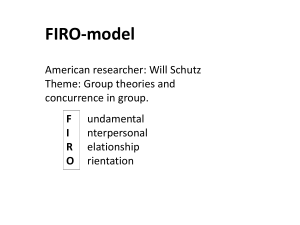

Leadership Impact on Motivation, Cohesiveness and

advertisement