How Much Growth Can Borrowers Sustain

advertisement

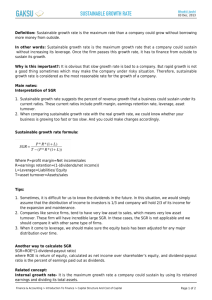

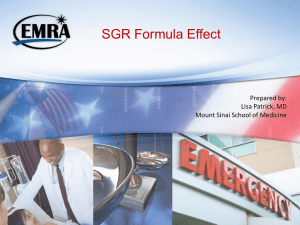

OLDIES, STILL GOODIES The Journal is pleased to reprise articles that are evergreen to the industry. This article made the lenders’ hit parade in 1991. How Much Growth Can Borrowers Sustain? by George W. Kester H ow many times have you been approached by a borrower who is excited about the unlimited sales potential of his or her firm’s products but who needs additional financing to achieve that potential? How many times has the same borrower come back and, instead of repaying the original loan, requested additional financing because the working capital and fixed assets needed to support the sales growth have created a classic situation of being “profit rich and cash poor”? This article explores this dilemma and suggests a method for evaluating how much growth a borrower can sustain. T he situation in which a borrower requests additional financing occurs all too frequently in commercial lending. It occurs for several reasons. One reason is improperly structured loans. The borrower has obtained loans in the form of 90-day notes to finance the permanent increases in working capital associated with sales growth.1 Another reason is that even if a borrower’s working capital is financed through long-term borrowings, continued growth in sales requires additional investments in working capital, thereby necessitating more loans. Eventually, there’s a potentially dangerous situa- tion of too much debt and too little equity. Either additional equity must be obtained or the borrower must reduce the rate of expansion to a level that can be sustained without an increase in financial leverage. Indeed, bankruptcy courts are filled with cases of companies that have expanded themselves right out of business. This article presents a method for evaluating how much growth a borrower can sustain. Such analysis is important for both borrowers and lenders since it determines the level of sales growth that is consistent with the realities of the company and the financial marketplace. © 2002 by RMA; originally published in the June 1991 issue of The Journal of Commercial Bank Lending, published by Robert Morris Associates. At the time, Kester was an associate professor of finance, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, and formerly an officer with First Union National Bank in Charlotte, North Carolina. He is now Martel Professor of Finance, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia. 49 How Much Growth Rate Can Borrowers Sustain? Sustainable Growth Rate The sustainable growth rate (SGR) of a firm is the maximum rate of growth in sales that can be achieved, given the firm’s profitability, asset utilization, and desired dividend payout and debt ratios. If actual sales growth exceeds the SGR, something must give. The firm must become more profitable, utilize its assts more efficiently, or reduce its dividend payout. Otherwise, the firm is faced with the choice of controlling (reducing) its sales expansion or obtaining additional external financing, in the form of additional equity or debt exceeding the desired maximum debt ratio. The latter, of course, could lead to a problem loan situation. To estimate a firm’s SGR, a simple model is described based on the assumption that the future is the same as the past with respect to the firm’s profitability and earnings retention ratio. A simple model. In its simplest form, a firm’s SGR is calculated by multiplying its return on equity by RR—its earnings retention ratio, as seen in the following equation2: SGR Net Profit Beginning Equity RR 1 It is important to note that the firm’s most recent year’s net profit should be divided by its beginning equity—the equity balance at the beginning of the period over which the net profit was earned. An expanded model. It is more instructive and analytically useful to expand the first equation to reflect the components of a firm’s return on equity: asset turnover, profit margin, and financial leverage, as shown below: SGR Sales Beginning Assets Net Profit Sales 1 Debt Equity The RMA Journal July-August 2002 Balance Sheet and Income Statement Data Year 1 Total Assets $3,000 Total Liabilities 1,000 Stockholders’ Equity 2,000 Total $3,000 Sales Net Profit Dividends RR 2 Year 2 $3,300 1,100 2,200 $3,300 $4,000 400 200 Table 2 Variables for Sustainable Growth Rate Calculation Asset Utilization Sales/Beginning Assets = $4,000/$3,000 = Profit Margin Net Profit/Sales - $400/$4,000 Financial Leverage Debt/Equity - $1,000/$2,000 Earnings Retention Ratio (RR) (1 - Dividend Payout) = (1 - $200/$400) 1.33 0.10 0.50 0.50 An example. To illustrate the usefulness and application of the SGR concept, suppose that a company’s abbreviated income statement and balance sheet data are as shown in Table 1, above. Based on these data, Table 2 shows the variables used to calculate the company’s SGR. With these data variables, the sustainable growth rate using the second equation is 10%:3 SGR Sales Beginning Assets SGR As an estimate of future sales growth, the second equation implicitly assumes that the firm’s asset utilization, as measured by its sales-to-beginning-assets ratio, and its profit margin, as measured by its profitto-sales ratio, will remain constant in the future. It is also assumed that the firm’s leverage multiplier, as measured by 1 plus its debt-to-equity ratio, and its earnings retention ratio will remain constant in the future. It is also assumed that no new issues of equity are expected. Based on these assumptions, the first two equations calculate the maximum growth rate in sales that a firm can achieve in the future. 50 Table 1 Net Profit Sales 1 Debt Equity RR [(1.33) (0.10) (10.50)] 0.50 10% Given the company’s asset utilization, profit margin, financial leverage, and earnings retention ratio, the maximum sustainable rate of sales growth that the company can achieve is 10% per year. The result of sales growth of 10% in 3 is shown in Table 3. Table 3 Result of 10% Sales Growth in Year 3 Sales Year 2 Sales x (1 + SGR) - $4,000 x (1.10) = $4,400 Net Profit: Sales x Profit Margin - $4,400 x 0.10 = 440 Earnings Retained: Net Profit x Earnings Retention Ratio - $440 x 0.50 = 220 Assets: Year 2 Assets x (1 + SGR) = $3,300 x 1.10 = 3,630 Shareholders’ Equity: Year 2 Equity + Earnings Retained = $2,200 + $220 = 2,420 Liabilities: Equity x (Debt/Equity Ratio) = $2,420 x 0.50 = 1,210 Total Debt & Equity $3,630 Asset Utilization: Sales/Year 2 Assets = $4,400/$3,300 = 1.33 How Much Growth Rate Can Borrowers Sustain? This example is based on the assumption that the company’s current asset utilization, profit margin, financial leverage, and earnings retention ratio will remain constant in the future. Of course, this may not necessarily be the case. The second equation also can be used to evaluate the effects of changes in one or more of the input variables to the SGR model. For example, assume that due to economies of scale (operating leverage), the company believes that its profit margin will increase to 12% in the future. Also, assume that its asset utilization is expected to improve, with the sales-to-assets ratio increasing to 1.50. If these improvements can indeed be achieved, holding financial leverage and the earnings retention ratio constant, the company’s SGR will increase to 13.5%: SGR [(1.50) (0.12) (1 0.50)] x 0.50 13.5% Let’s assume, however, that due to expected demand for the company’s products, management expects sales growth to be 25%, which exceeds its SGR of 13.5%. In this case, the company is faced with the choice of accepting a lower rate of sales growth, increasing the earnings retention ratio (reducing dividend payout), or obtaining additional external financing. Assume that management is willing to reduce dividends from 50% to 30% of net profit, increasing the earnings retention ratio to 70%. This will increase the SGR to 18.9%, which is still lower than the expected sales growth of 25%: Solving for Other Variables To answer this question, the second equation can be rearranged to solve for the required debt-toequity ratio needed to achieve a target SGR, assuming no changes in the firm’s asset utilization, profit margin, and earnings retention ratio, as follows: Target SGR Net Profit Sales RR Sales Beginning Assets 1 3 Continuing this example, the company’s debt-toequity ratio must increase from 0.50 to 0.98 in order for the company to achieve the expanded sales growth rate of 25%: Required Debt-to-Equity Ratio 0.25 1 0.98 (1.50) (0.12) (0.70) This can be shown by recalculating the company’s SGR using the second equation: SGR [(1.50) (0.12) (1 0.98)] 0.70 25% Of course, a debt-to-equity ratio of 0.98 may not be acceptable to either the company’s management or its lenders, in which case other alternatives must be explored. These alternatives include the often hard-to-swallow prospect that the expected sales growth simply cannot be achieved. The second equation also can be rearranged to solve for the other variables in the SGR model, given a target SGR. The fourth equation calculates the asset utilization needed to achieve a target SGR, assuming no changes in the other variables. SGR [(1.50) (0.12) (1 0.50)] 0.70 18.9% This leaves only two alternatives: Accept a lower growth rate in sales or obtain additional financing. If management is unwilling to accept a lower rate of sales growth and if additional equity is not feasible or desirable, the only alternative left to the firm is to overextend itself by obtaining debt exceeding its desired maximum debt-to-equity ratio, which may be unacceptable to the company’s management or lenders. How much must the debt-to-equity ratio increase to support the expected sales growth rate of 25%? Required Debt-To-Equity Ratio Required Asset Utilization Target SGR Net Profit Sales 1 Debt Equity RR 4 The fifth equation calculates the profit margin required to achieve a target SGR, assuming no changes in the other variables. Required Profit Margin Target SGR Sales Debt 1 Beginning Assets Equity RR 5 And, finally, the sixth equation calculates the earnings retention ratio required to achieve the target SGR, assuming no changes in the other variables. Required Earnings Retention Ratio Target SGR Sales Net Profit Debt 1 Beginning Assets Sales Equity 6 51 How Much Growth Rate Can Borrowers Sustain? Returning to the example, assume that the required debt-to-equity ratio of 0.98 is indeed unacceptable. What level of earnings must be retained for the company to achieve the expected sales growth rate of 25%, assuming the debt-to-equity ratio remains at its current level of 0.50? The earnings retention ratio in the sixth equation must be increased to 92.6%. Retained Earnings Retention Ratio = 0.25 [ (1.50)( 0.12)( 1 0.50) ] 0.926 Sustainable Growth Rate Return on Equity (ROE) 1 Debt Equity Multiplied by Profit Margin Net Income Divided by Total Subtracted Expenses from 52 Cost of Goods Sold Selling and Administrative Expenses Interest Income Taxes Sales The RMA Journal July-August 2002 This can also be shown by recalculating the company’s SGR using the second equation: SGR [ (1.50) (0.12) (10.50) ] 0.926 25% Extending the well-known DuPont chart method of breaking a ratio into its various components, the illustration below shows a graphic depiction of the SGR model reflected in the second equation. This chart demonstrates the effects that various policies and decisions are likely to have on a firm’s SGR. For example, Sustainable the effects of Growth improving asset Rate turnover can easily be traced through the chart to the Retention Multiplied Ratio likely impact on by (1 - Payout) SGR, thus highlighting the importance of effective Return on cash, receivables, Assets (ROA) and inventory management and the efficient utilization of fixed assets. Multiplied Total Asset Turnover by Similarly, the effect of a change in the dividend payout ratio or improved Sales profitability through greater expense control can be traced through Total Divided Sales the chart. Assets by It should be pointed out, however, that changes Current Fixed Plus in one variable may Assets Assets affect one or more variables included in the model. For Marketable example, tighter Cash Securities control of receivables may result in additional expenses Accounts as well as a decline Inventories Receivable in sales. Or an How Much Growth Rate Can Borrowers Sustain? increase in fixed assets to expand capacity, which initially reduces asset turnover, may increase a firm’s expected sales profits. Using the SGR Model in Commercial Lending As should be apparent from the foregoing straightforward examples, the SGR model is simple to use and provides an estimate of the level of sales growth a borrower can achieve, given his or her current or expected asset utilization, profitability, financial leverage, and earnings retention ratio. To the extent that actual or planned sales growth exceeds the estimated SGR, a potential problem loan is in the making. At a minimum, a significant divergence between expected sales growth and the estimated SGR should serve as a warning signal to lenders, prompting further investigation and discussions with the borrower. Using the SGR model provides a convenient means for checking the consistency of the borrower’s growth plans. Borrowers often desire the best of all worlds: high sales growth, low levels of debt, and high dividends. As is often the case, however, these objectives may be inconsistent with each other. And it is certainly better to recognize these inconsistencies before the fact rather than after. Also, illustrated, the SGR model and its variations provide a convenient method of performing sensitivity analysis on the key variables that affect a company’s sales growth. What improvements are necessary in the company’s asset utilization or profitability to achieve the desired or expected level of sales growth? What level of debt is required, and is it acceptable to the borrower and its lenders? Can the expected or desired level of sales growth be realistically attained, given the constraints placed on the company? Conclusion In short, the SGR model can be a valuable tool for commercial lenders in assessing their borrower’s ability to plan for and manage growth in a financially sound manner. Lenders must be comfortable that their borrowers understand that a business cannot just continue to expand without making adequate plans for financing that growth. Otherwise, borrowers and lenders are faced with the perpetual problem of continuous requests for renewals and additional loans. ❐ Notes 1 See George W. Kester and Thomas W. Bixler, “Why 90-Day Working Capital Loans Are Not Repaid on Time,” The Journal of Commercial Bank Lending, August 1990, for a discussion of permanent and temporary working capital. 2 This model is derived from a more elaborate model developed by Robert C. Higgins, “How Much Growth Can a Firm Afford?” Financial Management, Fall 1977. Also see Robert C. Higgins, “Sustainable Growth Under Inflation,” Financial Management, Autumn 1981, and Dana J. Johnson, “The Behavior of Financial Structure and Sustainable Growth in an Inflationary Environment,” Financial Management, Autumn 1981. 3 The same results can be obtained by using the first equation: SGR SGR Net Profit Beginning Equity $400 $2,000 RR 0.50 10% Moving? Make sure the Journal is there when you are! Please affix your current label, fill in your new address below, and fax to Customer Relations, 215-446-4101. New address:________________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 53