Measuring Local Institutions and Organizations

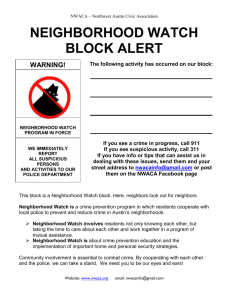

advertisement