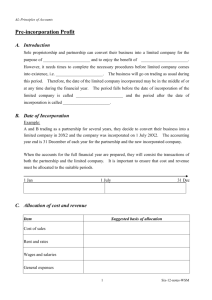

Pre-Incorporation Transactions - University of Manitoba Faculty

advertisement