What Is Science? Jane Goodall is best known for studying

Lupro 1

What Is Science?

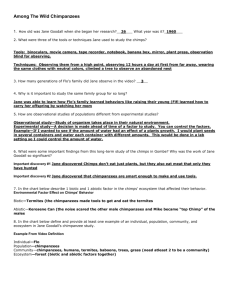

Jane Goodall is best known for studying chimpanzees in Africa, but like most people, she is a multi-faceted character. She is also a poet, a student, an environmentalist, and an activist, championing for the rights of those without voices of their own. Her ideas of science come from her observations in the jungles of Gombe, but also from her life, from her experiences. She uses her observations to make inferences about greater issues in the world. She connects what she’s learned about chimpanzees to humans; our DNA and temperaments are remarkably similar. She has used science to make a difference in this world. The dictionary defines science as

“systematic knowledge of the physical or material world gained through observation and experimentation,” (Dictionary.com) and while this definition may be sufficient for a dictionary,

Science itself is much more complex than this simple explanation.

Like Goodall, I was a naturally curious child, always eager to read a book or discover something new in my surroundings. I remember when I was very young, turning over every rock in our garden to find pill bugs or “roly polies,” as my brother and I called them. We liked to watch them roll into their tight little balls and then see what we could do to entice them to unravel themselves in our hands. In her book, Reason for Hope, Goodall says, “I loved being outside, playing in the secret places in the garden, learning about nature. My love of living things was encouraged, so that from the beginning I was able to develop that sense of wonder, of awe…” (Goodall & Berman, 1999, p. 3). These are the beginnings of science, observations.

I used to think that science was everything, that it was everything in the world that I could see and couldn’t see; that I could touch and couldn’t touch. I’ve since grasped that it is much more precise than that. Science is what you do with the observations, how you use that

Lupro 2 information to further your understanding. Simply the act of observing is not scientific, but applying what you’ve observed and employing it to discover the whys and the hows of what you’re observing. Why does something behave in a particular way and how does it do that?

Observation is merely the first step in that process.

Looking back, I don’t really remember much of anything related to science before high school, especially in elementary school. I know it was there and I know I had to have learned something in those ten years, but I couldn’t tell you just what. I remember learning about the density of water and things sinking or floating and in the 5 th

or 6 th

grade and I vaguely remember learning about ecosystems but this is probably only memorable because I had tangible souvenirs; snails that came home with me and lived in my room for about two weeks until I got tired of them and released them near a pond, as per instructions of my teacher.

Goodall began perfecting her scientific process early in life, “roaming the cliffs that rose from the seashore…There were squirrels and all manner of birds and insects. And the freedom of it!” (Goodall & Berman, 1999, pg. 18). She was a natural observer, waiting for a weasel or squirrel or fox to appear in their natural habitat and it was this very act that prepared her for her life’s work in Gombe.

Similar to Goodall, I have found that I learn much better by being able to observe the lessons I am supposed to be learning. Touching things and being involved, or watching them in action is a much more effective method of teaching, rather than simply reading a text book. The things I learned outside of school have been much more memorable and probably, helpful than those I learned in the classroom. We, both my parents and I or with my classes, took field trips to the Ann Arbor Hands-On Museum, where we learned about light and how it works, along with

the difference between reflection and refraction; and to COSI (the Center Of Science and

Lupro 3

Industry), in Ohio, where I rode a high wire bicycle, sure I was going to fall, but in fact, I learned about how gravity works and made it safely across. In 6 th

grade, our class also attended a five day science camp, where we investigated (and tasted) local plants, learned about Michigan’s native animals and also learned the benefits of recycling and composting our waste.

Observation is the first step of science, but it’s what comes after observation that makes it scientific. In science, you must take your observations and find out what they are telling you.

Use what you’ve seen and what you know to make an inference, use that inference to make a hypothesis. Predict what you think might happen if you change something or if you observe your subject for a particular period of time.

Unlike Goodall, I was not and am not now particularly drawn to working with animals, although given the chance, I would eagerly work with chimpanzees. I can, however, relate to her reasoning for working with the chimps. She sought to connect the behaviors and the biology of the chimpanzees with the behaviors and the biology of man, for they are our closest relative by

DNA, differing only by a little over one percent (Goodall & Berman, 1999, p. 53). She sought to connect her studies with the outside world, transcending chimps and applying what she observed to a larger picture. I often find myself thinking about how I can take what I’ve learned and observed and experienced and apply it in my future classroom; how I can teach science in a memorable and tangible way that will affect students in a positive manner and help them comprehend what science is.

In high school, I had a science class for all four years, starting with a 9 th

grade science class, meant to gauge what you had learned so far and set up a foundation for what you would

learn in future classes. The next year, I had Biology 1, where I remember dissecting frogs,

Lupro 4 growing flowers and vegetables in the green house, memorizing bones, learning about genetics and DNA, and really gaining an interest in science. After that, I took Chemistry, where I learned about the table of elements and how to measure in moles, and different types of reactions. I continued in a physics class the next year, even though I was a senior and not required to take any science classes. My teacher for this class tried to make physics relatable and we learned about how cell phones work and the physics of roller coasters. I think this was successful in making the students learn physics but also have a little fun and be interested in what we were learning and I probably didn’t appreciate this enough in the process of the class but I have come to realize its benefits now.

Instead of learning about science and the chimpanzees from a book, from thousands of miles away, or from a zoo, which is not remotely close to the animals’ natural habitat, Goodall took the opportunities that were offered to her to visit the jungle, to put herself into the chimps’ lives. She followed the calls of the chimps, learning their behavioral patterns and observing them from afar until she was able to gain their trust. She then states, “In order to collect good, scientific data, one is told, it is necessary to be coldly objective. You record accurately what you see and, above all, you do not permit yourself to have any empathy with your subjects.” She acknowledges that this theory is not always applicable, “Fortunately I did not know that during the early months at Gombe. A great deal of my understanding of these intelligent beings was built up just because I felt such empathy with them. Once you know why something happens, you can test your interpretations as rigorously as you like” (Goodall & Berman, 1999, pgs. 77-

78).

Lupro 5

Science is a set of skills. It is observation, making inferences, predicting outcomes, recording data and so much more. (Rezba, R. J., Sprague, C., Mcdonnough, J. T., & Matkins, J.

J., 2008). However, it is not the scientific method we so often learn in elementary school, with its set amount of steps and rigid procedures. It is malleable. You can adapt the skills and processes needed to your own specific experiments or studies and while every skill is necessary, they do not always require the same level of importance, nor are the required to be followed in a strict order.

When I was in elementary school, I made it to the school science fair from our classroom one numerous times, but I don’t remember learning anything from those experiences except that the scientific method goes: question, then hypothesis, then gather materials, then perform an experiment, then collect and analyze data, and eventually form some sort of conclusion based on that data. This is not a lesson in science but rather a lesson in memorization and following directions. Even more recently, at the beginning of the Fall semester in 2010, I wrote what I thought science was in my notebook during the first weeks of my Science in the Elementary

School class and now I realize what I wrote was a result of what I had learned throughout my schooling. It wasn’t necessarily wrong but it wasn’t right in that I didn’t quite grasp the skills and processes of science. I wrote, “Science can be anything. It’s the study of living and non-living things.”

Despite the fact that most people and scientists didn’t believe in her, despite the fact that she was going into a jungle full of wild animals in an unstable country, and despite having no academic training, Goodall spent many years working with the chimpanzees of Gombe. She would climb cliffs and rocks and trees, waiting and hoping to hear the calls of the chimps or even better, to observe them. Her observations turned to inferences and eventually led to a wider study

Lupro 6 of the chimps. She, along with other scientists, transformed her observations into books and ideas about not only the chimps but about the nature of man, noting that chimps have qualities astonishingly similar to man. One day, she observed a chimp, who she named David Greybeard, using grass stems to pull termites out of the ground. This discovery redefined how the world saw man. “It had been long thought that we were the only creatures on earth that used and made tools…This ability set us apart, it was supposed from the rest of the animal kingdom” (Goodall

& Berman, 1999, pg. 67).

Not all science is going to change the world, but it should, in some way or another, explain why and how things occur the way they do. It is, in fact, knowledge gained through observation and experimenting. It is also how you gain that knowledge, what sparked the need to observe something, how you experiment, and what kind of data you collect. It’s the conclusions you come to based on your data, whether it is what you expected or not. It is, like Jane Goodall did, seeing an issue, taking your observations and applying them to something else, maybe a bigger picture or maybe just defining how something functions and why, and it is figuring out what makes your observations meaningful. After all, “it is up to us to save the world for tomorrow: it’s up to you and me” (Goodall & Berman, 1999, pg. 251).

Lupro 7

References

Goodall, J., & Berman, P. (1999). Reason For Hope . New York: Warner Book.

Rezba, R. J., Sprague, C., Mcdonnough, J. T., & Matkins, J. J. (2008). Learning and Assessing

Science Process Skills . Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company.

Science. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged . Retrieved November 28, 2010, from

Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/science