Executive Excess v. Judicial Process: American

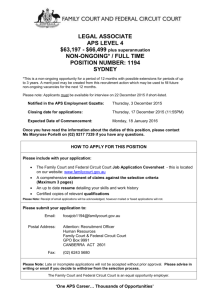

advertisement