1 Absolute Advantage and Exchange Rates (assignment) While the

advertisement

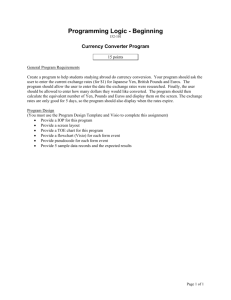

Absolute Advantage and Exchange Rates (assignment) While the theory of absolute advantage in Chapter 2 makes the important point that trade can be beneficial to both importers and exporters, it also begs a number of questions. In particular, although the textbook explains this theory as if Japan and Vietnam use the same currency, this is not the case in reality. Since Japanese rice is priced in yen while Vietnamese rice is priced in dong, a change in the yen/dong exchange rate will affect their relative price and possibly alter which country possesses absolute advantage in rice production. Figure 1 Absolute advantage and the exchange rate Vietnam Japan P P V S’ S J V S P’ V J P P V D’ D Q V D Q Q Figure 1 illustrates how this can happen. Let PV* be the dong price of Vietnamese rice and the exchange be 1 dong = E yen. Then the yen price of Vietnamese rice, PV, is E PV * . An increase in E―the yen’s depreciation―will raise the value of PV, that is, makes Vietnamese rice more expensive in the eyes of Japanese consumers. In Figure 1, the vertical axes of the two diagrams are both measured in yen, so as to make them comparable. In the left panel, therefore, the yen’s depreciation shifts up the demand and supply curves by the same proportion, without changing the equilibrium volume (QV) at 1 which these curves cross each other. However, the equilibrium price is now PV’ yen, which is higher than Japan’s domestic price. Now rice should presumably be exported from Japan to Vietnam. Questions: 1. In general, countries import and export not just one good but a number of products simultaneously. According to our previous analysis, it seems possible that Japan gains an absolute advantage in all goods when the yen depreciates sufficiently vis-à-vis the dong, a possibility that is mentioned in page 28 of the textbook. But is such a situation likely to arise in practice? If it is not, what economic forces prevent it from arising? 2. Although Japan adopts floating exchange rates,1 a number of other countries fix or tightly control the exchange rate of their currencies. For example, according to Figure 2 (see overleaf), China and Vietnam more or less peg their currencies to the US dollar and let their exchange rates adjust only at a snail’s pace.2 If these countries gain an absolute advantage with respect to the United States in all or most goods at the officially determined exchange rate, will their balances of trade remain in surplus indefinitely? Or is there any economic force that will eliminate such trade imbalances even when the Chinese and Vietnamese governments refuse to change the exchange rate? Note that this question is of considerable policy importance―the US government often accuses East Asian countries of manipulating exchange rates to their commercial advantage, a claim denied vehemently by the governments of China and other countries. 1 However, the Japanese government occasionally intervenes in the foreign exchange market to resist the yen’s appreciation. Official exchange market intervention will be a topic in Chapter 16. 2 Note that the Chinese and Vietnamese governments can peg their currencies to the dollar or the yen but cannot peg their currencies to the dollar and the yen simultaneously. If the Vietnamese government chooses to fix the dong to the dollar, the yen/dong exchange rate fluctuates along with the yen/dollar exchange rate and is no longer under the control of the Vietnamese government. 2 Figure 2 Dong/Dollar and RMB/Dollar Exchange Rates 30,000 Dong / USD (lhs) 9 RMB / USD (rhs) 25,000 8 20,000 7 15,000 6 10,000 5 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 (Source) IMF, International Financial Statistics. 3