Crime And Deviance

advertisement

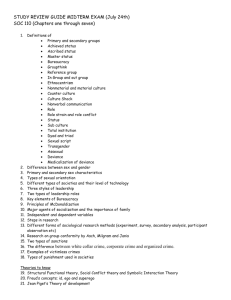

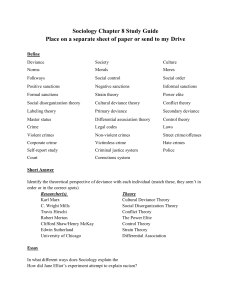

CHAPTER COMMENTARY Sociology’s treatment of crime and deviance begins with nineteenth century attempts to produce scientific explanations for crime in the form of Lombroso’s physiological theory of the individual criminal. He theorized that criminal types were a kind of evolutionary throwback (atavism) that had not adopted civilized modes of conduct and hence lived outside of normal conventions and rules. So as to demonstrate what is distinctively sociological about the accounts being put forward, both biological and psychological aetiologies of crime are considered and found to be inadequate. Students may well be challenged by the idea that the psychopath may turn to crime but equally may find a socially acceptable and legitimate outlet for those same personality and behavioural tendencies. The primary focus of this chapter is crime, but in presenting the basic concepts it quickly establishes that crime exists within the much broader category of behaviour that sociologists call deviance, defined as ‘non-conformity to a given set of norms that are accepted by a significant number of people in a community or society’ (p. 922). Crime is ‘non-conformist behaviour that breaks a law’ (p. 922). A distinction is made between criminology, which concentrates on studying crime in order to help prevent it, and the sociology of deviance, which adopts a much wider remit. Individuals at different times observe, break and create rules and those who transgress widely held social norms might, at the same time, be observing the rules of a deviant subculture. The study of deviance is always the study of power, posing the questions, whose rules are being broken and who has the power to uphold those rules? Turning to the sociological analysis of crime, the first approaches considered draw on Durkheim’s notion of anomie. Modern societies are characterized by individual freedom and choice, inevitably creating instances of non-conformity. Such instances have both adaptive and boundary maintenance functions. These ideas were developed further by American functionalism in the 1940s and 1950s, notably by Robert Merton, which is a Classic Study here. This work stresses that criminal behaviour arises amid the acceptance of socially sanctioned goals and the unequal distribution of legitimate opportunities to attain them and so may increase at a time of affluence if some are unable to meet their rising aspirations. Subcultural explanations point to the formation of delinquent subcultures among those excluded from success in the mainstream. © Polity Press 2013 This file should be used solely for the purpose of review and must not be otherwise stored, duplicated, copied or sold Crime and Deviance A further extension of Durkheim’s thought points to the positive outcomes for society in terms of both innovation and social solidarity of deviance maintained within acceptable bounds. Some theorists now argue that the boundaries have shifted to such an extent that socially disruptive levels of crime, particularly violent crime, have become normalized. Interactionist theories concentrate on how behaviours come to be defined as deviant. Labelling perspectives considers the social processes by which certain acts and actors become labelled as deviant. The same act, in different social settings, may be interpreted as ‘high spirits’ or ‘deviance’, categories normally imposed by the socially powerful upon the socially relatively powerless. The primary deviance of a transgressive act may have few consequences. However, once labelled as deviant all the actions of an individual become open to interpretation by others as deviant and individuals themselves may come to accept the label of deviant as central to their identity, a process which establishes secondary deviance. An upward spiral of deviancy amplification can be created at this point through deviancy amplification. The Classic Study of this process is Stan Cohen’s Folk Devils and Moral Panics (1972) which is given a thorough airing here. The new criminology of the 1970s saw deviance and criminality within the context of capitalist relationships of power. ‘Deviant’ behaviour from Black Power and Gay Rights activists was seen as a challenge to the political order, not as deviance. In the UK, the public panic over ‘mugging’ was reinterpreted as an ideological displacement of real problems in the sphere of production. Attention was drawn to the comparative lack of political emphasis placed upon white-collar crime compared with the petty crimes of the working class. The 1980s saw the emergence of New Left or Left Realism, which distanced itself from the more romantic strands of the new criminology with a tendency to view deviants as heroes of the working class. Victim surveys showed that crime was a real problem for the socially excluded groups in impoverished communities, those on the margins of society being at a higher risk of crime. Left realists also used the concept of relative deprivation in their explanations. This approach argues for policing strategies that build trust with all groups in the local community. Control theories see human beings as fundamentally self-interested and rational and hence willing to commit crimes if the chances of punishment are low, unless prevented by sufficiently strong personal bonds to society. Inadequate socialization means not everyone has the self-control which prevents criminal behaviour. Increasing affluence means more goods are available to be stolen and more homes are empty and vulnerable to crime during the working day. This approach is associated with Right Realism and an emphasis on crime prevention strategies focusing on making given crimes more difficult to commit, known as target hardening, along with zero tolerance policing. Together, these strategies are often called situational crime prevention – the attempt to prevent crime by focusing on the situation or environment rather than the offender and their motivations. These approaches may have the effect of simply changing the goods targeted by criminals and moving crime into less well-protected areas. The theory of ‘broken windows’ suggests that there is a direct link between the appearance of disorder in a neighbourhood and the local level of crime: metaphorically and literally, a single broken window left unrepaired acts as a beacon to offenders and creates a downward spiral of crime in an area. 184 Crime and Deviance Patterns of crime and crime statistics are notoriously difficult to interpret, as not all crimes are reported, not all reported crimes recorded and the basis on which figures are collated and presented are not stable. Using the UK as a case study, it can be said that from the 1950s to the mid-1990s there was a steady increase both in levels of recorded crime and in public anxiety about crime. Victimization surveys such as the BCS reveal higher levels of crime than officially gathered statistics but still may under-record crimes such as domestic violence, which people may be unwilling or fell unable to report. Both official figures and victimization studies recorded from the mid-1990s onward reveal a general downward trend though levels of anxiety and fear of crime do not reflect this reduction. The sociology of deviance has tended to concentrate on men, in part reflecting the lower levels of recorded criminality among women and in part the processes of labelling which are less likely to name female behaviour as deviant. This pattern can be seen as the outcome of both the processes by which a crime becomes recorded and the real social conditions of women’s lives. Women have fewer opportunities than men to engage in many criminal activities, as all aspects of their behaviour in the public sphere remain controlled and contained in a way that men’s are not. Women in some circumstances also escape being labelled as deviant or criminal by evoking the ‘gender contract’, under which they accept the definition of themselves as erratic and in need of male protection. The extent to which women’s criminal behaviour will change along with wider changes in their social position remains unclear. The impact of changing gender patterns in society has also been invoked as an explanation of apparent increases in male criminality. High levels of male unemployment produce a crisis for young men in their transition to an adult masculinity. Criminal behaviour can offer a possible source of adult masculine identity. The crimes of domestic violence, sexual harassment, sexual assault and rape are overwhelmingly crimes committed by men against women. Only a small proportion of rapes come to the attention of the authorities, although the number has increased as police and courts have been made more aware of, and more sensitive to, these issues. Rape is not about sexual desire but about violence, power and control in a sexualized way. All women are affected by rape as fear of it limits freedom on the streets and can even create anxiety when home alone. Just as all women are expected to modify their behaviour, or risk being seen as ‘asking for it’, so too are gay men and lesbians who are publicly open about their sexuality. Youth crime, as Cohen and others have argued, is an area which crystallizes wider social concerns and the introduction of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (ASBOs) and similar initiatives can be seen to criminalize low-level deviance. The chapter now turns to consider middle-class crimes, which run counter to popular perceptions of both crime and criminality. White-collar crime covers a range of illegal activities open to those with professional occupations, notably in the financial sector, and refers to offences which are not sanctioned by companies and may harm them, such as fraud and embezzlement. Corporate crime covers all of those harmful activities by corporations in pursuit of their own interests such as pollution, mislabelling and violations of health and safety legislation. In these cases, the gap between the perpetrator and the victim of crime is large, but these are not victimless crimes and the victims are often the most vulnerable in society. 185 Crime and Deviance The next section of the chapter turns to consider responses to crime. The UK and USA are countries particularly wedded to custodial sentencing in response to criminal behaviour. High rates of recidivism call into question its effectiveness as a tool for either rehabilitation or deterrence and in part account for recent interest in restorative justice approaches. Recent policy has seen a move towards restorative justice and community punishments though sociologists argue that we should not see these as simple solutions to the prevention of crime and deviance. Restorative justice seeks to raise awareness among offenders of the impact of their crimes on victims. A further aspect of economic and political globalization is the international spread of organized crime. Such crime represents multimillion-dollar international trade, often linked with the illegal narcotics industry and masked by legitimate business activity based in areas of low risk for the criminals such as the former Soviet Union. Cybercrime has grown along with the Internet, and operates outside geographical constraints, posing particular challenges for international law and law enforcement agencies. Wall’s distinction between first, second and third (or ‘true) cybercrimes is adopted to show how some crimes simply make use of the new ICTs whilst others only become possible with its rise. TEACHING TOPICS 1. Learning and labelling Much criminal behaviour, whilst breaking the rules of society, is behaviour which obeys the rules of the subculture within which it is located. Such behaviour is learned through processes of socialization, and the acceptance of a deviant label may promote the solidarity of the subcultural group. This topic builds upon the section ‘Explaining crime and deviance: sociological theories’. 2. Victims and perpetrators Dimensions of social inequality are linked in a variety of ways to crime and criminality. The section on ‘Conflict theories and the new criminology’ explores some class dimensions, while the section ‘Victims and perpetrators of crime’ also touches on class but explores more thoroughly issues of gender and sexuality. 3. Young people and prison This theme links together two areas raised in the chapter: ‘Youth and crime’ and ‘Prisons and punishment’ and builds upon Using Your Sociological Imagination 21.1’s example of the death in custody of Adam Rickwood in the UK context. ACTIVITIES Activity 1: Learning and labelling Using marijuana is illegal in Britain. For many people, though, the use of marijuana is part of their everyday life. These people are acting criminally and would be seen by many as ‘deviants’, but within their own subcultures their behaviour is seen as normal and is governed by taken-for-granted rules of interaction in much the same way as other 186 Crime and Deviance aspects of social life. Like other aspects of social life using marihuana is learned behaviour which the individual is taught through processes of socialization. Howard Becker’s classic Outsiders, details the stages in becoming a marijuana user. He identifies three key stages in the transition from being someone who has reached the point of being willing to try marijuana to becoming a user of marijuana for pleasure. The stages are: learning the technique, learning to perceive the effects and learning to enjoy the effects. This study was conducted among musicians in the United States in the early 1960s. At that time smoking marijuana was an important element in the subculture of jazz musicians and was woven into the subcultural whole through the use of language and the rituals of usage. This extract is taken from the section in Becker’s book, ‘Learning to Enjoy the Effects’, and deals with the role of experienced marijuana users in teaching novices to redefine their sometimes unpleasant and frightening first experiences of marijuana use into something pleasurable: An experienced user describes how he handles newcomers to marijuana use: Well, they get pretty high sometimes. The average person isn’t ready for that, and it is a little frightening to them sometimes. I mean, they’ve been high on lush [alcohol], and they don’t know what's happening to them. Because they think they’re going to keep going up, up, up till they lose their minds or begin doing weird things or something. You have to like reassure them, explain to them that they’re not really flipping or anything, that they’re gonna be all right. You have to just talk them out of being afraid. Keep talking to them, reassuring, telling them it's all right. And come on with your own story, you know: ‘The same thing happened to me. You’ll get to like that after a while.’ Keep coming on like that; pretty soon you talk them out of being scared. And besides they see you doing it and nothing horrible is happening to you, so that gives them more confidence. The more experienced user may also teach the novice to regulate the amount he smokes more carefully, so as to avoid any severely uncomfortable symptoms while retaining the pleasant ones. Finally, he teaches the new user that he can ‘get to like it after a while.’ He teaches him to regard those ambiguous experiences formerly defined as unpleasant as enjoyable […] In short, what was once frightening and distasteful becomes, after a taste for it is built up, pleasant, desired and sought after. Enjoyment is introduced by the favorable definition of the experience that one acquires from others. Without this, use will not continue, for marijuana will not be for the user an object he can use for pleasure. (Howard Becker, Outsiders, New York: Free Press, 1963, pp. 55–6) 1. How is this process an induction into both deviance and conformity? Activity 2: Victims and perpetrators Until the 1950s, male homosexuality was a criminal act in the UK. The forces of law and order were charged to police and punish the act. Until the 1970s, homosexuality was seen as an illness to be treated. In the fairly recent past male homosexuality has been 187 Crime and Deviance variously seen as a sickness, a deviance and an evil. Today, some individuals and groups retain these views, even though homosexuality is, no longer a crime. The question of crime and homosexuality now focuses on those who would express their dislike and disapproval of homosexuality through violent means. The Criminal Justice Act, 2003, permits judges to increase sentences in the context of ‘hate crimes’ including homophobic attacks. Read the subsection ‘Crimes against homosexuals’ (pages 946-7), which outlines a paper by Diane Richardson and Hazel May (1999). Now read this extract from that paper: Consideration of how we understand and explain violence differently in relation to who the victim is, rather than the circumstances in which the violence occurs, raises the question of the social recognition and worth accorded certain individuals or social groups and, related to this, the degree to which they are considered to have ‘lives worth living’ … The focus on lesbians and gay men is extremely useful in highlighting how interpretations of violence are mediated through notions of culpability and victimisation. As a marginalised and stigmatised group within society, lesbians and gay men are unlikely to be construed as ‘innocent’ victims. On the contrary, the idea of the ‘homosexual’ as dangerous, a threat both to individuals they have contact with, especially children, and to national security and social order has a long history … Analysis of the meanings attributed to violence towards lesbians and gay men, therefore, helps to make explicit the normative processes by which we define someone as an ‘undeserving’ or ‘deserving’ victim … … The idea that the public existence of ‘homosexuals’ represents some form of provocation, which renders violence and harassment intelligible, is evident in institutional as well as informal assessments of public violence. This is supported by the literature on homophobic violence … which draws attention to the failure of the police to acknowledge the significance of recording ‘sexual orientation’ among the reasons which motivate attackers to abuse and kill, and the reluctance of the courts to impose harsh sentences on the perpetrators of such crimes. (Diane Richardson and Hazel May, ‘Deserving victims?: sexual status and the social construction of violence’, Sociological Review, 1999, pp. 308–31) 1. What other groups are sometimes seen to be ‘asking for it’? 2. In what ways is this analysis of the position of gay men and lesbians as victims of crime similar to the analysis of ethnic minority groups as victims of crime? 3. Could there be a link between anti-gay crime and the ‘crisis of masculinity’? Activity 3: Young people and prison The section ‘Youth and crime’ points to the ways in which public fears about a general social and moral breakdown become focused upon the question of youth crime. These fears far outstrip the reality of youth crime and often focus upon deviant rather than strictly criminal acts. The ‘law and order’ emphasis upon drug use and the use of AntiSocial Behaviour Orders (ASBOs) can have the effect of criminalizing behaviour which in other ways can be seen as a normal part of growing up. Read that section now. 188 Crime and Deviance The section ‘Prisons and punishment’ points to the tensions which create a situation where the prison population in the UK is growing and is significantly higher as a proportion of the population than other European countries, despite evidence which strongly suggests that prison is not a rehabilitative or deterrent force and may, in fact, contribute to hardening the criminality of inmates. Read that section now and pay particular attention to the case of Adam Rickwood (pages 956-7). Barry Goldson conducted research over a 12-month period in 2001 and 2002 into young people (he prefers the term ‘children’) held in locked institutions. Locked institutions take two different forms: Secure Units, run by local authorities and the Department of Health, where young people deemed to be ‘at risk’ can be placed; and Young Offender Institutions, managed by the prison service and the Home Office, which hold young people charged or convicted with criminal offences. In fact, the backgrounds and circumstances of the young people in these two types of institution share much in common. The extract below refers specifically to Young Offender Institutions. Some children interviewed for the study reported negative treatment from the prison staff. Even if prison staff were willing to meet the inmates’ needs, Goldson found that understaffing meant that in practice staff were unable to give them appropriate care. For Goldson, the consequences of such neglect for children are apparent: It hurts all the time. All you do is miss your family and you can’t hack it sometimes. I wouldn’t send kids to a place like this. (Boy, 16 years) I felt very lonely and that, very lonely really. You are on your own and there is no one to talk to. All you can do is think and it really winds you up. I had no one to speak to and it all built-up and I started thinking that I can’t take anymore. (Boy, 16 years) Worse still, young offender institutions are not just neglectful, they are sites of concentrated bullying in all its forms – physical assault, sexual assault, verbal abuse, racist abuse ad assault, intimidation, extortion and theft. Prison staff explain: It comes in waves, it depends who’s on the wing. You get kids bullying each other, you get staff bullying kids and you get staff bullying staff. … Outside the kids can get status in lots of ways. In here status is measured in different ways: fear and respect become very confused. (Female prison officer) I think that it occurs all the time in different ways. … Especially with verbal bullying, or just an attitude which is a form of bullying, people don’t always see it, particularly staff I would say. They call it discipline but it’s really bullying, it’s an abuse of power. (Male prison nurse) In other settings such behaviour would be called child abuse. (Barry Goldson, ‘Victims or threats? Children, care and control’, in Janet Fink (ed.), Care: Personal Lives and Social Policy, Bristol: The Policy Press in association with the Open University, 2004, pp. 103–4) 189 Crime and Deviance 1. In Sociology the term ‘youth’ is used; in the commentary here, ‘young people’; and by Goldson himself, ‘children’. Does the choice of term affect the way you think about the situation of these 15- and 16-year olds? How might labelling theorists interpret the choice of language? 2. If prison does not work as a mechanism for rehabilitation or deterrence, what other social purposes may it serve, particularly with regard to young people? 3. What are the similarities and differences between the example of Adam Rickwood and the young people in the Goldson extract? REFLECTION & DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Learning and labelling What workplace crimes are accepted as normal behaviour? How might being labelled as deviant affect the interpretation of an individual’s actions? How can an activity once seen as deviant become a societal norm? How does differential association affect both the opportunities to become deviant and the likelihood of being labelled as such? Victims and perpetrators Why do women and men commit different kinds of crime? Will women have gained equality when they are as criminal as men? Why might the rate of sexual offences be underreported? Should the police collect statistics which identify the sexuality of the victim? Young people and prison What might a young person learn during a custodial sentence? Could Young Offender Institutions be made more effective as a mechanism of rehabilitation? What alternative non-custodial sentence could be used with young people? ESSAY QUESTIONS 1. Both actual crime and crime statistics are the products of social inequalities, albeit in different ways. Discuss. 2. In what ways are we all rule-breakers and rule-creators? 3. Why does society find it easier to accept women as the victims rather than the perpetrators of violent crime, and members of ethnic minority groups as perpetrators rather than victims? MAKING CONNECTIONS Learning and labelling This topic draws together interactionist concerns, discussed in Chapter 8, and issues of socialization through the life course from Chapter 9. Labelling and deviance feature 190 Crime and Deviance again in the context of anti-school sub-cultures in Chapter 20 and are clearly applicable to the social construction of disability from Chapter 11 and age-based categories from Chapter 9. Victims and perpetrators This topic aims to open up the relationship between the social construction of the deviant actors ‘perpetrator’ and ‘victim’ and broader social constructions of gender, sexualities and ethnic identities: Chapters 15 and 16 are therefore particularly useful. Young people and prison This topic asks students to make links between arguments about youth crime and prison and draw upon both functionalism and labelling theory in their answers. It provides a good example of the social construction of ‘youth’ and can be linked to chapter 9. More subtle links can also be made to theories of childhood development from the same chapter. Another route would be to explore functionalist accounts of deviance linked to the discussion of Durkheim in Chapter 1 as well as Foucault’s accounts of modern organization and surveillance in Chapters 3 and 19. SAMPLE SESSION Learning and labelling Aims To show that deviance is not a property of behaviour but of the social meaning of behaviour To show that deviant behaviour follows group norms Outcome: By the end of the session students will be able to: 1. Explain the terms ‘differential association’ and ‘labelling theory’ 2. Give examples of how deviant behaviour is learned and follows social rules. 3. Summarize and organise information from a number of sources Preparatory tasks Read the section ‘Explaining crime and deviance: sociological theories’. Read the extract provided from Becker. Think about any examples of subcultural behaviour which you have been similarly socialized into. Classroom tasks 1. Tutor introduces exercises and explains assessment task. (5 minutes) 2. Divide the class into small groups and issue each with flip-chart paper and marker pens. Each group should elect both a scribe and a reporter to feed back on the group’s behalf: (a) The drug users Becker discussed have their own vocabulary: write down any terms from contemporary youth culture that these 1960s deviants would have trouble understanding? (b) Other than illegal drugs, are there any aspects of youth culture that you have to ‘learn to like’? (a + b = 15 minutes) 3. Groups feedback and flip-charts are placed on the wall for the rest of the session. (5 minutes) 191 Crime and Deviance 4. Tutor poses the question ‘When does drinking alcohol become deviant?’ In the same groups students are encouraged to discuss the question, take a pen each and write down with minimal editing any ideas as they come to them. (10 minutes) 5. The flip-charts are displayed on the wall with no formal feedback. For the rest of the session students have the opportunity to wander round and read the sheets taking any notes as they go. Assessment task Write a report which summarizes the answers from all groups to the questions above. 192