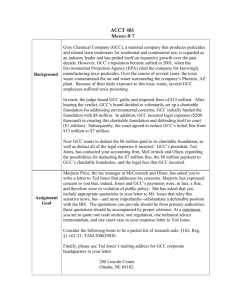

GCC Trade and Investment Flows

advertisement