Feature article in Birding magazine

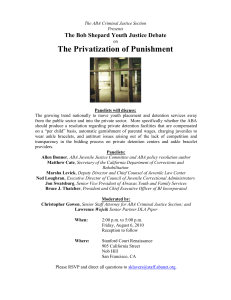

advertisement

Louisiana’s Crude How Citizen Scientists Help Monitor the Effects of Oil on Birds When we at the ABA first heard about the disaster that was unfolding in the Gulf of Mexico in April and May of 2010, our minds immediately turned to the birds that rely on the tidal marshes which make up the fertile feeding grounds of the fragile ecosystem along the Gulf coast. Three things were obvious: (1) We needed a system for coordinating and employing the volunteer service of ABA members in the region; (2) we needed to receive accurate, on-the-ground information; and (3) we needed to raise funds to help organizations get a handle on the impact of the situation. Thanks to the generosity and overall concern of our membership, we have been able to succeed on all fronts. Just as the ABA’s Gulf Coast Coordinator Drew Wheelan was arriving at ABA headquarters to outfit himself for a prolonged stay in Louisiana, Jared Wolfe and Erik I. Johnson, two Louisiana State University (LSU) graduate students, were contacting the ABA seeking volunteer observers and funding to help launch a mammoth oiled-bird survey along the whole north rim of the Gulf of Mexico. Wolfe and Johnson, in a collaborative effort with LSU’s School of Renewable Natural Resources and the Baton Rouge Audubon Society (BRAS), were in the process of developing what has become the standard for volunteer-based monitoring of oiled birds and habitats resulting from major oil spills like the Deepwater Horizon disaster. To help move the effort along, the ABA made a donation of $3,000 to the BRAS. This was followed with a call on our website for volunteers in the area to participate in the surveys. The National Wildlife Federation helped build volunteer capacity, and Ryan Mong, an intern from Evergreen State College in Washington, was put in place to lead the surveys throughout July 2010. Today the work continues. Both Wolfe and Johnson have presented the results of the summer surveys at a professional conference, they have been extensively involved with state and federal agencies, they have done public outreach, and they have been invited to speak at an upcoming symposium, “Deepwater These images by Bart Siegel bear witness to the hazards to marine life in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Siegel was a volunteer in a major grassroots effort, funded in part by the ABA, to document the effects of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. A major challenge for Siegel and his colleagues was to try to determine how many deaths were attributable to the oil gusher vs. other causes of mortality. The full impact of the disaster may not be known for years. Horizon Oil Spill–Lessons Learned,” at the 2011 Waterbird Society meeting. So many people rose to the occasion during this devastating event. Thanks go out to our membership for the goodwill and quick action in helping to get the monitoring efforts started, and to Jared Wolfe and Erik Johnson for taking on and successfully navigating such a daunting task. More information can be found on the Baton Rouge Audubon Society’s website <tinyurl.com/6yw6jgw>. To recount the horrific details of the oil spill as it unfolded, visit the ABA’s Gulf Coast page, with links to Drew Wheelan’s blog <aba.org/gulf>. The page and blog are no longer updated, but are preserved as a historical snapshot and reminder of the environmental disaster that took place. They are a tribute to the untold Top to bottom: Black Skimmer, Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle, apparent King Rail x Clapper Rail hybrid. Photos by © Bart Siegel. 48 number of birds that undoubtedly lost their lives in the summer of 2010. —David Hartley, ABA Director of Communications BIRDING • MARCH 2011 Awakening n the vast wetlands of the Gulf coast, dozens of sensitive waterbird species breed in highly productive marshes and estuaries, and on barrier Jared Wolfe Baton Rouge, Louisiana jwolfe5@tigers.lsu.edu Erik I. Johnson Baton Rouge, Louisiana ejohn33@tigers.lsu.edu islands. Great rookeries of herons, egrets, ibises, pelicans, and terns depend on the fragile ecosystem, which is often pounded by summer hurricanes and winter storms. The interior population of the endangered Piping Plover winters primarily along the sandy shores of the Gulf, and many other migratory shorebirds also use this landscape. For decades, humans have altered the hydrology of these coastal marshes such that this habitat is quickly disappearing. On 20 April 2010, British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded, adding one more insult to this already severely impacted ecosystem: uncontrolled crude oil spilling into the Gulf and drifting toward shore. According to the U.S. government, 6,104 birds are documented to have perished because of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Birds that survived the spill will most likely experience higher levels of cancer, decreased reproduction, and organ damage. Crude oil still threatens Louisiana’s coastal bird communities; researchers from the University of Georgia recently found substantial layers of oil-saturated sediment stretching from the Deepwater Horizon explosion site to the coastline, suggesting that much of the oil did not evaporate or dissipate but instead In the early 20th century, the Great Egret became a symbol for the ravages of the millinery trade. Today, the species faces threats that couldn’t have been imagined a hundred years ago. Photo by © Drew Wheelan. WWW.ABA.ORG 49 GU LF COA ST D IS A STER Royal Tern. Photo by © Drew Wheelan. One of the heroes in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon disaster was biologist, activist, and organizer Drew Wheelan. Supported in part by the ABA, Wheelan’s investigative reporting quickly attracted the attention of the national news media. His blog <aba.org/gulf> was candid, disturbing, and highly influential. Wheelan’s efforts resulted in donations by ABA members and friends in excess of $55,000, and these monies have been quickly dispersed to organizations doing on-the-ground monitoring and cleanup. These photos convey a sense of Wheelan’s nearly round-the-clock efforts in the Gulf. Royal Tern. Photo by © Drew Wheelan. 50 settled on the seafloor. Storm activity coupled with submerged layers of oil could severely re-contaminate stretches of Louisiana’s shoreline. Recognizing the potential impact of the Deepwater Horizon tragedy on our coastal bird communities, researchers associated with Baton Rouge Audubon Society and Louisiana State University implemented a “Citizen Scientist’s Protocol for Monitoring Oiled Birds in Louisiana” on 8 May 2010. This protocol is distinguished from most other avian survey methodologies by identifying individuals that show either visual or behavioral effects of oil contamination. During oil spills, surveyors (and the media) often focus on heavily oiled, immobile, or dead wildlife, and often address those BIRDING • MARCH 2011 Northern Gannet. Photo by © Drew Wheelan. Partially oiled American Oystercatcher. Photo by © Drew Wheelan. Shoreline cleanup. Photo by © Drew Wheelan. WWW.ABA.ORG 51 GU LF COA ST D IS A STER animals that are in the most immediate danger. The Louisiana Citizen Scientist protocol is designed to document individual birds with even small patches of oil on their plumage or exhibiting unusual behavior. Because small amounts of oil can be preened and ingested, the potential for illness or death is great. The Louisiana Citizen Scientist methodology was subsequently adopted by the National Audubon Society as their standard monitoring protocol throughout the Gulf coast region. Citizen scientists are playing an important watchdog role as this environmental crisis unfolds. Many months after the broken well-head was capped, they have continued to collect valuable scientific data and regularly document wildlife impacted by oil contamination. Bart Siegel, a citizen scientist hailing from New Orleans, submitted the following report after conducting a routine offshore survey: On 24 October 2010, our party of four boarded a boat bound for a barrier island 12 miles into the Gulf of Mexico. We anchored about 150 yards offshore and walked through the water carrying our gear over our heads. Upon the 52 island, which we [previously] visited on 2 October, we found a large increase in oil deposits. The deposits were back in the marsh grass as well as on the beach, within reach of high tide. Oil was also found just under the surface covered by a fresh layer of sand over a vast area of beach. A Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle was found on the beach, a recent mortality, along with a Black Skimmer and a Clapper Rail. The population of blue crabs that were abundant on our last inspection was all but gone. Reports are subsequently given to authorities to inform and guide mitigation efforts. Data are archived digitally and available to researchers for analysis. As concerned citizens, we are frustrated with our inability to stop the oil spill from damaging the Gulf coast’s fragile ecosystems. Although our collective ability to avert further damage is limited, our collective ability to document damage is critical. As the crisis unfolds, we hope to tell the birds’ story through analysis and by sharing data with interested parties for upcoming analysis and mitigation. To learn more, please visit us online <tinyurl.com/4l25ojl>. BIRDING • MARCH 2011