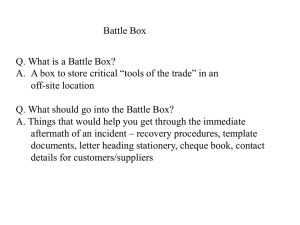

Guide to Business Continuity Management

advertisement