E m e rging Te x t u res: a brief history of twist

advertisement

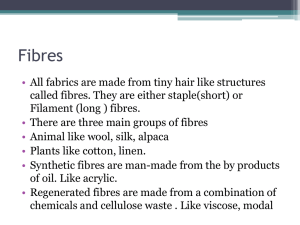

Emerging Textures: a brief history of twist Ann Richards Yarn twist has always been an important element in textile design, as it has such a powerful influence on the appearance, handle and functional properties of fabrics. Firmly twisted yarns can create very hardwearing fabrics and this must have been a serious, practical issue since the earliest times. However, yarn twist can also be a major element in decorative design; such techniques have a surprisingly long history and continue to be inspiring today. Early Decorative Uses of Yarn Twist Yarns can be twisted in two different directions, Z and S, and these reflect light differently. Stripes of the different twists can be used in warp, weft or both to create ‘shadow’ stripes and checks, and such techniques were used as far back as the Bronze Age (1400 – 1200 BCE). When combined with high levels of twist, such yarns can also create textured effects, which emerge naturally from the interplay of yarn twist and weave structure. Fabrics exploiting such textures have been produced for thousands of years, particularly in ancient China: a fragment of silk from the Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1050 BCE) has an uneven surface created by tightly twisted warps and wefts. Another piece, about 2400 years old, already shows the alternation of Z and S twists that has become the classic crêpe construction, still used today, which gives an overall crinkled texture. The ancient Egyptians may also have been aware of the possibilities of yarn twist for creating textured effects; some of the textiles that have been excavated include yarns that are very highly twisted. The Egyptologist Rosalind Janssen (formerly Hall) has described a Fifth Dynasty (2498 – 2345 BCE) dress which revealed, during conservation, that it might have been designed to pleat spontaneously. She also cites wall paintings of the A banquet scene from Nebamun’s tomb shows guests wearing clothes with rippled pleats. Photo: Alan Costall 8 Journal for Weavers, Spinners and Dyers 247, Autumn 2013 Eighteenth Dynasty (1550 – 1290 BCE), which she believes may represent ‘natural’ pleating. For example, the beautiful paintings from Nebamun’s tomb, now at the British Museum, show people wearing garments with rippled pleats, very different from the usual representations of pleated garments in Egyptian paintings. Unlike the Chinese, the Egyptians used only one direction of yarn twist, S, for their woven fabrics. If high-twist1 yarns were used with an open sett, this would have produced an effect of irregular pleating (crepon) rather than the overall crinkled texture of crêpe. From such early beginnings, the fine-scale texture of the crêpe effect and the stronger texture of crepon have continued in use over many centuries; the elasticity of such fabrics have made them extremely suitable for traditional garments of a very simple cut. Although their popularity has fluctuated over the last century as fashions in clothing have varied, crêpe and crepon remain classic fashion fabrics, still used when fluid and flexible effects are required. Twentieth Century to Today Towards the end of the twentieth century, new developments took place in the design of naturally textured textiles. Two different groups of people began to experiment with high-twist yarns and, in so doing, extended the range of design to include bolder effects than those of the traditional crêpe and crepon. Working on an industrial scale, the Japanese designer Junichi Arai began to use high-twist yarns in the 1970s and 1980s, combining them with computer-controlled Jacquard weaving to produce boldly patterned and textured fabrics for fashion designers, such as Issey Miyake. In 1984 Arai, who has been referred to as the best ‘textile planner’ in the world, co-founded the NUNO Corporation with another highly imaginative Japanese designer, Reiko Sudo. NUNO (the word means ‘fabric’ in Japanese) has become famous for innovative textile design and a willingness to mix simple hand techniques with state-ofthe-art technology in pursuit of an idea. NUNO’s work has been beautifully recorded in a series of books, and their website (www.nuno.com) also provides many illustrations, together with a history of the company. At about the same time, a new interest in naturally textured textiles was also developing within the handweaving community. Anne Blinks drew attention to the disturbances produced by overtwisted yarns, showing her samples of textured fabrics to interested handweavers. She also coined the term ‘collapse’ (see In Search of Collapse by Lillian Elliott), which has since become widely used, especially as a way to refer to relatively large-scale effects, as compared with the very fine-scale texture of traditional crêpes. Sharon Alderman, Lillian Elliot and Mary Frame followed up these ideas and their intriguing and informative articles, written in the mid 1980s, brought ideas about high-twist yarns to a wide audience of handspinners and weavers. I was a student at the Surrey Institute of Art and Design (Farnham) at around the time these articles were published and they strongly influenced the whole direction of my work. Natural Textures Come of Age Many other spinners and weavers have since experimented with high-twist yarns, with Lotte Dalgaard, Anne Field and Anna Champeney being particularly active in exploring the possibilities. So, from the context of a long history, a renewed interest in using ‘natural’ textures as a major design element has gradually emerged over the past thirty years. Many handweavers have now become aware of such textural effects, usually under the catch-all term of ‘collapse’ weave, but although this provides a convenient shorthand it can convey a misleading impression of uniformity in a field of design that is, in reality, very diverse. The time seems ripe to set these developments in context, by digging deeper into the basic principles involved. A closer look at yarn twist shows how an apparently simple mechanism can produce a wide variety of different textures. The precise form of these textures varies depending on the fibre, amount of yarn twist and sett. These twist interactions can also create textural variations across the fabric, if broad stripes of Z and S are used in the warp or weft, or both. These intersect to give stripes or blocks of sametwist and opposite-twist textures. The undulating texture causes more fabric contraction than the tracking effect, so interesting curves can emerge from the blocks of different textures, or entire pieces of cloth can be shaped by such variations of texture. Stress and the Crêping Reaction Although adding twist gives strength to yarns, it also imposes a stress and this has the effect of making yarns unbalanced, so that they tend to crinkle and spiral in an attempt to escape their stressful situation. Though restrained by weave structure, these movements can create texture within a finished cloth when it is wetted out. The fibres absorb water and swell, imposing an additional stress that triggers the spiralling reaction, and the textures that are produced are generally retained as the fabric dries. Although this sounds simple enough, a surprisingly wide range of textures can be produced, as the inherent properties of the fibres, the amount and direction of yarn twist, the weave structure and sett, all come to play their part in the process. To start with, the various natural fibres behave differently in their responses to stress. Wool, with its wide range of qualities in different breeds of sheep, is in itself a varied material. Different spinning methods also contribute – soft woollen yarns, made from fine, short, randomly arranged fibres, react differently to stiffer worsted yarns, made from thicker longwools and with good fibre alignment. Soft woollen yarns tend to shrink and crinkle tightly, while stiffer worsted yarns create larger spirals and consequently larger scale textures. Structure and sett also make an impact, so the interplay of many apparently simple elements produces an emergent complexity that can sometimes be hard to anticipate. A small change may cause surprising repercussions throughout the fabric, a textile equivalent of the ‘butterfly effect’ familiar from the scientific fields of chaos and complexity. This sensitivity to subtle variations makes for an exceptionally interesting area of textile design with plenty of scope for experiment. Twist Direction in Plain Weave Even with plain weave, the interactions of unbalanced S and Z yarns offer various possibilities for design. When the direction of twist is the same for warp and weft (Z x Z or S x S), a characteristic ‘tracking’ pattern is produced, but when opposite twists are used in warp and weft (Z x S), a very different, larger-scale pattern will appear, forming distinct undulations in the fabric surface. A sample of plain weave where stripes of Z and S yarns have been used in both warp and weft. Curves emerge from the chequerboard of same-twist and oppositetwist textures Photos: Ann Richards These effects arise from using high-twist yarns in both warp and weft, but many interesting designs can be produced when hightwist yarns are combined with lower-twist or balanced yarns – these can usefully be thought of as ‘active’ and ‘passive’ yarns. This may simply be a matter of using a relatively easy-to-handle ‘passive’ yarn in the warp, while the more excitable ‘active’ yarn is used for the weft, to create crepon or crêpe effects. But ‘active’ and ‘passive’ yarns may also be combined in the weft to produce seersucker effects or to create frilled borders for accessories such as scarves or bracelets. Journal for Weavers, Spinners and Dyers 247, Autumn 2013 9 Both high-twist and balanced yarns are used in a structure that combines plain weave and floats to create the crisp pleating in this neckpiece Double or multiple layer cloths also offer wide possibilities for design. Layers with different shrinkage potential can be combined and interwoven in various ways, giving an immense range of textured fabrics. Combinations of double and single cloth also offer great scope for both texture and pattern. Once again, these fabrics often have a very different character from the random textures of ‘collapse’ effects in plain weave. Differential shrinkage between layers creates a textured surface in this double/single cloth in wool and silk Photos: Ann Richards Wool and silk crêpe yarns are played off against stiff metal yarns to create these crepon bracelets with frilled edges Twist and Weave Structure High-twist yarns in plain weave often give a rather randomly textured effect and, although this is obviously part of the charm of these techniques, introducing more complex weaves will open up additional possibilities. The interplay of high-twist yarns with various weave structures allows the creation of more carefully ordered textures. In particular, structures that combine firmly woven areas (which constrain the yarns) together with localised floats (allowing shrinkage) have great potential for precisely organised effects such as accordion pleats. Such crisply controlled textures can be very different from the random crinkling that many weavers have come to associate with ‘collapse’ fabrics. 10 Journal for Weavers, Spinners and Dyers 247, Autumn 2013 It is also possible to vary the weave structure across or along the cloth, changing the capacity for shrinkage, so that rectangular pieces of fabric will change shape during wet finishing. Such techniques can be used to give flared edges to scarves or shawls and also to create ‘loom-to-body’ clothing that requires minimal cutting and sewing. allowance needs to be made for the very different character of these new yarns. Even metal yarns, which one might expect to be very stable, can sometimes mimic the behaviour of high-twist yarns, creating boldly textured fabrics; Wendy Morris has made a detailed study of these intriguing effects. Traditional high-twist yarns and the new synthetics and metallics were once very difficult to obtain, but they have recently become much more readily available to handweavers, through the efforts of the Danish Yarn Purchasing Association (www.yarn.dk) and adventurous suppliers such as Handweavers Studio in the UK, and Habu in the USA. So now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, we find ourselves in the happy situation of having the necessary materials much more easily available than ever before, while techniques that originated in the distant past remain as inspirational as ever. Long may exuberant textures continue to emerge! 1 High-twist in this context is referring to unbalanced yarns containing residual energy, whether plied or not. Bibliography ‘Doublecloth Loop’ scarf. Along the length of the scarf, plain weave is used in both layers to create crepon textures. The border combines single and double cloth to create a flared edge Photo: Ann Richards Twist and Texture for the Future These few examples can do no more than hint at the huge range of effects that can be created using high-twist yarns, combined with the simple process of soaking the finished fabric in water; the possibilities truly are endless. Further options open up through the use of additional techniques, such as heavy milling or woven shibori, since these can be combined with high-twist yarns to develop special effects. Some of the traditional techniques and structures that have been evolved to exploit yarn twist can also be very effectively used with the many synthetic shrinking and elastic yarns that have been produced over the past century, though some Alderman, Sharon (1985) Tracking the Mystery of the Crinkling Cloth, Handwoven, Sept/Oct 1985: pp. 31 – 33. Champeney, Anna (2009) Fun with Floats: Crinkle Scarves with Classic Overshot, Journal WSD, 232: pp. 21 – 23. Dalgaard, Lotte (2012): Magical Materials to Weave, North Pomfret, Vermont: Trafalgar. Elliott, Lillian (1983) In Search of Collapse, in Rogers, Nora and Stanley, Martha, In Celebration of the Curious Mind, Loveland, CO: Interweave Press. Field, Anne (2008): Collapse Weave, London: A&C Black. Frame, Mary (1986) Ringlets and Waves: Undulations from Overtwist, Spin-Off, December 1986: pp. 28 – 33. Frame, Mary (1987) Are You Ready To Collapse?, Spin-Off, March 1987: pp. 41 – 46. Hall, Rosalind (1986): Egyptian Textiles, Aylesbury: Shire Publications. Hall, Rosalind (1986) ‘Crimpled’ Garments: A Mode of Dinner Dress, Discussions in Egyptology, 5: pp. 37 – 45. Morris, Wendy (2012) All that Glisters – Collapse Effects with Metallic Yarns and Wires, Journal WSD, 244: pp. 6 – 9. NUNO Corporation (1998) Fuwa Fuwa, Japan: NUNO Corporation. NUNO Corporation (1998) Boro Boro, Japan: NUNO Corporation. Richards, Ann (2012) Weaving Textiles That Shape Themselves, Ramsbury: Crowood Press. Richards, Ann (in press) Could Ancient Egyptian Textiles Have Pleated Themselves? Experiment and Experience: Ancient Egypt in the Present, Swansea: Swansea University. Sutton, Ann (1992): The Textiles of Junichi Arai, Hon RDI, Journal WSD 161: pp. 14 – 15. About the author Ann Richards trained and worked as a biologist, but then went on to study weaving at the Surrey Institute of Art & Design, Farnham, where she later also taught. She works mainly with high-twist yarns, creating strongly textured fabrics with elastic properties. Influences on her textiles include origami, biomimetics and archaeology. Journal for Weavers, Spinners and Dyers 247, Autumn 2013 11