Early US Land Disputes – Station 1

advertisement

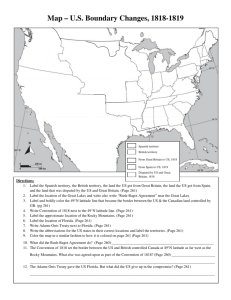

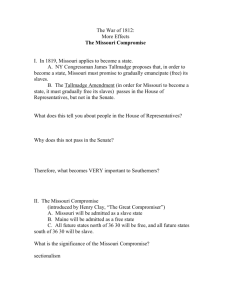

Early U.S. Land Disputes – Station 1 – Rush-Bagot Agreement/Convention of 1818 Directions: Please use the provided resources to answer the following questions regarding the Rush-Bagot Agreement/Convention of 1818. Please do not write on this sheet. Instead, please record your answers on the answer sheet that was provided to you. Step 1: Read page 298 in your textbook and answer the following questions. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. When the War of 1812 ended, what issues were still unresolved? What did the Rush-Bagot agreement accomplish? Why was the Convention of 1818 important? Why do you think the two countries did not extend the Convention of 1818 all the way to the West coast? How was the issue of the fur trade resolved with the Convention of 1818? Step 2: Read the handout on the Rush-Bagot Agreement. This handout was the actual text of the agreement. As you read through the agreement, answer the following questions. 1. What were the requirements for both sides on Lake Ontario? 2. What were the requirements for both sides on the upper lakes? 3. What were the requirements for Lake Champlain? Step 3: Using the exchange of notes handout, answer the following question. 1. In summary, what was the Canadian ambassador telling the U.S. government when he wrote them in 1946? Step 4: 1. On what date was the Convention of 1818 signed? 2. What did the Rush-Bagot agreement and the Convention of 1818 mark between the U.S. and Britain? 3. When was the Convention of 1818 renegotiated? 4. What was it called when it was renegotiated? 5. What changed in the renegotiation? Step 5: Follow the instructions on your answer sheet for filling in the map for the Rush-Bagot Agreement/Convention of 1818. Station 1 - Step 2: Rush Bagot Agreement Handout The naval force to be maintained upon the American Lakes by His Majesty and the Government of the United States shall henceforth be confined to the following vessels on each side, that is — On Lake Ontario, to one vessel not exceeding one hundred tons burden, and armed with one eighteen pound cannon. On the upper lakes, to two vessels, not exceeding like burden each, and armed with like force. On the waters of Lake Champlain, to one vessel not exceeding like burden, and armed with like force. All other armed vessels on these lakes shall be forthwith dismantled, and no other vessels of war shall be there built or armed. If either party should hereafter be desirous of annulling this stipulation, and should give notice to that effect to the other party it shall cease to be binding after the expiration of six months from the date of such notice. The naval force so to be limited shall be restricted to such services as will, in no respect, interfere with the proper duties of the armed vessels of the other party. Station 1 - Step 3: Exchange of Notes Handout The Canadian Ambassador to the United States to the Secretary of State of the United States CANADIAN EMBASSY Washington, November 18, 1946. Note 421 Sir, You will recall that the Rush-Bagot Agreement of 1817 has been the subject of discussion between our Governments on several Occasions in recent years and that notes were exchanged in 1939, 1940 and 1942 3 relating to the application and interpretation of this Agreement. It has been recognized by both our Governments that the detailed provisions of the Rush-Bagot Agreement are not applicable to present day conditions, but that as a symbol of friendly relations extending over a period of nearly one hundred and thirty years the Agreement possesses great historic importance. It is thus the spirit of the Agreement rather than its detailed provisions which serves to guide our Governments in matters relating to naval forces on the Great Lakes. Discussions have taken place in the Permanent Joint Board on Defence with regard to the stationing on the Great Lakes of naval vessels for the purpose of training naval reserve personnel. The naval authorities of both our Governments regard such a course as valuable from the point of view of naval training and the Board has recorded its opinion that such action would be consistent with the spirit of existing agreements. The Canadian Government concurs in this opinion. In order that the views of our two Governments may be placed on record, I have the honour to propose that the stationing of naval vessels on the Great Lakes for training purposes by either the Canadian Government or the United States Government shall be regarded as consistent with the spirit of the Rush-Bagot Agreement provided that full information about the number, disposition, functions and armament of such vessels shall be communicated by each Government to the other in advance of the assignment of vessels to service on the Great Lakes. If your Government concurs in this view, this note and your reply thereto shall be regarded as constituting a further interpretation of the Rush-Bagot Agreement accepted by our two Governments. Accept, Sir, the renewed assurances of my highest consideration. [signed] H. H. WRONG, Canadian Ambassador. Station 1 - Step 4: Convention of 1818 Handout The Convention of 1818 was a treaty signed in 1818 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It resolved standing boundary issues between the two nations, and allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country, otherwise known as the Columbia District of the Hudson's Bay Company. The treaty marked the United Kingdom's last permanent major loss of territory in what is now the Continental United States, while gaining it the northernmost tip of the territory of Louisiana above the 49th parallel north, known as the Milk River in present day southern Alberta and south west Saskatchewan. Britain ceded all of Rupert's Land south of the 49th parallel and west to the Rocky Mountains, including all of the Red River Colony south of that latitude. The treaty was negotiated for the U.S. by Albert Gallatin, ambassador to France, and Richard Rush, minister to the UK; and for the UK by Frederick John Robinson, Treasurer of the Royal Navy and member of the privy council, and Henry Goulburn, an undersecretary of state. The treaty was signed on October 20, 1818. Ratifications were exchanged on January 30, 1819. The Convention of 1818, along with the Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1817, marked the beginning of improved relations between the British Empire and its former colonies, and paved the way for more positive relations between the U.S. and Canada, notwithstanding that repelling U.S. invasion was a defense priority in Canada until the Second World War. Despite the relatively friendly nature of the agreement, it nevertheless resulted in a fierce struggle for control of the Oregon Country in the following two decades. The British-chartered Hudson's Bay Company, having previously established a trading network centered on Fort Vancouver on the lower Columbia River, with other forts in what is now eastern Washington and Idaho as well as on the Oregon Coast and in Puget Sound, undertook a harsh campaign to restrict encroachment by U.S. fur traders to the area. By the 1830s, with pressure in the U.S. mounting to annex the region outright, the company undertook a deliberate policy to exterminate all fur-bearing animals from the Oregon Country, in order to both maximize its remaining profit and to delay the arrival of U.S. mountain men and settlers. The policy of discouraging settlement was undercut to some degree by the actions of John McLoughlin, Chief Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver, who regularly provided relief and welcome to U.S. immigrants who had arrived at the post over the Oregon Trail. By the middle 1840s, the tide of U.S. immigration, as well as a U.S. political movement to claim the entire territory, led to a renegotiation of the agreement. The Oregon Treaty in 1846 permanently established the 49th parallel as the boundary between the United States and British North America to the Pacific Ocean. Early U.S. Land Disputes – Station Two – Missouri Compromise Directions: Please use the provided sheet on the Missouri Compromise to answer the following questions. Please do not write on this sheet. Instead, please record your answers on the answer sheet that was provided to you. Question 1: The Missouri Compromise had three significant provisions written in it when it was completed. What three things did the compromise call for? (Questions 1a, 1b, & 1c on your answer sheet). Question 2: In your opinion, was the Missouri Compromise a good solution for solving the problem of adding new states to the union? Why or why not? Question 3: What problems do your foresee with this compromise? Do you see any potential problems that could arise by dividing the country in half between free and slave? Question 4: How might this compromise lead to the Civil War? Question 5: Watch the following video on YouTube. After watching the video, answer the question. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UW_PBAm6Z80 What is something you learned from the video that you did not know before? Question 6: In what year was the Missouri Compromise passed? Station Two ~ Missouri Compromise The Missouri Compromise was passed in 1820 between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress, involving primarily the regulation of slavery in the western territories. It prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north except within the boundaries of the proposed state of Missouri. To balance the number of "slave states" and "free states," the northern region of what was then Massachusetts ultimately gained admittance into the United States as a free state to become Maine. This only occurred as a result of a compromise involving slavery in Missouri, and in the federal territories of the American west. A bill to enable the people of the Missouri Territory to draft a constitution and form a government preliminary to admission into the Union came before the House of Representatives in Committee of the Whole, on February 13, 1819. James Tallmadge of New York offered an amendment, named the Tallmadge Amendment that forbade further introduction of slaves into Missouri, and mandated that all children of slave parents born in the state after its admission should be free at the age of 25. The committee adopted the measure and incorporated it into the bill as finally passed on February 17, 1819, by the house. The United States Senate refused to concur with the amendment, and the whole measure was lost. During the following session (1819–1820), the House passed a similar bill with an amendment, introduced on January 26, 1820, by John W. Taylor of New York, allowing Missouri into the union as a slave state. The question had been complicated by the admission in December of Alabama, a slave state, making the number of slave and free states equal. In addition, there was a bill in passage through the House (January 3, 1820) to admit Maine as a free state. The Senate decided to connect the two measures. It passed a bill for the admission of Maine with an amendment enabling the people of Missouri to form a state constitution. Before the bill was returned to the House, a second amendment was adopted on the motion of Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois, excluding slavery from the Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north (the southern boundary of Missouri), except within the limits of the proposed state of Missouri. The vote in the Senate was 24 for the compromise, to 20 against. The amendment and the bill passed in the Senate on February 17 and February 18, 1820. The House then approved the Senate compromise amendment, on a vote of 90 to 87, with those 87 votes coming from Free State representatives opposed to slavery in the new state of Missouri. The House then approved the whole bill, 134 to 42 (the latter votes being from southern states). This meant that Maine would be admitted to the Union as a free state in the north, Missouri to the Union as a slave state in the south and an imaginary line would be drawn west from Missouri’s southern border at 36°30′ north. All land north of that line was deemed free territory and all land to the south of it was designated for future slave states. Impact on sectionalism During the decades following 1820 Americans hailed the 1820 agreement as an essential compromise almost on the sacred level of the Constitution itself. The Civil War broke out in 1861; historians often say the Compromise helped postpone the war. These disputes involved the competition between the southern and northern states for power in Congress and for control over future territories. There were also the same factions emerging as the Democratic-Republican party began to lose its coherence. In an April 22 letter to John Holmes, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the division of the country created by the Compromise Line would eventually lead to the destruction of the Union: ...but this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. it is hushed indeed for the moment. but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper. Congress' consideration of Missouri's admission also raised the issue of sectional balance, for the country was equally divided between slave and free states with eleven each. To admit Missouri as a slave state would tip the balance in the Senate (made up of two senators per state) in favor of the slave states. For this reason, northern states wanted Maine admitted as a free state. On the constitutional side, the Compromise of 1820 was important as the example of Congressional exclusion of slavery from U.S. territory acquired since the Northwest Ordinance. Following Maine's 1820 and Missouri's 1821 admissions to the Union, no other states were admitted until 1836, when Arkansas was admitted. The Missouri Compromise served as a Compromise between north and south until it was formally declared unconstitutional in 1857 during the Dred Scott case. However, by that time its relevance had already been undermined as it had been replaced by the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Compromise of 1850. Station Two ~ Missouri Compromise Text Page 1 Station Two ~ Missouri Compromise Text Page 2 Early U.S. Land Disputes – Station Three – Adams-Onis Treaty/1st Seminole War Directions: Please use the provided sheet on the Adams-Onis Treaty/1st Seminole War to answer the following questions. Please do not write on this sheet. Instead, please record your answers on the answer sheet that was provided to you. Step 1: Read page 299 (right hand column) in your textbook as a group to gain information about the Adams – Onís Treaty. Answer the questions below on your answer sheet. 1. Who was the American general whose presence in France convinced Spain they may not have control there? 2. Why do you think most Americans supported the American general’s actions in Florida? 3. How much did the Florida territory cost for Americans to purchase? 4. What were the terms of agreement for this treaty? 5. Whose names were the treaty named after? Step 2: Watch the School Tube video on the netbook. Click the link on the word document provided. Make sure to answer the questions as you watch the video. 1. What were Spain’s feelings towards France for selling the Louisiana Territory to the US? 2. What type of Americans came to Louisiana? 3. What type of “ground” was declared between Spain’s and America’s so-called boundaries? 4. Who resided in this area since there was no police control? Step 3: Read through the excerpt that explains in further detail what this treaty is all about. Answer the questions below on your answer sheet. 1. What year was the treaty ratified? 2. What country replaced Spain in the treaty? Step 4: Read page 299 (left hand column) in your textbook as a group to gain information about the 1st Seminole War. After you are finished reading the paragraph, please read through the information handout provided for you regarding the 1st Seminole War to answer the questions below. 1. Along with the Native Americans living in Florida, who else from America would migrate there? 2. Who came to Florida to stop the Seminole raids? Were they successful in stopping the Native Americans? 3. Where did some of the Seminole tribes end up residing since they refused the reservations? Step 5: For this step, please use the three pictures provided to you to answer the questions below. 1. In picture 1, explain the battle strategies used by both the Americans and Seminoles. 2. In picture 2, describe the importance for the Seminoles to seize the fort. 3. In picture 3, what do you believe would be the dialogue between the standing lieutenant and the general on horseback? Step 6: Follow the instructions on your answer sheet for filling in the map for the Adams-Onis Treaty and the 1st Seminole War. Watch this video for Station Three ~ Step #2: http://www.schooltube.com/video/1a66a9e3717c4033aa5d/The%20Louisian a%20Purchase%20and%20the%20Adams-Onis%20Treaty. Station Three ~ Step #3 - The Adams-Onis Treaty Also called the Transcontinental Treaty of 1819, the Adams-Onis Treaty was one of the critical events that defined the US-Mexico border. The border between the then-Spanish lands and American territory was a source of heated international debate. In Europe, Spain was in the midst of serious internal problems and its colonies out west were on the brink of revolution. Facing the grim fact that he must negotiate with the United States or possibly lose Florida without ANY compensation, Spanish foreign minister Onis signed a treaty with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. Similar to the Louisiana Purchase statutes, the United States agreed to pay its citizens’ claims against Spain up to $5 million. The treaty drew a definite border between Spanish land and the Louisiana Territory. In the provisions, the United States ceded to Spain its claims to Texas west of the Sabine River. Spain retained possession not only of Texas, but also California and the vast region of New Mexico. At the time, these two territories included all present-day California and New Mexico with modern Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and sections of Wyoming and Colorado. The treaty – which was not ratified by the United States and the new republic of Mexico until 1831 – also mandated that Spain relinquish its claims to the country of Oregon north of the 42 degrees parallel (the northern border of California). Later, in 1824, Russia would also abandon its claim to Oregon south of 54’40’ (southern border of Alaska). Station Three ~ Step #4 ~ Seminole Wars Most of the land we know today as Florida was at one time under Spanish rule but Americans living in the Southeast wanted the United States to take over Florida. Slaves in Georgia would run away to Florida settlements or hide with the Seminoles, a tribe of Native Americans in Florida. The Seminoles and runaway slaves often attacked the Georgia landowners and then fled back into Florida. To end these Seminole raids, General Andrew Jackson and his army came to northern Florida in 1817. Andrew Jackson not only put an end to the Seminole raids but also went on to capture two Spanish forts including the one at Pensacola, which was the capital of Spanish Florida. They realized that they could not keep the United States from taking over the Florida territory so in 1819 Spain agreed to sell Florida to the United States. The Adams-Onis Treaty was approved by Spain and the United States in 1821. Andrew Jackson served as the military governor of the newly acquired territory of Florida. After Florida became a territory of the United States, big changes followed. A new capital was built in Tallahassee and new farms were started. Within 10 years many white Americans moved to Florida. The Seminoles were ordered by the government to move out of Florida to reservations in the west, but many Seminoles refused. The Seminole Indian War was fought against the United States and most of the Seminoles were either killed or forced to leave their homeland and settle in the west. A few fled to the south and hid in the Everglades. Picture #1 Picture #2 Picture #3 Station Three ~ Step #5 Station Three ~ Step #6 Directions: Use the map below to help you answer the questions on your answer sheet regarding the 1st Seminole War. Early U.S. Land Disputes – Station Four – Monroe Doctrine Directions: Please use the provided resources to answer the following questions regarding the Monroe Doctrine. Please do not write on this sheet. Instead, please record your answers on the answer sheet that was provided to you. Step 1: Begin by reading pages 300-301 in your textbook to gain information about the Monroe Doctrine. Answer the questions below on your answer sheet. 1. Who is Simon Bolivar? 2. What are the four main points of the Monroe Doctrine? 3. Who was the president when this doctrine was passed? 4. What was the date of the Monroe Doctrine? 5. Why do you think the U.S. chose not to issue a joint statement with Great Britain to keep European influences out of Latin America? Step 2: After everyone finishes reading the text in your book, look at the text of the Monroe Doctrine that is provided. As a group, go through the lines and phrases that call for independence as well as those lines that say “keep out.” Highlight all of these lines and phrases. Step 3: Look at the map involving Central America and their previous rulers. As a group, discuss the term “vulnerable” and why each country would be so to these earlier rulers. Step 4: Choose one of the two cartoons below and record your answers to the corresponding questions on your answer sheet. Cartoon #1 Cartoon #2 Cartoon 1 Questions: 1. Describe what is happening in this cartoon. 2. Who does the figure in the foreground (front) represent? 3. Who do the figures in the background represent? 4. What is the message of the cartoon? Cartoon 2 Questions: 1. Describe what is happening in this cartoon. 2. Who is the figure on the right? 3. Who are the two figures on the left? 4. What is the figure on the right pointing to? 5. What is the message of this cartoon? Step 5: Follow the instructions on your answer sheet for filling in the map for the Monroe Doctrine. Station Four~ Step #2 The Monroe Doctrine “[where] the rights and interests of the United States are involved, … the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintains, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers… “The citizens of the United States cherish sentiments the most friendly in favor of liberty and happiness of their fellowmen on that side of the Atlantic. In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, … It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense… “We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the [friendly] relations existing between the United States and [European] powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety…”