Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Contents

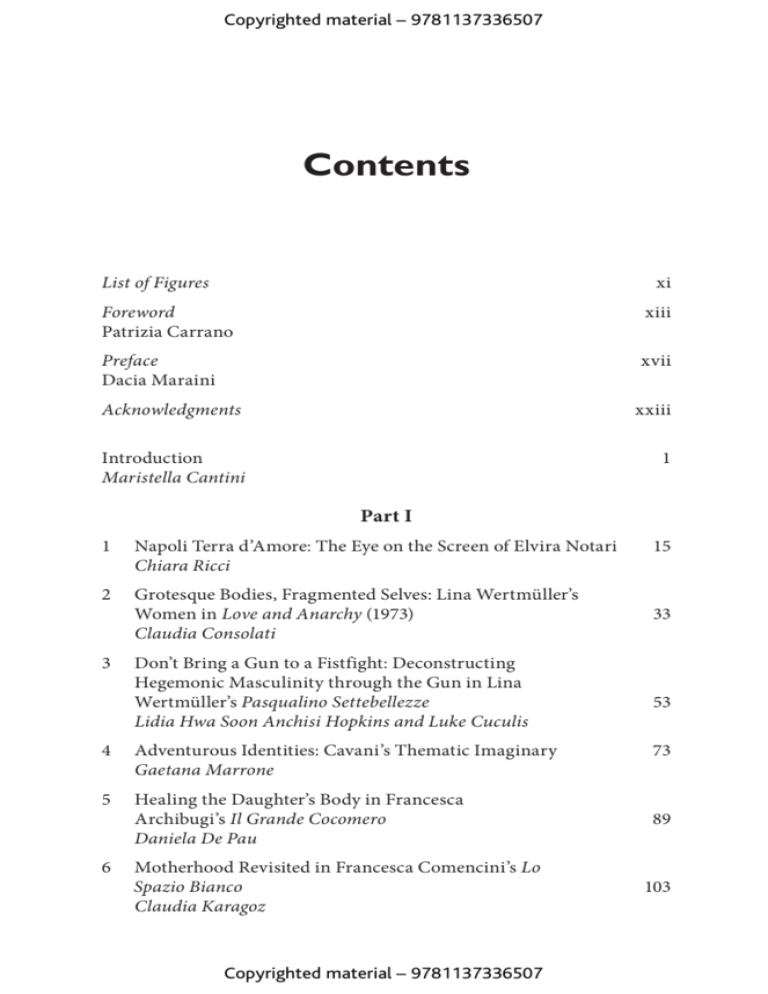

List of Figures

xi

Foreword

Patrizia Carrano

xiii

Preface

Dacia Maraini

xvii

Acknowledgments

xxiii

Introduction

Maristella Cantini

1

Part I

1

Napoli Terra d’Amore: The Eye on the Screen of Elvira Notari

Chiara Ricci

2

Grotesque Bodies, Fragmented Selves: Lina Wertmüller’s

Women in Love and Anarchy (1973)

Claudia Consolati

3

Don’t Bring a Gun to a Fistfight: Deconstructing

Hegemonic Masculinity through the Gun in Lina

Wertmüller’s Pasqualino Settebellezze

Lidia Hwa Soon Anchisi Hopkins and Luke Cuculis

4

Adventurous Identities: Cavani’s Thematic Imaginary

Gaetana Marrone

5

Healing the Daughter’s Body in Francesca

Archibugi’s Il Grande Cocomero

Daniela De Pau

6

Motherhood Revisited in Francesca Comencini’s Lo

Spazio Bianco

Claudia Karagoz

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

15

33

53

73

89

103

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

x

CONTENTS

7

8

9

10

11

Women in the Deserted City: Urban Space in Marina

Spada’s Cinema

Laura Di Bianco

121

Envisioning Our Mother’s Face: Reading Alina Marazzi’s

Un’ora sola ti vorrei and Vogliamo anche le rose

Cristina Gamberi

149

Alina Marazzi’s Women: A Director in Search of

Herself through a Female Genealogy

Fabiana Cecchini

173

Angela/o and the Gender Disruption of Masculine

Society in Purple Sea

Anita Virga

195

Ilaria Borrelli: Cinema and Postfeminism

Maristella Cantini

209

Part II

12

Skype Interview with Alina Marazzi (June 2012)

Cristina Gamberi

231

13

Interview with Marina Spada (Milan, June 2012)

Laura Di Bianco

237

14

Interview with Alice Rohrwacher (Rome, June 2012)

Laura Di Bianco

247

15

Interview with Paola Randi (Rome, June 2012)

Laura Di Bianco

253

16

Interview with Costanza Quatriglio (July 2012)

Giovanna Summerfield

263

Notes on Contributors

273

Index

279

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

ITALIAN WOMEN FILMMAKERS AND THE GENDERED SCREEN

Copyright © Maristella Cantini, 2013.

All rights reserved.

First published in 2013 by

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN®

in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC,

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world,

this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited,

registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills,

Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS.

Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies

and has companies and representatives throughout the world.

Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States,

the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.

ISBN: 978–1–137–33650–7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the

Library of Congress.

A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.

Design by Newgen Knowledge Works (P) Ltd., Chennai, India.

First edition: December 2013

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Introduction

Maristella Cantini

Ma la ritorna poi fiacca e smarrita

oscura tema, che con lei si mesce,

che la sua luce tosto fia sparita.

—Gaspara Stampa

T

he idea for this book began to develop a long time ago. After much

consideration, I discussed the project with cinema scholars and several colleagues who work primarily on Italian film studies. The response

produced by our conversations was unmistakably similar: “Are you sure

you have enough material for a book? Besides Wertmüller and Cavani,

who else is there to fill up a book of essays about women filmmakers?”

These questions left me with the urge to respond. Despite the fact that

those I consulted were knowledgeable and possessed considerable expertise, they were unaware of the wealth of material available to explore.

Clearly, a widespread lack of visibility of women filmmakers exists, even

to experts in the field. Thus, development of such a volume of essays

became all the more necessary in order to promote the criticism I hope

it will encourage.

As a matter of fact, a profusion of material about Italian cinema does

exist. Specifically, topics such as Neorealism, women’s representation,

postwar cinema, fascism, new millennium cinema, and new contemporary trends are all profusely explored and discussed by Italian film scholars both in English and in Italian. In contrast, there seems to be an absence

of any serious, committed critique focusing on women filmmakers.

Feminist film criticism in Italy lacks energy and visibility, and the topic

of women directors’ authorship is, indeed, still marginalized. This dearth

of critical examination exists despite the proliferation of associations and

groups that intend to promote women’s art, literature, and cinema, such

as Associazione Ipazia, Laboratorio Immagine, Associazione Maude, and

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

2

MARISTELLA CANTINI

Associazione Ada, and the many festivals that promote women’s cultural

production in various fields. A persistent halo of isolation and silence

affects especially Italian cinema authored by women when it comes to academic debate, histories of Italian cinema, and film criticism collections.

No collections of essays, very few monographic works, and up until a few

years ago, very few online articles and critical contributions exist. In terms

of academic critique then, a deep void engulfs women filmmakers and

affects their work and professional distinctness.

As the editor of this project, my intention is to bring visibility to Italian

women directors, not as a niche topic, but as a central theme of Italian

cinema. Cinema authored by women has been ignored, if not “surgically

removed,” by traditional mainstream criticism. I would like, therefore,

to redress the established practice of critical analysis and invite a fresh,

transparent debate about the work of Italian women directors. This book

aims to reposition the idea of Italian cinema, which, today, remains a synonym for male-authored cinema, and intentionally challenges the existing body of work written by well-known critics that unmistakably favors

the work of male directors over that of their female counterparts.

I will mention one seminal academic work—Italian Cinema from

Neorealism to the Present by Peter Bondanella—that has served as an

important guide for me in recent years. As well as being adopted as a textbook in several courses of Italian cinema, including those that I had the

pleasure to attend, it has been a guide in terms of critical discourse. A

vast amount of feminist criticism by scholars ranging from Laura Mulvey,

Annette Kuhn, Ann Kaplan, and Jeanine Basinger, to Angela McRobbie

and Janet McCabe, and pro-postfeminist theorists such as Stephanie

Genz, Hilary Radner, and Yvonne Tasker, to name but a few, inspired

me to examine Italian film studies critical texts from a different angle. In

the introduction to Feminism and Film (2000), Kaplan explains that “film

is an important object—as literature was before it—that with feminist perspective may help to change entrenched male stances towards women, and

feminist film study may even change attitudes towards women” (2).

While Bondanella’s book is indeed an accurate work of refined criticism, it focuses exclusively on male directors’ work, and most importantly,

it is written from a male point of view. The more-than-five-hundred-page

book concisely presents Liliana Cavani and Lina Wertmüller among an

interminable list of male filmmakers, who are deeply explored. There is

no mention of any other female director. The first part of the book, moreover, offers an initial overview of silent cinema, and yet includes no trace

of Elvira Notari’s work.1 The Italian filmmaker directed a surprising

number of movies and documentaries, and enjoyed a full life dedicated

to filmmaking, which has only recently been critically reevaluated by

women scholars and writers such as Giuliana Bruno and Chiara Ricci.

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

INTRODUCTION

3

Furthermore, many comprehensive histories of Italian cinema,

published in Italian and English, portray Italian male-authored cinema

in a noble light, completely removing a whole category of films, namely

salacious comedies—by directors such as Nando Cicero—that flooded

Italian cinemas in the 1970s and proved popular with male audiences.

The “cinepanettone,” so called because the movies were often released

at Christmas time, is another “niche” category of popular comedy films,

quite successfully mastered by director Carlo Vanzina. The derogatory

treatment of women by these filmmakers and in these productions has

not, to my knowledge, been analyzed or debated, despite the considerable number of publications authored by male critics. Women filmmakers in Italy in the 1970s approached the camera more confidently and

used it for political activism, to promote crucial innovations in terms

of social and ethical revolution, debating on abortion, divorce, and the

fair regulation of work outside the family. Yet, all the while, male directors inundated Italian cinema with erotic, commercial comedies featuring young, naked female protagonists, insistently ignoring the women’s

movement, thereby nullifying its demands. Moreover, this kind of cinema gained its popularity through featuring idealized female characters

both, sexually available and inviting, ready to please men and tickle

their erotic fantasies, clearly reinstating women’s roles in the sphere of

the male-controlled realm.2

The Anglo-American debate in film criticism has dominated the international scene since the early 1970s. Coinciding with the rise of the feminist

voice, a number of significant works were published and these triggered a

crucial debate on women’s representation, a debate that continues to this

day with postfeminist, postmodern, and, to keep up with the terminology jam, poststructuralist inquiry. I refer to Claire Johnston, who in 1975

published research on Dorothy Arzner, an important step particularly, as

E. Ann Kaplan notes, “to list the basic situations of the female protagonists

in Arzner’ s films, showing the women’s efforts to transgress the male order

and assert themselves as subjects.”3 Laura Mulvey wrote an essay titled

“Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” which became a groundbreaking

intervention for feminist film criticism. Kaplan in 1978 edited a volume

on Women in Film Noir. I also refer to the blossoming of magazines on

film studies such as Screen in England, Cahiers du Cinema in France, and

Frauen und Film in Germany, which was first published in 1974.4 In Italy,

Cinzia Bellumori published Le donne del cinema contro questo cinema in

1972, a hundred-page report detailing women’s conditions in the Italian

film industry. Bellumori’s report reveals a dysfunctional environment

where the majority of women employed in the sector were chronically

unable to move forward, penalized by male chauvinism and by the impossible task of juggling motherhood and pressing job demands (70–84). She

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

4

MARISTELLA CANTINI

details their stories in interviews with actresses, screenwriters, secretaries,

costume designers, and assistants included in the book. Patrizia Carrano’s

book Malafemmina, published in 1977, served as an explosive denunciation of Italian cinema both in terms of commercial industry and as a

cultural production system. Carrano’s book was followed, in subsequent

years, only by isolated articles and debates, without any united front of

academics or critics active in this field.

Despite the great number of prominent female intellectuals, activists,

and politically engaged figures in Italy, the legacy of feminist criticism

has made a considerably less-durable (and incisive) contribution to the

debate. Since the 1970s that legacy has suffered an increasing degree of

isolation and fragmentation in terms of feminist film criticism. Even if the

production of feminist filmmakers in those years of activism and radical

change was surprisingly fruitful, the resistance didn’t last long enough to

create sufficient visibility for women directors. As Aine O’Healy writes,

“In the more conservative atmosphere that prevails in Italy in the mid1990s, feminist activism no longer has the momentum it once had, and

many gains have been threatened or retracted over time.”5 In the 1970s

and 1980s, numerous women directors were activists who decided to step

into the forbidden area and occupy the cinematic arena. Nevertheless,

there was no established, proactive debate on feminism and films to maintain and even force a long-lasting visibility on women’s authored cinema.

Subsequently, none of those names, apart from Lina Wertmüller and,

later, Liliana Cavani, entered in cinema’s manuals or studies. Giuliana

Bruno and Maria Nadotti’s writings on the modality of feminist dynamics in Italy strike me as particularly incisive. To use their words, the path

pursued by American feminism, that of acquiring the status of a formal

discipline, a field of “scholarship” or a path that has generated “feminist

film theory” has no parallel in Italy, in part due to the long-term lack of

academic institutionalization of the subject (Bruno and Nadotti 1988: 9).

This is an important facet of the theoretical approach to feminist film

studies. The absence of an established culture of debate does not mean

that there are no feminist intellectuals and competent critics; it means

that they operate in a very fragmented ideological and cultural setting.

I do not go so far as to imagine that this book will accomplish the ambitious task of filling the void that exists in Italian film criticism. The intent

is to stimulate criticism of and attention toward Italian women filmmakers and their position both in Italy and on a wider international platform.

I would like to continue the debate that Dacia Maraini, author of the preface in this volume, and Patrizia Carrano, author of the foreword, started

years ago, ignored by mainstream cinema, which is now, more than ever,

controlled by a strong androcentric pseudoculture. I believe that Italian

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

INTRODUCTION

5

cinema, as a medium reflecting the culture of our country, is relatively

unchanged, in terms of patriarchal conformation, from forty years ago.

In Ilaria Borrelli’s novels, in particular Domani si Gira (Tomorrow We

Shoot), which is strictly autobiographical, many details seem to actually coincide with Carrano’s invective. My questions are: Why has it not

changed even slightly? Why are women still struggling to find their own

space in this profession, free from male precepts and guidance? How can

such a sexist stronghold be overthrown? I asked Ilaria Borrelli the latter

question, and her immediate reply was: “We should have more women in

charge and in key positions.”6

No shortage of talented Italian female directors exists to uphold as

mentors, and alleged histories of Italian cinema continue to proliferate

through the systematic neglect of women’s documentaries and movies.

Women filmmakers’ “transparence-absence,” to use Patrizia Carrano’s

expression,7 is not a matter of cinematic ability or artistic maturity; rather,

it is the result of a deliberate act of marginalization from male-authored

cinema. It is the same kind of marginalization that Italian intellectuals

such as Dacia Maraini, Anna Bravo, Lilli Gruber, Daniela Danna, Chiara

Valentini, and many others have radically denounced in literature, journalism, art, politics, science, academic research, and a long list of primary

areas of knowledge. Cinema, one of those areas, is greatly affected by this

practice, and the contribution of women is greatly overshadowed by male

predominance in the field. In her book Mujeres de Cine. 360º alrededor de

la Cámara (2011), Maria Caballero Wangüemert states that exclusion of

women from filmmaking is a phenomenon resembling the treatment of a

minority group, if we consider that out of twenty thousand directors, only

3 percent are women, with Spain reaching 13 percent (21).8 No current

data are available for Italy: no statistics and no official records regarding

the work of women filmmakers. This lack of information provokes many

questions, including: How many women filmmakers are working in the

industry? How many movies are produced every year by female filmmakers? How are those films produced and distributed? How do they receive

funding? Who is eligible for funding? Why are many of the female directors recognized and awarded by the most ambitious festivals, only then to

disappear in a cloud of oblivion? Who does evaluate the artistic content of

movies authored by women and how many of those “experts” are women?

In other words, who is dictating and imposing a canonical, traditional

criticism that establishes who can enter a History of Italian Cinema and

who can be grouped in a general footnote (and be lucky to be there)?

Italian female directors are artists in a broader sense.9 Some are writers, musicians, painters, photographers, poets, or documentary-makers.

Many are scriptwriters, actresses, playwrights, and producers. The primary

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

6

MARISTELLA CANTINI

intention of this collection is to show how rich, intriguing, and “global”

their films are and how engaging the critical discussion they generate can

be. Their movies focus on women—although not exclusively—from different angles and quite distinctively from the way in which they are featured in male-authored cinema. Italian women filmmakers do not focus

on the divas, sex-symbols, or physically perfect icons that male fantasy

has produced in postwar cinema. In contrast, the directors included in

this book portray female characters that develop a stronger sense of self

within the cinematic narrative of each individual film by engaging in

more complex relations with other women, exploring a vast array of situations and viewpoints. These threads weave together to form the fabric of

women’s interactions that empower the characters and reposit the female

discourse at the center of the movie. Italian female directors observe their

environment, the space they inhabit, their family ties, their most important relationships, and their many roles. Social issues are always present

in these artists’ work, and the personal is still political, even in the case of

light-hearted comedies.

The intent to show the persistent engagement of female directors with

social topics as well as more personal ones determined the selection of

essays collected in this volume. In addition, universal themes such as

immigration, spatial or emotional displacement, and marginalization,

force the boundaries of national circuits, moving toward more global

issues that are specific to women. Those issues include motherhood, prostitution, domestic and cultural violence, lesbianism, work-related abuse,

and gender discrimination. I brought together voices that have been both

constitutive and representative of Italian cinema since its inception, in

order to give a sample of their powerful and subversive efficacy.

Italian Women Filmmakers and the Gendered Screen is divided into

two parts: the first section contains essays on women filmmakers, starting from Elvira Notari (1875–1946), who was the first Italian woman filmmaker and scriptwriter and who produced a great number of exceptional

films and documentaries. Next come two essays on Lina Wertmüller.

Claudia Consolati discusses Love and Anarchy (1973), which still generates polemics due to its antifeminist perception of female characters.

Lidia Hwa Soon Anchisi Hopkins and Luke Cuculis, with “Don’t Bring

a Gun to a Fist Fight: Deconstructing Hegemonic Masculinity through

Gun in Lina Wertmüller’s Pasqualino Settebellezze,” engage a reflection on masculinity impersonated by the male protagonist Pasqualino

Settebellezze. A concentration camp survivor, Settebellezze entraps

the spectator between the comical and grotesque urge to live over the

brutal sacrifice of his friend. Gaetana Marrone, a renowned scholar of

Liliana Cavani and author of her more recent biography, presents an

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

INTRODUCTION

7

article on Liliana Cavani’s Thematic Imaginary. Here the contributor

discusses the ability of the director to depict both spirituality and carnality on screen, through the figures of San Francesco (St. Francis),

Milarepa, and in Cavani’s last movie Le Clarisse, nuns of the Santa Clara’s

order. “Healing the Daughter’s Body in Francesca Archibugi’s Il Grande

Cocomero” opens a discussion on a mother-daughter relationship at different levels. It follows Claudia Karagoz’s analysis of the movie Lo Spazio

Bianco by director Francesca Comencini. Karagoz’s inquiry concentrates

on nontraditional maternity as chosen by the protagonist Maria and her

newborn daughter Irene. In her analysis, Karagoz also brings to the surface the sense of physical displacement of Maria’s character, both in terms

of space and emotional perception. Laura Di Bianco’s chapter “Women in

the Deserted City: Urban Space in Marina Spada’s Cinema” develops the

theme of urban environment as an element that cinematically contributes to frame the female protagonist from a more intimate perspective.

The role of the mother-daughter returns in terms of regaining possession of a female deeper self. The theme prevails in Alina Marazzi’s film

documentary Un’ora Sola ti Vorrei and Vogliamo anche le Rose as presented by Cristina Gamberi in her essay “Envisioning Our Mother’s Face.

Reading Alina Marazzi’s Un’ora sola ti vorrei and Vogliamo anche le rose.”

Gamberi deeply explores Marazzi’s attempt to “quilt” the memory of her

mother through a recuperation of images, sounds, and family videos, in

order to rehabilitate not only the mother as a component of her own identity, but as the woman in particular.

The second part of the book consists of recent and previously unpublished interviews. Some are with filmmakers discussed in the essays to

offer the critical interpretation and direct voice of the filmmakers themselves. Other interviews have been included to give voice to as many

women filmmakers as possible, in order to display their antinomies and

mirroring similarities. Marina Spada and Alina Marazzi answer the

authors who discuss their cinema, offering the possibility of other interpretations, while Costanza Quatriglio, Paola Randi, and Alice Rohrwacher

complement the studies of their work with their own opinions. It was a

very difficult choice to decide what material and author to select and how

to orchestrate a multilayered idea of their work and their personalities.

All proved engaging and incredibly inspiring.

Because, as noted earlier, I was unable to find similar material on

Italian cinema that reflected women’s work from a different perspective,

I have taken inspiration from collections edited by women scholars in

or about other cultural contexts such as: Women Filmmakers Refocusing,

edited by Jaqueline Levitin, Judith Plessis, and Valerie Raul; Reclaiming

the Archive, edited by Vicky Callahan; and collections on single women

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

8

MARISTELLA CANTINI

directors such as The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow. Hollywood Transgressor,

edited by Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond; Jane Campion. Cinema,

Nation, Identity, edited by Hilary Radner, Alistair Fox, and Irène Bessière;

Canadian Women Filmmakers: Re-imaging Authorships, Nationality, and

Gender; and Canadian Women Filmakers. The Gendered Screen,10 both

edited by Brenda Austin-Smith and George Melnyk. These works, among

many other groundbreaking studies, gave me ideas on how much freedom I had in editing this book. Many collections simply reject the path

of traditional analysis, even from a graphical point of view. They may

articulate their discourse through puzzling visual forms and stylistic creativity. However, my main purpose is to highlight the polyhedral content

of the filmmakers’ movies addressed in this collection, and the polemical

criticism all of them can engender.

The attempt to bring together critics from several areas of academia

seemed to pose uniformity as a central issue for some of our valued

reviewers. Uniformity is not my priority here. On the contrary, I aimed to

produce a collaborative and pioneering work (nothing at this time exists

for us to measure with) that offers unlimited possibilities for criticism,

changing the perception of Italian cinema from a monolithic, solid subject to a more fluid, prismatic, and global one. I privilege an idea of continuity instead of new cinema, because I believe in the much that has been

done and written and in the huge that is still undone.

Notes

1. While I have only mentioned this book, which I consider a great but partial

analysis, I can also add another classic by Gian Piero Brunetta, The History

of Italian Cinema. A Guide to Italian Film from its Origins to the TwentyFirst Century, translated by Jeremy Parzen (Princeton; Oxford: Princeton

University Press, 2003). The publications of the last ten years also follow

the same patterns, redefining and reinforcing the exclusion of women.

Some of these works, to mitigate the bias, may include a sporadic chapter on

one woman director but the essential core of such studies unavoidably focuses

on male cinema. Occasionally, some texts cite or acknowledge women directors’ names without undertaking any real analysis of their works. See, for

instance, Il Cinema Italiano del Terzo Millennio edited by Franco Montini

and published in 2002. In this book only Nina Di Majo is included of seven

directors interviewed. It is crucial to note that there are no comprehensive histories of Italian cinema written by women as of yet. Scholars such as Marcia

Landy, Marga Cottino-Jones, Flavia Brizio-Skov, and many other female film

scholars, did not attempt to write absolute histories of Italian cinema, but

instead focused their attention on quite distinctive parts or aspects of it, and

women’s issues are steadily at the center of the debate in the works of these

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

INTRODUCTION

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

9

authors. There are no histories of Italian cinema written by women scholars,

which is another big void in our body of criticism.

I refer here to movies such as L’insegnante (The Teacher) directed by Nando

Cicero, and La portiera nuda (The Naked Woman Porter, 1976) directed by

Luigi Cozzi. The list of titles for these comedies is endless and spans through

the 1980s with a rich, and quite pathetic, repertoire. Many of these movies also present scenes where women touch or undress other women, in a

vast range of male voyeuristic curiosity for women same-sex relationships,

with the morbid intent to visually control women’s bodies and sexuality.

Accurate feminist research about this aspect of Italian cinema is needed. In

Malafemmina, Patrizia Carrano speaks out against the perverted dynamics

“behind the scenes” in Italian cinema: the treatment experienced by women

of all ages, the objectification of their bodies, and the absence of a whole

generation of artists with the ability to interpret roles beyond the “young

and sexy” in a career-limiting sentence inflicted upon many of Italy’s best

actresses and women professionals (129–190). See the articles of Monica

Repetto, “Ciao Mamma. Ovvero Porno Soffice ed Erotismo da Ridere,” and

Angela Prudenzi, “Il Vizio di Famiglia. Ovvero Gruppo di Famiglia dal

Buco della Serratura,” in Lino Miccicchè, ed., Il Cinema del Riflusso. Film,

Cineasti Italiani degli anni ’70 (Venezia: Marsilio, 1997), 317–333 and 334–

340, respectively. These articles present the trash comedy trend of the 1970s

and 1980s with a condescending tone toward the male authors, but without

inquiring too deeply into how these movies trivialize women. Please note

that the book does not discuss women documentary makers or women filmmakers of those years.

http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/jc12–13folder/britfemtheory.

html (accessed March 15, 2013).

For an extensive reflection, see Ann Kaplan, Feminism and Film (Oxford,

UK; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Aine O’Healy, “Italian Feminism and Women’s Filmmaking: Intersections 1975–1995,” http://tell.fll.purdue.edu/RLA-Archive/1995/Italianhtml/O’Healy,Aine.htm (accessed October 25, 2012). The author traces a

vivid situation on the activity of cinema in Italy in the period 1975–1995.

Nevertheless, of these important filmmakers such as Lina Mangiacapre,

Wilma Labate, Emanuela Piovano, and many others, there is no trace in conventional academic studies.

The interview with the director via Skype on June 5, 2012, was recorded on

tape and Audacity. Amusingly, I read an article in Glamour magazine (June

2010, p. 64) where the title screams: “Hey Hollywood: DO Put More Women

in Charge.” Journalist Laurie Sandell speaks to Jane Fleming, the president

of WIF (Women in Film), a not-for-profit organization that aims to improve

women’s leadership in Hollywood and lobbies about the situation of women

in mainstream cinema. According to the journalist, there are a few “glass

ceilings left in the USA: the oval office, NFL, and cinema.” The American

numbers, according to Sandell, are quite clear: in 2009, out of 250 box-office

hits, only 7 percent were “helmed by women.”

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

10

MARISTELLA CANTINI

7. Patrizia Carrano used this term in an exchange of emails with the editor.

8. In her book Mujeres detrás de la Cámara. Entrevistas con Cineastas Españolas

1990–2004 (Madrid: Ocho y Medio, 2005), María Camí-Vela writes that in

Spain, during the last decade, the number of women filmmakers reached 20

percent of the total directors. She also lists a number of components for this

professional inferiority: a lack of self-confidence due to a long-term condition of exclusion from an active role in this field, as well as a time frame:

men start much earlier than women to direct movies. Women, moreover,

manifest the need to tell their own stories instead of interpreting others’, as

Iciar Bollain confirms in her interview (51–65). Please note that statistics can

be approximate and confusing, even for Spain. Both Caballero-Wangüemert

and Camí-Vela are not really clear about actual numbers.

9. This is a common feature in women filmmakers worldwide, and I believe it

is linked to their personal and professional paths.

10. Please note that the title of this book has been a fortuitous rework of several

possible titles, between the editor and the editorial board of Palgrave. I liked

the outcome: it is very close to the book of George Melnyk and Brenda Austin

Smith, The Gendered Screen:Canadian Women Filmmakers (Waterloo, ON:

Wilfried University Press, 2010). This is one of the first books that inspired

my work.

Bibliography

Basinger, Janine. How Hollywood Spoke to Women. New York: Alfred A. Knoff,

1993.

Bellumori, Cinzia, a cura di. “Le Donne del Cinema Contro Questo Cinema.” In

Bianco e Nero, 1–2 (1972): 2–112. Roma: Società Gestioni Editoriali.

Blaetz, Robin, ed. Women’s Experimental Cinema. Critical Frameworks. Durham;

London: Duke University Press, 2007.

Bondanella, Peter. Italian Cinema. From Neorealism to the Present. New York;

London: Continuum, 2001.

Brunetta, Gian Piero. The History of Italian Cinema. A Guide to Italian Film

from its Origins to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton

University Press, 2003.

Bruno, Giuliana, and Maria Nadotti. Off Screen: Women and Film in Italy.

London; New York: 1988.

Caballero-Wangüemert, Maria. Mujeres de Cine. 360º Alrededor de la Cámara.

Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 2011.

Camí-Vela, Maria. Mujeres detras de la Cámara: Entrevistas con Cineastas

Españolas 1990–2004. Madrid: Ocho y Medio, 2005.

Callahan, Vicky, ed. Reclaiming the Archive: Feminism and Film History. Detroit,

MI: Wayne State University Press, 2010.

Carrano, Patrizia. Malafemmina. Rimini; Firenze: Guaraldi Editore, 1977.

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

INTRODUCTION

11

Cottino-Jones, Marga. Women, Desire, and Power in Italian Cinema. New York;

Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Foster, Audrey, Gwndolyn Katrien Jacobs, and Amy L. Unterburger. Women

Filmmakers & Their Films. Detroit: St. James Press, 1998.

Hurd, Mary G. Women Directors and Their Films. Westport, CT; London:

Praeger, 2007.

Isola, Simone, ed. Cinegomorra. Luci e Ombre sul Nuovo Cinema Italiano. Roma:

Sovera Edizioni, 2010.

Jermy, Deborah, and Sean Redmond. The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow. Hollywood

Transgressor. London; New York: Wallflower Press, 2003.

Kaplan, E. Ann. http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/jc12–13folder/

britfemtheory.html.

———. Feminism and Film. Oxford, UK; New York: Oxford University Press,

2000.

Koenig Quart, Barbara. Women Directors. The Emergence of a New Cinema. New

York; Westport, CT; London: Praeger, 1988.

Landy, Marcia. Stardom Italian Style: Screen Performance and Personality in

Italian Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Levitin, Jacqueline, Judith Plessis, and Valerie Raoul. Women Filmmakers.

Refocusing. New York; London: Routledge, 2003.

McRobbie, Angela. The Aftermath of Feminism. Gender, Culture and Social

Change. London, UK: Sage Publications, 2009.

Melnyk, George, and Brenda Austin-Smith. The Gendered Screen: Canadian

Women Filmmakers. Waterloo, ON: Wilfried University Press, 2010.

Montini, Franco, ed. Il Cinema Italiano del Terzo Millennio. I Protagonosti della

Rinascita. Torino: Lindau, 2011.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In Visual and Other

Pleasures, edited by Laura Mulvey, 14–27. Basingstoke, UK; New York:

Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

O’ Healy, Aine. “Italian Feminism and Women’s Filmmaking: Intersections 1975–1995,” http://tell.fll.purdue.edu/RLA-Archive/1995/Italianhtml/O’Healy,Aine.htm (accessed October 25, 2012).

Tasker, Yvonne. “Women Filmmakers, Contemporary Authorship, and Feminist

Film Studies.” In Reclaiming the Archive: Feminism and Film History, edited by

Vicky Callahan, 213–229. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2010.

Zagarrio, Vito. La Meglio Gioventù. Nuovo Cinema Italiano. Venezia: Marsilio,

2006.

———. Il Cinema della Transizione: Scenari Italiani degli anni Novanta. Venezia:

Marsilio, 2000.

Valentini, Chiara. O I figli o il Lavoro. Milano: Feltrinelli, 2012.

Zajczyk, Francesca. La Resistibile Ascesa delle Donne in Italia. Milano: Il

Saggiatore, 2007.

Wang, Lingzhen. Chinese Women Cinema: Transnational Contexts. New York:

Columbia University Press, 2011.

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Index

Note: Locators followed by ‘n’ refer to notes.

81/2 , 35

Abraham, Fred Murray, 210

Ahmed, Sara, 149

Akhmatova, Anna, 123, 243

Althusser, Louis, 64, 137

Amelie, 216, 226n11

Amore e violenza (Melandri), 97

Anchisi Hopkins, Lidia Hwa Soon, 6,

53–67, 273

Antonioni, Michelangelo, 121, 131–2,

138–9, 241, 244

Aprà, Adriano, 152

Archibugi, Francesca

biography, 98

filmography, 100–101

Il grande cocomero: family

dynamics in, 92; healing and,

96–8; illness and, 93–6; plot,

92–3

Mignon è partita, 92, 98

Verso Sera, 92

Argento, Dario, 175

Arzner, Dorothy, 3

Austin, J. L., 64–5

Austin-Smith, Brenda, 8

automediality, 181

“autrici interrotte,” 129, 145n13

avventura ancora attuale, 76

Bahktin, Mikhail, 43

Baldry, Anna Costanza, 91

Balestrini, Nanni, 123, 243

Barthes, Roland, 38, 139

Basilico, Gabriele, 131, 133–5, 237,

239–41, 243

Basinger, Jeanine, 2

Battiato, Franco, 174

Baudelaire, 122, 136

Bellassai, Sandro, 55–8, 69n9

Bellumori, Cinzia, 3

Benini, Stefania, 212

Bertolucci, Giuseppe, 178

Bettelheim, Bruno, 68n3

Bhabha, Homi, 197

Bondanella, Peter, 2, 48n8

“Border Traffic” (O’Healy), 137

Borrelli, Ilaria

biography, 224–5

Come le Formiche, 220–2

Domani si Gira, 5, 211

films, 218–24

Il piu bel Giorno della mia Vita, 222

Luccatmi, 211

Mariti in Affitto, 218–20, 222

novels, 5, 210–12

overview, 209

postfeminism, 212–18

Scosse, 210

Talking to the Trees, 222–4

Tanto Rumore per Tullia, 211–12

Bowlby, Rachel, 143

Brabon, Benjamin, 213–14

Bridget Jones’ Diary, 214–16

Brundson, Charlotte, 215–16

Bruno, Giuliana, 2, 4, 16–17, 19, 23–4

Butler, Judith, 54, 56, 63–7, 69n8, 197,

199, 207n6

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

280

INDEX

Cannes Film Festival, 263

Cannistraro, Philip, 69n11

Canova, Gianni, 175–6

Cantini, Maristella, 1–8, 209–25, 273

Carmosino, Christian, 264

Carrano, Patrizia, 4–5, 9n2, 10n7,

225n1, 273–4

Cattaneo, Menotti, 19

Cavani, Liliana

early films, 73–4

filmography, 87–8

Francesco di Assisi, 73–7, 82, 84

Galileo, 77–8

I cannibali, 78–9

Le clarisse, 83–4

L’ospite, 79–80

Milarepa, 80–2

operas, 88

scholarship on, 1–2, 4, 6–7

secular view, 77

Seventh Circle, 83

Thematic Imaginary, 73–85

themes in works of, 82–5

Cecchini, Fabiana, 173–87, 274

Chick Flicks, 216–18, 222, 224, 226n11

Chinn, Sarah, 64

Cicero, Nando, 3, 9n2

Cicioni, Mirna, 178

cinèma vérité, 152, 232

cinepanettone, 3

“citational grafting,” 64–5

Color Purple, The, 216

Comencini, Francesca

biography, 115

filmography, 118–19

Lo spazio bianco: characters, 107–9;

inclination in, 114–15; mothers

and, 104; plot, 104; portrayal of

Naples, 108–11; staging spaces,

111–15; themes, 104–6, 110–11;

translation from book to film,

106–7; women’s bodies and, 104–5

SNOQ and, 103

Comenici, Luigi, 115

“concrete brotherhood,” 85

Connell, R. W., 55

Consolati, Claudia, 6, 33–46, 274

Conte, Paolo, 174

Criminal Woman (Lombroso), 203

Cuculis, Luke, 6, 53–67, 274

de Certeau, Michel, 125

de Lauretis, Teresa, 34, 37, 45, 48n7,

50n41, 150

De Pau, Daniela, 89–99, 275

Derrida, Jacques, 64–5

Di Bianco, Laura, 7, 121–44, 237–61,

275

Diaconescu-Blumenfeld, Rodica, 36,

40, 43

Diary of Sex and Politics, 164

Discipline and Punish (Foucault), 203

Doane, Mary Ann, 34, 44–5

Domani si Gira (Borrelli), 5, 209, 211

drag, 54, 63, 65–6, 69n8, 207n6

Dünne, Jörge, 181

Farinotti, Luisella, 159

Fellini, Federico, 29n6, 35–6, 40

femicide, 90

Ferris, Suzanne, 216

Festival of Bratislava, 263

Festival of Cuenca, 263

Festival of Montreal, 225

Festival of Pusan, 263

Festival of Turin, 263

Finocchiaro, Angela, 115n2

flânerie, 122, 125–7, 136, 138, 143

Forgacs, David, 122

Foucault, Michel, 76, 203, 207n8

found footage, 150–1, 153–4, 166, 176,

178–9, 182, 186, 231–3

Fraioli, Ilaria, 159, 161, 165, 167, 181,

183, 233

Franchi, Paolo, 173

Freud, Sigmund, 37–8

Fried Green Tomatoes, 216

Gamberi, Cristina, 7, 149–67, 178–9,

186, 231–5, 275–6

Garrone, Matteo, 173, 176, 257

Gay, Piergiorgio, 173, 178

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

INDEX 281

gaze

Cavani and, 85n5

Come l’ombra and, 129, 131, 137–8

documentaries and, 232, 234,

240–1, 244–5

female, 138, 183, 252, 260, 268

Kaplan on, 42

La Notte and, 131

Lo spazio bianco and, 113–14

Love and Anarchy and, 34–7, 41, 44, 46

male, 34–7, 41–2, 44, 46, 155, 159,

201, 203

Marazzi and, 152, 155–6, 159, 169n7

oblique, 183

Pasqualino Settebellezze and, 55, 57

Rohrwacher and, 249, 252

subjectivization of, 152

violence and, 201

“Gendering Mobility and Migration”

(Scarparo and Luciano), 136

Genz, Stephanie, 3, 213–14

Ginsberg, Allen, 243

Giordana, Marco Tullio, 173, 188n1

Godard, Jean-Luc, 131, 137, 241, 254

Golini, Vera, 276

Gough, Kathleen, 199, 207n5

Gutierrez, Chus, 226n16

History of Sexuality, The (Foucault),

203, 207n8

Hollinger, Karen, 217, 222

Infascelli, Alex, 173

International Film Festival of Rome,

237

“Invisible Flâneuses: Women and

Literature of Modernity” (Wolff),

136

Invisibles, The, 264

Irigaray, Luce, 34, 37, 41, 209

Italian Cinema from Neorealism to

Present (Bondanella), 2

Italian National Television (RAI), 73,

161, 206, 235n1, 237–8, 263

Johnston, Claire, 3, 33–4, 38, 47n7

Kaplan, E. Ann, 2–3, 34, 42–3, 48n7

Karagoz, Claudia, 7, 103–15, 276

“la meglio gioventù,” 173, 175–6

La sconosciuta, 137

Laviosa, Flavia, 91, 96

Ligabue, Luciano, 174

Lincoln Center’s Italian Film Festival, 237

Lombroso, Cesare, 203

Lorcano Film Festival, 154

Luciano, Bernardette, 136, 265

Lucini, Luca, 173

Maderna, Giovanni, 178

Maggioni, Daniele, 135, 238

Maiorca, Donatella

biography, 206

Purple Sea: figure of Angelo/a, 195–9;

importance of, 204–6; overview,

195–6; patriarchal society, 199–204

Viola di mare, 117n14

Mamma Roma, 135

Marazzi, Alina

critical nostalgia, 166–7

cultural context of work, 152–3

“docu-diary” and, 178–9

early career, 178

feminist themes and, 150–2

interview, 231–5; on archival

material, 231–2; on early career,

231; on female displacement,

233–4; on motherhood, 234–5;

on Un’ora sola ti vorrei, 232–3; on

Vogliamo anche le rose, 233–4

La meglio Gioventù and, 173–6

literature and, 178

overview, 150, 176–7

scholarship on, 7

supplementary material released

with DVDs, 174, 180–2

themes in work, 177–8

Un’ora sola ti vorrei: critical

reception of, 154; form, 154–5;

fragmentation, 157–9; making of,

153–4; narrative structure, 155–7;

opening scene, 54; voiceover, 155–7

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

282

INDEX

Marazzi, Alina—Continued

Vogliamo anche le rose: Anita’s

diary, 162–3; meaning of title,

159–60; opening sequence, 162;

parody and, 161–2; politics in,

165–6; relation to previous work,

160–1; Teresa’s diary, 163–4;

Valentina’s diary, 164–5

Marcellino pane e vino, 115

Mariaini, Dacia, 276–7

Mariaini, Umberto, 67n1

Marrone, Gaetana, 6, 73–85, 277

Masini, Mario, 165

Massey, Doreen, 141

Mastrandrea, Valerio, 255

Maude (cultural association), 1, 254, 258

Mazzacurati, Carlo, 137

McCabe, Janet, 2

McIsaac, Paul, 33, 47n6

McRobbie, Angela, 2, 226n8

Melandri, Lea, 97, 181–2

Menarini, Roy, 107–8, 117n15

Merini, Alda, 122–3, 144n1

mimicry, 64, 66, 162, 197

Minchia di Re (Pilati), 195

Monti, Adriana, 165

Mulvey, Laura, 2–3, 34, 36–8, 47n7,

48n17, 149, 159

Mussolini, Benito, 22–3, 30n25, 34,

38–9, 45, 54, 56, 58, 66–7, 69n11

Negra, Diane, 214

Newport International Film Festival, 154

Nobile, Robert, 271–2

Notari, Elvira

background, 29

Dora Film, 19, 22–3

Dora Film of America, 23–4

film production, 19–21

Gennariello Film, 21–2

lack of scholarship on, 2

overview, 6, 18

themes in works of, 24–9

O’Healy, Aine, 4, 117n20, 137

Ortese, Anna Maria, 247, 250

Parrella, Valeria, 104, 106–7, 109

Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF), 126,

245n1

Pasolini, Pier Paolo, 77, 81, 137, 156,

168n3

patriarchy

Archiburgi and, 89–93, 97

Borelli and, 210, 217, 220, 223

Doane and, 44

guns and, 55–7

Irigaray and, 37

Italian cinema and, 5

Kaplan and, 42–3

Maiorca and, 195–8, 201, 203

Marazzi and, 161, 167, 185

Massey and, 141

Mulvey and, 36–7, 39–40

Notari and, 19

postfeminism and, 215

Spada and, 122

Wertmüller and, 5, 39–40, 42–3,

45–6, 55–7, 59

Wilson and, 142

women’s political countercinema

and, 33

performativity, 54, 56, 63–5, 67, 69n8

Piccioni, Giuseppe, 178, 184

Pickering-Iazzi, Robin, 277

Pietrangeli, Antonio, 241

Pilati, Giacomo, 195, 204

postfeminism

Borrelli and, 212–18, 220

Chick Flicks and, 222, 224

explained, 225n3

film criticism and, 3

Pozzi, Antonia, 123, 125–8, 237, 239–

40, 243, 245

Practice of Everyday Life, The (de

Certeau), 125

Quatriglio, Costanza, 7, 251, 263–72

écosaimale, 267

interview: on documentaries,

264–5; on future, 272; on

Invisibles, 264; on L’isola,

266–70; on Robert Nobile, 271–2;

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

INDEX 283

on Terramata, 270–1; on themes

in work, 265–6; on women’s

portrayal in film, 267–8

Io, qui. Lo sguardo delle donne, 267–8

overview, 263–4

Radner, Hilary, 2, 8, 218, 225n3

Randi, Paola

impact on filmmaking, 7, 121

interview with, 253–61; on

documentaries, 255; on early

career, 254–5; on female gaze,

260; on Into Paradise, 255–7; on

Maude, 258–60; on Milan, 257–8;

on representation, 256

Into Paradise, 253, 255–6

Rohrwacher and, 248

study of women’s films, 251

Reggio Calabria, 121, 247–9, 252

Reggio, Godfrey, 178

Rhys, Jean, 149

Ricci, Chiara, 2, 15–29, 277

Rich, Adrienne, 151, 164, 199–202,

207n4–5

Rich, B. Ruby, 216

Riches, Pierre, 84

Righelli, Gennaro, 19

Ring-Independent Filmmakers of the

New Generation, 173

Rohrwacher, Alice, 7, 121, 247–52, 261

interview: on church, 249–50; on

Corpo Celeste, 248–50; on early

career, 248; on gaze, 249, 252;

on Reggio Calabria, 249, 252; on

women directors, 251

overview, 247–8

Roma, 36

Romito, Patrizia, 90, 93–4, 97

Rossellini, Roberto, 74

Rothko, Mark, 131

ruralism, 56

Russell, Diana, 90, 93

Russell, Ken, 73

Scarparo, Susanna, 136, 178, 265

Scosse (Borelli), 209–10

Se non ora quando (SNOQ), 103,

115n2

Sex and the City, 215–17

Simmel, Georg, 16

Sorrentino, Paolo, 173, 259

Space, Place, and Gender (Massey), 141

Spada, Marina

Come l’ombra, 127–44

death in films of, 124

Deserto Rosso, 122

entrapment and, 136

Forza Cani, 123–6

gaze and, 138–9

Il mio domani, 127–44

interview, 237–45; on Basilico,

240–1; on Come l’ombra, 240–2,

244; on early career, 238; on

Forza cani, 238–9; on gaze, 245;

on Il mio domani, 241, 244–5; on

influences, 241–3; on landscapes,

242–3; on Pozzi, 239–40

“La mia città,” 122, 144

landscape in works of, 131–6

L’Avventura, 122

L’eclisse, 122

Milan and, 124–5, 138–9

mothers in work, 141–2

overview, 121–2

Poesia che mi guardi, 126–30

poetry and, 123

prostitution in works, 136–7

treatment of place, 122

violence and, 137–8

walking and, 143

Sphinx in the City, The (Wilson), 142

Stampa, Gaspara, 1

Summerfield, Giovanna, 263–72, 278

Sundance Film Festival, 247

Swept Away, 33

Tasker, Yvonne, 2, 214

Terragni, Laura, 89, 91

Tola, Vittoria, 97

Torino Film Festival, 154

Tornatore, Giuseppe, 137

“transparence-absence,” 5

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507

284

INDEX

Un ragazzo di Calabria, 115

Valentini, Chiara, 5, 212, 224

Vanzina, Carlo, 3

Venice Film Festival, 115, 130, 237,

240, 253, 263–4

Vesna va veloce, 137

Vesuvio Film, 18–19

Virga, Anita, 195–206, 278

“Visual Pleasure and Narrative

Cinema” (Mulvey), 3, 47n7

Wertmüller, Lina

Love and Anarchy: brothel in,

37–43; cinematography,

35–6; family and, 42; female

characters, 38–40, 43–4;

fetishism and, 38–9; grotesque

in, 40–1, 44; masculinity and,

35–7; plot, 33–4; reflections and,

45–6; themes, 34–5; voyeurism

and, 37–8

Pasqualino Settebelleze: fascism

and, 56–7; gender and, 63–6;

grotesque in, 67; gun in, 55,

60–3; linguistic signs in, 65;

masculinity and, 54–67; plot, 54;

themes, 53–4; women and, 56–7

scholarship on, 1–2, 4, 6

When We Dead Awaken (RIch), 164

Wilson, Elizabeth, 142

Wolff, Janet, 136

Woolf, Virginia, 251

Young, Mallory, 216

Zagarrio, Vito, 173–6, 188n3

Zajczyk, Francesca, 212

Zamboni, Chiara, 178

Zeffirelli, Franco, 74

Copyrighted material – 9781137336507