Response Letter to FDIC Core and Brokered Deposits Study

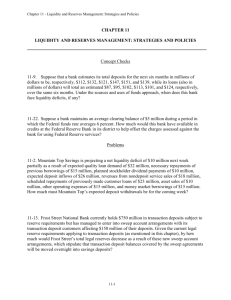

advertisement