CAUSES of the American Revolution ACTS SEDITION ACT is a

advertisement

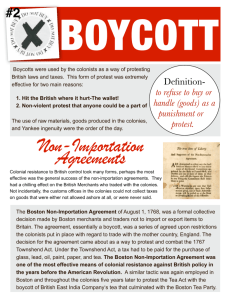

CAUSES of the American Revolution ACTS SEDITION ACT is a common law offense that is less than treason but that may be preliminary to it. The new law said that citizens could be fined or jailed if they criticized elected officials. ALIEN ACT allowed the President to expel any alien or foreigner who he thought was dangerous to the country. Four international security laws passed by the U.S. Congress restricting aliens and curtailing the excesses of an unrestrained press, in anticipation of an expected war with France. After the XYZ Affair (1797), war appeared inevitable. Federalist, aware that French military successes in Europe had been greatly facilitated by political dissidents invaded countries, sought to prevent such subversion in the United States and adopted the alien and Sedition acts as part of a series of military preparedness measures. The Three alien laws, passed in June and July, were aimed at French and Irish immigrants, who were mostly pro-French. These laws raised the waiting period for naturalization form 5 to 14 years permitted the detention of subjects of an enemy nation, and authorized the chief executive to expel any alien he considered dangerous. The Sedition Act (July 14) banned the publishing of false ore malicious writing against the government and the inciting of opposition to any act of Congress or the president particles already forbidden by state statutes and the common law but now by federal law. The federal act reduced the oppressiveness of procedures in prosecuting such offenses but provided for federal enforcement. The acts were the mildest wartime security measures ever taken in the United States, and they were widely popular. Jeffersonian Republicans vigorously opposed them, however, in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, which the other state legislatures either ignored or denounced as subversive. Only one alien was deported, and only 25 prosecutions, resulting in 10 convictions, were brought under the Sedition Act. With the war threat passing and the Republicans winning control under the federal government in 1800, all the Alien and Sedition Acts were repealed during the next two years. QUEBEC ACT set up a government for Canada and protected the rights of French Catholics. Act of the British Parliament that vested the government of Quebec in a governor and council and preserved the French Civil Code and the Roman Catholic Church. The act was an attempt to deal with major questions that had arisen during the attempt to make the French colony of Canada a province of the British Empire in North America. Among these were whether an assembly should be summoned, when nearly all the inhabitants of the province of Quebec, being Roman Catholics, would, because of the Test Acts, be ineligible to be representatives; whether the practice of the Roman Catholic religion should be allowed to continue, and on what conditions; and whether French or English law was to be used in the courts of justice. The act, declaring it inexpedient to call an assembly, put the power to legislate in the hands of the governor and his council. The practice of the Roman Catholic religion was allowed, and the church was authorized to continue to and oath of allegiance substituted so as to allow Roman Catholics to hold office. French civil law continued, but the criminal law was to be English. Because of these provisions the act has been called a generous and statesmanlike attempt to deal with the peculiar conditions of the province. At the last moment additions were made to the bill by which the boundaries given the province by the Proclamation of 1763 were extended. This was done because no satisfactory means had been found to regulate Indian affairs and to govern the French settlers on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. It was decided, therefore, put the territory between the Ohio and the Mississippi under the governor of Quebec, and the boundaries of Quebec were extended southward to the junction of the Ohio and the Mississippi and northward to the height of land between the Great Lakes and the Hudson Bay. This provision of the act, together with the recognition of the Roman Catholic religion, was seen to threaten the unity and security of British America by, in effect, reviving the old French Empire destroyed in 1763. The American colonists viewed the act as a measure of coercion. The act was thus a major cause of the American Revolution and provoked an invasion of Quebec by the armies of the revolting colonies in the winter of 1775-76. Its provisions., on the other hand, did little at the time to win French support of British rule in Quebec; and, expected for the clergy and seigneurs, most of the French remained neutral. The act eventually became important to French Canadians as the basis of their religious and legal rights. TEA ACT the act did away with some taxes paid by the company. In British colonial history, legislative maneuver by the British ministry of Lord to make English tea marketable in America. A previous crisis had been averted in 1770 when all the Townshend Acts duties had been lifted except that on tea, which had been mainly supplied to the Colonies since then by Dutch smugglers. In an effort to help the financially troubled British East India Company sell 17,000,000 pounds of tea stored in England, the Tea Act rearranged excise regulations so that the company could pay the Townshend duty and still undersell its competitors. At the same time, the North administration hoped to reassert Parliament's right to levy direct revenue taxes on the Colonies. The shipments became a symbol of taxation tyranny to the colonists, reopening the door to unknown future tax abuses. Colonial resistance culminated in Boston Tea Party (December 1773), in which was dumped into the ocean, and in a similar action in New York (April 1774). QUARTERING ACT under the law, colonists had to provide housing, candles, bedding, and beverages to British soldiers stationed in the colonies. In American colonial history, the British parliament provision (actually an amendment to the annual Mutiny Act) requiring colonial authorities to provide food, drink, quarters, fuel, and transportation to British forces stationed in their towns or villages. This act was passed primarily in response to greatly increased empire defense costs in America following the French and Indian War and Pontiac's War. Like the Stamp act of the same year, it also was an assertion of British authority over the colonies, in disregard of the fact that troop financing had been exercised for 150 years by representative provincial assemblies rather than by the Parliament in London. The act was particularly resented in New York, where the largest number of reserves were quartered, and outward defiance led directly to the Suspending Act as part of the Townshend legislation of 1767. After considerable tumult, the Quartering Act was allowed to expire in 1770. An additional quartering stipulation was included in the Intolerable Acts of 1774. TOWNSHEND ACT taxes goods such as glass, paper, silk, lead, and tea. Also set up new ways to collect taxes. In U.S. colonial history, series of four acts passed by the British Parliament in an attempt to assert what it considered to be its historic right of colonial authority through suspension of a recalcitrant representative assemble and through strict collection provisions of additional revenue duties. The British-American colonists named them after Charles Townshend show sponsored them. The Suspending Act prohibited the New York Assembly form conducting any further business until it complied with the financial requirements of the Quartering Act (1765) for the expenses of British troops stationed there. The second act often called the Townshend duties, imposed for the second time in history direct revenue duties, payable at colonial ports, on lead, glass, paper, and tea. The third act established strict and often arbitrary machinery of customs collection in the American Colonies, including additional officers, searchers, spies, coast guard vessels, search warrants, writs of assistance, and Board of Customs Commissioners at Boston, all to be financed out of customs revenues. The fourth Towndhend Act lifted commercial duties on tea, allowing it to be exported to the Colonies free of all British taxes. The acts posed an immediate threat to established traditions of colonial self-government, especially the practice of taxation through representative provincial assemblies. They were resisted everywhere with verbal agitation and physical violence, deliberate evasion of duties renewed nonimportation agreements among merchants, and overt acts of hostility toward British enforcement agents, especially in Boston. Such colonial tumult, coupled with the instability of frequently changing British ministries, resulted, on March 5, 1770 (the same day as the Boston Massacre), in repeal of all revenue duties except that on tea, lifting of the Quartering Act requirements, and removal of troops from Boston, which thus temporarily averted hostilities. SUGAR ACT replaced an earlier tax on molasses that had been in effect for years. In U.S. colonial history, British legislation aimed at ending the smuggling trade in sugar and molasses from the French and Dutch West Indies and at providing increased revenues to fund enlarged British Empire responsibilities following the French and Indian War. Actually a reinvigoration of the largely ineffective Molasses Act of 1733, the Sugar Act provided for strong customs enforcement of the duties levied on refined sugar and molasses imported into the colonies from non-British sources in the Caribbean. The Act thus granted a virtual monopoly of the American market to British West Indies sugar Planters. Early colonial protests at these duties were ended when the tax was lowered two years later. The Protected price of British sugar actually benefited New England distillers, though they did not appreciate it. More objectionable to the colonist were the stricter bonding regulations for shipmasters, whose cargoes were subject to seizure and confiscation by British customs commissioners and who were placed under the authority of the Vice-Admiralty Court in distant Nova Scotia if they violated the trade rules or failed to pay duties. As a result of this act, the earlier clandestine trade in foreign sugar, and thus much colonial maritime commerce, were severely hampered. STAMP ACT this law put a tax on legal documents such as wills, diplomas, and marriage papers. In U.S. colonial history, the British parliamentary attempt to raise revenue through direct taxation of all colonial commercial and legal papers, and newspapers, pamphlets, cards, almanacs, and dice. The devastating effect of Pontiac's War (1763-64) an colonial frontier settlements added to the enormous new defense burdens resulting from Great Britain's victory (1763) in the French and Indian War. The British chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir George Grenville, hoped to meet at least half of these costs by the combined revenues of the Sugar Act (1764) and the Stamp Act, a common revenue device in England. Completely unexpected was the avalanche of protest form the colonists, who effectively nullified the Stamp Act by outright refusal to use the stamps as well as by riots, stamp burning, and intimidation of colonial stamp distributors. Colonists passionately upheld their rights as Englishmen to taxed only by their own consent through their own representative assemblies, as had been the practice for a century and a half. In addition to nonimportation agreements among colonial merchants, the Stamp Act Congress was convened in New York (October 1765) by moderate representative of nine colonies to frame resolution of "rights and grievances" and to petition the king and Parliament for repeal of the objectionable measures. Bowing chiefly to pressure (in the form of a flood of petitions of repeal) from British merchants and manufacturers whose colonial exports had been curtailed, Parliament, largely against the wishes of the House of Lords, repealed the act in early 1766. Simultaneously, however, Parliament issued the Declaratory Act, which reasserted its right of direct taxation anywhere within the empire, "in all cases whatsoever." The Protest throughout the Colonies against the Stamp Act contributed much to the spirit and organization of unity that was a necessary prelude to the struggle for independence a decade later. INTOLERABLE ACT laws passed by Parliament in 1774 to punish colonists in Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party. In U.S. colonial history, collective name of four punitive measures enacted by the British Parliament in retaliation for acts of colonial defiance, together with the Quebec Act establishing a new administration for the territory ceded to Britain after the French and Indian War (1754-63). Angered by the Boston Tea Party (1773), the British government passed the Boston Port Bill, closing that city's harbor until restitution was made for the destroyed tea. Second, the Massachusetts Government Act abrogated the colony's charter of 1691, reducing it to the level of a crown colony, substituting a military government under Gen. Thomas Gage, and forbidding town meetings without approval. The third, the Administration of Justice Act, was aimed at protecting British officials charged with capital offenses during law enforcement by allowing them to go to England or another colony for trial. The fourth Coercive Act included new arrangements for housing British troops in occupied American dwellings, thus reviving the indignation that surrounded the earlier Quartering Act, which had been allowed to expire in 1770. The Intolerable Acts represented an attempt to reimpose strict British control, but after 10 years of vacillation, the decision to be firm had come too late. Rather than cowing Massachusetts and separating it from the other colonies, the oppressive measures became the justification for convening the First Continental Congress later in that same year of 1774. The Boston Tea Party The Boston Tea Party was a raid by American colonists on British ships in Boston Harbor. It took place on December 16, 1773. A group of citizens disguised as Indians, armed with tomahawks threw the contents of 342 chests of tea into the bay. This incident was one of many which stirred up bad feelings between the colonists and the British Government and soon led to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. The raid of American colonists that attacked the ships all began when the people of Massachusetts were angry over a tax which had been placed by the British Parliament on tea coming into the colonies. Though some time ships came into the harbor loaded with highly taxed tea. Because ships carrying cargoes of tea arrived in Boston Harbor continuously, the colonists called town meetings and came up with resolutions to stop the importation. The resolutions urged Governor Thomas Hutchinson to send back the ships and his refusal led to the Boston Tea Party. Boston Massacre The Boston massacre was no massacre at all, but a Boston mob and a squad of British soldiers. The riot took place on March 5, 1770. It was called a "massacre" because several colonists were killed and several others were wounded. Here is the story as Paul Revere tells it. "Twenty-one days before, on the night of March 5, 1770, five men had been shot to death in Boston by British soldiers participating in the event known as the Boston Massacre. A mob of men and boys taunted a sentry guard standing outside of the city's costume house. When other British soldiers came to the sentry's support, a free for all ensued and shots were fired into the crowd. Four died on the spot and a fifth died 4 days later. Capt. Preston and six of his men were arrested for murder, but later were acquitted through the efforts of attorneys Robert Auchmuty, John Adams, and Josiah Quincy who took their defense to ensure a fair trial. Later two other soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter." This was one of the reasons we had the American Revolution. Common Sense Common Sense was written by Thomas Paine and published in January of 1776. This document was one of many revolutionary pamphlets that was famous during that time. It advocated complete independence of Britain and it followed the natural rights philosophy of John Locke, justifying independence as the will of the people and revolution as a device for bring happiness. These words inspired the colonists and prepared them for the Declaration of Independence, although the thoughts were not original. Benjamin Rush, the Philadelphia physician, encourages Paine, while Paine was writing the pamphlet. Rush read the manuscript, secured the criticism of Benjamin Franklin, suggested the Title, and arranged for its anonymous publication by Robert Bell of Philadelphia. Common Sense was an immediate success. Paine estimated that not less than one hundred thousand copies were run off, and he bragged that the pamphlet's popularity was beyond anything since the invention of printing. Everywhere it aroused discussion about monarchy, the origin of government, English constitution ideas, and independence. Common Sense traces the origin of government to a human desire to restrain lawlessness. But government at its best is, like dress, "the badge of lost innocence." It can be diverted to corrupt purposes by the people who created it. Therefore, the simpler the government, the easier it is for the people to discover its weakness and make the necessary adjustments. In Britain "it is wholly owing to the people, and not to the constitution of the government, that the crown is not as oppressive as in Turkey. The monarchy, Paine asserted, had corrupted virtue, impoverished the nation, weakened the voice of Parliament, and poisoned people's minds. The royal brute of Britain had usurped the rightful place of law. Paine argued that the political connection with England was both unnatural and harmful to Americans. Reconciliation would cause "more calamities" than it would bring benefits. The welfare of America, as well as its destiny, in Paine's view, demanded steps toward immediate independence. OLIVE BRANCH PETITION The Olive Branch Petition was a document that declared the colonists' loyalty to the British king. This document was one of the last attempts to make peace prior to the revolution. The petition also states that the colonists wanted the Intolerable Acts repelled. King George III rejected the petition and the colonists had no other choice but to revolt. DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE In 1776, the second Continental Congress chose Thomas Jefferson to draft the Declaration of Independence. When Jefferson was done with a rough copy, he gave it to his subcommittee, which included Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, for their approval. It only took seventeen days before the copy was presented to Congress with the entire subcommittee's approval. One by one, the representatives signed the document, and on July 4th, made it official. Even though independence was declared on July 4th, it took several days for the news to reach all the colonists. Although the revolution would last until 1783, the United States was free from British rule. The Declaration of Independence is a document made up of three parts; Introduction and opening statements, wrongs done by the king, and colonists declare independence. The introduction and opening statements features this famous saying: "We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." This sentence was the topic for debate during the early and mid-1800s surrounding the slavery issue. The second part lists actions by the king that the colonists considered wrong. It is a long list that takes up most of the space in the Declaration of Independence. Part three is a small paragraph where the colonists actually declare independence. Next to the Constitution, Thomas Jefferson's document was and still is the most influential document in American history.