Reliability and Validity of Current Physical Examination Techniques

advertisement

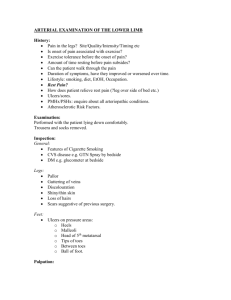

ORIGINAL ARTICLES Reliability and Validity of Current Physical Examination Techniques of the Foot and Ankle James S. Wrobel, DPM, MS* David G. Armstrong, DPM, PhD* Background: This literature review was undertaken to evaluate the reliability and validity of the orthopedic, neurologic, and vascular examination of the foot and ankle. Methods: We searched PubMed—the US National Library of Medicine’s database of biomedical citations—and abstracts for relevant publications from 1966 to 2006. We also searched the bibliographies of the retrieved articles. We identified 35 articles to review. For discussion purposes, we used reliability interpretation guidelines proposed by others. For the κ statistic that calculates reliability for dichotomous (eg, yes or no) measures, reliability was defined as moderate (0.4–0.6), substantial (0.6–0.8), and outstanding (> 0.8). For the intraclass correlation coefficient that calculates reliability for continuous (eg, degrees of motion) measures, reliability was defined as good (> 0.75), moderate (0.5–0.75), and poor (< 0.5). Results: Intraclass correlations, based on the various examinations performed, varied widely. The range was from 0.08 to 0.98, depending on the examination performed. Concurrent and predictive validity ranged from poor to good. Conclusions: Although hundreds of articles exist describing various methods of lowerextremity assessment, few rigorously assess the measurement properties. This information can be used both by the discerning clinician in the art of clinical examination and by the scientist in the measurement properties of reproducibility and validity. (J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 98(3): 197-206, 2008) Foot problems are common, complex, and costly. Estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey suggest that the prevalence of significant mobility problems in the United States affects more than one in six adults.1 This figure increases to nearly one in three for persons aged 60 years old or older. Lower-extremity maladies play a central role in these problems and have a substantial impact on quality of life and self-efficacy. Interest in the treatment of the lower extremity has yielded a host of proposed measurements and examination techniques designed to better quantify the degree of pathology. However, there has been comparatively little attention given to robust inquiry into the reliability and validity of these techniques. *Scholl’s Center for Lower Extremity Ambulatory Research, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, Chicago, IL. Corresponding author: James S. Wrobel, DPM, MS, Center for Lower Extremity Ambulatory Research, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, 3333 Green Bay Rd, North Chicago, IL 60064. (E-mail: james.wrobel@rosalindfranklin.edu) With this structured literature review we sought to evaluate aspects of the orthopedic, neurologic, and vascular examination of the foot and ankle. Methods We conducted a systematic literature search with PubMed—the US National Library of Medicine’s online database of biomedical citations—and searched abstracts available on the Internet. PubMed includes 16 million citations from more than 4,800 journals published in the United States and more than 70 other countries, primarily since 1966. We searched for foot exam and reliability, accuracy, or validity. Criteria for inclusion included a well-described patient population and sampling technique. The examiner description and training had to be well described, and the examination technique had to be described well enough to be reproduced in a typical clinical setting. Additional inclusion criteria included valid statistical techniques and presentation of the data. With these inclusion criteria, 27 studies were included Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association • Vol 98 • No 3 • May/June 2008 197 from 133 potential studies for reliability, 19 studies were included from 120 potential studies for accuracy, and for validity, 5 studies were included from 75 potential studies. The searching sequence (reliability followed by accuracy followed by validity) affected our yield because studies with more than one search term were grouped under the first term searched and found. Relevant references from the included studies’ bibliographies were also considered for inclusion. Of the 51 included studies, findings from 38 studies are reported here. Both authors had complete access to the articles and met to agree for inclusion or exclusion of various studies. Reliability can take on many forms depending on the measure and its purpose. These include test-retest reliability and interitem consistency from the psychometric literature. Test-retest reliability tests concepts at different points in time when the underlying condition is not expected to change. Reliable items exhibit similar scores over this period. Interitem consistency tests the correlation of items within a conceptual domain to see if they agree with the overall concept. From the clinical perspective, reliability is commonly measured with intrarater reliability and interrater reliability form. Validity from the clinical perspective is commonly measured with predictive, criterion-related, and face validity.2 Predictive validity successfully predicts an outcome of interest. A prediction is sensitive if it detects differences important to the investigator. It is specific if it represents only the characteristic of interest. Criterion validity agrees with other approaches. Face or content validity makes intuitive sense.2 For measures of reliability, many advocate avoiding arbitrary cutoff points for the measures. For the purposes of our discussion, we used interpretation guidelines proposed by others so we could describe the current state of the foot examination measures. For the κ statistic that calculates reliability for dichotomous (eg, yes or no) measures, reliability was defined as moderate (0.4–0.6), substantial (0.6–0.8), and outstanding (> 0.8).3 For the intraclass correlation coefficient that calculates reliability for continuous (eg, degrees of motion) measures, reliability was defined as good (> 0.75), moderate (0.5–0.75), and poor (< 0.5).4 The SEM can roughly be interpreted as the number by which examiners will tend to vary. Results The previously defined search criteria resulted in the inclusion of 38 manuscripts described in Table 1. The table divides the studies into the type of examination performed, the number of examiners, the basic method 198 of examination, the reliability, and the investigators’ conclusions. Intraclass correlations on the basis of the various examinations performed varied widely. The range was from 0.08 to 0.98, depending on the examination performed. Discussion Orthopedic Examination The orthopedic examination was the most studied area of the clinical aspect representing 26 of 38 articles.5-25, 36-40 Visual estimation of the forefoot-to-rearfoot ratio may be more reliable than an estimate made with a goniometer. In a study of ten patients,11 examiner experience with the two methods did not seem to matter. The interrater reliability was poor with the goniometer and good with visual estimation. Conversely, measuring first-ray mobility as normal, hypomobile, or hypermobile with qualitative methods (n = 60)9 showed poor interrater reliability, as did using a ruler (n = 14)10 with a Glasoe device as the standard. Range-of-motion testing appears to demonstrate good reliability.5, 6, 8 In a study of 63 healthy Navy midshipmen, both active and passive range of ankle dorsiflexion was measured in the prone position. This method revealed a good intrarater reliability and moderate inter-examiner reliability with mean absolute differences of 2° and 3°.5 These numbers compare favorably with a previous report, in which ankle dorsiflexion was measured in the supine position.8 Elveru et al6 investigated the reliability of ankle and subtalar joint motion for 50 patients of 14 physical therapists. They found ankle joint motion to have good intrarater reliability; however, subtalar joint positions and neutral were found to have poor reliability. Moderate interrater reliability was found with ankle motion. The authors also stated that the therapists had little or no experience in assessing a subtalar joint.6 When first metatarsophalangeal joint motion was measured in a weightbearing position, the average error found was 12° and 16° in the dorsiflexed and plantarflexed positions, respectively.7 This finding contradicts subsequent work that found good interrater reliability in first metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion measured in a weightbearing position.8 Different examination methods could partially explain the findings; patients were asked to stand with one foot on the edge of a stool7 and on the floor in a relaxed, bipedal stance. This difference in technique may have added to the observed reliability differences.8 Manual muscle testing, including the supination resistance test, appears to demonstrate good reliability May/June 2008 • Vol 98 • No 3 • Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association Table 1. Reliability and Validity of Lower-Extremity Examination Method by Examination Technique Examination Technique Sample Size and Examiner Type Method Reliability and Validity Author’s Conclusion Orthopedic Examination Ankle dorsiflexion, leg length discrepancy, medial talonavicular bulge, rearfoot angle, arch angle and foot type5 n = 63 Navy midshipmen; physical therapy and athletic trainer examiners ICC = 0.65–0.97 with 88.8%–94.4% agreement Results reliable when conducted on healthy individuals Ankle and subtalar joint motion6 n = 50; 15 physical therapist examiners Intrarater ICC 0.74 for ankle; Intertester ICC: STJ inversion = 0.32, STJ eversion = 0.17, STJ neutral = 0.25, and 0.50 and 0.72 for ankle With the exception of ankle plantarflexion, measures cannot be considered reliable First metatarsophalangeal joint mobility7 n = 20 Dorsiflexion and plantarflexion Average error = 12˚ (dorsiflexion) and 16˚ plantarflexion Linear measurement more accurate than angular Ankle and first metatarsophalangeal joint mobility8 n = 10; two podiatrist examiners Supine ankle dorsiflexion and weightbearing first metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion Interrater reliability was 0.71 for ankle and 0.95 for first metatarsophalangeal joint Good reliability for ankle and first metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion First-ray mobility9 n = 60; three clinician examiners Normal, hypomobility, and hypermobility versus Glasoe device Interrater κ statistic = Poor agreement 0.143 for hypomobility (30% agreement); 0.063 for normal (34% agreement); not calculated for hypermobility (25% agreement) First-ray mobility 10 n = 14; three clinician examiners Ruler versus mechanical device Device ICC = 0.98 (SEM = 0.15 mm) Ruler intratest ICC = –0.06 (SEM = 1.1 mm) Ruler intertest ICC = 0.05 (SEM = 1.2 mm) Poor reliability for ruler method Ball circumference7 n = 20 Average measurement error = 1.1 cm Linear measurement more accurate than angular Forefoot-to-rearfoot assessment11 n = 10; two physical therapists and two student examiners Intrarater goniometer ICC of 0.08 to 0.78 Intrarater visual ICC of 0.51 to 0.76 Interrater goniometer = 0.38 Interrater visual = 0.81 Visual estimation may be more reliable κ statistics very good (0.61–1); however, when normals excluded, κ statistics were 0.55 to 0.88 (direct agreement, 11%–41%) Reliability could be improved with training. Only use manual muscle testing in pathology if agreement > 80% Manual muscle testing12 n = 72, three examiners Visual and goniometer continued on next page Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association • Vol 98 • No 3 • May/June 2008 199 Table 1. continued Examination Technique Sample Size and Examiner Type Method Reliability and Validity Author’s Conclusion Orthopedic Examination (continued) Manual supination resistance test13 n = 44; four clinician examiners on 2 days Test-retest reliability; interrater ICC = 0.89, intrarater ICC of 0.78 to 0.82, two inexperienced clinicians’ ICC of 0.56 to 0.62 (poor) Supination resistance test may be clinically useful in prescription orthoses Ankle laxity, stability, and strength14 n = 21 Correlation (r ) > .75 High correlation suggests reliability Foot type15 n = 20 SAI, CSI, and NH to represent foot type by calcaneal alignment as tested with footprint and changes in alignment over five test positions SAI r = .5, CSI r =.6, NH r = .8. Change in degrees required to see change in index score, 20 for SAI, 15 for CSI, and 10 for NH NH more sensitive to change and thus had a greater sensitivity to changes in calcaneal position Medial arch16 n = 51 Five measures taken at 10% weightbearing and 90% weightbearing Concurrent validity with radiographs; dorsum height at 50% of foot length divided by truncated foot length (ICC = 0.81 for 10% and 0.85 for 90%) The most reliable and valid was arch height at 10% and 90% weightbearing, dividing dorsum height at 50% of foot length by truncated foot length Resting calcaneal stance position17 n = 88 adults; n = 124 children Adults = 6˚ everted (SD = 2.71) Children = 5.6˚ everted (SD = 2.9) Resting calcaneal stance position was reliable; however, theoretical normal of 0 ± 2˚ not observed Limb-length discrepancy18 n = 66 with 17 examiners 0.5-cm boards for indirect measurement with orthoradiograms as standard Concurrent validity; 81% differed by 0–1.0 cm. No differences amongst experience Indirect limb-length measurement accurate; experience played no role Arch index, NH, FPI19 n = 95 Correlated with radiographs: NH, calcaneal inclination angle, and first metatarsalcalcaneal angle Concurrent validity with x-ray positions (pronated, neutral, and supinated). NH r = .44, .53, .79; arch index r = .71, –.68, .52; FPI r = .59, .36, .42 All methods provide valuable information about medial longitudinal arch; NH most useful clinical measure FPI20 n = 29 children; n = 30 adolescents; n = 30 adults ICC children = 0.62, adolescents = 0.74, adults = 0.58; measurement error 1–1.5 points on 33-point scale Reliability moderate to good FPI21 n = 20 Four-phase validation study of concurrent and predictive validity; sixitem FPI predicted more than 40% of variance ankle joint complex Stronger association than most reports of static and dynamic measures Derived measures from 119 papers; item reduction; six items compared with static and dynamic electromagnetic motiontracking system continued on next page 200 May/June 2008 • Vol 98 • No 3 • Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association Table 1. continued Examination Technique Sample Size and Examiner Type Method Reliability and Validity Author’s Conclusion Orthopedic Examination (continued) FPI22 Study 1: n = 31 Study 2: n = 12 Criterion validity of four criteria for FPI with radiographic criteria as standard Correlations poor (–0.28 to 0.42); talonavicular angle significant; significant changes from supinated to resting position and from supinated to pronated Criterion validity weaker than expected although significant correlation and change with foot manipulation for talar head palpation Observational gait scale23 n = 20; two clinician examiners Knee and foot position at mid-stance; base of support and rearfoot position with video Intratest-weighted κ statistic, 0.53–0.91 Intertest-weighted κ statistic, 0.43–0.86 Base and rearfoot ranges, 0.29–0.71 (intratest), 0.3–0.78 (intertest) Angle and base of gait24 n = 25 Angle and base of gait measured with footprints and clinical tracings ICC of 0.97–0.98 for angle and 0.98–0.99 for base of gait Data similar; both are useful clinical tools One-legged stance25 n = 10 Rearfoot motion STJ neutral, maximum eversion, maximum inversion Concurrent validity with electrogoniometer; ICC of 0.76, 0.37, 0.39, respectively; intratest ICC of one-legged stance = 0.92 Good interrater reliability for STJ neutral; rearfoot position one-legged stance may be used to approximate maximum eversion during gait Sensitivity, 80%; specificity, 90% Although small study, toe response at time of foot exposure frequently provides evidence of pyramidal tract dysfunction Disagreed in 18 of 145 fair intertester reliability κ statistics = 0.73; disagreement associated with age Self-administered sensory tests allow patients to participate in care but should not replace provider exam Neurologic Examination “Bedsheet” Babinski26 n = 20; 10 with neurologic disease and 10 without Patient use of monofilament27 n = 196 Nine centers, same-day self-screen and clinician examiner Thermal sensitivity and VPT28 n = 39 Babinski29 n = 10 (8 with upper motor neuron lesion); 10 physician examiners Toe response at the time feet are exposed Reliability coefficient for ICC of 0.89 (VPT) thermal sensitivity and and 0.54 (thermal VPT sensitivity) Babinski κ statistic fair (0.3); toe-tapping κ statistic substantial (0.73) Babinski agreement = 56%; toe–tapping agreement = 85% Reproducible VPT is inversely proportional to age and better for men Ability of Babinski sign to identify upper motor neuron lesion is limited. Slowness of toe tapping may be more useful sign continued on next page Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association • Vol 98 • No 3 • May/June 2008 201 Table 1. continued Examination Technique Sample Size and Examiner Type Method Reliability and Validity Author’s Conclusion Neurologic Examination (continued) Monofilament, ankle reflexes, pinprick, vibration, position30 n = 304; ten centers of internist and resident examiners Monofilament and ankle reflex κ statistic moderate (0.59); pinprick, vibration, and position κ statistics fair (0.28–0.36) Conventional clinical exam of diabetes mellitus feet had low reproducibility and correlated poorly with monofilament. Monofilament was reproducible, valid, and the procedure of choice Vascular Examination Pedal pulse palpation31 n = 100 63% had systolic diastolic pressure ≥ 118 mmHG; 68% had ABI > 0.82; Predition ankle systolic sensitivity (66%) and specificity (91%) Palpable pulse suggests ankle systolic pressure ≥ 118 mmHG and ABI > 0.82 Pedal pulse palpation32 n = 229 Test-retest reliability; range of reproducibility = 68%–81% for all four pulses Unacceptable variation with monofilament the best screening tool Pedal pulse palpation33 n = 25; three vascular surgeon and three student examiners κ statistics highest in vascular techs (0.68, good), vascular surgeons (0.38, fair). Best cutoff for ABI between palpable and nonpalpable = 0.76 underdiagnosed 30% Pulses palpated under unhurried conditions; acceptable reproducibility and accuracy ABI34 n = 246 ABI measured with continuous-wave Doppler versus automated oscillometry Concurrent validity with standard ultrasound; ankle systolic mean difference 2 mmHG (± 6.7); 3.1 mmHG (± 5.1 mmHG) Both methods fell within 1% error and 5% reproducibility ABI35 n = 201 ABI measured with continuous-wave Doppler versus automated oscillometry Concurrent validity with standard ultrasound; correlation coefficient 0.78; mean difference 0.04 (± 0.01) and 0.06 (± 0.01) Automated ABI reliable Abbreviations: ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; STJ, subtalar joint; SAI, Staheli arch index; CSI, Chippaux-Smirak index; NH, navicular height; FPI, foot posture index; VPT, vibratory perception threshold; ABI, ankle-brachial index. Note: Intertest refers to reliability among examiners on same patient. Intratest refers to reliability for the same examiner and patient at different points in time. 202 May/June 2008 • Vol 98 • No 3 • Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association when used by experienced clinicians.12-14, 39 Ankle ligamentous laxity also appears to demonstrate good reliability.14 Relaxed calcaneal stance position appears to demonstrate good reliability. In a study of 212 patients with a two-arm goniometer and an electronic goniometer, the greatest mean difference within examiners (intrarater) was 0.5°. Among examiners (interrater) the greatest mean difference was 1.23° for the twoarm goniometer.17 Torburn et al25 further assessed the reliability of rearfoot measures in ten patients. They found that subtalar joint neutral position demonstrated good reliability and that a relaxed, one-legged stance was not significantly different from the observed rearfoot eversion during gait.25 Other weightbearing measures demonstrated good reliability.5, 9, 13, 14 These measures include angle and base of gait, and limb-length discrepancy with a 0.5cm board. Observational gait analysis was studied in 14 patients with a three-point scale assessing rearfoot motion and was found to have poor reliability.38 In a subsequent observational gait scale study of 20 patients, investigators found acceptable reliability for the foot position in mid-stance, initial foot contact, and heel rise with weighted κ statistics ranging from 0.53 to 0.91 (intrarater) and 0.43 to 0.86 (interrater).23 The orthopedic examination is one of the most utilized in clinical podiatric practice. With the exception of one study (Resch et al7), range-of-motion testing at the ankle, subtalar joint, and first metatarsophalangeal joint seems to exhibit good to moderate intrarater reliability.5, 6, 8, 17, 25 The reliability of subtalar joint range of motion testing may be enhanced with additional training.6 Visual estimation of the forefootto-rearfoot relationship demonstrates good interrater reliability over goniometer or stratifying first ray into hypomobility, normal, or hypermobility.9, 11 Manual muscle testing and ankle stability appear to demonstrate good interrater reliability.12-14, 39 Assessing limblength discrepancy with boards and some aspects of visual gait analysis demonstrates good interrater reliability.5, 18, 23 Clinical measures for foot type and standing arch postures are two of the most studied areas of the orthopedic examination.15, 16, 19-22, 37 In general, these have been described in three categories: radiographic, anthropometric, and footprint measures.40 Mathieson et al15 studied various footprint measures in 20 patients positioned in five standardized positions. They investigated three foot type measures: the Staheli arch index, the Chippaux-Smirak index, and navicular height. The investigators examined the sensitivity of the three foot type measures to detect alterations in subtalar joint position as measured by calcaneal frontal plane alignment.15 The Staheli arch index and Chippaux-Smirak index demonstrated moderate reliability, and navicular height demonstrated good reliability. Change required to observe a change in index score include 15° for Chippaux-Smirak index, 20° for Staheli arch index, and 10° for navicular height. Navicular height was more sensitive to change and thus had a greater sensitivity to changes in calcaneal position. Mathieson et al15 concluded that foot type measures derived from a static footprint exhibit limited responsiveness to changes in subtalar joint position. Anthropometric measures of foot type are probably the most clinically useful. Arch height has received much attention in the earlier literature. Williams and McClay16 looked at five measurements of arch height taken in two stance conditions, 10% and 90% weightbearing, in 51 patients. Reliability was good for dorsum height at 50% of foot length divided by truncated foot length (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.81 for 10% weightbearing and 0.85 for 90% weightbearing). Dividing the dorsum height at 50% of foot length by the truncated foot length was the most reliable and valid of the five measures tested to clinically assess arch height at the two stances.16 Menz and Munteanu19 performed a concurrent validity study on 95 patients measuring navicular height, arch index, and foot posture index. They correlated these measures with radiographic angles of calcaneal inclination, calcaneal first metatarsal declination, and navicular height. They found that all three measures demonstrated significant correlations with the radiographic measures. The authors concluded that the three measures provided useful, but different, information about arch structure. Navicular height was believed to be most clinically useful because of its higher concurrent validity and low technical difficulty.19 One of the most studied anthropometric measures for foot type is the foot posture index.19-22 The original description attributed to Redmond21 consisted of eight criteria of talar head palpation, supralateral and infralateral malleolar curvature, Helbing sign, calcaneal frontal plane position, prominent talonavicular joint, congruence of the medial longitudinal arch, congruence of the lateral border of the foot, and abduction and adduction of the forefoot on the rearfoot. Each criterion is graded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from –2 to 2.20, Evans et al20 went on to study inter- and intrarater reliability of the foot posture index in children (n = 29), adolescents (n = 30), and adults (n = 30) with four raters. Normalized navicular height was the most reliable measure, except in children. Navicular drop, relaxed calcaneal stance position, and neutral calcaneal stance position demonstrated moderate to poor reliability. Forefoot-to-rearfoot relationship was moderate to poor but improved as Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association • Vol 98 • No 3 • May/June 2008 203 the patient group became older. The SEM was 2°, which is high for the range of measures but favorable compared with the other measures. None of the measures exhibited adequate reliability in children.20 The foot posture index underwent further criterion validity testing with radiographic measures as the standard in 31 patients.22 Correlations with radiographs were generally poor (–0.28 to 0.42), although the talonavicular angle was significant. The responsiveness of the foot posture index was seen with significant changes from supinated to resting position and from supinated to pronated position. The authors concluded that criterion validity (with radiographic measures) was weaker than expected, although significant correlation and change with foot manipulation for talar head palpation was observed.22 The foot posture index was also studied for criterion validity with static and dynamic data from an electromagnetic motion analysis system and was able to predict 40% of the variance in dynamic ankle motion with walking.21 The authors studied 91 patients in the item-reduction phase, resulting in six of the eight original items being retained in the model (talar head palpation, supralateral and infralateral malleolar curvature, calcaneal frontal plane position, prominent talonavicular joint, congruence of the medial longitudinal arch, and abduction and adduction of the forefoot on the rearfoot). Twelve patients were then analyzed for the predictive validity phase with static and dynamic weightbearing. The six-item foot posture index was able to predict 40% of the variance in dynamic ankle motion with walking.21 The amount of variance described is higher than previous reports that describe static clinical measures predicting dynamic function.8 Foot type and standing arch postures appear to be used more for research purposes, rather than clinical care, and thus demand a higher level of reliability and validity. Navicular height demonstrated good reliability and more responsiveness to rearfoot change over the Staheli arch index and the Chippaux-Smirak index.15 The most reliable and valid measure of arch height at 10% and 90% weightbearing stances was obtained by dividing the dorsum height at 50% of foot length by the truncated foot length.16 Neurologic Examination Several studies have investigated the reliability of the neurologic examination.12, 26-30, 39 Miller and Johnston29 observed ten patients and found the Babinski sign to have fair interrater reliability for five neurologists and five primary-care providers. Decreased speed of toe tapping had better reliability and agreement for identifying patients with an upper motor neuron lesion.29 204 Berger and Fannin26 also studied 20 inpatients and found the “bedsheet Babinski” had high sensitivity and specificity for detecting patients with neurological disease. Brandsma et al12 studied 72 patients with manual muscle testing. The interrater reliability was substantial to excellent. However, when normals were excluded, the interrater reliability was reduced to moderate to substantial levels.12 Smieja et al30 studied the interrater reliability of pinprick, vibration, deep tendon reflexes, position sensation, and monofilament testing in 304 patients in ten centers with internists and residents. They found the monofilament and ankle reflex examinations to have moderate reliability. The pinprick, vibration, and position sense examinations had fair reliability.30 Birke and Rolfsen27 studied the interrater reliability of the monofilament examination on 196 patients at nine centers and also found it to have substantial reliability.30 De Neeling et al28 studied the test-retest intrarater reliability of thermal and vibratory perception threshold examination in 39 patients and found good reliability with thermal sensitivity demonstrating moderate reliability. The neurologic examination demonstrated good test-retest reliability for vibratory perception threshold; moderate for thermal testing; and fair with pinprick, vibratory, and joint position testing.28, 30 Monofilament and ankle reflex testing demonstrated moderate reliability.27, 30 For predictive validity of upper motor neuron lesion, slowness of toe tapping had better interrater reliability and, along with the “bedsheet Babinski,” may predict disease better than the traditional Babinski sign.26, 29 Vascular Examination In the vascular examination, pedal pulse palpation and ankle-brachial index were the most studied examinations for reliability.31-35 Lundin et al33 studied interrater reliability of pedal pulse palpation for vascular surgeons and students in 25 patients. They found vascular technicians to have substantial reliability and vascular surgeons to have fair reliability. The differences in results were attributed to hurried clinical conditions. Klenerman et al32 also found substantial test-retest intrarater reliability in pulse palpation in 229 patients studied. Raines et al34 (n = 246) and Beckman et al35 (n = 201) studied automated oscillometry for calculating ankle-brachial indexes and found the methods to be reliable. When looking at pedal pulse palpation, it seems the best cutoff for ankle-brachial index would range from 0.76 to 0.82.31, 33 These findings suggest there is a reservoir of peripheral arterial disease undetected by physical examination that might benefit from referral back to primary May/June 2008 • Vol 98 • No 3 • Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association care should medical management not be optimal.41 Pedal pulse palpation demonstrated substantial reliability depending on clinician type and hurried clinical conditions.32, 33, 42 We have attempted to describe the reliability and validity of current foot examination. We understand that the needs of the examination may differ on the basis of application (clinical or research). Although hundreds of articles describe various methods of lower-extremity assessment, few have given rigorous attention to these measurement properties. We hope that future works in this area will include these critical measures to better guide the clinician in selecting examinations that can accurately assess the functional and physiological status of the lower extremity. The discerning clinician can then use this information to strike the delicate balance between the art of clinical examination and the science of reproducibility and validity. Financial Disclosures: None reported. Conflict of Interest: None reported. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. References 1. CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION: Mobility limitation among persons aged ≥40 years with and without diagnosed diabetes and lower extremity disease, United States, 1999-2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 54: 1183, 2005. 2. H ULLEY SB, C UMMINGS SR ( ED ): Designing Clinical Research, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1988. 3. L ANDIS JR, KOCH GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33: 159, 1977. 4. PORTNEY LG, WATKINS MP: “Statistical Measures of Reliability,” in Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice, ed by LG Portney and MP Watkins, p 505, Appleton and Lange, Norwalk, CT, 1993. 5. JONSON SR, GROSS MT: Intraexaminer reliability, interexaminer reliability, and mean values for nine lower extremity skeletal measures in healthy naval midshipmen. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25: 253, 1997. 6. E LVERU RA, R OTHSTEIN JM, L AMB RL: Goniometric reliability in a clinical setting. Subtalar and ankle joint measurements. Phys Ther 68: 672, 1988. 7. R ESCH S, RYD L, S TENSTRÖM A, ET AL : Measuring hallux valgus: a comparison of conventional radiography and clinical parameters with regard to measurement accuracy. Foot Ankle Int 16: 267, 1995. 8. W ROBEL JS, C ONNOLLY JE, B EACH ML: Associations between static and functional measures of joint function in the foot and ankle. JAPMA 94: 535, 2004. 9. C ORNWALL MW, F ISHCO WD, M C P OIL TG, ET AL : Reliability and validity of clinically assessing first-ray mobility of the foot. JAPMA 94: 470, 2004. 10. GLASOE WM, GETSOIAN S, MYERS M, ET AL: Criterion-related validity of a clinical measure of dorsal first ray mobility. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 35: 589, 2005. 11. SOMERS DL, HANSON JA, KEDZIERSKI CM, ET AL: The influence of experience on the reliability of goniometric and 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. visual measurement of forefoot position. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25: 192, 1997. BRANDSMA JW, VAN BRAKEL WH, ANDERSON AM, ET AL: Intertester reliability of manual muscle strength testing in leprosy patients. Lepr Rev 69: 257, 1998. NOAKES H PAYNE C: The reliability of the manual supination resistance test. JAPMA 93: 185, 2003. B AUMHAUER JF, A LOSA DM, R ENSTRÖM AF, ET AL : Testretest reliability of ankle injury risk factors. Am J Sports Med 23: 571, 1995. MATHIESON I, UPTON D, PRIOR TD: Examining the validity of selected measures of foot type: a preliminary study. JAPMA 94: 275, 2004. WILLIAMS DS, MCCLAY IS: Measurements used to characterize the foot and the medial longitudinal arch: reliability and validity. Phys Ther 80: 864, 2000. SOBEL E, LEVITZ SJ, CASELLI MA, ET AL: Reevaluation of the relaxed calcaneal stance position. Reliability and normal values in children and adults. JAPMA 89: 258, 1999. PAKVIS DF, JAARSMA RL, VAN KAMPEN A: Limb-length measurements using wooden boards: an accurate and experienceindependent method [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 147: 443, 2003. MENZ HB, MUNTEANU SE: Validity of 3 clinical techniques for the measurement of static foot posture in older people. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 35: 479, 2005. EVANS AM, COPPER AW, SCHARFBILLIG RW, ET AL: Reliability of the foot posture index and traditional measures of foot position. JAPMA 93: 203, 2003. REDMOND AC, CROSBIE J, OUVRIER RA: Development and validation of a novel rating system for scoring standing foot posture: the Foot Posture Index. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 21: 89, 2006. SCHARFBILLIG R, EVANS AM, COPPER AW, ET AL: Criterion validation of four criteria of the foot posture index. JAPMA 94: 31, 2004. MACKEY AH, LOBB GL, WALT SE, ET AL: Reliability and validity of the Observational Gait Scale in children with spastic diplegia. Dev Med Child Neurol 45: 4, 2003. C URRAN SA, U PTON D, L EARMONTH ID: Quantifying the quasi-static angle and base of gait: a preliminary investigation comparing footprints and a clinical method. JAPMA 96: 125, 2006. T ORBURN L, P ERRY J, G RONLEY JK: Assessment of rearfoot motion: passive positioning, one-legged standing, gait. Foot Ankle Int 19: 688, 1998. B ERGER JR, FANNIN M: The “bedsheet” Babinski. South Med J 95: 1178, 2002. BIRKE JA, ROLFSEN RJ: Evaluation of a self-administered sensory testing tool to identify patients at risk of diabetesrelated foot problems. Diabetes Care 21: 23, 1998. DE N EELING JN, B EKS PJ, B ERTELSMANN FW, ET AL : Sensory thresholds in older adults: reproducibility and reference values. Muscle Nerve 17: 454, 1994. M ILLER TM, J OHNSTON SC: Should the Babinski sign be part of the routine neurologic examination? Neurology 65: 1165, 2005. SMIEJA M, HUNT DL, EDELMAN D, ET AL: Clinical examination for the detection of protective sensation in the feet of diabetic patients. International Cooperative Group for Clinical Examination Research. J Gen Intern Med 14: 418, 1999. KAZMERS A, KOSKI ME, G ROEHN H, ET AL: Assessment of noninvasive lower extremity arterial testing versus pulse Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association • Vol 98 • No 3 • May/June 2008 205 exam. Am Surg 62: 315, 1996. 32. KLENERMAN L, MCCABE C, COGLEY D, ET AL: Screening for patients at risk of diabetic foot ulceration in a general diabetic outpatient clinic. Diabet Med 13: 561, 1996. 33. L UNDIN M, W IKSTEN JP, P ERÄKYLÄ T, ET AL : Distal pulse palpation: is it reliable? World J Surg 23: 252, 1999. 34. RAINES JK, FARRAR J, NOICELY K: Ankle/Brachial index in the primary care setting. Vasc Endovascular Surg 38: 131, 2004. 35. BECKMAN JA, HIGGINS CO, GERHARD-HERMAN M: Automated oscillometric determination of the ankle-brachial index provides accuracy necessary for office practice. Hypertension 47: 35, 2006. 36. B AKER CP, NEWSTEAD AH, MOSSBERG KA, ET AL: Reliability of static standing balance in nondisabled children: comparison of two methods of measurement. Pediatr Rehabil 2: 15, 1998. 206 37. MENZ HB: Alternative techniques for the clinical assessment of foot pronation. JAPMA 88: 119, 1998. 38. K EENAN AM, B ACH TM: Video assessment of rearfoot movements during walking: a reliability study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 77: 651, 1996. 39. B ARR AE, D IAMOND BE, WADE CK, ET AL : Reliability of testing measures in Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 72: 315, 1991. 40. C OWAN DN, R OBINSON JR, J ONES BH, ET AL : Consistency of visual assessments of arch height among clinicians. Foot Ankle Int 15: 213, 1994. 41. AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION: Peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care 26: 3333, 2003. 42. EDELMAN D, SANDERS LJ, POGACH L: Reproducibility and accuracy among primary care providers of a screening examination for foot ulcer risk among diabetic patients. Prev Med 27: 274, 1998. May/June 2008 • Vol 98 • No 3 • Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association