08.II THE NEW CONSTITUTION| HOW DID Americans differ in their

advertisement

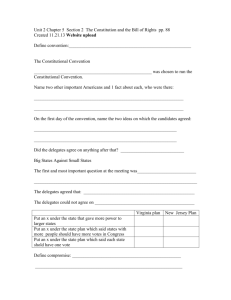

08.II THE NEW CONSTITUTION| HOW DID Americans differ in their views of the new Constitution, and how were those differences reflected in the struggle to achieve ratification? In late May 1787, fifty-five men from twelve states (the radical government of Rhode Island refused to send a delegation) assembled at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia. A number of prominent men were missing. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were serving as ambassadors in Europe. Patrick Henry of Virginia declared that he “smelt a rat” and stayed home. But most of America’s best-known political leaders were present: George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, George Mason, Robert Morris. Twenty-nine were college educated, thirty-four were lawyers, twenty-four had served in Congress, and twenty-one were veteran officers of the Revolution. At least nineteen owned slaves. Others were land speculators and merchants. But there were no ordinary farmers or artisans present, and of course, no women, African Americans, or Indians. The Constitution was framed by white men who represented America’s social and economic elite. These men were patriots, and most were republicans, committed to the idea that government must rest on the consent of the governed. But they were not democrats. They believed that the country already suffered from too much democracy. They feared that ordinary people, if given ready access to power, would enact policies against the interests of the privileged classes, and thus the nation as a whole. The specter of Shays’ Rebellion hung over the proceedings. 1. The Constitutional Convention On their first day of work, the delegates agreed to vote by states, as was the custom of Congress. They chose Washington to chair the meeting, and to ensure candid debate they decided to keep their sessions secret, although James Madison, a young Virginian with a profound knowledge of history and political philosophy, took voluminous notes that serve as our record of what transpired. Madison was instrumental in working with his fellow Virginians to draft what became known as the Virginia Plan. It was presented to the convention shortly after it convened, and it set the agenda. The Virginia Plan proposed scrapping the Articles of Confederation altogether in favor of a “consolidated government” with the power to tax and to enforce its laws directly, rather than by acting through the states. “A spirit of locality,” Madison declared, was in the process of destroying “the aggregate interests of the community,” by which he meant the great community of the nation. The Virginia Plan would have reduced the states to little more than administrative institutions, something like counties. According to its terms, representation in the bicameral national legislature would be based on population districts. The members of the House of Representatives would be elected by popular vote, but senators chosen indirectly by state legislators so they might be insulated from democratic pressure. The Senate would lead, controlling foreign affairs and the appointment of officials. An appointed chief executive and a national judiciary would together form a Council of Revision having the power to veto both national and state legislation. The main opposition to the Virginia Plan came from the delegates of the small states who feared being swallowed up by the large ones. After two weeks of debate, William Paterson of New Jersey introduced an alternative, a set of “purely federal” principles that became known as the New Jersey Plan. This plan also proposed increasing the powers of the central government, but retained a single-house Congress in which the states were equally represented. After much debate and a series of votes that split the convention down the middle, the delegates finally agreed to what has been termed the Great Compromise: representation proportional to population in the House and equal representation by states in the Senate. The compromise allowed the creation of a strong national government while still providing an important role for the states. Part of this agreement was a second, fundamental compromise that brought together the delegates from North and South. As James Madison wrote, “The real difference of interests lay, not between the large and small but between the northern and southern states. The institution of slavery and its consequences formed the line of discrimination.” Southern delegates wanted slavery protected by the central government, the northern delegates wanted a central government with the power to regulate commerce, and this formed the basis of the compromise. To boost their power, southerners wanted slaves included in the population census for the purpose of determining proportional representation, but wanted them excluded when it came to apportioning taxes. In exchange for southern support for the “commerce clause” northerners agreed to count five slaves as the equivalent of three freemen—the “three-fifths rule.” Furthermore, the representatives of South Carolina and Georgia demanded protection for the slave trade, and after bitter debate, the delegates included a provision preventing any federal restriction on the importation of slaves for twenty years. Another article legitimized the return of fugitive slaves Out of Many, 6e | Page 1 of 3 from free states. The word “slave” was nowhere used in the text of the Constitution (the writers employed phrases such as “persons held to labor”), but these provisions amounted to national guarantees for the preservation of southern slavery. Although a minority of delegates were opposed to slavery, and regretted having to give in on this issue, they agreed with Madison, who wrote that “great as the evil is, a dismemberment of the union would be worse.” There was still much to decide regarding the other branches of government. Madison’s Council of Revision was scratched in favor of a strong federal judiciary with the implicit power to declare unconstitutional acts of Congress. There were demands for a powerful chief executive, and Alexander Hamilton went on record that the executive should be appointed for life, raising fears that the office might prove to be, in the words of Edmund Randolph of Virginia, “the fetus of monarchy.” But there was considerable support for a president with veto power to check the legislature. To keep the president independent of Congress, the delegates decided he should be elected: but fearing that ordinary voters could never “be sufficiently informed” to select wisely, they insulated the process from popular choice by creating the Electoral College. Voters in the states would not actually vote for president. Rather, each state would select a slate of “electors” equal in number to the state’s total representation in the House and Senate. Following the general election, the electors in each state would meet to cast their ballots and elect the president. In early September, the delegates turned their rough draft of the Constitution over to a Committee of Style, which shaped it into an elegant and concise document providing the general principles and basic framework of government. But Madison, known to later generations as “the Father of the Constitution,” was gloomy, believing that the revisions of his original plan doomed the Union to the kind of inaction that had characterized government under the Articles of Confederation. It was left for Franklin to make the final speech to the convention. “Can a perfect production be expected?” he asked. “I consent, Sir, to this Constitution, because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best.” The delegates voted their approval on September 17, 1787, and transmitted the document to Congress, agreeing that it would become operative after ratification by nine states. Despite some congressmen who were outraged that the convention had exceeded its charge of simply modifying the Articles of Confederation, Congress called for a special ratifying convention in each of the states. 2. Ratifying the New Constitution The supporters of the new Constitution immediately adopted the name Federalists to describe themselves. Their outraged opponents objected that the existing Confederation already provided for a “federal” government of balanced power between the states and the Union, and that the Constitution would replace it with a “national” government. But in this, as in much of the subsequent process of ratification, the Federalists (or nationalists) grabbed the initiative, and their opponents had to content themselves with the label Anti-Federalists. Mercy Otis Warren, a leading critic of the new Constitution, commented on the dilemma in which the Anti-Federalists found themselves. “On the one hand,” she wrote, “we stand in need of a strong federal government, founded on principles that will support the prosperity and union of the colonies. On the other, we have struggled for liberty and made costly sacrifices at her shrine and there are still many among us who revere her name too much to relinquish, beyond a certain medium, the rights of man for the dignity of government.” The critics of the Constitution were by no means a unified group. Because most of them were localists, they represented a variety of social and regional interests. Rufus King, who had been a delegate to the convention from Massachusetts, wrote James Madison that the opposition in his state arose from the opinion “that the System is the production of the Rich and ambitious, . . . and that the consequence will be the establishment of two Orders in Society, one comprehending the Opulent and Great, the other the poor and illiterate.” Most Anti-Federalists believed that the Constitution granted far too much power to the central government, weakening the autonomy of communities and states. As local governments “will always possess a better representation of the feelings and interests of the people at large,” one critic wrote, “it is obvious that these powers can be deposited with much greater safety with the state than the general government.” All the great political thinkers of the eighteenth century had argued that a republican form of government could work only for small countries. As French philosopher Montesquieu had observed, “In an extensive republic, the public good is sacrificed to a thousand private views.” But in The Federalist, a brilliant series of essays in defense of the new Constitution written in 1787 and 1788 by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, Madison stood Montesquieu’s assumption on its head. Rhode Island, he argued, had demonstrated that the rights of property might not be protected in even the smallest of states. Asserting that “the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property,” Madison concluded that the best Out of Many, 6e | Page 2 of 3 way to control such factions was to “extend the sphere” of government. That way, he continued, “you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or, if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength and to act in unison with each other.” Rather than a disability, Madison argued, great size would be an advantage: interests would be so diverse that no single faction would be able to gain control of the state, threatening the freedoms of others. It is doubtful whether Madison’s sophisticated argument, or the arguments of the Anti-Federalists for that matter, made much of a difference in the popular voting in the states to select delegates for the state ratification conventions. The alignment of forces generally followed the lines laid down during the fights over economic issues in the years since the Revolution. Consider Pennsylvania, the first state to convene a ratification convention, in November 1787. Forty-eight percent of the Anti-Federalist delegates to the convention were farmers. By contrast, 54 percent of the Federalists were merchants, manufacturers, large landowners, or professionals. What tipped the Pennsylvania convention in favor of the Constitution was the wide support the document enjoyed among artisans and commercial farmers, who saw their interests tied to the growth of a commercial society. As one observer pointed out, “The counties nearest [navigable waters] were in favor of it generally, those more remote, in opposition.” Similar agrarian-localist and commercial-cosmopolitan alignments characterized most of the states. The most critical convention took place in Massachusetts in early 1788. Five states—Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut—had already voted to ratify, but the states with the strongest Anti-Federalist movements had yet to convene. If the Constitution lost in Massachusetts, its fate would be in great danger. At the convention, Massachusetts opponents of ratification—which included the supporters of Shays’ Rebellion— enjoyed a small majority. But several important Anti-Federalist leaders, including Governor John Hancock and Revolutionary leader Samuel Adams, were swayed by the enthusiastic support for the Constitution among Boston’s townspeople. On February 16, the convention voted narrowly in favor of ratification. To no one’s surprise, Rhode Island rejected the Constitution in March, but Maryland and South Carolina approved it in April and May. On June 21, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify. New York, Virginia, and North Carolina were left with the decision of whether to join the new Union. AntiFederalist support was strong in each of these states. North Carolina voted to reject. (It did not join the Union until the next year, followed by a still reluctant Rhode Island in 1790.) In New York, the delegates were moved to vote their support by a threat from New York City to secede from the state and join the Union separately if the state convention failed to ratify. The Virginia convention was almost evenly divided, but promises to amend the Constitution to protect the people from the potential abuses of the federal government persuaded enough delegates to produce a victory for the Constitution. The promise of a Bill of Rights was important in the ratification vote of five of the states. 3. The Bill of Rights The Constitutional Convention had considered a bill of rights patterned on the declarations of rights in the state constitutions (see Chapter 7), but then rejected it as superfluous. But Anti-Federalist delegates in numerous state ratification conventions had proposed a grab bag of over 200 potential amendments protecting the rights of the people against the power of the central government. In June 1789, James Madison, elected to the first Congress as a representative from Virginia, set about transforming them into a coherent series of proposals. Congress passed twelve and sent them to the states, and ten survived the ratification process to become the Bill of Rights in 1791. The First Amendment prohibited Congress from establishing an official religion and provided for the freedom of assembly. It also ensured freedom of speech, a free press, and the right of petition. The other amendments guaranteed the right to bear arms, limit the government’s power to quarter troops in private homes, and restrain the government from unreasonable searches or seizures; they assured the people their legal rights under the common law, including the prohibition of double jeopardy, the right not to be compelled to testify against oneself, and due process of law before life, liberty, or property can be taken away. Finally, the unenumerated rights of the people were protected, and the powers not delegated to the federal government were reserved to the states. The first ten amendments to the Constitution have been a restraining influence on the growth of government power over American citizens. Their provisions have become an admired aspect of the American political tradition throughout the world. The Bill of Rights is the most important constitutional legacy of the Anti-Federalists. Out of Many, 6e | Page 3 of 3