SITUATIONAL LEADERSHIP

There is currently a consensus among social and behavioural scientists that leadership skills and competencies

are not inherited from one’s ancestors, that they do not magically appear when a person is assigned to a

leadership position, and that the same set of competencies will not provide adequate leadership in every

situation. Different situations require different approaches to leadership. The following provides what we

consider to be one of the major and dominate theories that explores the dynamics of leadership styles and

adaptation.

The Theory of Situational Leadership was developed by Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard (1977) where

they concluded that they can classify most of the activities of leaders into two distinct behavioural

dimensions: initiation of structure (task actions) and considerations of group members (relationships of

maintenance actions). They defined task behaviour as the extent to which a leader engages in one-way

communication by explaining what each follower is to do as well as when, where, and how tasks are to be

accomplished. They define relationship behaviour as the extent to which a leader engages in tow-way

communication by providing emotional support and facilitating behaviours. The research has discovered that

some people are strong in one area and neglect the other, others are well balanced and some neglect both

leadership dimensions. It is however important to recognize the equal importance of all roles within each

dimension to optimal ream or group management.

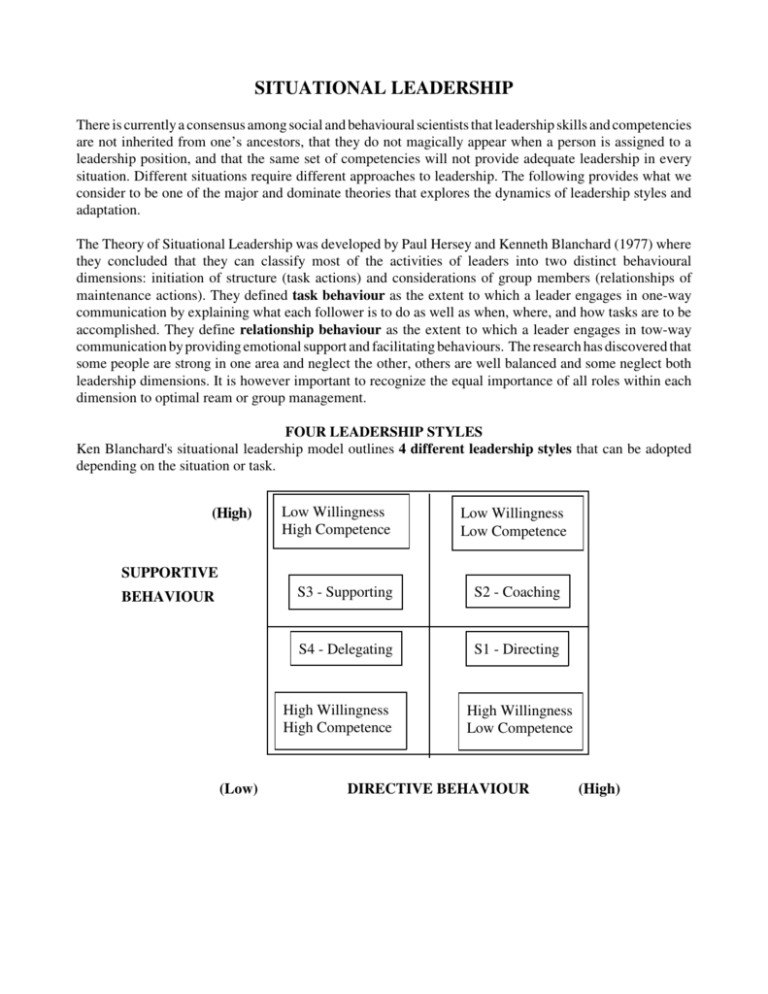

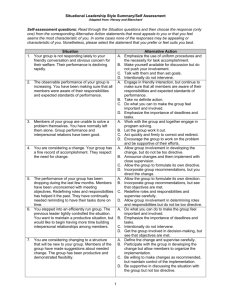

FOUR LEADERSHIP STYLES

Ken Blanchard's situational leadership model outlines 4 different leadership styles that can be adopted

depending on the situation or task.

(High)

Low Willingness

High Competence

Low Willingness

Low Competence

SUPPORTIVE

BEHAVIOUR

S3 - Supporting

S2 - Coaching

S4 - Delegating

S1 - Directing

High Willingness

High Competence

(Low)

High Willingness

Low Competence

DIRECTIVE BEHAVIOUR

(High)

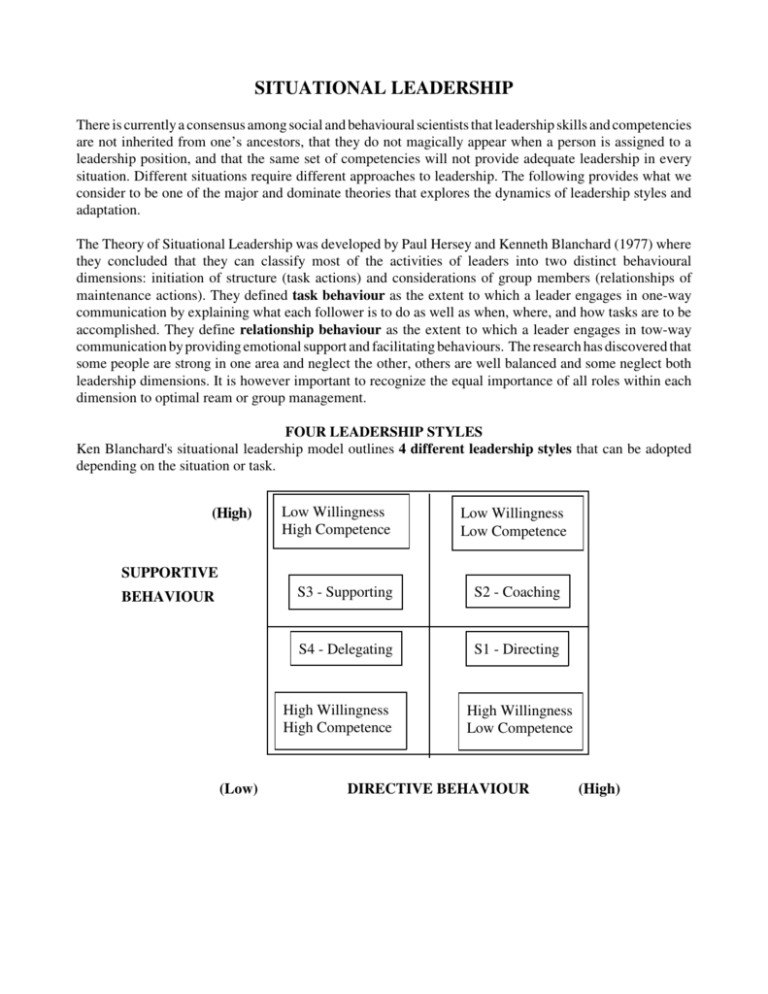

Maturity & Situational Leadership

Another important definition for understanding the situational leadership model is that of maturity. They

define maturity as the capacity to set high but attainable goals (achievement motivation), willingness and

ability to take responsibility, and the education or experience of the group members. Maturity is determined

only in relation to a specific task performed. On one task, a member may have high maturity; on another, low

maturity.

Mature

Immature

HIGH

MODERATE

MODERATE

LOW

M4

M3

M2

M1

Maturity of Follower(s)

Competence versus Commitment (Skill vs Will)

1. The leader assesses the development level of the “follower” with regard to completing a specific task. The

leader assesses the follower’s level of competence and commitment in that situation and correctly matches

their leadership style with the development level of the follower.

An effective leader is able to move fluidly between each leadership style, recognising that a follower will

have different development levels for different tasks.

(D1) Low Competence, Low Commitment – low skill level i.e. no training, understanding of how to complete

the task, previous experience and lacks motivation or confidence to complete the task.

(D2) Low Competence, High Commitment – has desire or incentive to complete task but low skill level.

(D3) High Competence, Low/Variable Commitment – can competently complete task but lacks confidence

or

perceives task as high risk

(D4) High Competence, High Commitment – experienced and motivated to complete task independently.

Leadership (S) Style

(S1) Directing – one-way communication where leader tells and shows follower what to do, and closely

supervises them doing it.

(S2) Coaching – two-way communication where leader directs what needs to be done, seeking ideas and

suggestions from the follower.

(S3) Supporting – leader focuses on motivation and confidence issues and leaves task decisions to follower.

(S4) Delegating – leader provides high-level direction only and further involvement and decision making is

controlled by follower.

Situational Leadership Continued

The essence of Hersey and Blanchard’s theory is that when group members have low maturity in terms of

accomplishing a specific task, the leader should engage in high-task and low-relationship behaviours (see

diagram on page one). When members are moderately mature, the leader moves to high-task and highrelationship behaviours and then to high-relationship and low-task behaviours. When group members are

highly mature in terms of accomplishing a specific task, then low-task and low-relationship behaviours are

needed.

Hersey and Blanchard refer to high-task-low-relationship leadership as directing (S1), because it is

characterized by one-way communication in which the leader defines the roles of the group members and tells

them how, when, and where to do various tasks. As the members’ experience and understanding of the task

goes up, so does their task maturity.

High-task-high-relationship leadership behaviour is referred to as coaching (S2), because while providing

clear direction as to role responsibilities, the leader also attempts, through two-way communication and

social-emotional support, to get the group members to psychologically buy into decisions that have to be

made. As group members’ commitment to the task increases, so does their maturity.

Low-task-high-relationship leadership behaviour is referred to as supporting (S3), because the leader and

group members share in decision making through two-way communication and considerable facilitating

behaviour from the leader, since the group members have the ability and knowledge to complete the task.

Finally, low-task-low-relationship behaviour is referred to as delegating (S4), because the leader allows

group members considerable autonomy in completing the task, since they are both willing and able to take

responsibility for directing their own task behaviour.

In closing, not all workers are ready and willing to step into the role as “leader.” They vary in their abilities

and in their willingness to do jobs. Looking at personnel records will tell you something about the worker’s

skill level. Taking time to talk with employees about their hopes, interests, and past experiences will help you

decide who to delegate to and/or what other strategy you may need to take.

Unfortunately, employees who are both able and willing are not always available. You can’t give the job to

the same worker all the time. This means you must make as effort to increase the willingness and skills of

your workers. If you want to use the full capabilities of people, job enlargement or job enrichment should be

a concern for all managers. It will help employee morale and make for more able workers.

You should also try to increase workers’ willingness to accept task. One good way is to find out what they

like to do, and what they are good at - then delegate that. Another way is to let them help set goals. Having

ownership of goals will increase their willingness to work towards reaching the goal.

Copyright © 2004, Peak Experiences - The Learning Company, All Rights Reserved