to do it.

Editors' Note

The experience of producing a journal for three years has been illuminating. Time-devouring, deadline-hounded, such endeavors are, at the small journal level, labor-intensive labors of love. Without professional journal staff, one has the broadening experience of doing every job. Working with authors, seeing ideas develop and flower into articles, has been for us particularly enjoyable.

Two factors have now encouraged us to change to an annual format: The difficulty of a biannual schedule of planning issues in which single themes can be searchingly explored, and the need to produce the journal with more economies of time and production costs. Starting in 1995, therefore, we will publish once a year, incorporating in each issue at least the same number of articles, reviews, etc., as would have appeared in two biannual volumes. That way we can plan a cluster of articles on a single theme in a given volume and have at the same time enough room to cover other unrelated, but important, topics. We will continue to publish articles and reviews of the same diversity and scope as have appeared in the Journal thus far. This change will enable us to better fulfill our mission, and we thank you in advance for your continued support of The Quilt Journal: An

International Review.

Membership Renewal

It is time to renew your membership for 1995. All 1995 membership renewals are also entitled to a onetime discounted price of $35.00 plus $3.75 shipping/handling on the collected working papers of the 1992 Louisville Celebrates the

American Quilt conferences. The following lectures, edited from the conference transcripts are included:

1. Since Kentucky: Surveying State Quilts 1981-1991.

2. Directions in Quilt Scholarship.

3. Bibliography Conference.

4. The African-American and the American Quilt.

5. Quilts and Collections - Private, Public and Corporate.

The exhibitions, conferences, lectures and gatherings which comprised the Celebration addressed issues of concern to all interested in quilts here and abroad and helped establish goals, priorities and methods for the coming decades of quilt study and appreciation. The conferences were planned to further quilt scholarship in specific areas, and to bring together scholars who might create new dialogues about quilts and help clarify scholarly aims and standards in the field.

Membership in The Quilt Project supports the publication of The Quilt Journal, the effort to establish and maintain an international quilt index, and other quiltrelated educational endeavors. Membership in 1995 will bring you The Quilt Journal twice a year. Upon joining, members will be entitled to a onetime discount of 15% on all publications, patrons and sponsors 25%. Single back issues of The Quilt Journal are available for $7.50

per copy. Visa/MasterCard accepted. Phone: 502-587-6721.

Fax: 502-897-3819. Send your checks to: The Quilt

Project/The Kentucky Quilt Project, Inc., P.O. Box 6251,

Louisville, Kentucky 40206.

Categories of Membership are:

Sponsor

Patron

$250

$100

Supporting

Sustaining

$50

$25

$15 Regular

Overseas Memberships add $5.00 per year for surface shipping.

The Kentucky Quilt Project, Inc., is a not-for-profit,

501(c)3, organization and all donations are tax deductible.