Indicators for Human Dimensions of Development

advertisement

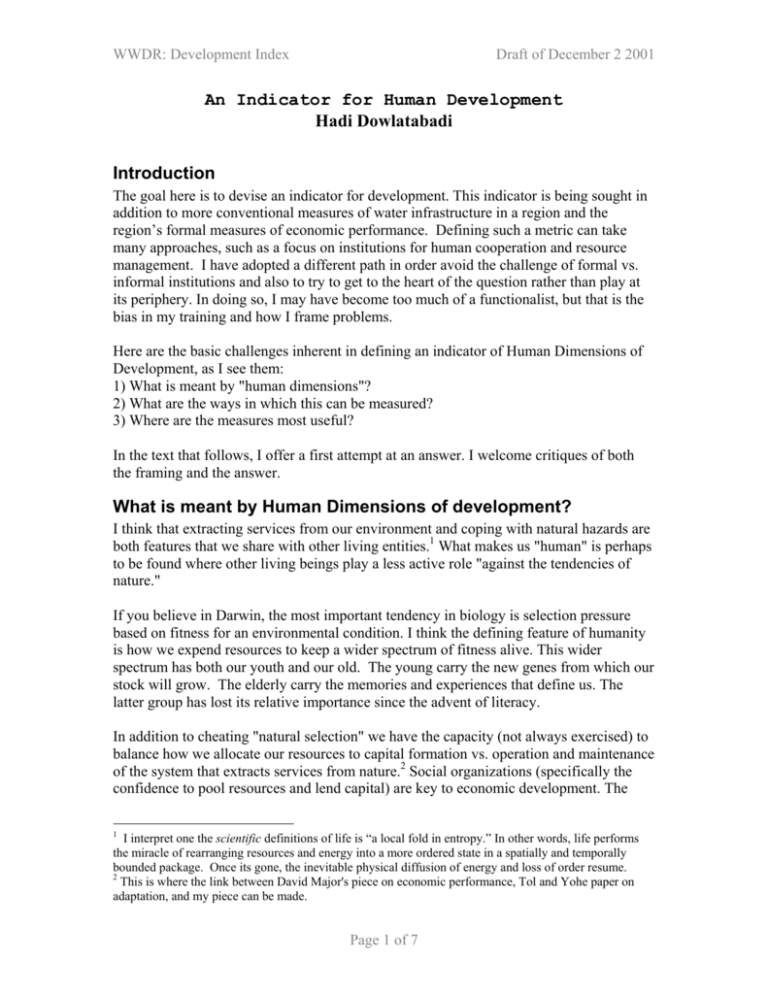

WWDR: Development Index Draft of December 2 2001 An Indicator for Human Development Hadi Dowlatabadi Introduction The goal here is to devise an indicator for development. This indicator is being sought in addition to more conventional measures of water infrastructure in a region and the region’s formal measures of economic performance. Defining such a metric can take many approaches, such as a focus on institutions for human cooperation and resource management. I have adopted a different path in order avoid the challenge of formal vs. informal institutions and also to try to get to the heart of the question rather than play at its periphery. In doing so, I may have become too much of a functionalist, but that is the bias in my training and how I frame problems. Here are the basic challenges inherent in defining an indicator of Human Dimensions of Development, as I see them: 1) What is meant by "human dimensions"? 2) What are the ways in which this can be measured? 3) Where are the measures most useful? In the text that follows, I offer a first attempt at an answer. I welcome critiques of both the framing and the answer. What is meant by Human Dimensions of development? I think that extracting services from our environment and coping with natural hazards are both features that we share with other living entities.1 What makes us "human" is perhaps to be found where other living beings play a less active role "against the tendencies of nature." If you believe in Darwin, the most important tendency in biology is selection pressure based on fitness for an environmental condition. I think the defining feature of humanity is how we expend resources to keep a wider spectrum of fitness alive. This wider spectrum has both our youth and our old. The young carry the new genes from which our stock will grow. The elderly carry the memories and experiences that define us. The latter group has lost its relative importance since the advent of literacy. In addition to cheating "natural selection" we have the capacity (not always exercised) to balance how we allocate our resources to capital formation vs. operation and maintenance of the system that extracts services from nature.2 Social organizations (specifically the confidence to pool resources and lend capital) are key to economic development. The 1 I interpret one the scientific definitions of life is “a local fold in entropy.” In other words, life performs the miracle of rearranging resources and energy into a more ordered state in a spatially and temporally bounded package. Once its gone, the inevitable physical diffusion of energy and loss of order resume. 2 This is where the link between David Major's piece on economic performance, Tol and Yohe paper on adaptation, and my piece can be made. Page 1 of 7 WWDR: Development Index Draft of December 2 2001 roots of credit unions can be found in Quakers history. Much of what we take for granted as part of the formal economy came about because social organizations grew so well established that the institutions could act in place of a personal network of social contacts. What can be measures of Human Dimensions of Development? Humans cheat natural selection through adaptation. Various modes of adaptation are often combined to make the environment inhabited by humans a hospitable one. Water, shelter, fire, food and waste disposal are all inanimate essentials to survival. Dealing with animals, coping with neighbors, surviving diseases and parasites are the animate side of the same coin. Knowledge gathering and transfer and genetic drift are the two mechanisms for enhanced adaptation and survival skills through time. Children are how new genetics enter the population3 and how we pass on knowledge. Their preparations and life experience are how we develop new skills and knowledge. The elderly are where much of the knowledge resides (in pre-literate societies). Thus, a healthy population and any form of education/apprenticeship are critical to cheating natural selection. Where the world is changing, this knowledgebase also needs to change. Some social organizations do not encourage this process. Clearly, a mismatch between knowledge and environmental conditions will lead to dysfunctional adaptive practices. Possible Metrics Given the importance of children, a natural indicator of development is child mortality. This metric is strongly modulated by vaccination, a relatively easy intervention that can be provided by outside entities. In fact, the worse the raw values for this indicator, the more likely that the attention of outside agencies are raised. The efforts of these groups will be accepted in all but the most isolationist regions and hence a “J-curve” of achievement will be evident where the bottom of the “J” will often be a true measure of local capabilities, while the truly desperate regions will have a higher level of achievement – achieved as a consequence of outside interventions. Another measure would be malnutrition among children. Malnutrition is an outcome of a number of factors: selective allocation of food among offspring, household level inadequacy of food, poor hygiene, and poor water quality. All of these are related to different facets of the human dimensions of development. Water quality and quantity are critical to good nutrition and health. In order for children not to suffer malnutrition, society must solve a number of social issues related to management of water resources. In a sense, where water stress is greatest, the achievement of the same level of nutrition is a testament to local success in developing this critical resource more effectively. Therefore, the proposed indicator would be based 3 With advances in genomic technologies, we are on the threshold of an era when this statement will no longer be true. Page 2 of 7 WWDR: Development Index Draft of December 2 2001 on malnutrition among children after accounting for income and water availability. The correction for these two factors is an attempt to tease out what the local social organization has achieved given the local context. Desirable Features of Indicators There are as many ideas about good indicator designs as there are indicators. I see no reason why I should abandon this great tradition. Therefore, staying true to a functionalist approach, I assert that an indicator is useful when it has been designed with three criteria in mind: have a range that reflects what is locally possible (e.g., water availability); focus attention on achievable objectives (i.e., have an upper bound that can be achieved given the resources that are locally available); have resolution about the system conditions where it matters (i.e., use the majority of a 5 point scale indicating different identifiable stages of achievable conditions). Constructing a fair indicator for human dimensions of development A fair indicator should recognize that economic power can be a substitute for social organization and development. As proof let me offer a simple comparison of life expectancy in centrally planned Asian countries versus other Asian nations – see table 1. Table 1, Comparing the impact of social institutions with wealth † National Group Centrally Intercept Coefficient for increase in (i.e., life expectancy life expectancy with wealth at no income) (natural log of GDP/cap.) Adjusted R2 25.1 5.9 0.53 34.9 4.2 0.80 planned Asia Other Asian nations Note: † Based on World Bank data on life expectancy and raw GDP per capita. The figures in Table 1 reveal that such simple models can have surprising explanatory power with Adjusted R2 of over 0.5. They also attest to the power of wealth when starting from a low income – i.e., the logarithmic relationship between income and life expectancy. The estimated model parameters also suggest that by the time a community reaches an income of $320 per capita, the centrally planned communities (here taken as being equivalent to having social development programs) will deliver a higher life expectancy than market based economies of similar per capita income. The life Page 3 of 7 WWDR: Development Index Draft of December 2 2001 expectancy achieved by a centrally planned economy with GDP per capita of $1000 is equal to a nation with GDP per capita twice that level (i.e., $2000/capita) if based on a market economy. The general idea presented above will be refined further and applied to childhood malnourishment. The reason I am choosing malnourishment rather than mortality is that mortality rates can be changed dramatically through vaccination programs. These require less persistent effort than feeding and nurturing children a healthy environment. Malnourishment can also be a consequence of frequent gastro-intestinal diseases, often associated with water-born pathogens. Therefore, malnourishment is an endpoint for both persistent effort to maintain children’s health and local water quality. Table 2, Correlation between measures of income (GDP/cap (ppp corrected) Water Availability (m3/cap) and Childhood malnourishment rate (%).† % of Children under GDP per capita (ppp Water age 5 malnourished corrected) availability % of Children under age 5 malnourished 1.000 GDP per capita (ppp corrected) -0.441 1.000 Water availability -0.135 0.038 1.000 Note: † Based on World Bank data on water availability, and purchasing power parity corrected GDP per capita, and % of children younger than 5 who are malnourished. This simple correlation reproduced in Table 2 presents evidence of the strong negative relationship between income and childhood malnourishment. A simple indicator of water availability does not have a strong correlation with malnourishment. Furthermore, there seems little relationship between GDP per capita and water availability. Thus, I used GDP/capita and water availability as independent variables that may be used to estimate malnourishment in different countries. Data availability limited the calculation of a 5 point indicator to 81 nations and territories. In many instances, there is little data on level of malnutrition. In a minority, the missing data are economic measures of GDP/cap and water availability. Nonetheless, the approach adopted here may be applied to as many complete datasets as can be assembled for an chosen scale of analysis. Page 4 of 7 WWDR: Development Index Draft of December 2 2001 The first step is to define a simple linear regression model relating malnourishment (as the dependent variable) to GDP/capita and Water availability per capita (as the independent variables). The residuals of this regression equation are insensitive to scale when log of GDP/capita are used as the independent variable. A summary of the regression results are presented in Table 3. Table 3, Regression Result Summary† Model Intercept Coefficient for Coefficient for Adjusted (i.e., % malnutrition with malnutrition with R2 Malnutrition at wealth water availability no income) (log of GDP/cap.) (m3/cap.) Income only 76.33 -17.04 Income & 76.02 -16.78 … -53.25 e-6 0.298 0.293 water The regression models explored above can only explain about 30% of the variability in observations. Something beyond water availability and economic power is responsible for the level of malnourishment. Thus, the residual of this model, i.e., what is not explained by economic and water availability is a measure of the human dimensions of development. Normalized residuals from the model can thus be used to construct a 5 point indicator. The normalized residuals span a ±2 sigma range from a mean of zero. A one sigma positive residual indicates that the above model under-estimates the extent of malnutrition. Thus, a region where such condition prevails has failed to attain the global norm of human dimensions of development. The reverse is true for a region where malnourishment is significantly above zero. By reversing the sign of the normalized residuals and shifting their mean to 2.5, a five point scale can be constructed where a score above 5 indicates a high level of development. Table 4 summarizes the indicator values for the observations used to generate this scale. A histogram of the scores is presented in Figure 1. Page 5 of 7 WWDR: Development Index Draft of December 2 2001 Table 4: Development Index (1-5 Scale, with 5 being high) Region/Nation Score Region/Nation Score Region/Nation Score Algeria 2.8 Georgia 4.2 Nicaragua 3.2 Angola 0.9 Ghana 2.4 Niger 0.6 Argentina 3.3 Guatemala 1.8 Nigeria 1.5 Armenia 4.1 Haiti 2.5 Oman 1.4 Australia 2.9 Honduras 2.1 Pakistan 1.3 Austria 2.9 India 0.7 Peru 3.0 Azerbaijan 3.8 Indonesia 1.1 Philippines 1.5 Russian Bangladesh 0.0 Iran, Islamic Rep 2.9 Federation 3.6 Belgium 2.9 Jamaica 3.7 Rwanda 2.7 Benin 2.2 Jordan 3.8 Saudi Arabia 1.5 Bolivia 3.4 Kazakhstan 3.4 Slovenia 2.5 Botswana 2.1 Kenya 2.9 Spain 0.3 Brazil 3.1 Kuwait 2.7 Sri Lanka 1.4 Burkina Faso 2.1 Kyrgyzstan 3.5 Switzerland 1.7 Cameroon 2.5 Lao PDR 1.1 Tajikistan 2.3 C. African Rep 2.5 Lebanon 3.3 Tanzania 3.5 Chad 1.6 Lesotho 13 3.1 Thailand 1.5 Chile 3.0 Madagascar 1.4 Tunisia 3.2 China 3.4 Malawi 2.5 Turkmenistan 2.2 Colombia 2.7 Malaysia 1.5 Ukraine 3.8 Congo, D. Rep 1.9 Mali 2.8 United Kingdom 2.9 Costa Rica 3.2 Mauritania 2.5 United States 2.4 Côte d'Ivoire 2.4 Mauritius 2.2 Uruguay 1.9 Dominican Rep 3.4 Mexico 2.9 Uzbekistan 3.6 Egypt 3.4 Mongolia 3.4 Venezuela 0.2 El Salvador 3.2 Mozambique 3.0 Yemen 4.8 Gambia 2.5 Nepal 0.7 Zambia 3.5 Page 6 of 7 WWDR: Development Index Draft of December 2 2001 Histogram of Indicators for Human Development 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 1 2 3 4 5 Bins Figure 1: Presents a frequency histogram of the development scores estimated using the approach presented here. Nations/regions scoring below 3 are less developed than the rest of the regions used to estimate this indicator if the approach proposed here has validity. Page 7 of 7