Here - The Continuing Legal Education Society of BC

advertisement

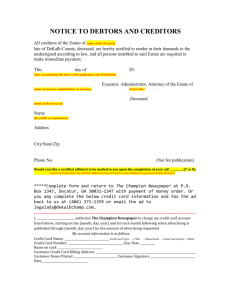

ESTATES: OUT OF THE ORDINARY PROBLEMS PAPER 2.2 Ongoing Liabilities These materials were prepared by Shelley A. Bentley of Kerr Redekop Leinburd & Boswell, Vancouver, BC, for the Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia, June 2008. © Shelley A. Bentley 2.2.1 ONGOING LIABILITIES I. Liabilities Incurred by the Deceased..................................................................................... 2 A. Duty of Executor/Administrator Duty of Executor in Meeting Claims.............................. 2 B. Specific Types of Liabilities .................................................................................................. 2 1. Support Obligations...................................................................................................... 2 a. Does the Court Order/Agreement Provide for Support to Continue Beyond the Payor’s Death? ................................................................................... 3 b. Can an Agreement be Challenged After Death? ................................................... 3 2. Mortgages ...................................................................................................................... 3 a. Land of Deceased Subject to Mortgage.................................................................. 3 b. Deceased’s Mortgage Assumed by Purchaser ........................................................ 4 3. Guarantees..................................................................................................................... 5 4. Leases............................................................................................................................. 6 C. Advertising for Creditors...................................................................................................... 6 D. Disputed Claims.................................................................................................................... 6 E. Unenforceable Claims Against the Estate............................................................................. 6 1. Limitation Periods ........................................................................................................ 6 2. Confirmation of the Debt ............................................................................................. 7 F. Presumption when Legacy Given to Creditor...................................................................... 7 G. Compromising Claims.......................................................................................................... 7 H. Communication with Creditors ........................................................................................... 7 II. Death of a Litigant ............................................................................................................... 8 A. Power of Executor and Administrator to Bring or Defend Actions..................................... 8 B. What Kinds of Actions are Sustainable After the Death of a Litigant?................................. 8 1. Actions for Wrongs Done to or by Deceased ............................................................... 8 a. Loss by the Deceased............................................................................................. 8 b. Actions Against the Deceased ............................................................................... 9 2. Family Relations Act/Divorce Act............................................................................... 9 C. How is the Action Commenced/Continued After the Death of a Litigant?...................... 10 D. If No Personal Representative for a Deceased Litigant/Interested Party in Active Litigation............................................................................................................................. 11 III. Foreign Assets .................................................................................................................... 12 A. Classification of Movables and Immovables ....................................................................... 13 B. Where are Movables Located?............................................................................................. 13 C. Law Governing Movables and Immovables........................................................................ 13 D. Law Governing Immovables............................................................................................... 13 E. Domicile.............................................................................................................................. 14 F. Transferring Assets Located Outside BC ............................................................................ 14 1. Immovables ................................................................................................................. 14 2. Movables ..................................................................................................................... 14 3. Recognition of a BC Personal Representative by a Foreign Jurisdiction.................... 14 4. Resealing vs. Ancillary Grants .................................................................................... 14 5. Conflicting Laws in Foreign Jurisdictions .................................................................. 15 2.2.2 IV. Bonus Point Plans .............................................................................................................. 15 I. A. Liabilities Incurred by the Deceased Duty of Executor/Administrator Duty of Executor in Meeting Claims Personal representatives have a duty to determine liabilities of the deceased, retain sufficient assets to satisfy these liabilities, pay the liabilities and perform all enforceable contracts made by the deceased. The case of McKay v. Howlett et al., 2003 BCCA 555 reminds us of the nature of a personal representative’s duty in the context of payment of debts. In this case the deceased had failed to fully report income that she received from the UK for many years. Upon becoming aware of this, one of the executors, Mr. McKay, submitted revised returns to CRA. CRA reassessed the deceased’s returns back to 1989 but declined to reassess returns prior to 1989. Mr. McKay formed the opinion the assessed amounts for 1989 to 1995 were insufficient and was unhappy with CRA’s decision not to assess tax for the years 1983 to 1988. He asked CRA to reassess and CRA replied by letter confirming that a decision had been made not to reassess. Mr. McKay refused to distribute the remainder of the estate and informed the beneficiaries that he intended to apply to court for directions. The beneficiaries applied to have Mr. McKay removed as executor. The BCCA commented (para. 15) … Mr. McKay has devoted much time since 1998 attempting to document taxes owing by the deceased and trying to compel the Canadian Customs and Revenue Agency to collect or accept it … He says that under s. 159 of the Income Tax Act he is responsible for the payment of taxes and that to distribute the remaining assets to the beneficiaries would be to commit or be a party to a criminal act. 16 The beneficiaries and the co-executor take the position that Mr. McKay’s insistence on pursuing taxes that the Government of Canada does not want to collect has held up the distribution of the assets of the estate for an inordinate amount of time and that by taking the action that he does Mr. McKay is demonstrably not acting in the best interest of the beneficiaries. The trial judge accepted this position and ordered the removal of Mr. McKay as executor. The BCCA dismissed the appeal of the trial judge’s decision. B. Specific Types of Liabilities 1. Support Obligations See “Ties that Bind? Support and the Payor’s Estate” written by David C. Dundee for CLE Aging Death and Divorce, February 2007. Unless a support order or agreement provides otherwise support dies with the payor (Despot v. Despot Estate (1992), 42 R.F.L. (3d) 218). Support arrears are binding on the estate of the payor (British Columbia (Public Trustee) v. Price (1990), 25 R.F.L. (3d) 113). The case law is conflicting on the point of whether under the Divorce Act Parliament even has the jurisdiction to bind a payor’s estate. See Linton v. Linton (1990), 30 R.F. L. (3d) 1, where the Ontario Court of Appeal concluded that there is ample authority to support such jurisdiction. See also Carmichael v. Carmichael (1993), 43 R.F. L. (3d) 145 where the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal found that legislation empowering a court to make an order imposing an obligation on a person’s estate to 2.2.3 provide periodic maintenance payments would be legislation relating to succession of property (a provincial power) rather than marriage and divorce and would be ultra vires Parliament. A number of BC decisions have held support orders last beyond the death of the payor without specifically examining the issue of their jurisdiction. So the current weight of authority in BC appears to support the jurisdiction of a divorce order to bind the payor’s estate. See Leckie v. Leckie, [1995] B.C.D. Civ 1645-38 (S.C.), Tyerman v. Tyerman, [1999] B.C.J. No 2327 (S.C.). a. Does the Court Order/Agreement Provide for Support to Continue Beyond the Payor’s Death? Whether a court order or an agreement provides for support to continue beyond the death of the payor is a matter of construction. In his paper referred to above, Mr. Dundee offers a useful guideline for construction. He concludes that whenever in an order or an agreement support is limited or defined without reference to the possibility of death the obligation has been held to continue beyond the payor’s death. For example, where support was to continue for a specified period of time (three years—Brubacher v. Brubacher Estate (1997), 30 R.F. L. (4th) 276 (Ont. G.D.), or “during her life”—Kirk v. Eustache (1937), A.C. 491) support was held to continue beyond death. Similarly where support is to continue until the happening of an event a support obligation has been held to survive death (“until further order of the court”—In Re Hurley Estate (1973), 8 N.B.R. (2d) 569 (although see Sugden v. Sugden, [1957] 1 All E. R. 300 (English Court of Appeal) where the such words “until further order until … the children … attain the age of 21 years” were held not to bind the estate to pay child maintenance), “until the child turned 21, left home (or school), married or died”—Wilson v. Wilson Estate, [1998] B.C.J. No. 2516 (S.C.). b. Can an Agreement be Challenged After Death? When an agreement is interpreted to provide for support beyond the death of the payor the personal representative of the payor must be aware that such contractual terms do not bind the court. Such arrangements may still be subject to review if a claim is made by the surviving spouse under the Wills Variation Act or the Estate Administration Act (Boulanger v. Singh (1983), 16 E.T.R. 19 (B.C.S.C.), Wagner v. Wagner Estate (1991), 37R.F.L. (3d) 1 (B.C.C. A.)). See Steernberg v. Steernberg Estate, 2006 BCSC 1672, where (at para. 72) Martinson J. commented that the analysis in Hartshorne v. Hartshorne, (2004 SCC 22) upholding the sanctity of a bargain in the context of a marriage agreement was of limited assistance in the wills variation context. 2. Mortgages a. Land of Deceased Subject to Mortgage Subject to words to the contrary, a beneficiary of a gift of land takes the land subject to any mortgage on it. Furthermore, s. 30 of the Wills Act gives to the mortgagee the right to obtain payment of the mortgage debt out of the mortgaged land, the other assets of the estate or otherwise. Primary liability of mortgaged land 30(1) In this section, “mortgage” includes an equitable mortgage, and any charge, whether equitable, statutory or of other nature, including a lien or claim on freehold or leasehold property for unpaid purchase money, and “mortgage debt” has a meaning similarly extended. (2) If a person dies possessed of, or entitled to, or under a general power of appointment by the person’s will disposes of, an interest in freehold or leasehold property that, at the time of the person’s death, is subject to a mortgage, and the deceased has not, by will, deed or other document, signified a contrary or other intention, the interest is, as between the different persons claiming through the deceased, primarily liable for the payment or satisfaction of the mortgage debt. 2.2.4 (3) For the purposes of subsection (2), every part of the interest, according to its value, bears a proportionate part of the mortgage debt on the whole interest. (4) A testator does not signify a contrary or other intention within subsection (2) by (a) a general direction for the payment of debts or of all the debts of the testator out of the testator’s personal estate or the testator’s residuary real or personal estate, or the testator’s residuary real estate, or (b) a charge of debts on that estate, unless the testator further signifies that intention by words expressly or by necessary implication referring to all or some part of the mortgage debt. (5) Nothing in this section affects a right of a person entitled to the mortgage debt to obtain payment or satisfaction either out of the other assets of the deceased or otherwise. (emphasis added) In Parritt-Ericson v. Ericson Estate, 2006 BCSC 1409, Mr. Ericson and his wife purchased two properties in joint tenancy partly with funds from two lines of credit registered against the properties. Upon the Mr. Ericson’s death the wife applied for an order that her husband’s estate owed one half of the principal amount of the two lines of credit. Given that the joint debt was used to acquire the land and the wife, as the surviving joint tenant, received all of the land the court found that the wife would be unjustly enriched if the estate paid half of the debt. At para. 28: Although I was inclined to think that the respondents’ argument on s. 30(2) of the Wills Act has merit, I do not have to rely on it as I think equity is against the petitioner’s claim. To saddle the estate with one-half of the debt in the particular circumstances is unjust and the petition must be dismissed. An Ontario case, Re Hicknell (1981), 10 E.T.R. 288 (Ont. H.C.) held that a beneficiary entitled to land took it subject to the mortgage but was not entitled to the benefit of the life insurance because the insurance was payable to the estate. The deceased purchased a life insurance policy through Metropolitan Life and added a rider to provide coverage payable to the estate of $200 per month for 25 years. The purpose of this was to look after mortgage payments. He had considered purchasing mortgage life insurance but the cost of the premiums was prohibitive. When a beneficiary is to take ownership of the real property charged with a mortgage and the mortgage terms permit the beneficiary to assume the mortgage, the personal representative should, on behalf of the estate, ask the lender for a release of the covenant to pay. An interesting question arises in the context of a mortgage taken out as collateral to a debt for a purpose unrelated to the purchase of the property. The testate succession committee involved in the BCLI’s Succession Law Reform Project recommended (BCLI Report #45, page 46, June 2006) that a new provision based on the underlying principles of s. 30 extend to registered charges on real and tangible personal property to the extent of the indebtedness relating to the acquisition, preservation or improvement of the asset. The recommendation envisages property would pass subject to primary liability only to the extent of the portion of the debt incurred for these purposes. b. Deceased’s Mortgage Assumed by Purchaser A deceased could be liable on the covenant to pay for a mortgage assigned to a purchaser of the deceased’s property. It is important to find out whether a release of the covenant to pay was obtained in cases where the deceased’s mortgage was assumed by a third party. Under ss. 20 to 24 of the Property Law Act when property (the borrower’s residence) is sold and the purchaser assumes an existing mortgage, the original borrower will be released from liability three months after the term of the mortgage expires unless the lender demands payment from the original borrower on the due date. 2.2.5 3. Guarantees Under the Law and Equity Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 253, s. 59(6) in order to be enforceable a guarantee (other than those arising by operation of law) must be in writing or evidenced by an act of the guarantor that is consistent with the guarantee. Often the difficulty lies in discovering the guarantee. Most liabilities come to light by careful tracking of mail, bank statements and documents left in the deceased’s residence. But these methods rarely reveal the deceased’s obligations when it comes to guarantees. Guarantees are frequently given to assist family members or to finance business. The personal representative should question family members and examine all documents relating to the deceased’s business to determine the nature of all liabilities. A guarantee is a contract to be answerable for the debt, default or miscarriage of the principal and the liability of the surety is an obligation to make good the deficiency of the principal. The liability of a surety is contractual in nature. The extent of the liability is determined by a construction of the contract. There are three basic types of guarantees: specific guarantees, continuing guarantees and all accounts guarantees. Under fixed guarantees the surety is liable for a particular or fixed obligation (e.g., for a term loan). Under a continuing guarantee the surety is liable for a series of transactions or for obligations arising during the term of the guarantee (e.g., covering a series of transactions like the guarantee of a line of credit). In continuing guarantees the guarantor is not discharged from liability simply because the principal at one time pays off the balance. Each time a new advance is made the surety’s liability is revived. In an all accounts guarantee the surety is liable for any amount owed by the principal to the creditor irrespective of the basis on which the debts came into being. The death of a guarantor does not automatically extinguish liability of the surety. The terms of a guarantee govern its enforceability. While liability of a deceased for a fixed guarantee may be fairly clear an interesting issue arises in the case of continuing guarantees where advances continue after the death of the surety. Is the estate liable for advances made after the death of the surety? McGuinness, The Law of Guarantee (2nd ed., 1996), page 358 the author sums up: The death of the surety does not in and of itself terminate the liability of the surety in respect of advances made under a continuing guarantee after the date of death. However, it would seem that a continuing guarantee automatically terminates or becomes cancelled once notice of the death of the surety has come to the attention of the creditor. Since a continuing guarantee is in the nature of an on-going offer to contract, I would not be possible for the offeree (the creditor) to accept such an offer once he becomes aware that the offeror (the surety) is deceased. While this is the case at common law the terms of the contract may alter this. Most continuing guarantees contain provisions making them determinable upon notice. An example of such a provision is: This guarantee shall be continuing security and shall remain in force notwithstanding any disability or the death of the guarantor until determined by three months’ notice in writing from the guarantor or the personal representatives of the guarantor. (National Westminster Bank plc v. Hardman (1988) Fin. L.R. 302 (C.A.) The terms of the contract should be examined in order to assess the right to terminate liability upon notice. Once established, the notice provisions should be strictly observed. In the absence of express provision, it seems that even though no actual notice has been given by the executor the fact that the surety’s death has come to the attention of the creditor will operate as a revocation of the guarantee. (See Harriss v. Fawcett, [1873] L.R. 8, Ch. App. 866, where six months’ notice was required but never given. The creditor had knowledge of the guarantor’s death and due to the surrounding facts the court decided that equity disentitled the creditor from relying on the fact that no formal notice was given. See also Re Whelan, [1897] 1 Ir. R. 575, Coulthart v. Clementson (1870), 5 Q.B.D. 42). In all three of these cases the creditor had actual knowledge of the deceased’s death.) If continuing liability is 2.2.6 established sufficient assets should be retained to meet the liabilities. Failure to do so could be considered mismanagement on the executor/administrator’s part and could result in personal liability. 4. Leases Leases are contracts and whether a lease terminates upon death of the lessee or of the lessor or both is a matter of construction of the contract. As with any other continuing liability the personal representative should examine the terms of the lease, give any required notice in the manner prescribed, and maintain sufficient assets in the estate to meet all future liability under the lease. Many leases require insurance to be maintained. Often insurance contracts consider failure to occupy leased premises for more than a specified period of time (e.g., three months), to be a breach. If the death of the lessee frustrates the purpose of the lease the personal representative should consider negotiating termination of the lease and a compromise of the amount owing. A release should be obtained. C. Advertising for Creditors What does advertising for creditors do? Advertising for creditors in accordance with the statutory requirements set out in s. 38 of the Trustee Act offers protection to an executor/administrator from personal liability for debts of the deceased of which he or she was unaware at the time the estate was distributed. Beneficiaries remain liable for debts up to the full value of their inheritances. D. Disputed Claims When a claim is disputed by the personal representative s. 66 of the Estate Administration Act provides a mechanism for limiting the time in which a creditor can bring an action to enforce the claim. The personal representative delivers a notice of intention to dispute to the claimant, the claimant has six months to commence an action after which the claim is barred forever. The six months starts to run after giving notice if any part of the debt is due at the time the notice is given. Otherwise the six months starts to run after part or all of the debt is due. Query whether this section can be used to limit or resolve the liability of a deceased guarantor. E. Unenforceable Claims Against the Estate Unenforceable claims should not be paid by the personal representative. This seems trite to say but it can cause difficulty in the context of family loans. It is common for a parent to loan funds to an adult child and to suspend the collection of principal and interest for significant periods of time. 1. Limitation Periods In BC under the Limitation Act, s. 9, claims are extinguished by the expiration of the limitation period set by the Act. As a result executors who pay claims barred by a limitation period to the detriment of beneficiaries may find themselves personally liable. Limitation periods for recovery of debt vary depending on the type of debt action. The period is 10 years for recovery of money on account of wrongful distribution of trust property and for the recovery of a judgment for payment of money. There is no limitation period for a debtor in possession of collateral to bring action to redeem the collateral. However, most other debt actions have a six year limitation period (ss. 3(5) and 3(6) of the Limitation Act). The limitation period generally starts to run on the date on which the right to bring the action arose. This in turn depends on the terms of the loan. The limitation period begins from the earliest time at which repayment can be required. So for loans with an acceleration clause requiring repayment in full on the first date a payment is missed the limitation period begins on the first date a payment is missed. 2.2.7 For loans made payable on a contingency basis, for example, where repayment is dependent upon the happening of a specified event or circumstance, the cause of action arises when the contingency occurs. With respect to promissory notes made payable upon demand the time starts to run on the date the note is made. No actual demand is necessary. This is to be distinguished from a demand promissory note made payable upon the presentment of the note itself. In this case the limitation period begins upon presentment of the note. 2. Confirmation of the Debt The limitation period can be extended or postponed by certain actions the most relevant of which in the context of a trustee’s involvement in an action for recovery of debt is the “confirmation” of the debt pursuant to s. 5(1) of the Limitation Act. The confirmation must take place before the expiry of the limitation period. Confirmation can be an acknowledgement of the debt or a part payment of the debt. Section 5(5) requires the acknowledgement to be in writing and signed by the maker of the acknowledgement. Section 5(2)(b) provides that an acknowledgement has effect regardless of whether the promise to pay may be discerned from the acknowledgement or whether it was accompanied by a refusal to pay. A refusal to pay can in some circumstances constitute an acknowledgement. The personal representative should as soon as possible determine the appropriate limitation period applying to a debt to the deceased and be aware of the opportunity to confirm the debt if necessary. (See “Loans to Children and Others” prepared by E. Jane Milton for CLE “Wills, Estates and TrustsSelected Topics,” November 2001.) F. Presumption when Legacy Given to Creditor There is a fairly narrow rule at common law that a legacy (not a portion of residue or a contingent gift or a gift in specie) given to a debtor that is greater than or equal to a debt owed to the debtor by the testator is presumed to be in satisfaction of the debt, subject to a contrary intention being shown. The debt must exist when the will is made. (See Advancement and Satisfaction in Wills, Estates and Trusts conference, CLEBC, 1998.) G. Compromising Claims Under s. 65 of the Estate Administration Act an executor has the power to compromise claims without responsibility for loss. It is interesting to note that the section does not refer to an administrator. However, under common law this power also applies to administrators (Pennington v. Healey (1833), 149 E.R. 455 (Ex.)). H. Communication with Creditors It is common for ongoing financial obligations to be held up pending the realization of the deceased’s estate. The best policy in dealing with creditors is communication. It is best to keep creditors informed about the progress of matters, to provide reassurance that the debt will be paid and to give an estimate of the timing before payment will be received. 2.2.8 II. A. Death of a Litigant Power of Executor and Administrator to Bring or Defend Actions Section 58 of the Estate Administration Act confers the same powers on an executor and administrator to bring or defend an action “in the nature of the common law action or writ of account” as the deceased would have if living. Only the personal representative on behalf of the estate has standing to complain of wrongs done to the estate. See Engel v. Engel, 2005 BCSC 33. See also Cooke v. Cooke Estate, 2005 BCCA 263 where beneficiaries were allowed to bring an action to attack an inter vivos transaction that had the effect of partially depleting the estate. However, in this case the executor was the main beneficiary of the inter vivos gift. B. What Kinds of Actions are Sustainable After the Death of a Litigant? Whether or not an action can be continued by personal representative depends on the cause of action and sometimes the stage of the proceeding. At common law death was once regarded as terminating most legal rights other than contractual rights. That rule has been almost completely eroded. Sections 58, 59, 60 and 61 of the Estate Administration Act provide the basis for a personal representative’s rights to bring, continue or defend actions by or against a deceased person. 1. Actions for Wrongs Done to or by Deceased a. Loss by the Deceased Section 59(2) provides that an executor/administrator may continue or bring an action for loss or damage to the person or property of the deceased on behalf of the deceased with the same rights and remedies as the deceased would, if living, be entitled to. However, under s. 59(3) recovery by the executor/administrator for the following is expressly prohibited: • damages in respect of physical disfigurement or pain or suffering caused to the deceased; • if death (of the deceased) results from the injuries, damages for the death, or for the loss of expectation of life (unless the death occurred before February 12, 1942); • damages in respect of expectancy of earnings after the death of the deceased that might have been sustained if the deceased had not died. Furthermore ss. 59 and 60 of the Estate Administration Act do not apply to actions of libel or slander. Nothing in ss. 59, 60 or 61 derogates from any rights conferred by the Family Compensation Act. The Family Compensation Act is legislation designed to allow relatives of the deceased to collect damages for pecuniary loss proportioned to the injury resulting from the death to the respective dependants. The Act allows a deceased’s spouse, parent or child (including those to which the deceased stood in loco parentis) to claim. In addition to the remedies that would be available to a deceased if living, a personal representative bringing an action under s. 59(2) may also claim damages in respect of reasonable disposition and funeral expenses. The executor/administrator cannot pursue on behalf of an estate (taken from Annotated Estates Practice, 2007, CLEBC, updated yearly) 2.2.9 • claims for exemplary or punitive damages (Allan Estate v. Co-operators Life Insurance Co, 1999 BCCA 35); • judicial review of an administrative decision where the decision was personal to the deceased (Collins v. Abrams, 2002 BCSC 1774); • claims for pain and suffering and loss of income, where the plaintiff dies after trial but before judgment is rendered (Monahan Estate v. Nelson, 2000 BCCA 297); • declaratory relief regarding a deceased’s rights under the Constitution or Charter (Stinson Estate v. British Columbia, 1999 BCCA 35); • a human rights complaint under the Human Rights Code, R.S.B.C. 1996, c.210(British Columbia v. Goodwin, 2005 BCSC 154, aff’d 2005 BCCA 585, leave to appeal to SCC dismissed). The executor/administrator can pursue on behalf of an estate: b. • A claim for malicious falsehood (Goldmanis v. Kajaks (1976), 6 W.W.R. 506). (This cause of action is to be distinguished from an action for libel or slander which is expressly prohibited.) • A claim for loss of expectation of life so long as the death was not caused by the tortfeasor (Lankenau Estate v. Dutton (1991), 55 B.C.L.R. (2d) 218). • An action under the Wills Variation Act (Re Calladine Estate (1958), 25 W.W.R. 175 (B.C.S.C.)). • An action for constructive or resulting trust (Nowick Estate v. Lachuk Estate (1989), 33 E.T.R. 103). Actions Against the Deceased Section 59(6) deals with actions against the deceased or the estate. Section 59(6) of the Estate Administration Act states: If a person alleges that the person has suffered loss or damage by the fault of another and the person alleged to be at fault dies, the person wronged may (a) continue against the executor or administrator of the deceased any action on that account pending against the deceased at the time of the deceased’s death, or (b) within the time otherwise limited for the action, bring an action for the loss or damage, naming as defendant in it (i) the executor or administrator of the estate of the deceased, or (ii) the deceased. (emphasis added) (Note: this section does not apply to an action of libel or slander.) If a deceased is named as defendant, the action is valid despite the fact that the defendant is dead at the time the action is commenced (s. 59(7)). 2. Family Relations Act/Divorce Act Actions under the Divorce Act and the Family Relations Act cannot be commenced if one of the proposed parties has died. The death of a spouse after a Divorce Act action has been commenced ends the action. Even in a case where a divorce order was granted but not entered before the death of the petitioner, no divorce followed Alexa v. Alexa (1995), 14 R.F.L. (4th) 93 (B.C.S.C.). British Columbia (Public Trustee) v. Price, 2.2.10 1990 BCCA 705, concerned the enforcement of a divorce order for child maintenance after the death of the payor and a application to register an Alberta order in BC. Mr. Justice Lambert commented on specific provisions of the Divorce Act in part IV of the decision: It will be readily seen that a ‘support order’ under s-s.15(2) is ‘an order requiring one spouse to ... pay.’ A spouse is a man married to a woman, or a woman married to a man. For the purposes of s.15, spouse includes a former spouse. A person is a spouse only while married. After the marriage ends a former marriage partner becomes a former spouse. But once a person dies, all that is left is a corpse, an estate, and a personal representative. The corpse is not a person at all. The estate is only a legal concept. The personal representative could be a corporation. None of them is either a spouse or a former spouse. So in my opinion a ‘support order’ under s-s.15(2) cannot be made once the person required to pay is dead. Nor can it be made against an estate. The order of Mr. Justice Hutchinson is therefore not a ‘support order’ under s-s 15(2). Even if it did nothing except set out the arrears that had accrued during Raymond’s lifetime it would not meet the conditions for being a ‘support order’ under s. 15. Where in a Family Relations Act action a triggering event under s. 56 of the Act has occurred before the death of a spouse the action can be continued by the deceased spouse’s personal representative. In Fong v. Fong (1981), 25 R.F.L. (2d) 123 (B.C.C.A.) administratrix ad litem was permitted to carry on an action for a determination and division of family assets pursuant to a declaration of irreconcilability. An action under s. 51 of the Family Relations Act that there is no reasonable prospect of reconciliation (a triggering event) cannot be maintained by a personal representative and is not assisted by s. 59 of the Estate Administration Act because there is no damage to person or property (Zuk Estate v. Zuk, 2007 BCSC 300). The personal representative cannot continue a deceased payor’s application to retroactively vary support or reduce arrears (Crain v. Crain, [1996] B.C.J. No. 1155 (S.C.)). C. How is the Action Commenced/Continued After the Death of a Litigant? For actions commenced against the deceased pursuant to s. 59(6)(b)(ii), s. 60 of the Estate Administration Act provides the mechanism for continuing the action against the executor/administrator. Section 60 states (emphasis added): (1) This section applies to an action commenced under section 59(6)(b)(ii). (2) If probate or letters of administration of the estate of the person alleged to be at fault have been granted, the writ of summons may be validly served on the executor or administrator, in which case, (a) on proof of service being filed with the registrar of the court in the registry office in which the action was commenced, the registrar must amend the style of cause in the action to substitute the executor or administrator served as the defendant in the place of the named defendant, and (b) the action must continue against the executor or administrator. (3) On application of the plaintiff or the executor or administrator of the plaintiff and on the production of a certificate referred to in subsection (4), a court of competent jurisdiction may appoint a representative for the purposes of the action, to represent the estate of the deceased for all purposes of the action and to act as defendant. (4) The certificate required by subsection (3) is a certificate that (a) is issued by the district registrar of the Supreme Court at Victoria and dated not more than 30 days before the date on which the court hears the application under subsection (3), and 2.2.11 (b) certifies that no notice has been received that probate or letters of administration have been issued in British Columbia in respect of the estate of the deceased person alleged to be at fault within 90 days after the person’s death. (5) If a representative for the purposes of an action is appointed under subsection (3), the writ of summons in the action must be served on that representative. (6) On being served with the order of appointment under subsection (3) and the writ of summons, the person appointed must file a notice with the district registrar of the Supreme Court at Victoria that he or she has been appointed as representative for the purposes of the action. (7) If an executor or administrator is appointed in British Columbia in respect of the estate of the deceased person alleged to be at fault, the district registrar of the Supreme Court at Victoria must immediately notify the representative for the purposes of the action of the appointment of the executor or administrator. (8) If notice is given under subsection (7), (a) on receipt of the notice, the representative for the purposes of the action must file the notice with the registrar of the court in which the action was commenced, (b) the registrar of that court must amend the style of cause in the action to substitute the executor or administrator as the defendant in the place of the representative for the purposes of the action and must notify the plaintiff and the executor or administrator appointed, and (c) the appointment of the representative for the purposes of the action is then terminated and the executor or administrator appointed has sole conduct of the defence of the action. (9) All proceedings had or taken against a representative for the purposes of an action appointed under this section bind the estate of the deceased, despite any previous or subsequent appointment of an executor or administrator of the estate of the deceased person, and all proceedings had or taken in accordance with this section bind the estate of the deceased person. If a personal representative has been appointed there is no power under this section to appoint a different person to conduct the lawsuit. Re Wong Gem (1965), 54 W.W.R. 504 (B.C.C.A.) If there is no subsisting application the action is commenced by petition under Rule 10. Otherwise for subsisting actions, a notice of motion may be used. D. If No Personal Representative for a Deceased Litigant/Interested Party in Active Litigation If in the course of active litigation a litigant or other interested party dies and there is no personal representative appointed the court may proceed in the absence of a representative or appoint a “representative ad litem” to represent the estate for the purposes of the proceeding. The court issues a grant of administration ad litem. Such application is commenced during the proceeding by notice of motion. See s. 9 of the Estate Administration Act and Rule 5(19) and (20). Representation for deceased person in legal proceedings 9(1) If, in an action or other proceeding before the court, it appears to the court that a deceased person who was interested in the matters in question has no legal personal representative, the court may either (a) proceed in the absence of a representative, or 2.2.12 (b) appoint a person to represent the estate for the purposes of the action or proceeding, on the notice to the persons the court thinks fit, either specially or generally, by public advertisement or otherwise. (2) An order made by the court as referred to in subsection (1) and every order consequent on it, binds the estate of the deceased person in the same manner as if the deceased's legal personal representative had been a party to the action or proceeding and had appeared and submitted the deceased person’s interests to the protection of the court. Rule 5(19) and (20) reads: Representation of deceased person interested in a proceeding (19) Where the estate of a deceased person has an interest in a matter in question in a proceeding, but there is no personal representative, the court may proceed in the absence of a person representing the estate of the deceased person or may appoint a person to represent the estate for the purposes of the proceeding, and an order made or granted in the proceeding binds the estate to the same extent as it would have been bound had a personal representative of the deceased person been a party (20) Before making an order under subrule (19), the court may require notice of the application to be given to a person having an interest in the estate. The existence of a proceeding is a prerequisite to the appointment of a “representative ad litem.” The purpose of s. 9 is to be distinguished from s. 8 of the EAA. Section allows a representative ad litem to be appointed to represent the estate for the purposes of the proceeding. Section 8 allows an “administrator pending litigation” to be appointed to administer the estate if litigation to challenge or modify the will is pending or has been commenced. The administrator pendente lite has all the rights and powers of a general administrator other than the right to distribute the estate. The administrator pendent lite is supposed to be a neutral party. So, unless all beneficiaries and creditors consent to the appointment, the court generally will not appoint a party to the litigation. (Re Bazos (1964), 2 O.R. 236 (C.A.)). III. Foreign Assets The following discussion of foreign assets assumes that the domicile of the deceased is BC. Assets owned by the deceased and located outside of BC at the date of death present special problems. Even though the deceased’s will may have been properly probated in BC that fact may not be sufficient to transfer an asset located in a foreign jurisdiction. The laws of the foreign jurisdiction may impose restrictions on transfer which conflict with BC law and the provisions of the deceased’s will. Often the most frustrating and time consuming part of dealing with an estate is dealing with the deceased’s foreign assets. Clients should be warned about the time frame, the complexities and the commensurate expense involved. It is often necessary to hire counsel in a foreign jurisdiction. Because of the complexities involved and the necessity to coordinate matters in BC it is often BC counsel who is saddled with the responsibility of selecting appropriate foreign counsel. The situs or location of the asset and the determination of whether the asset is moveable or immovable determine which law governs the asset upon death. Formal validity is generally concerned with the form of the will and the manner of its execution. Essential validity is generally concerned with the validity of gifts in the will such as whether legacies are valid or whether the distribution in a will complies with forced heirship laws requiring a different distribution. 2.2.13 A. Classification of Movables and Immovables Laws in different countries vary on the issue of whether an asset is movable or immovable. The law of the place where an asset is located at the death of the deceased governs the issue of whether an asset is immovable or movable. In BC the conflicts of laws principles relating to movables and immovables are codified in the Wills Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 489, ss. 39 to 43. Section 39 defines movables generally as anything other than an estate or interest in land. All estates, interests and charges in and over land such as leases, rent charges, mineral rights, the interest of a mortgagee are considered immovables. Such definition in s. 39(1) of the Wills Act can also include personal property. B. Where are Movables Located? While some assets are easily classified as immovable (land) and movable (tangible personal property) the issue becomes more difficult when assets such as loans/debts, business interests and investments are concerned. Generally stocks are located where they can be effectively dealt with (where the register of transfers is required by law to be kept). Bank accounts are usually located at the bank branch where the account is kept. Trusts are located where they are administered. Depending on the type of debts (ordinary or specialty) the debt may be located where the debtor resides or it may be located where the debt document is found. Negotiable instruments that are transferable by delivery (essentially treated as paper money) are generally located where they are found upon the deceased’s death. C. Law Governing Movables and Immovables Which law governs the formal validity of the will, the essential validity of the will and the devolution of the asset? Generally where movables are concerned the law of the domicile of the deceased governs the formal and essential validity of the will and the devolution of the asset. Some jurisdictions may have legislated provisions in an attempt to validate wills. For example, in BC the Wills Act, s. 40, validates a will made outside BC in so far as the manner and formalities of making a will are concerned, and so far as it relates to movables, if that will is made in accordance with the law (a) where the will was made, (b) where the testator was domiciled when the will was made, or (c) of the testator’s domicile of origin. See also s. 43 of the Wills Act. It states: If the value of a thing that is movable consists mainly or entirely in its use in connection with a particular parcel of land by the owner or occupier of the land, succession to an interest in the thing, under a will or on an intestacy, is governed by the law of the place where the land is located. D. Law Governing Immovables Generally, the devolution of immovables and the formal and essential validity of the will involving the immovable, is governed by the law in the place where the immovable is located (see s. 39 of the Wills Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 489). There are exceptions so each specific situation should be researched. For example, the question of whether a subsequent marriage revokes a will is governed by the law of the province where the matrimonial domicile is located, rather than the law of the province where the property is located (Re Covone Estate (1989), 36 E.T. R. 114 (B.C.S.C. Master)). 2.2.14 E. Domicile Because the domicile of the deceased at death is so important to choice of law to be applied and a determination of the validity of the will and the distribution of assets the determination of domicile is an important first inquiry for an executor. Arguably for most people owning sizable assets in a foreign jurisdiction at death there is the possibility that the deceased’s domicile was not the place where the deceased resided at death. Beneficiaries who wish to “jurisdiction shop” may have information relevant to the deceased’s domicile that is contradictory. The concept of domicile, the rules relating to a change in domicile and the 3 basic kinds of domicile, domicile of origin (assigned at birth), domicile of dependency (assigned by legal presumption under specified circumstances) and domicile of choice, are discussed at some length in Chapter 10 of the British Columbia Estate Planning and Wealth Preservation manual published by CLE and updated annually. Domicile can be involuntary (domicile of origin, domicile of dependency) or acquired by choice (domicile of choice). For conflicts of law purposes a person’s domicile is, generally speaking, the place where the person lives and intends to continue living indefinitely. “‘Domicile’ in this context is the fixed, permanent and principal home to which a person, wherever temporarily located, always intends to return.” (B.C. Estate Planning and Wealth Preservation, section 10.3) While a person may be resident in more than one place at a given time, a person’s domicile is exclusive. F. Transferring Assets Located Outside BC 1. Immovables Because the devolution of immovable property is governed by the law of the place where the immovable is located, a personal representative must usually hire counsel in the foreign jurisdiction in order to determine whether the personal representative can deal with the property. If the will appointing the personal representative is recognized in the foreign jurisdiction commonly the personal representative will be required to reseal the BC grant in the foreign jurisdiction or to obtain an ancillary grant limited to the asset in question. In some jurisdictions an ancillary grant cannot be granted for letters of administration. In such jurisdictions a principal grant must be obtained. 2. Movables Because movable property is governed by the law of the deceased’s domicile at death in many cases the institution holding the asset in the foreign jurisdiction will release the asset upon production of a BC grant. However, depending on the practice in the particular jurisdiction or the rules of the institution holding the asset, resealing of the BC Grant or an ancillary grant may be required. In some cases proof that a tax clearance certificate has been obtained might assist. 3. Recognition of a BC Personal Representative by a Foreign Jurisdiction Many jurisdictions outside of BC will not recognize the authority of a personal representative who is not resident in that foreign jurisdiction. For example, Ontario will not allow a non-resident of Ontario to apply for letters of administration (Estates Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E.21, s. 5) and requires an executor who is a non-resident of Ontario to post a bond unless a judge orders otherwise under special circumstances (Estates Act, s. 6). 4. Resealing vs. Ancillary Grants It appears that the resealing of a grant involves the endorsement by a foreign court of the original grant obtained. The Probate Recognition Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 376 specifically provides for the resealing of foreign grants of probate and letters of administration in BC courts for certain 2.2.15 jurisdictions offering reciprocating resealing. These jurisdictions currently are all provinces and territories of Canada, the United Kingdom, the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia, New Zealand, British Guiana, South Africa, and Barbados. Those countries which are no longer part of the British Commonwealth (Hong Kong) do not fall under the definition of “British possession” in the Act and so, technically, the process of resealing should no longer be available. Because of the awkwardness of distance and unfamiliarity it is sometimes more convenient for the personal representative to deal with a foreign asset by means of an attorney. In such cases the personal representative can often apply for letters of administration to be granted to the attorney in the foreign jurisdiction. For those grants which cannot be resealed an ancillary grant is commonly applied for. An ancillary grant is a new grant, not an endorsement of the original grant. Sometimes, depending on the jurisdiction, a grant of administration with will annexed may be issued to the attorney for the personal representative. In situations involving resealing and ancillary grants in foreign jurisdictions security in the form of a bond is often a requirement, even in cases where a personal representative is appointed by will. 5. Conflicting Laws in Foreign Jurisdictions The most common areas where conflicting laws are at issue in the context of an estate is where community of property and forced heirship laws exist or where dependent’s relief legislation differs. Community of property laws are relevant not only to a deceased domiciled in BC at death when an immovable asset is located outside BC but also when a deceased who dies domiciled in BC was married in a community of property regime, regardless of whether or not the asset concerned is movable or immovable. California, Washington State and Quebec are community of property jurisdictions. A deceased’s estate may be subject to division with the surviving spouse. It may be necessary to obtain legal advice on the relevant jurisdiction to find out the rules on devolution. IV. Bonus Point Plans Points collected by the deceased under point or reward system plans (such as Airmiles, Aeroplan Miles, Affinity Points) generally do not have a cash value associated with them. However, these plans often allow the points to be assigned to another individual or a relative upon the death of the “collector.” Many of them have time limitations (a year is common) for the transfer or assignment. What is required in order to transfer the points when the holder of the points dies? The Airmiles plan requires proof of death and a letter signed by the deceased collector’s personal representative advising of the beneficiary. If there is no will or court appointed administrator, Airmiles authorities will accept a letter from the surviving spouse, and if none, then one of the children, and if none, then one of the parents of the deceased and if none, then one of the siblings of the deceased. Points are an asset of the deceased and so should be included in an asset and liability statement. Valuation is an interesting issue. Canada Revenue Agency considers “frequent flyer program credits” to be a taxable benefit in some circumstances (see Bulletin IT-470R). I am unaware of any interpretation bulletins that assist in assessing the fair market value of such a taxable benefit.