Some Design Issues for an Online Japanese Textbook

advertisement

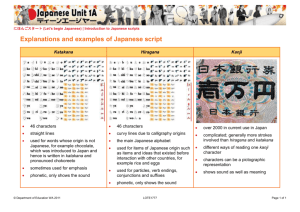

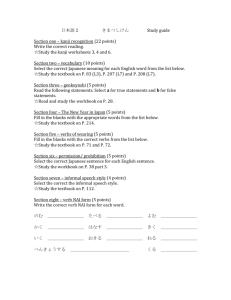

CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook Some Design Issues for an Online Japanese Textbook Noriko Nagata University of San Francisco ABSTRACT This paper discusses several design issues in the development of a new online Japanese textbook, called Robo-Sensei: Japanese Curriculum with Automated Feedback. When it is completed, the new online textbook will present a full Japanese curriculum. It extends a previously published online software program, Robo-Sensei: Personal Japanese Tutor (Nagata, 2004), which was designed as a supplement to standard, printed Japanese textbooks. The issues discussed include incorporation of natural language processing (NLP) technology, visual images, sounds, grading, modular organization, and classroom activities. Special attention is devoted in this paper to the design of a stand-alone module for teaching Japanese characters, called Kana Power. Student evaluations of the Kana Power module are discussed. Throughout the paper, the potential advantages of online versus printed textbooks are emphasized. KEYWORDS Software Design, Online Textbook, Natural Language Processing (NLP), Visual Images, Japanese Character Practice INTRODUCTION Robo-Sensei: Personal Japanese Tutor (Nagata, 2004) was designed as a supplement to standard Japanese textbooks. However, supplementary materials, no matter how valuable, require some effort to coordinate with the main curriculum of a course. The natural next step is to develop a self-contained online textbook. Robo-Sensei: Japanese Curriculum with Automated Feedback, a complete, online Japanese textbook, represents that next step. The new online textbook will cover a standard 2- or 3-year Japanese curriculum. Currently, the underlying computational engine is complete and several chapters have been created. The new online textbook will run on ordinary web browsers with both Windows and Mac OS and will be distributed through the internet or a CD-ROM. This paper discusses some design issues involved in the development of the online textbook, such as incorporation of natural language processing (NLP) technology, visual images, sounds, grading, modular organization, and classroom activities. Special attention will be devoted in this paper to the textbook’s new Kana Power package, which provides detailed instructions about kana characters, animated writing demonstrations of the characters, online flash cards, and a variety of kana exercises. Student feedback on the Kana Power program will be summarized. CALICO Journal, 27(3), p-p 460-476. © 2010 CALICO Journal 460 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Noriko Nagata DESIGN ISSUES NLP Technology A major advantage of an online textbook over a printed textbook is interactivity (Smith, 1991). A printed textbook may present a number of exercises, but it cannot respond to students’ answers; as a result, there is no interaction between the textbook and the students, and the students have to wait for the instructor’s corrections. On the other hand, an online textbook can provide immediate responses to students’ answers. Traditional multiple choice or fill-in-the-blank computer exercises determine only whether students’ answers are exactly matched with stored correct answers. Accordingly, the corresponding feedback messages are standardized and for the most part limited to notifying the student whether the answer is correct or incorrect. NLP techniques such as parsing, on the other hand, can be used to provide specific feedback to incorrect or correct input. A parser, a (usually) sentence-level language analyzer, can be designed to determine whether the input is grammatically correct. The results of the parse can be used to generate detailed messages that explain the grammatical principles violated in the learner’s sentence. NLP technology significantly enhances the level and fruitfulness of the student-textbook interactions, a major potential advantage of online textbooks over printed texts. NLPbased CALL programs have been described by a number of researchers (Sanders, 1991; Nagata, 1993; Holland, Kaplan, and Sams, 1995; Delmonte, 2003; Heift & Schulze, 2007). In addition, a recent special issue of the CALICO Journal, “On the Automatic Analysis of Learner Language” (Meurers, 2009) was devoted to this topic. The Robo-Sensei online textbook applies NLP techniques to provide extensive sentence production exercises and individualized, detailed feedback in response to learners’ grammatical errors. A full description of Robo-Sensei’s NLP system is provided in Nagata (2009). A series of empirical studies support the effectiveness of NLP-based grammatical feedback (e.g., Nagata 1993) as well as the effectiveness of production-based practice (e.g., Swain & Lapkin, 1995; DeKeyser & Sokalski, 1996; Nagata, 1998). The textbook will present various types of NLP-based exercises designed to develop learners’ production skills progressively from the lexical and phrase level to the sentence level, helping them to acquire a solid foundation in vocabulary and grammar. Also, writing tasks are integrated gradually with reading and listening tasks so that different skills develop jointly and reinforce one another. Immediate, on-going, principle-based feedback helps students to pay attention to their weaknesses throughout the curriculum until they master the target structures. Figure 1 presents one of the sentenceproduction exercises provided in Chapter 14 in the online textbook. 461 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook Figure 1 An Exercise in Robo-Sensei (Chapter 14) Visual Images Visual images such as digital photographs, video clips, and drawings provide students with a rich cultural context for course materials (see Forester, 2002). Also, authentic images from the places where the target language is spoken can enhance students’ cultural awareness and provide motivation for language learning. Printed textbooks are limited by space and cost in the number of color images they can accommodate and cannot present moving images at all. Online texts, on the other hand, have a potentially unlimited capacity to present bright, colorful, authentic images and videos. The Robo-Sensei online textbook includes abundant cultural photographs and short video clips. In order to avoid copyright issues, the author and the project photographer (Kevin T. Kelly) took approximately 20,000 digital images over several visits to historical and cultural sites in Japan. For example, Chapter 14 “The Hidden Land of Master Carpenters (Comparisons)” includes 150 digital images taken in Takayama City, presenting Japanese traditional architecture and crafts (thatched farmhouses, merchant houses, a governor’s mansion, festi 462 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Noriko Nagata val floats, sake brewing, wooden mask carving, rope sandal making, etc.) from the 17th-19th century, the Edo samurai period. The large number of images allows for close shots of craft activities and architectural details that are rarely seen, even on travel websites. Sounds Unlike a printed textbook, an online textbook can directly link sounds to the text, so it is easy to integrate listening activities into the text. When students read new dialogues and vocabulary in a printed textbook, they cannot receive immediate reinforcement regarding correct pronunciation. In an online textbook, students have immediate access to correct pronunciations, and they can hear target sentences and vocabulary when their attention is at its peak. The Robo-Sensei online textbook provides auditions of the core dialogue and vocabulary items introduced in each chapter. Students can also hear the pronunciation of correct answers while doing the exercises. A number of listening tasks are provided together with reading and writing tasks. Since free audio recorders such as Audacity (http://audacity.sourceforge. net//?lang=en) are available on the web, the Robo-Sensei online textbook does not have its own sound recording system. Grading A printed text cannot grade student performance, but an online textbook can. Students can try out online activities at their own pace until they improve their scores. Several studies have supported the positive motivational effects of self-paced online activities (Nutta, 1998; Polisca, 2006; Scida & Saury 2006; Bañados, 2006). For example, Scida and Saury compared a traditional course with a hybrid course which included 2 hours of mandatory, web-based practice activities every week. They found that the average grade in the hybrid course was higher than that in the traditional course, due to the fact that most of the students in the hybrid course worked on online assignments until they achieved perfect scores even after reaching the required score level. The increased practice from the hybrid course resulted in higher achievement. The Robo-Sensei online textbook is programmed to record feedback messages students receive for their errors as well as grade their performance in exercises. In Robo-Sensei’s Tutor module, students obtain four points when they get the answer correct immediately on the first try, three points on the second try, and two points on the third try. The students are offered the “Answer” button after failing three times, but they still obtain one point for a correct answer on their fourth try. In this way, the students can closely track their own performance. The instructor can also monitor student performance and determine whether certain principles and tasks require further attention during class. Modular Organization The Robo-Sensei online textbook is based on a grammatical, functional, and situational syllabus. Following typical textbook organization, each chapter in Robo-Sensei consists of six modules: Introduction, Grammar, Dialogue, Vocabulary, Kana/Kanji, and Tutor (exercises). Students can navigate freely between the modules simply by pressing buttons at the bottom of the screen. Each module’s content is also printable in PDF for ease of reference. The first five modules focus on text and character presentations and are written in Flash, which is well suited for enhanced multimedia presentations and animations. The Tutor module is a stand 463 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook alone program that offers extensive sentence-production exercises graded by Robo-Sensei’s NLP system. The tutor is written in Java to handle complex sentence analysis and feedback generation. Figure 2 illustrates the screen image of the Introduction module. Figure 2 Introduction Module (Chapter 2) The Introduction module presents a few target sentences along with relevant photographic images and briefly states the objectives of the chapter. The PDF map button shows a map of Japan in which the locations of all cultural sites used in the textbook are marked. The Grammar button opens the Grammar module which provides detailed descriptions of the target grammatical patterns. The Dialogues button presents core dialogues in which the target grammatical patterns, new vocabulary, and new characters appear. The dialogue stories are based on the cultural theme of the chapter. The Vocabulary button presents a list of new vocabulary items introduced in the chapter. Some vocabulary items are linked to Wikipedia for further information (another advantage of online texts). The Kana button links to Robo-Sensei Kana Power (see below). Prior to Chapter 8, the button calls up the Kana module; from Chapter 8 onward, it calls up the Kanji module. The Tutor button links to Robo-Sensei’s NLP-based exercises. 464 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Noriko Nagata Classroom Activities Distance learning is the application that comes immediately to mind for an online textbook. However, the author’s classroom experience with Robo-Sensei: Personal Japanese Tutor revealed that online materials can be particularly useful in classroom situations. For example, the online textbook’s Tutor module provides production exercises that are mostly presented in conversational settings. The instructor can utilize such exercises as an occasion for in-class role playing between students. The Tutor module also includes a Pair Work section designed for practicing conversations with partners. During traditional pair work, students usually help one another correct their answers but do not necessarily succeed in formulating grammatical sentences. Some pairs easily get lost and cannot continue the exercises until the instructor assists them. With Robo-Sensei, however, pairs do not have to wait for the instructor for feedback—they can check their answers and make progress on their own, which frees the instructor to focus on higher level issues and to distribute attention more evenly across the groups to keep the activity moving. Thus, Robo-Sensei’s NLP technology can be an advantage even when the instructor is interacting with the students in a traditional classroom setting. Furthermore, individuals differ in the amount of time required to complete in-class activities, and the students who need the activities the most are the least likely to finish them on time. If classroom activities are assigned from Robo-Sensei, the students who could not finish them in class can complete them at home and submit a score sheet graded by Robo-Sensei. Kana Power A typical Japanese curriculum introduces the writing system kana (hiragana and katakana) in the first semester. An online textbook opens up many possibilities for character practice (Kunst, 1987). A number of online kana materials are available on the web. However, most of them offer only simple reading practice (typing in romaji, reading for each kana, or choosing a correct reading)1 and some present stroke order animations,2 but there is no software program with which students can systematically learn and practice everything about kana. One major design decision for the Robo-Sensei textbook was to include a comprehensive kana program that provides complete descriptions of kana characters, animated writing demonstrations of the characters, online flash cards, and a variety of kana exercises, all in one stand-alone online package. Since the kana exercises do not involve grammatical analysis, NLP technology is not employed for the Kana Power program. It is entirely written in Flash. A sophisticated writing practice tool for Japanese children, Tadashii Kanji Kakitori-kun (Kageyama, 2007), allows learners to write Japanese characters on a game console, and the software judges the quality of the characters the learner produces. Robo-Sensei Kana Power will not have that capability; a decision was made not to load the version with more specialty hardware (e.g., pressure-sensitive computer writing tablet) since it would restrict use of the program to those who have the hardware. The following sections describe each component of Kana Power. The software will be integrated in the new online textbook and can be used by anyone who needs to practice kana characters. It contains two programs, one for hiragana and the other for katakana. Both programs provide four button menus on the front page, “About Hiragana” or “About Katakana,” “Stroke Animation,” “Flash Cards,” and “Exercises.” About hiragana/about katakana The button for About Hiragana/About Katakana opens a PDF file that explains hiragana or katakana, including a brief history of the Japanese writing systems, character charts, stroke order rules, horizontal and vertical writing formats, and mnemonics. 465 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook Stroke animation The Stroke Animation button links to a page in which students can click on each character to see the character being written in a graphical animation (see Figure 3). Figure 3 Kana Power Stroke Animation Stroke order is crucial for writing Japanese characters accurately, and it is emphasized in Japanese language education. Writing characters with the proper stroke order each time also makes the characters much easier to remember. Students can stop the demonstration at any time to observe a stage of writing and then restart the demonstration. This option allows students to take their time and to focus on individual challenges. Figure 3 shows an intermediate stage of the stroke demonstration for hiragana あ a. By clicking each character in the chart or the sound button, students can hear the pronunciation of the character as well. The mouth of the animated Robo-Sensei mascot (in the lower right-hand corner of the screen) phonetically imitates the pronunciation of each character to help simulate the presence of a real teacher. 466 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Noriko Nagata Flash card The Flash Card button displays the flash card front page (see Figure 4). Figure 4 Flash Cards Front Page In a regular Japanese curriculum, the teacher introduces hiragana and katakana gradually (e.g., 10 characters per week). As seen in Figure 4, the tabs attached to the hiragana table enable learners to choose a stack of hiragana characters and to extend the stack according to their own learning pace. For example, for the first week, students can select the tab for the stack of hiragana あ a through こ ko. For the second week, they can select the tab for the stack of hiragana さ sa through と to, or, if they want to include the previous stack together, they can choose the tab for the stack of hiragana あ a through と to, and so forth. 467 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook Figure 5 illustrates one of the flash cards, な. Figure 5 Flash Card な na Cards are presented randomly, so every time students go through the stack, the cards appear in a different order. While practicing hiragana reading, students can make a personal flash-card stack for troublesome hiragana. That is, by clicking the add card icon (next to the sound icon), students can add the currently presented problem hiragana to “My Stack.” Then, after finishing all hiragana in the full stack, students can click My Stack to work on only the hiragana characters they had trouble with. Students can hear the correct pronunciation of the character immediately rather than (as with a paper flash card) flipping the card over and checking a written romanization. By clicking the sound button, students can hear the pronunciation of the presented character and see it spelled in roman characters as well. A stop watch is included so that students can gauge their progress. 468 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Noriko Nagata Exercises Like the flash card front page, tags are provided to choose a character set that students wish to practice. There are four types of exercises: “Reading,” “Identifying,” “Stroke Order,” and “Writing.” All exercises are graded, and the scores are presented at the end of the exercises. In every exercise, the character’s reading is sounded when the student’s answer is correct. Reading. Learners are asked to type in the reading (romanization) of each character. Being able to romanize characters accurately will also help them to learn Japanese typing since the standard computer interface for typing Japanese characters uses a Roman-alphabet keyboard and then converts the Roman characters into Japanese characters on the screen. The exercises start with reading a single character and move to reading a word. Figure 6 illustrates one of the reading exercises. Feedback messages for missing long vowels and double consonants, which are common errors, are also provided. Figure 6 Reading Exercise 469 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook Identifying. Quite a few characters in hiragana or in katakana are often conflated and need to receive special attention. The Identifying exercise presents two characters that look similar and asks students to choose the correct one. Figure 7 shows katakana シ shi and ツ tsu and asks students to mark shi. This kind of exercise is not commonly offered in kana practice but is very useful. Figure 8 presents a score summary at the end of the Identifying exercises (the selected stack is for ア a through ヨ yo.) Figure 7 Identifying Exercise 470 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Noriko Nagata Figure 8 Identifying Exercise Score Summary Stroke order. This exercise draws students’ attention to stroke order and lets them trace correct stroke order. Students are asked to drag each stroke number to its starting position in the character (see Figure 9). When they answer correctly or miss the correct answer three times, the button for the stroke animation (next to the check mark icon) appears so that they can see the character being written. The Rules icon links to a PDF file in which stroke order rules are explained in detail. 471 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook Figure 9 Stroke Order Exercise Writing. This exercise provides a Roman character cue for students to write down a corresponding character on their worksheet. The worksheet is attached in a PDF file. By clicking the check button, they can compare their writing with the correct answer and can see the stroke order animation as well. The exercises start with writing single characters and move on to full words. QUESTIONNAIRE RESULTS ON KANA POWER Kana Power was beta-tested in a first semester university Japanese course in spring 2009. After the hiragana program was used, a questionnaire was administered to 18 students in the course. Students responded to the questionnaire items on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The following discusses some focal points based on the questionnaire results. 472 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Noriko Nagata 1. The stroke animations were considered helpful (M = 4.6, SD = 0.6) as well as the sounds accompanying the stroke animations (M = 4.7, SD = 0.6). 2. The students also indicated that flash cards were helpful for practicing reading (M = 4.7, SD = 0.6); the character font was clear (M = 4.7, SD = 0.6), the character size was large enough (M = 4.8, SD = 0.5), and the My Stack feature was helpful for reviewing difficult hiragana (M = 4.6, SD = 0.7). 3. After all hiragana were introduced, the students took a quiz using the online flash cards. Ninety-one percent of the students earned perfect or near perfect scores (above 90%) in reading all hiragana randomly presented by the online flash cards. Although the flash cards have a timer function, the quiz did not include students’ reading speed as a score point. That may explain the relative low rating of the timer’s helpfulness in creasing the speed of their hiragana reading (M = 4.1, SD = 0.8). It is suggested that reading speed should be credited as part of the hiragana recognition quiz. Then, students may be more motivated to utilize the timer and improve their reading speed. 4. The students were asked if they found the online flash card program more useful than traditional printed index cards (M = 4.2, SD = 1.0). Seventy-two percent of the students considered the online flash cards to be more useful than traditional printed cards (Out of 18 students, nine rated the online flash cards “5” and four rated them “4”). However, the other students did not indicate a strong preference for online flash cards. In the next survey, we will ask why students prefer printed flash cards to the online ones. In any event, online and traditional paper printed cards are not exclusive. Students can be encouraged to use both: paper flash cards are easy to carry anywhere, and such portability and convenience is still an advantage. 5. The students considered the Reading, Identification, and Stroke Order exercises to be helpful (M = 4.7, SD = 0.6; M = 4.6, SD = 0.8; M = 4.6, SD = 0.8; respectively). 6. In the online Writing exercises, the students were asked to print a PDF file (worksheet) and to write by hand individual characters or words prompted by the online exercises. In each exercise, both the correct answer and the button to see the stroke animation are presented, so students can check the correctness of their writing. They were asked to submit the worksheets as homework to the instructor. Eighty percent of the students utilized the online Writing exercises to work on the worksheet assignments. The instructor found fewer errors in the submitted worksheets than in those submitted in the previous semester when the worksheet assignments were not accompanied by the online Writing exercises. This finding suggests that being able to correct answers with the online exercises may improve students’ homework performance, but a more systematic empirical study is required. 7. The instructor used the stroke animation feature (see Figure 3 above) when introducing new hiragana. In addition, 80% of the students utilized the stroke animations while doing the Stroke Order exercises, and 60% while doing the Writing exercises. That suggests that it is important to include exercises related to the stroke order to encourage students to pay attention to the stroke order and to increase their opportunities to observe stroke demonstrations. 8. The students were presented with their performance scores at the end of the Reading, Identification, and Stroke Order exercises. The students considered the exercise grading system good (M = 4.7, SD = 0.5) and concluded that the presentation of the scores motivated them to improve their performance (M = 4.8, SD = 0.4). The stu- 473 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook dents were asked to do assigned exercises weekly, to print out their scores, and to submit the score sheet. The students were not asked to report how many times they tried to improve their scores, but the instructor observed that most of the students repeated the exercises until they could obtain scores higher than 80%. 9. Regarding the audio feature of the exercises, the students indicated that the audio pronunciations were clear (M = 4.8, SD = 0.4) and being able to hear correct pronunciations was helpful (M = 4.8, SD = 0.5). 10. The format and the content of each exercise type were considered good (M = 4.6, SD = 0.7 and M = 4.7, SD = 0.6; respectively). 11. Overall, the students rated the usefulness of Kana Power positively. The software helped them concentrate on studying hiragana (M = 4.7, SD = 0.6), they would want to practice Japanese characters with this kind of software on a regular basis (M = 4.6, SD = 0.8), and the software was useful for practice outside the classroom (M = 4.6, SD = 0.7). In the future, it would be interesting to investigate the relative effectiveness of the online kana software and the traditional paper-and-pencil kana workbook in acquisition of kana stroke orders, shapes, pronunciations, and quick reading. CONCLUSION This article summarizes some design issues for a new online textbook, Robo-Sensei: Japanese Curriculum with Automated Feedback. These issues include incorporation of natural language processing, visual images, sounds, grading, modular organization, and classroom activities. Particular attention was devoted to the Kana Power module of the textbook, which is a standalone, comprehensive package for learning and practicing Japanese characters. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I received full-time funding from the University of San Francisco (USF) for my sabbatical year in 2006-2007 to develop Robo-Sensei: Japanese Curriculum with Automated Feedback, along with university faculty travel funds to gather cultural materials and digital images of Japan over three summers. The project consultant, Kevin T. Kelly, assisted with graphical design, onsite photography in Japan, and the production of cultural notes. Japanese instructors (Kyoko Suda, Reiko Itoh, Yumi Moriguchi, and Yoko Otomi) and USF students helped with lesson checking and in-classroom testing. NOTES The following sites provide kana reading practice: Real Kana (http://www.realkana.com), Nihongoup (http://www.tofugu.com/2009/06/05/practice-kana-kanji-and-particles-with-nihongoup), Kongregate Kana Practice (http://www.kongregate.com/games/Giallo/kana-practice), Japanese Kana Quizzes (http:// www.manythings.org/japanese), ひらがな・カタカナ(http://www.okayama-u.ac.jp/user/int/study/gaku syu/index.html), Usagi-Chan’s Genki Resource Page (http://www.csus.edu/indiv/s/sheaa/projects/gen ki/hiragana-timer.html), Kana Flashcards, (http://www.zompist.com/flash.html?key=a), and Kana Flash Cards (http://www.manuelsweb.com/nippon.htm). 1 The following sites provide kana stroke order animations: HIRAGANA (http://genki.japantimes.co.jp/ self/site/hiragana/hiragana.html) and Usagi-Chan’s Genki Resource Page (http://www.csus.edu/indiv/s/ sheaa/projects/genki/hiragana.html). 2 474 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Noriko Nagata REFERENCES Bañados, E. (2006). A blended-learning pedagogical model for teaching and learning EFL successfully through an online interactive multimedia environment. CALICO Journal, 23, 533-550. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page.php?id=5 Delmonte, R. (2003). Linguistic knowledge and reasoning for error diagnosis and feedback generation. CALICO Journal, 20, 513-532. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page.php?id=5 DeKeyser, R., & Sokalski, K. (1996). The differential role of comprehension and production practice. Language Learning, 46, 613-642. Forester, L. (2002). Implications of research on human memory for CALL design. CALICO Journal, 20, 99-126. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page.php?id=5 Heift, T., & Schulze, M. (2007). Errors and intelligence in computer-assisted language learning: Parsers and pedagogues. New York: Routledge. Holland, V. M., Kaplan, J. D., & Sams, M. R. (1995). Intelligent language tutors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Kageyama, H. (2007). Tadashii Kanji Kakitori-kun (正しい漢字かきとりくん ). Tokyo: Shogakukan. Kunst, R. (1987). Chinese Flashcards on computer: A CAI system for Chinese with voice, characters, and Pinyin tonal diacritics. CALICO Journal, 4, 51-57. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page. php?id=5 Meurers, D. (2009). On the automatic analysis of learner language: Introduction to the special issue. CALICO Journal, 26, 469-473. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page.php?id=5 Nagata, N. (1993). Intelligent computer feedback for second language instruction. The Modern Language Journal, 77, 330-339. Nagata, N. (1998). The relative effectiveness of production and comprehension practice in second language acquisition. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 11, 153-177. Nagata, N. (2004). ROBO-SENSEI: Personal Japanese tutor. Boston: Cheng and Tsui. Nagata, N. (2009). Robo-Sensei’s NLP-based error detection and feedback generation. CALICO Journal, 26, 562-579. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page.php?id=5 Nutta, J. (1998). Is computer-based grammar instruction as effective as teacher-directed grammar instruction for teaching L2 structures? CALICO Journal, 16, 49-62. Retrieved from https://calico. org/page.php?id=5 Polisca, E. (2006). Facilitating the learning process: An evaluation of the use and benefits of a virtual learning environment (VIE)-enhanced independent language-learning program (ILLP). CALICO Journal, 23, 499-516. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page.php?id=5 Sanders, R. (1991). Error analysis in purely syntactic parsing of free input: The example of German. CALICO Journal, 9, 72-89. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page.php?id=5 Scida, E., & Saury, R. (2006). Hybrid courses and their impact on student and classroom performance: A case study at the University of Virginia. CALICO Journal, 23, 517-532. Retrieved from https:// calico.org/page.php?id=5 Smith, G. A. (1991). Tomorrow’s foreign language textbook: Paper or silicon? CALICO Journal, 8, 5-15. Retrieved from https://calico.org/page.php?id=5 Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (1995). Problems in output and the cognitive processes they generate: A step towards second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 16, 371-391. 475 CALICO Journal, 27(3) Some Design Issues for an Onbline Japanese Textbook AUTHOR’S BIODATA Noriko Nagata is Professor and Chair of the Department of Modern and Classical Languages and Director of Japanese Studies at the University of San Francisco. Her research involves the development of natural language processing for CALL and empirical studies examining the effectiveness of various CALL features in second language acquisition. She is currently working on expanding the NLP-based software package, ROBO-SENSEI: Personal Japanese Tutor to a stand-alone online Japanese textbook. AUTHOR’S ADDRESS Noriko Nagata Department of Modern and Classical Languages University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Phone:415 422 6227 Fax: 415 422 6928 Email:nagatan@usfca.edu 476