The impact of significant others' actual appraisals on children's self

advertisement

European Joumal of Psychology of Education

2009. Vol. XXIV. n"2. 247-262

€'2009.1.S.P,A.

The impact of significant others' actual appraisals

on children's self-perceptions:

What about Cooley's assumption for children?

Cécile Nurra

Pascal Pansu

University of Grenoble 2, France

The aim of this paper was to study the construction of children's

self-perception relying on Cooley 's hypothesis. More precisely, we

were interested in the mediation effect of signiftcant others' actual

appraisal on self-perception by the perception of others' actual

apprai.sal (i.e.. reflected appraLuil). First, we argued that this mediation

effect would occur in the domains where children have feedback from

signiftcant others (here teacher or parents). Second, we took into

account two measures of reßected appraisal: reflected appraisal

assessed in a cla.ssic fashion and appraisal .social support assessed with

Harter 's seale (1985b). We argued that reflected appraisal assessed in

a classic fashion would be a better mediator of the effect of actual

appraisal on self-perception by reflected apprai.sal in comparison to

appraisal .social .mpport. In order to test these hypotheses, we conducted

a study with 126 children (age 8-9). ¡06 parents and six teachers. The

results, taken as a whole, support these hypotheses.

The aim of this paper was to expand our understanding of the construction of children's

evaluations of themselves. Two major kinds of detemiinants have been found in literature dealing

with the construction of self-evaluations (e,g,, Leary, 2006). The first one focuses on the

intrapersonal determinants. For instance, global evaluation results from the integration of specific

self-evaluations (Harter, 1999), The seeond one focuses on interpersonal déterminants. Here

scholars study the impact others have on self-evaluation (Markus & Cross. 1990). This impact can

be studied in different ways as. for example, the impact of others" expectations on behaviors (e,g.,

Jussim, 1986) or how competent is the person with whom one compares him/herself (e.g,. Wood

& Wilson. 2003), Another way others have an infiuence on self-evaluations is through their

judgments and feedback (Markus & Wurf. 1987), The impact of other's judgments and feedback

has been mostly studied relying on Cooley's (1902) framework which has been particularly

relevant when dealing with children's self-pereeption (Hart. Atkins, & Tursi, 2006; Harter. 1999).

The goal of the current paper was to provide additional support to Cooley's ( 1902) hypothesis.

Authors want to thanks Dominique Müller. Mona F.l-Shamaa and two anonymous reviewers fnr ihcir helpful

comments.

248

C. NURRA & P. PANSU

According to Cooley ( 1902), significant others' Judgments and feedback arc involved in

the construction of self-perceptions. These significant others would be like a looking glass

self, a mirror into which we can see how we are. This author argues that "the thing that moves

us to pride and shame is not the merely mechanical reflection of ourselves but an imputed

sentiment, the imagined effect of this reflection upon another's mind" (Cooley, 1902, p. 184).

When signifieant others make a judgment about us (i.e.. significant others' actual appraisal),

we perceive this judgment (i.e.„ reflected appraisal) and this perception influences how we

think about ourselves {i.e., self-perception). In other words, we evaluate ourselves as we think

others evaluate us.

Following this long-standing tradition of research., results support this hypothesis when

the effect of actual appraisal on self-perception is mediated by reflected appraisal {Felson,

1989). Framing Cooley's (1902) hypothesis in terms of mediation suggests that three

relationships must be demonstrated (Felson, 1985; Shrauger & Schoeneman, 1979): first, a

relationship between actual-appraisal and self-perception, second, a relationship between

actual appraisal and reflected appraisal and third, a relationship between reflected appraisal

and self-perception. Furthermore, reflected appraisal should account tor the relationship

between aetual appraisal and self-pereeption. In other words, the strength of this relationship

should be decreased when reflected appraisal is statistically held constant. As we shall see, a

full support for these different conditions has not been found in related literature. In this paper,

we argue, however, that these different conditions ean be mei with children as long as we take

into account difterent domains of self-perceptions and signiflcant others, and we choose a

suitable measure tbr reflected appraisal.

Studies that focus on the actual appraisal effect on children's self-pereeptions lead to

mixed conclusions. The important Shrauger and Schoeneman (1979) literature review shows

that there is no clear evidence concerning the effect of significant other's actual appraisal on

self-perceptions. However, when different domains and significant others are taken into

account, several studies reported that the actual appraisal of parents, teaeher and peers actually

affected self-perception more clearly. For example. Cole (1991) showed that peers' and

teacher's actual appraisals have an effect on children's self-perceptions. Importantly, Cole

(199!) showed that this effect depends on the domains under consideration; peers" actual

appraisal predicted change in self-perception in social and academic domains, whereas

teacher's actual appraisal predicted change in athletic self-pereeption. Results by Cole,

Jacquez, and Maschman (2001) also supported this view. Their results showed ihal teacher's,

parents' and peers' actual perception were correlated with self-perception in the important

domains for ehildren - although this correlation was only weak for social acceptance and

physical appearance (see also Cole, Maxwell, i& Martin. 1997). Research conccming more

specifically the academic domain showed that teacher's actual appraisal had an effect on

children's academic self-perception (Gesl. DoETiitrovich. & Welsh, 2005; Herbert & Stipek,

2005). but also on social and behavioral conduct self-perception (Bressoux & Pansu. 2003).

As far as parents are concerned, Felson (1989) showed that parents' actual appraisal has an

effect on children's academic self-perception. Therefore, it seems that the relationship

between actual appraisal and self-perception can be found, but only within particular

combinations of domains and significant others.

If, as Cooley (1902) suggested, reflected appraisal is the mediator of the aetual appraisal

effect on self-perception, we should observe both a relationship between actual appraisal and

reflected appraisal, and a relationship between reflected appraisal and self-pereeption. Studies

testing the relationship between aetual appraisal and reflected appraisal reported only weak

evidence (Cook & Douglas. 1998; Felson, 1985). On the contrary, studies testing the

relationship between reflected appraisal and self-perception reported clearer evidence (e.g.,

Felson, 1989), Studies also reported that the effect of actual appraisal on self-perception is not

mediated by reflected appraisal. For example. Felson (1989) showed that self-perception was

influenced by both parents' actual appraisal and refleeted appraisal. Refteeted appraisal,

however, did not mediate the effect of actual appraisal on self-perception. In the same fashion,

Hergovlch. Sirsch, and Felinger (2002) showed more recently a relationship between teacher's

OTHERS* APPRAISAL AND CHILDREN'S SELF-PERCEPTION

249

and parents' aetual appraisals in various domains of children's self-perceptions. But again.

they concluded that there was no mediation because this relationship was shown to be

significant when retlected appraisals were controlled. These results suggest that the effecis of

actual appraisal and reflected appraisal are independent (Felson, 1989). Authors like Felson

(1989) even argue that the mediation was not obtained because the relationship between

reflected appraisal and self-perception could be opposite of Cooley's (1902) hypothesis: selfperception would influence reflected appraisal. Such an inverse relationship could be

explained by the fact that when we evaluate what others think about us, we use private

information that others do not have (Chambers. Epiey. Savitsky. & WindschitI, 200K). Hence,

we would often attribute to other people the perception we have about ourselves, what Felson

(1989) referred lo as a projection effect.

What emerges from these results is a weak support of Cooley's hypothesis: whereas the

relationship between reflected appraisal and self-perception is high, the relationship between

actual appraisal and reflected appraisal is weak or absent (e.g., Felson. 1989). We would argue,

however, that the mediation implied in Cooley's hypothesis has to be studied with at least two

considerations in mind. The first is the specificity of domains and significant others. The second

has to do with the measure we rely on to test the meditational role of reflected appraisal.

Specificity of domains and signifícant others

Results we presented above showed how the relationship between actual appraisal and

self-perception depends on the domains and the significant others taken into account (e.g.,

Cole et al., 2001). It could be suggested that ihis is so because significant others do not give

feedback in all domains (Boivin. Vitaro. & Gagnon. 1992; Funder & Colvin. 1997). Thus, the

relationship could be observed only when children received feedback from significant others.

Applying a similar reasoning. Jussim. Soffin. Brown, Ley. and Kohlhepp (1992) argued that

reflected appraisal could have an effect on self-perception when we have infonnation about

how others see us. In contrast, these authors propose that the reverse relationship (i.e.,

projection effect) should be observed when we do not have enough information. Some results

support this idea. For instance. Malloy. Albright, Kenny, and Winquisi (1997) showed that the

relationship between actual appraisal and reflected appraisal is getting larger as others are

closer to the target. Their results revealed that this relationship was larger for family members

as eompared with friends and was also larger for friends as compared with colleagues. Finally,

this same reasoning could be applied to the mediation through reflected appraisal: this

mediation should be lound when participants have enough information on how they are

perceived. In line with this idea. Bois, Sarrazin. Brustad. Chanal. and Trouilloud (2005)

showed that the effect of parents" physical abilities aetual appraisal on physical ability selfperception was mediated by reflected appraisal. Even though these results are in line with the

"importance of feedback" reasoning, only one domain was investigated in this study.

Extending past research, we postulated that the different relationships implied by

Cooley's (1902) hypothesis should be found when children receive feedback from the

significant others. To test this hypothesis, we took into account, simultaneously, five domains

and two significant others, Hence, we selected the five domains considered as important for

children: academic competence, behavioral conduct, social acceptance, physical ability, and

physical appearance (Harter. 1985a). As for significant others, we selected the two most

significant others in the construction of children's self-perceptions in middle childhood:

teaeher and parents (Sarason. Pierce. Bannerman, & Sarason, 1993).

Relying on these different domains and signifieant others we tested the following

hypotheses. First, as teachers provide feedback particularly in académie and behavioral

conduct domains, we predicted a mediation only for these two domains. Second, as parents

give feedback to their children on all the important domains of their life, we predicted a

mediation for all the domains.

250

C. NURRA & P. PANSU

Refiected appraisal measures

As mentioned earlier, we have to pay ¡itlcnlion to the measure we use. In fact, the

variability in the measure used to study Cooley's hypothesis (1902) also contributed to ihe

lack of consensus on the question (May, 1991). Among studies dealing with children., this

variability is mostly observed for reflected appraisal measures. Most ofthe time, this appraisal

is assessed quite simply by using questions from the self-perception questionnaire reworded in

the third person, for example: "How smart do you think you are?" would be reworded as

"How smart does your mother/father think you are?" (e.g., Felson. 1989; Hergovich et al.,

2002). Using this rewording procedure enables to assess reflected appraisal at the same level

of specificity, that is, at the level ofthe studied self-perception domains.

In addition to this classic measure, reflected appraisal can also be assessed with Harter's

(1985b) social support scale. This scale measures a specific kind of social support: social

support in terms of appraisal. According to several authors, this kind of support is "what

symbolic interactionists refer to as reflected appraisal" (Heller, Swindle, & Dusenbury, 1986,

p. 467). Hence. Harter's seale ( 1985b) Is clearly announced as a mean to "directly examine the

link between the perceived regard from others and the perceived regard for the self" (Harter,

1999, p. 175). Consequently, when a relationship between this measure and global selfperception is observed, this is usually interpreted as supporting Cooley's hypothesis (e.g.,

Piek, Dworcan, Barrett. & Coleman, 2000; Robinson, 1995).

Yet, we argue that Harter's scale (1985b) may not be an appropriate measure to test

Cooley's hypothesis since several concerns can be raised about this measure. First, it assesses

the construct only at a general level: it does not differentiate between different domains.

Second, reading each item carefully reveals that items" content is quite general and affective.

Third, there is no strong construct validity evidence for this measure. More speciflcally. the

assumption that appraisal social support would measure something similar to reflected

appraisal never received empirical support. Moreover, to date, the relationship between actual

appraisal and appraisal social support is rarely considered. Consequently, the same is true for

the mediation hypothesis as a whole.

These criticisms leaded us lo hypothesize that the classic measure of reflected appraisal is

a better mediator than Harter's (1985b) social support scale. In order to test this hypothesis,

we took into account these two reflected appraisal measures.

In sum, the aim of this paper was to test Cooley's hypothesis about children's selfperceptions. We have pursued this general aim while testing two specific hypotheses; the first

one related to domains and significant others specificity and the second one related to

reflected appraisal measures.

Method

Participants

The study was conducted in an elementary school setting on 126 French children coming

from third grade (61 girls and 65 boys; aged 8 to 9) and their respective teachers (6). Children

took part on a voluntary basis and their parents had previously given explicit written consent.

One hundred and six parents also participated in the study.

Measures

Six scales were used. They were all translated (and reworded for questionnaire related to

parents and reflected appraisals) into French from the versions of Harter's questionnaires

(1985a,b). More precisely, three native French speakers did the translation. Afterward, a

OTHERS' APPRAISAL AND CHILDREN'S SELF-PERCEPTION

251

bilingual person living in the United-Stales for a long time performed a baek translation. In

addition, a bilingual person who was neither Freneh nor English native speaker evaluated the

resulting translation, It allowed controlling whether the meaning in Freneh and English

versions was identieal. When there were disagreements, the simplest sentenee was chosen in

order to be understood by ehildren.

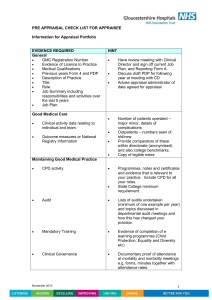

The question format was similar for the six scales (cf. Figure 1. Harter, 1999). In a first

time, for eaeh item, partieipants (i.e., children, parents and teachers) had to choose between

two opposite statements. For exatnple, in the self-perception profile, ehildren had to decide

whieh ehild was more like him/her (e.g., "Sotiie kids often forget what they leam but other

kids can retnember things easily"). In a seeond time, patiicipants had to assess whether the

statement was "Really true" for her/him or only "Sort of true" for her/him. Thus, for the six

scales, four answers were possible for all the items: a very positive one, a positive one, a

negative one, and a very negative one. Items were seorcd on a 4-point scale with higher seore

refleeting a better self-perception, social support, actual appraisal or reflected appraisal.

Really Sort of

true

ttiie

•

D

Son of Reallv

true

true

D

Some kids often forget

what they leam

D

This child is really good

al his/her school work

BUT

olher kids can remember

things easily

OR

tliis child can't do the

school work assigned

D

a

a

D

Figure I. Example ofthe question fomiat of H arter" s scales: one item from the SPPC (first)

and one from the TRS (second)

Self-perceptions. Children's self-perceptions were assessed with the .self-perception profUe

for chUdren (SPPC; Harter, 1985a). The SPPC is a 36-item self-report measure. It contains five

domain specific subscales {academic eompetenee, behavioral conduct, sociai competence,

physieal ability, and physical appearance) and a global self-worth subseale (not used in the

eurrent study). Eaeh speeific subseale consists of three positive items and three negative items,

for instanee "Some kids do very well at their classwork, but, other kids don't do veiy well at their

elasswork". An average score ofthe six items was computed with higher seores reflecting a more

positive children's self-perception. A Principal Component Analysis with oblique rotation

(PROMAX) was conducted on the 30 items. This analysis revealed a factorial structure

eonsistent with Harter's multidimensional approach, that is, the same five factors corresponding

to the flve domains we tnentioned earlier. Moreover, the ititemai consistency of eaeh subseale

was satisfaetory with Cronbach's alphas at .79 for physical appearance, .78 for behavioral

eonduct, .74 for seholastic competence, .67 for athletic eompetenee, and .63 for social acceptanee.

Note that two items were deleted for the social acceptance subseale. Correlations beiween

subscales ranged from .25 to .51 as is usually found in related literature.

Teacher's and parents' actua¡ appraisals. Teaeher's and parents' appraisals of children's

competences were assessed by the Teacher Rating Scale of children actual behavior (TSR;

Harter, 1985a). The TRS is a 15-item self-report measure. Form and eontent of this scale are

similar to the SPPC and taps the same domain speeifie subseales (scholastic eotnpetenee,

athletic eompetenee, peer likeability, physical appearance, and behavioral conduct). Eaeh

subseale eon,sists of three items, for instanee "This child is really good at his/her school work or

this child can't do the sehool work assigned". An average score ofthe three items was then

computed with higher scores refleeting a more positive actual appraisal. As reeommended by

Harter (1985a). the TSR was reworded in order to assess parents' appraisals about their own

ehild. An example of item is "My child is really good at his/her school work or my ehild can't do

252

C. NURRA & P. PANSU

the school work assigned". A Principal Component Analysis with oblique rotation (PROMAX)

was conducted on the 15 items for teacher and parents separately. These analyses revealed a

factorial structure eonsistent with Harter's supposition. Results of theses analyses also supported

Cole. Gondoli. and Pecke's (1998) findings about these scales, for teacher and parents. We

found the same five factors corresponding to the five domains. Furthennore. intemal consistency

was satisfactory for each subscale (respectively for teachers and parents, Cronbach's alphas were

.93 and .75 for physical appearance, .94 and .75 for scholastic competence, .93 and .65 for

behavioral conduct. .90 and .59 for social acceptance, and ,93 and .61 tor athletic competence).

Teacher '.v and parents ' reflected appraisals. Children's assessment of significant others'

beliefs about their competenee in five domains were measured with a scale adapted from the

TSR (Harter, 1985a). Here, children were asked to fill out a scale from another person's point

of view, one for his/her teacher and another for his/Tier parents. For example, "Your teacher

sees you like a child who does very well at his/her classwork or like a child who doesn't do

very well at his/her classwork". These two scales contain 15 items corresponding to the five

subscales tapping the same five domains of self-perception competence. Each subscale is

composed of three items. An average score of the three items was then computed with higher

score refiecting a more positive refiected appraisal. Two Principal Component Analyses with

oblique rotation (PROMAX) were conducted on the 15 items for teachers and parents

separately, 1 hese analyses revealed a five-faetor strueture for teachers but not for parents. For

the latter, the physical appearanee items did not load into a distinct factor. Consequently, we

did not take into account these items and the corresponding score. The intemal consistency for

each subscale was acceptable (Cronbach's alphas were, respectively for teachers and parents.

.68 for physical appearance. .68 and .59 for scholastic competence. .79 and ,71 for behavioral

conduct, -57 and .65 for social acceptance, and .76 and .60 for athletic competence).

Appraisal social support from teacher and parents. Children's perception of appraisal

social support from teacher and parents was assessed with the Social Support Scale for

Children (SSSC; Harter. 1985b), The SSSC is a 24-item self-report measure. It contains four

sources of support (teacher, parents, classmates and close friends). Each subscale consists of

three positive items and three negative items, for instance "Some kids have parents who like

them the way they are but other kids have parents who wish their children were different." An

average seore of the six items was then computed with higher scores refiecting a more positive

perception of appraisal social support. A Principal Component Analysis with oblique rotation

(PROMAX) was eonducted on the 24 items. It revealed a tactorial solution consistent wiih

what Harter found for this age. A three-factor structure emerged here: teacher, parents and

peers. Only teacher's and parents' appraisal social support were used in the eurrent study.

Their intemal consisteney were quite weak (Cronbach's alphas were .54 for teacher and .64

for parents). Note that one item was deleted for the parents subscale and three for the teacher

subscale. as they not only loaded on their factor but also on another factor. The correlation

between these two subscales is .26.

Procedure

Children's self-report scales were group administered in a classroom setting. Data were

collected at two time points in order not lo overload the children. The presentation order of the

scales was counterbalanced. The children were instructed on how to answer the ditferent

questions, and the experimenter told them that their results would remain confidential. The

items were read aloud and children filled out the questionnaire as the experimenter went

along. After they had eompleted all the scales, children were asked to give the scale

conceming the measure of parents" actual appraisal to their parents and to retum it when it

was filled out. Parents were requested to till out the scale together (when ihey both live in a

same place). Teachers were told to fill out the questionnaire when they wished to do so.

OTHERS' APPRAISAL AND CHILDREN'S SELF-PERCEPTION

253

Results

Correlations

In order to assess the relationships between teacher's and parents" aetual appraisal,

teacher's and parents' reflected appraisals, appraisal social support and reflected appraisals for

teachers and for parents, a correlation matrix was drawn up (Table 1 ).

Table 1

Correlations hetween teacher's and parents ' actual appraisal, teacher's and parents ' reflected

appraisals, appraisal social support and reflected appraisals for teacher and for parents

,^c^ua¡ appraisal

parents

with teacher

Reflected appraisals

parents

wilh teacher

Appraisal stK:ial

support wilh rellccied

appraisal for teacher

Appraisal social

suppi>rt wilh rcilecled

a^^raisal fur piircnLs

-.04

.31"

.34"

.45"

.17+

54«.

.63**

.67"

.76"

.19*

.19*

.13

.23*

,15

,52-'

,25"

,41"

Physical appeafBnce

Behavioral conduct

Swiai acceptance

Academic competence

Athletic compeicncc

„lO"

Note, *V^.UI; •ii<-,()5;twv. I».

These first results show that teacher's and parents' actual appraisals are eorrelated

although these correlations are sometime weak {rs from -.04 to .45). As far as refleeted

appraisals are concerned, children attribute in a large extent the same appraisal to their teacher

and parents (r.v from .54 to .76). Interestingly, a comparison of these last two sets of

correlation shows that children overestimate the similarity between teacher's and parents'

appraisals. The weakest presented correlations are between teacher's reflected appraisal and

appraisal social support (rs from .13 to .23). Finally, we ean observe that these correlations are

higher for parents {rs frotn .25 to .52). These last two sets of correlations are important as

reflected appraisals and appraisal social support are often supposed to assess the same

construct. Although they do appear correlated, these correlations seem a bit weak to support

the idea that they are assessing the same construct.

Test and comparison of the mediation of the actual appraisal effect on self-perception bv

appraisal .social support and reflected appraisals

We tested the following hypotheses. First, we expected that teacher's actual appraisal has

an effect on self-perception and this effect should be mediated by refleeted appraisal but only

for two specific domains: academic and behavioral eonduct. We also expected that parents'

actual appraisal has an effect on self-perception and this effeet should be mediated by reflected

appraisal for all the domains. Second, we expected that reflected appraisal should be a better

mediator than appraisal social support.

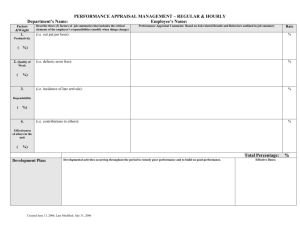

In order to test the mediation hypotheses, we conducted several mediation analyses' (for

teaeher and parents in the flve domains) following the steps suggested by Baron and Kenny

( 1986). In order to ilkistratc these analyses, the different steps of the analysis of the effect of

teaeher's actual appraisal on self-perception are represented in Figure 2. Hence, we first tested

c paths, that is. the predictor's (i.e., teacher's and parents' actual appraisals) global effect on

the outcome (i.e., self-perceptions). Seeondly. we tested a paths, that is. the predictor effect on

the potential mediators (i.e.. teacher's or parents' reflected appraisals or teacher's and parent's

appraisal social support). Thirdly, we tested h paths, that is, ihe mediators' effect on Ihe

C.NURRA&P. PANSU

254

outcome (controlling for the predictor). All these paths are tested controlling for the second

significant other- (cf. Figure 2, dotted line). For example, the effect of teacher's actual

appraisal on reflected appraisal (a¡) is assessed controlling for the effect of parents' actual

appraisal on this mediator. In order to argue for mediation, c, a, and b must be found

significant at the same time (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

Teacher's actual

appraisals

c

Self-perception

_ . . - • ' ' '

Parents'

Self-perceplicin

Parents' appraisal

social support

|

Figure 2. Example of the tested model for the multiple mediation of teacher's actual appraisal

on self-perception by teacher's reflected appraisal and teacher's appraisal social

support controlling by parents' relative measures in doted lines

In addition, we tested the signifieanee of the indirect effects {a*b, a test that is equivalent

with testing the decrease in the effect of actual appraisal on self-perception once the mediator

is controlled, in other words testing the difference between c and c'). This test allows

assessing whether reflected appraisal or appraisal social support mediates the effeet of aetual

appraisal on self-perception. In order to test this indirect effect, we relied on the macro

proposed by Preacher and Hayes (2008) instead of the commonly used Sobel test. We did so

because this enables to test indirect effects relying on bootstrapping and the mediation

literature tells us that bootstrapping is more statistically powerful (e.g., Fritz & MacKinnon,

2007; Shrout & Bolger. 2002).

Finally, this macro allows us to test our hypothesis relating to the comparison of

mediators. Indeed, it gives the opportunity to consider several mediators at the same time and

to test whether a specific mediator is better than another is (i.e., a¡*b,>a2*b2)., again by

relying on the bootstrap methods. Therefore, with this macro we will be able to test whether

reflected appraisal is a better mediator than appraisal social support.

Test of c paths. This analysis tested whether actual appraisal has an effect on selfperception. As can be seen in Table 2. results show that it was the case only for some

domains: Teacher's actual appraisal effect on self-perception was significant only for social

OTHERS' APPRAISAL AND CHILDREN'S SELF-PERCEPTION

255

acceptance, b=0.244. H95)=2.30. p<.03. Parents' actual appraisal efTect on self-perception

was significant only for academic competence. /i=C.288. i(94)=2.57, /;<.O2. and social

acceptance, ¿^0.407./(95)^3.25,/j<.01. Hence, in these domains, the higher the teacher's and

parents" actual appraisals, the higher were the self-perceptions.

Test of a paths. This analysis tested whether children perceive significant others' actual

appraisal. In other words, it tested how actual appraisal is linked to reflected appraisal. These

results revealed that teacher's actual appraisal effect on teacher's reflected appraisal was

significant for academic competence, ^=O.I84, /(94)=2.21,/)<.O3, and behavioral conduet,

/)=O.23O, /(92)=2.49./;<.O2. Parents' actual appraisal effect on parents' reflected appraisal

was significant for social acceptance, /)=0.421, /(95)=3.55, p<.Q\) and was marginally

significant for academic competence. A^0.20I, i(94)=1.82. /)<.O8, and behavioral conduct,

¿=0.261, /(92)=1.72,/j<.09. Therefore, for these different combinations, the higher the

significant others' actual appraisal, the higher was the reflected appraisal. Note that for

teacher, actual appraisal effect on appraisal social support was not reliable for all the domains.

For parents, it was marginally significant only for physical ability. A=-O,2O2, r(93)=l.73,

/?<.O9, This effect, however, was in the opposite direction of what could be expected. Indeed,

in this case, a higher value of actual appraisal was associated with a lower value of appraisal

social support.

Table 2

Summarization ofthe different steps ofthe mediation analysis for the five domains and the two

significant others

c

Teacher's AA Academic competence

Behavioral conduct

S11 ¡ipt cesión

0.072

-0,007

0,069

-0,042

Social accqilance

0,244*

0,172'*'

Physical abiJiry

0,123

0,067

Physical appearance

Parctits'AA

c'

Academic competence

0,173

0,288*

0.158

0.13Rt

Behavioral conduct

0,170

0,031

Social acceptance

0,407**

0,267t

Physical ability

0 125

0.046

Teacher/academic eompeience 0,111

Parents.'physical ability

0.220''"

-0.007

(MM6

a

b

il-1-1

RA

ASS

RA

ASS

RA

ASS

RA

ASS

RA

ASS

0,184»

-0,122

0,2.10*

0,041

0,070

-0,061

0,129

0.078

-0.096

0.086

0.348**

0,160*

0,29.S-*

-0,005

0,105

0,0i>5

0.312**

0,010

0.424**

0,144

0,{)65*

-0,020''"

0,067*

RA

ASS

RA

ASS

RA

ASS

RA

ASS

0.20 i t

0,066

0,261 +

0,073

0.421**

-0.1(7

0.20]

-0,202"''

0.272**

0,221**

0,310*0,174

0,311*

0.182

0,285**

0.301**

0.054t

0,014

0,080'''

0.009

0,127*

-0,020

0,059'''

RA

RA

0,206*

0.254''"

0,348-*

O,2H5**

0,072*

0,076*

O,(X)1

0,00«

-0,006

0.03 H

0.005

-0,041

>!'¡!b,)

0,084*

0,066*

0,014

0.0.18

-0.054

0,013

0,041

0,071

0,147*

0,122*

-0.063*

_

Note. AA=actual appraisal, RA=reflected appraisal, ASS=iippraisal sociai support; Indirect ctTect=(a*b). Mediators

comrast=(a|b| vs. a2b2); Coefficient in the tableare unstandardized one (b); **/i<,01; *p<.05; \p<,\Q.

Test of h paths. This analysis tested whether the mediator had an effect on self-perception

controlling for actual appraisal. Teacher's reflected appraisal effect on self-perception was

significant for four domains: academic competence, /)^0.348. i(90)=4.31,/3<.O1, behavioral

conduct, /)-0.295, i(88)=3.30, /X.Ol. physical ability, /)=0.312, /(89), p<.OI, and physical

appearance, A=0.424, i(89)-4.09, p<.Ö\. Parents' reflected appraisal effect on self-perceptions

256

C. NURRA & P. PANSU

was signifieant for four domains: academic eompetence, />=0.272, r(90)=2.75, p<.Ol,

behavioral eonduct, /i=0.310, /(S8)-3.41./J<.01, social acceptance, /f=0,31l, /(91)=2.57,

p<.02. and physical ability, h^0.2H5. t{^9)=2.W, p<.0]. Therefore, for these different

eombinations. the higher the significant others" reflected appraisal, the higher was selfperception. The same analysis concerning appraisal social support revealed several significant

effects. Teacher's appraisal soeial support effeet on self-perception was significant for

academic competence, b=0.\60. ^(90)^2.43, / J < . 0 5 . Parents' appraisal social support effect on

self-perception was signifieant for aeademie competence, /)=0.22l, í(9Ü)=2.65, /K.Ol, and

physical ability, A=(1.2H5, /{89)=3.36. p<.0\. Therefore, for these different combinations, the

higher the signifieant others" appraisal soeial support, the higher was self-perception.

Test of indirect effect and tnediators contrast. With the following analyses, we tested two

things. On the one hand, we tested whether aetual appraisal has an indirect effect (a*b) on

self-perception through the mediators. On the other hand, we tested if reflected appraisal was a

better mediator as compared with appraisal social suppotn (ajbj vs. ajb^).

As far as teacher is concemed, the first analysis revealed that teaeher's actual appraisal

indirect effect on self-perception through refleeted appraisal was significant for academic

eompetenee. PE=0.065. Cl^,{0.Í)(i9. 0.142)'. and behavioral conduct, PE=0.i)66. a„,-(0.012,

0.166). We also found that teacher's indireet effeet through appraisal soeial support was

marginally signifieant only for aeademie eompetenee, PE--0.Q20, C/9,,(-0.057,-0.001). The

second analysis revealed that reflected appraisal was a better mediator than appraisal .soeial

support for aeademie competence, /'£=0.084, C/y,(0.024, 0.174) and behavioral conduct,

PE=0.066. r/y,(0.012, 0.173). Thus, for teacher, indirect effeets through refleeted appraisal

were larger than indirect effeets through appraisal social support for these two domains.

As far as parents are concemed, the first analysis revealed that parents' aetual appraisal

indireet effeet on self-perception through reflected appraisal was signifieant for social

acceptance, P£^I27, C/ÇÎ(0.027, 0.317). It was only marginally significant for academic

eompetenee. ^£=0.054, C/,;„(0.013, 0.137), behavioral conduct. /'£=0.080, C/y,,(0.004,

0.249), and physical ability, PE=().(i59, 0^,(0.007, 0.165). The second analysis revealed that

reflected appraisal was a better tnediator than appraisal social support for social acceptance.

P£=0.147. C/55(0.053, 0.365). and physical ability, PE=0.\22, C/y,(0.032, 0.260). Thus,

parents' indirect effects through reflected appraisal were larger than the indirect effects

through appraisal social support for these last two domains.

Additional analyses. We obser\'ed thai the effect of teaeher's aetual appraisal on selfperception was positive while the indireet effect of teacher's actual appraisal on selfperceplion through appraisal social support was significant and negative. Thus, we can

eonelude that appraisal social support is not a mediator bul a suppressor - once the appraisal

social support is controlled, the effect of actual appraisal is larger and not smaller. The satiie

conclusion can be drawn for parents' actual appraisal in the physical abiliiy domain. Since a

suppressor variable reduces the magnitude of a global effect when it is not controlled, we

tested again these global effeets but eontrolling tor appraisal social support, Results showed

that the aetual appraisal global effect for teacher is still non significant, b^Q.\ 11, /(93)=1.52,

p<.\4. Yet. it appeared marginally reliable for parents in physical ability domain, /Ï=0.220.

Conclusion on the hypotheses

Concerning the first hypothesis (i.e., domains speeificity), we ean conclude in favor of a

mediation effect when we observe a signifieant effeet of the paths c, a, b and a*b. As for

teaeher, results in aeademie eotnpetenee and behavioral conduct domains partially support the

mediation hypothesis. We found a signifieant teaeher's aetual appraisal effect on refleeted

appraisal (i/ path), a signifieant refieeted appraisal effect on self-perception (b paths) and a

OTHERS' APPRAISAL AND CHILDREN'S SELF-PERCEPTION

257

significant indireet effeet (a*b). Yet. we did not found a significant c path (i.e.. the global

effect of actual appraisal on self-perception was not significant) tor these two domains. As for

parents, results lead us to conclude, with some reserve, that the effect of actual appraisal on

self-perception is mediated by rctlected appraisal for the four domains: academic competence,

behavioral conduct, social acceptance, and physical ability. Note, however, that some effects

were only marginally significant: the a path and the indirect effect for academic competence

and behavioral conduct, and. the c path and the a path for physical ability. Furthermore, we

did not observe a significant effect for c path on behavioral conduct. Finally, none of the

indirect effect was significant by appraisal social support.

Conceming the second hypothesis (i.e,, comparison of mediators), we can conclude that

reflected appraisal is a better mediaior than appraisal social support when we observe a

significant contrast between the two potential mediators or when appraisal social support is a

suppressor. Our results support this hypothesis for teacher. Indeed, teacher's retiected

appraisal was a better mediator than appraisal social support for academic competence and

behavioral conduct domains, Bui. for parents, the results only partially supported our

hypothesis. We observed that retlected appraisal is a better mediator for social acceptance and

physical ability domain, but not for academic competence and behavioral conduct.

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to test Cooley's (1902) hypothesis eoneeming the constmction

of self-perceplion. that is. the mediation of the actual appraisal effect on self-perception by

refiected appraisal. According to Cooley ( 1902). the self is shaped by social interactions. From

this standpoint, significant others represent a social mirror: our self-perception is what we

imagine others think about us. In today's temi, the effect of actual appraisal on self-perception

would be mediated by refiected appraisal, Firsi. we predicted that this mediation should occur

only when children receive repeated feedback from significant others. Therefore, we

hypothesized that this mediation would occur in academic and behavioral conduct domains for

teaeher and in all the domains for parents. Second, we hypothesized that reflected appraisal

assessed in a classical way would be a better mediator than appraisal social support (with

Harter's scale. 1985b).

As a whole, despite some marginally significan! results, our data provide some support lo

our first hypothesis by suggesting that the mediation through retlected appraisal can be tbund

within specific combinations of domain and significant others. The clearest exceptions to this

general pattern have to do with the effect of actual appraisal effect on self-perceplion. We

found thai this etïeet is not reliable in the two domains where it was expected for teacher's

actual appraisals (i.e.. academic competence and behavioral conduct). This effect was also not

significant for parents in the behavioral conduct domain. Although we expected these

relationships to be significant, they were the most likely not to be significant. Indeed,

according to Shrout and Bolger (2002). this type of effect (i.e.. the c path in the mediation

analysis) being more distal ihan the other meditational paths, a larger statistical power is often

required. They further argue that this is even more so with correlational designs like ours.

They conclude that in such a case these c paths do not appear necessary to demonstrate the

existence of a mediation. Therefore, with these restrictions in mind, we could consider that our

results support the first hypothesis. As expected, there are specific others who have an impact

on specific domains depending on how much feedback these others provide to the children. In

this study it was the case for teacher in two domains (i.e., academic eompetence and

behavioral conduet). as well as for parents in the four domains under scrutiny (i.e., academic

cotnpetence, behavioral conduct, social acceptance, and physical ability).

The results obtained in this study are useful for two reasons. First, it seems possible to

predict when retlected appraisal mediates the relationship between actual appraisal and selfperception: significant others infiuence children's self-perception through refiected appraisals

258

C. NURRA & P. PANSU

only when we can suppose that they provide enough feedbaek. Second, our results extend

previous work, wliicii demonstrated that self-perception is more or less influenced by others'

perception as a ftinction of trait characteristics (e.g., trait stability, Cole, 1991) or population

characteristics (Cole, Jacqucz. & Maschman, 2001). Indeed, in addition to these

characteristics, our results reveal that it is also important to study the proper combinations of

domains and signiflcant others.

As far as the second hypothesis is concerned, our results confirm that reflected appraisal

(as it is classically measured) is often a better mediator than appraisal social support. Hence,

with only two exceptions (i.e.. parents in acadetnic competence and behavioral eonduct

domains) we found that indirect effects through reflected appraisal were larger than indirect

effects through appraisal social support. Moreover, we observed no signifieant mediation

through appraisal social support. In fact, we even found evidence that not only appraisal social

suppon was not a mediator, it happened to play the role of a suppressor twice in our data.

Taken as a whole, these results are critical because in the literature reflected appraisal and

appraisal social support are often presented as two measures of how children think others

think about them. Our results suggest, however, that these measures are not equally

appropriate to test Cooley's hypothesis. This conclusion only stands for Harter's measure of

appraisal social support, and it cannot be generalized to all appraisal social support measures.

Yet. these results are important because Harter's measure is often used to assess Cooley's

hypothesis (e.g.. Harter. 1999; Piek, Dworcan, Barret. & Colcman. 2000; Robinson. 1995).

Our study has at least two main limitations. The first issue that could be raised eoncerns

the causal relationships implied in our hypotheses. The fael that variables have not been

induced does not allow us to draw strong conclusions on this ground. We can only argue that

our results are in line with our theoretical reasoning. Still, the direction of some of these

relationships could be debatable. For instance, it can be possible that the relationship between

refleeted appraisal and self-perception is opposite to what we suggested earlier, that is. what

Felson (1989) refers to as a projection effect. We see two reasons, however, to doubt that the

projection effect would explain in and on itself the effect we observed. On the one hand,

research has shown that the same mediation we studied has already been observed in a

longitudinal design with parents in the physical ability domains (Bois et al., 2005). Although

longitudinal designs have their own issues as far as causality is concerned (e.g., a third

variable could still explain the observed relationship), it is still an argument in favor of a

eausal relationship. On the other hand, we believe that the whole mediation pattern we

observed would be less likely if a projection effect was at stake. If it was. there would be no

reason for the actual appraisal effeet on self-perception to be significantly reduced after

controlling for reflected appraisal. Therefore, although we have to be careful with our results,

they still bring important insights on how to study the mechanisms that account for the impact

of significant others' appraisal on self-perception. This comment leads us to the second

limitation.

Our first hypothesis relied on the idea that it is only when children get feedbaek from a

signifieant other that his/her judgment has an effeet on self-pereeption through refleeted

appraisal (Funder & Colvin, 1997; Jussim et al., 1992). In our study, we assumed that feedback

is actually more frequent for teacher on academic competence and behavior and on all the

domains for parents. Although this assumption seems rea.sonable, we have no data to strengthen

this argument. In addition, we know thai feedback can vary in its content (e.g.. valence) and

nature {e.g.. these feedback can suggest ways for improvement) (Nareiss, 2004). Therefore,

one might suppose that the mediation we studied may not only depend on feedbaek frequeney,

but also on other feedback attributes (as content or nature). We should also mention that

maybe feedback could influence self-perception without being perceived consciously. For

example, we have seen that for teacher in the social acceptance domain, actual appraisal had a

signiflcant effect on se If-percept ion, but we did not found an effeet of actual appraisal on

reflected appraisal, nor an effect of reflected appraisal on self-perception. This suggests that

others' aetual appraisal can sometimes aftect self-pereeption without the children being able to

perceive how others see them. Therefore, it seems that in order to go further into our

OTHERS' APPRAISAL AND CHILDREN'S SELF-PERCEPTION

259

hypothesis, it will be necessary to control the fact that feedback is more frequent when the

mediation occurs and to take into account feedback attributes. Doing so should be helpful to

understand the process by which significant others' appraisal influences self-perception.

Despite these limitations, this study shows how important it is to rely on the appropriate

signifieant others and domains combinations in order to understand the construction of

children self-perception. Furthermore, although peers do not seem to play a role as important

as teacher and parents with children of the age we studied here (Sarason. Pierce, Banneniian,

& Sarason, 1993). we can question iheir impact in this process. Following the same reasoning,

we can expect that their actual appraisal will also have an effect on specific domains. Future

studies should be devoted to analyzing this question.

Notes

'

Two ihings have to be noticed about ihc analyses we eonducted, Fir.sl, for each analysis, we eliminaied participants who

presenied aberrani data (outliers). To ihal end. we used studcmizod deleted residuals. Cook's dislances itnd leverage

value as indicaiors (Judd & McClelland. I^SQ). Tins melhod involves thai ihe outliers are specific tn a model (beeau.se

with these Ihree indicators, we evaluate the ouilier on X, Y. and the link between X and Y). Consequently, the iuitlicrs

detected are not the sattie in all the analyses. However, we deleted ihe sattie participants fbr the analyses of one domain

in order to tesi Ihe mediation always with the same panieipanis. Second, we lested gender a.s a moderator of ihe elTeeis.

It is not a moderator so we did noi eonsider it in our analyses.

-

Here the daia are noi independent. IndL-i?d, they can be regarded as more similar wilhin classrooms thnn between

elassrooin.s. This should be parlieiilarly true with teaeher's acUial appraisal as only one teacher jiidgcii all the

children ofone classrootn. In order to lake into aeeourtt this rton independence, we enicred the class as a eovariaie in

all otir slalistical tnodols.

Note thai bootstrapping provides poinl estimates (PC) ihat are a mean estimation of se\eral iterations of whai is

calculated (here indirect elTect and contrast comparing mediators). Their signilleanee is deieniiincd with confidence

intervals (Cl). If ihe zero is not contained in the confidence inler\al. ii means that the ptiini esiimate is signiflcanlly

(Jiiïcrenl from zero. We calculated confidence intervals for/)<.05 (a 95% confidence interval. Clijsi. WHien i( is not

significant at this point, we calculated confidence interval for/K.lO (a 90V'o confidence interval, Clqo). Menee, in ihis

first example, PE-0,Ü65. Clqj (l),0Ü9. 0,142). this, means thai on average a*b=0.065. Moreover, ihe confidence interval

al 95% docs noi includeO which tneans Ihal this PE (i.e., the indirect cftceI) is significantly different fromOat/K.O.'i,

References

Baron. R.M.. & Kenny, D.A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable disiinelion in .social psychological researeh:

Coneeptual, strategic, and staiistical con.siilerations. Journal of Personality andSixiiil Psychohg\\ 51. 1173-1182,

Bois. J.E,. Sarrazin. P,G,, Brustad, R,J., Chanal. J,P., & Trouilloud, D.O, (2005), Parents" appraisals, reflected

appraisals, and children's self-appraisals of sport competence: .A yearlong study. Journal of Applied Sport

P.'.ychology. / 7. 273-289.

Boivin, M,. Vitaro, F,. & Gagnon, C, (1992), A reassessment of the SelT-Perceplion Profile lor Children: Factor siructure.

reliability, and convergent validity of a Freneh version among second through sixth grade children. International

Journal of Behavioral Development. 15. 275-290.

Bressoux. P., & Pansu, P, (2003). Quand les en.teignants Jugent leurs élèves. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Chambers, J,R., Epley, N., Savilsky, K,, & WindschitI, P,D, (20()S), Knowing loo much: Using privaie knoviledge Io

predict how one is viewed by oiher.s. Psychological Science. 19. 542-548,

Cole. DA, (1991), Change in sell-perceived competence as a liinction of peer and teacher evaluation. Dcvehpmerital

P.sychohgy. 27. 682-688.

Cole, D,A,, Ootidoli, D,, & Peeke. L. (1998). Structure and validiiy of pareni and leaeher pereepiions of children's

eompetence: A multitrait-multimethod-miilli group investigaiion. Psychological Assessment. 10. 241-249,

Cole, D.A., Jacquez, F.M., & Ma.schman, T.L. (2ü[)l), Social origins of depressive cognitions; A longitudinal siiidv ai

self-perceived competence in ehildren. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 25, 377-395,

260

C. NURRA & P. PANSU

Cole. D.A., Maxwell, S.E., & Marlin. J.M. (1997), Reflected sclf-appraisals: Strength ynd siructure of the relation of

teacher, peer, and parent ratings to children's sell-perce i ved competencies. Journal vj Educatiimat Psychology, ÄV,

55-70,

Cole, D.A., Maxwell, S.E., Martin, J,M.. Peeke. L.G,, Seroc/ynski. A.D., Tram. J.M,. Hoffman. K,B., Ruiz. M,D.,

Jacqutv, F., & Ma.schman, T, (2001), The dcvelopmeni of multiple domains of child and adolesceni self-concept:

A cohort sequcniial longiludinal design. Child Development. 12, 1723-1746,

Cook, W.L., & Douglas, E. M. ( IWH). The looking-glass self in family context: A social relafiotis analysis, .iournut t>f

Family Psycholoff.\ 12. 299-309,

Cooley, C.H, (1902), Human nature and the .social order {]')M ed,}. New York: Scocken Books,

Felson. R,B, ( 19H^). Retlccicd appraisal and the developmcnl of self. Social P.-iVchohg}' Quarterly. XV, 71-78,

Felsoti, R.B. (IV89). Parents and the reflected appraisal process: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and

Social P.Kvehohgy, .^6, 965-971,

Friiz, M.S,, & MacKintion. D.P, (2007), Required sample si/e to delect the mediated elïeei. Pwchohgical

233-239.

Science. IH.

Funder, D.C. & Colvitt, C,R, (1997), Congruence of others' and self-judgmenis of personality. In R. Mogan. J. Johnson,

& S, Briggs (Ed^.). Handhíwk ofper.wnaliiy psychology {pp. 617-647): Academic press,

Gest, S.D., Domitrovich, CE., & Welsh. J.A. (2005), Peer academic repulation in elementary school: Ahsocialiori with

changes in self-ctincepl and academic siiiWa. Journal of Educational P.-iyehology, 97. 337-346,

Han. D,, Aikins, R,, & Tursi, N. (2006). Origins and Dcvelopmenlal Influences on Self-E.stcem, In M,H, Kemis (Ed.),

Self-esteem issues andan.swers: A sourcehook of cttrrent perspectives i,-^-[>- 157-162), New York: Psychology Press.

Harter, S. (1985a). Manual for the .telf-perception profile for children. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Harter, S, ( 1985b). Manual for the social support scale for children. Denver. C"O: University of Denver.

Harter, S, (1999), The constniction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford,

Heller, K,, Swindle, R.W., & Dusenbury. L, (1986). Component social suppon processes: Comitients and integration.

Journal tif Consulting and Clinical Psvcholog}-. 54. 466-470.

Herbert, J,. & Stipck, D, (2005). The emergence of gender differences in children's perceptions of their academic

competence. Applied Developmental P.sychology, 26, 276-295.

Hergovich, A.. Sirsch. U., & Felinger, M, (2002), Sell-appraisals, actual appraisals and reflecled appraisals of

préadolescent children. Social Behaviour and Persotialit}\ 3U. 603-612.

Judd, C M , , & McCleiland, G.H. (1989). Data analysis: A model comparison approach. New York: Harcoun Brace

Jovanovich,

Jussim, L, {1986), Self-fulfilling prophecies: A theoretieal and integraiive review, Psychologictil Review. V.i, 429-445,

Jussim. L., Sotiln, S,, Brown. R,, &. Kohlhepp. K, (¡992). Untiers Land ing reactions to feedback by integrating ideas from

symbolic interaction ism and cognitive evaluation theory. Journal tjf Personality and Social P.sycholog\\ (>2, 402-421.

Leary. M,R, (2006), To what extent is self-esteetn influenced by interpersonal as eompared with intrapersonal

processes? Whal are these processe.»;.' In M.H. Kcmis (Ed,), Selfesteetn I.V.VMC.V atid atiswer.^: A .wuriehook of

current perspectives (pp. 195-200), New York: Psycholog)' Press.

Malloy, T.E., Albright, L., Kenny. D.A,, Agatstein. F,. & Winquist. L. (1997), Interpersonal perception and

tnetaperception in non overlapping social groups, .hiinutl of Personality und Social Psycholog); 72. 390-398.

Markus. H„ & Cross, S. (1990). The interpersonal self. In L,A. Pcrvin (V.o.). llundhook ofpcrsonnality.

research (pp, 576-608). New York. London: The Guilford Press,

Theoiy and

Markus, H., & Wurf. E, (1987). The dynamic self-concept: A social cognitive perspective. Annual Review of

Psychology, }H, 299-337.

Narciss, S, (2004). The impact of informative tutoring feedback and seif-efllcacy on moiivaiion and achievement in

eoncepl leaming, E.\perimental Psychology. .'>/. 214-228,

Piek, J,P,. Dworcan. M.. Barreti, N.C, & Coleman. R. (2000), Determinants of self-wonh in children with and without

developmental coordination disorder. International Jmtmal of Disability, Development and Education, 47. 259-272,

OTHERS' APPRAISAL AND CHILDREN'S SELF-PERCEPTION

261

Preacher. K..I., & Hayes. A.F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for a.ssessing and comparing indirect effects

in simple and multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 40, K79-89I.

Robinson. N.S. ( 1995). Evaluating the nature of perceived support and its relation to perceived self-worth in adolescents.

Journal ofResea)Th on Adolescence, 5. 253-280.

Sarason. B.R., Pierce, G.R., Banncmian. A.. & Sarason. I.G. (1993). investigating the antecedents of perceived social

support: Parents' views of and behavior toward tlieir children. Journal of Per.wnality and Social P.sychology, 65,

1071-1085.

Shrauger, J.S., & Schoeneman. T.J. (1979). Symbolic interdctionis! view of self-concept; Trough Ihc Itwking glass darkly.

Psychological Bulletin. 86. 549-573.

Shrout, P.E., & Böiger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental sludies: New procedures und

recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7.422-445.

Wood, J.V., & Wilson, A.E. (2003). How important is social comparison, hi M.R. Leary & J.P. Tangney (Eds.).

Handbook of .iielf and identity (pp. 344-3fi6). New York, London: The Guilford Press.

Le but de eel article est d'étudier la construction des perceptions

de soi des enfants ¿i partir de l'hypothèse de Cootey (1902). Plus précisément, nous nous intéressons à ¡a médiation de l'effet du Jugement

des personnes signifiantes sur ¡es perceptions de soi par ¡a perception

de ce Jugement (i.e., perception prêtée)- Premièrement, nous faisons

/ 'hypothèse que cette médiation sera observée uniquement dans ¡es

domaines oii ¡'enfant reçoit des feedback d'une personne signifiante

(ici l'enseignant ou ¡es parents). Deuxièmement, nous avons pris en

compte deux mesures de perceptions prêtées pouvant être considérées

comme éi/uivaientes: une mesure dassique ct une mesure de soutien

social d'approbation (Marier, 19H5b¡. Nous faisons ¡'¡lypothése qtie les

perceptions prêtées mesurées de manière dassique seraient un tneiHettr

médiateur de l'effet du Jugetnent des personnes signifiantes sur ¡es

perceptions de ."ioi que ¡a mesure de soutien .socia¡ d'approbation. Afin

de tester ces ¡lypothèses, nous avons conduit une étude auprès de ¡26

enfants ¿îgês de 8-9 ans, de 106 parents et de sLx enseignants. Pris dans

¡eur ensemb¡e. ¡es résu¡tats voni dans ¡e .sens dc nos hypothèses.

Key words: Actual appraisal. Appraisal soeial sitppoti. Children's self-perception. Reflected

appraisal.

Received: March 2úm

Revision received December 2008

Cécile Nurra. Laboratoire In ter-Un i vers i ta i re dc Psychologic, Uiiivcrsitc de Oreiioble, France. E-mail:

cecile.nurra@univ-savoie.fr; Web site: www.lip.iiniv-siivoie.rr

Current theme of research:

Her main interest of research is about ibe constmction of self-evaliialions. She is interested in the way signiflcant others'

(namely parents, peers and teacher) actual appraisal inlluences self-evaluations. She is particularly interested in the

impact of aciual self and ideal self, and more specifically on the impact of Ihe perceplion of temporal distance between

ideal self as a goal and the present.

262

C. NURRA & P. PANSU

Most relevant publications in the field of P.\vcholog}- of Educalion:

Joet. G,. NiirTa. C . Bressoux, P,. & Pansu, P, (2007), Le jugement scolaire: Un dctemiitiatit des croyances sur soi des

élèves, Psycholngie ei Education. 3. 23-40,

Nurra, C. (2008), L'estime de soi. In M. Bouvard (Ed,). Echelles et questionnaires d'évaluation de l'enfant et de

l'adolescent (pp, 47-64). Paris; Masson,

Pascal Pansu. Laboratoire des Sciences de l'Education, Equipe Perspectives Sociocognitives,

Apprentissages et Conduites Sociales. Université Pierre Mendcs France. 1251 Avenue Centrale, BP

47, 3íí040-Grenoble, France, E-mai!: pascal,pansu@upmf-grenoble.fr

Current iheme ol research:

His main research Tocuses un social judgment norms, the evaluative knowledge and on the two fundaînental dimensions

of social judgment: swial desirability and social utiliiy. His highesl research interesis also concem teachers' judgments

and iheir effects on pupils' self-concept. They also include the impact of the siigmati/alion on cognitive perfonnances

(e.g.. school periontiances).

Most relevant publications in the field of Pxycholog\'of Education:

Bressou.\. P.. & Pansu. P, (2007), A methodological shortnole on measuring and assessing the effects of normative

clearsightedness about intcmahty. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2. 169-17B,

Dompnicr, B,. Pansu, P,. & Bressoux. P, (2007), Social utility, social desirability and scholastic judgments: Toward a

personological model of acadetnic evaluation, European Journal of Psyehology of Education. 3. 333-.T50.

Pansu. P, (2006) The intcmalit)' bia.s in social Judgments: A sociocognitive approach. In A, Columbus (Ed,). Aihances

in psychology research (vol, 40. pp. 75-110). New York: Nova Science Publishers,

Piinsu. P,. ÍSL Gilibori. D. (2002). Effect of causal explanations on work-related judgment. .-Applied Psycholog)^: An

Intertiational Review. .5/(4). 505-526.

Pansu. P.. Dubois. N.. & Dompnier. B. (2008). Intemalily-nomi theory in educational contexts, European Journal of

Psychologv of Education, 4. 3S5-397.

Pansu. P.. Bressoux. P.. & Louche. C. (2003), Theory of the social norm of intemality applied to education and

organ i/ill ions. In N, Dubois (Ed,), ,4 sociocognitive approach to social norm.': ('Çi'p. 196-230). London: Routledge.