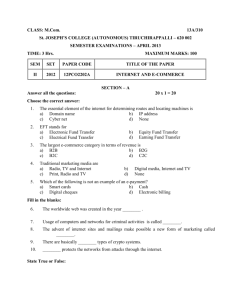

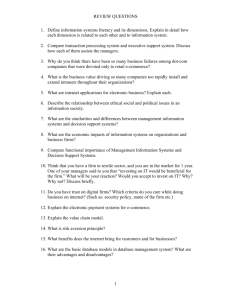

E-commerce

advertisement