WRITING OUTDOORS A Natural Reader - WWF

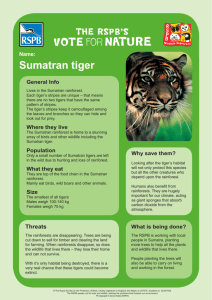

advertisement