Environmental History, Legislation, and Economics

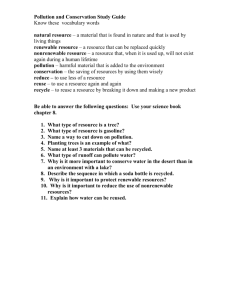

advertisement