Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

Viewpoint

New insights into

consumer-led food

product

development

A.I.A. Costa*,1 and

W.M.F. Jongen

&

Product Design and Quality Management–

Agrotechnology and Food Sciences, Wageningen UR,

P.O. Box 8129, 6700 EV Wageningen,

The Netherlands

(e-mail: ana.costa@wur.nl)

This paper builds upon a review of relevant marketing,

consumer science and innovation management literature to

introduce the concept of consumer-led new product

development and describe its main implementation stages.

The potential shortcomings of this concept’s application in

European food industry are described. Contrary to previous

optimistic views, it is put forward that without significant

changes taking place in the mindset of the organizations

involved in Europe’s food R&D, the way forward for

consumer-led innovation strategies in the agri-business

sector will be long and hard.

Introduction

New product development (NPD) is often recommended

as a suitable strategy to build competitive advantage and

long-term financial success in today’s global food markets.

Product innovation is said to help maintain growth (thereby

protecting the interests of investors, employees and food

chain actors), spread the market risk, enhance the

company’s stock market value and increase competitiveness

(Buisson, 1995; Lord, 2000; Meulenberg & Viaene, 1998;

* Corresponding author.

1

Address: Aarhus Business School, MAPP, Center for Research on

Customer Relations in the Food Sector, Haaslegaardsvej 10, DK8210 Aarhus, Denmark. Tel.: C45 89486498; Fax: C45 86150177.

0924-2244/$ - see front matter q 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2006.02.003

Trail & Grunert, 1997; van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998).

Surprisingly, however, the European food and beverage

industry displays much lower research and development

(R&D) investments than industries in other sectors and is

quite conservative in the type of innovations it introduces to

the market. Radically new products are rare (only 2.2% of

total product launches), especially when compared to the

high number of products (an estimated 77% of total product

launches) representing nil or an incremental level of novelty

only that is introduced to the market every year (Avermaete

et al., 2004; Ernst & Young Global Client Consulting,

1999). This approach to innovation, which keeps R&D costs

low and implies a minute technological risk only, does allow

the introduction of a relatively high amount of different

products in a short time span. The large majority of food

products developed in this way cannot, however, be

considered truly new. Moreover, with mere technologybased reductions of processes’ and ingredients’ costs being

frequently marketed as new, enticing benefits to the

consumer, it becomes increasingly harder for buyers to

perceive the added-value of ‘slightly new’ food products

and thus reward incremental innovation (Galizzi &

Venturini, 1996; Grunert, Baadsgaard, Larsen, & Madsen,

1996; Trail & Grunert, 1997).

It is a generally accepted fact that far too many food

product introductions fail. Figures vary widely, but even the

more conservative estimates, encompassing only truly new

products and excluding those that failed before reaching the

marketplace, indicate that 40–50% of new product

introductions are out of retailers’ shelves within a year

(Ernst & Young Global Client Consulting, 1999). This

apparently supports those advocating that few resources

should be committed to discontinuous innovation in food. It

is often said that eating preferences and habits’ slow rate of

change, together with the consequent consumer aversion to

too much novelty in food, constitutes a barrier to genuine

innovation too high to overcome. Nevertheless, consumers’

food consumption behaviour does change, perhaps faster

today than ever. It is also not wise to assume that consumers

all share the same preferences or degree of risk-aversion

concerning innovative products. Given the global character

of food markets today, innovation may, therefore, become

more of a necessity than an option (Galizzi & Venturini,

1996; Grunert et al., 1996; Trail & Grunert, 1997).

Moreover, being conservative does not seem to be paying

off much anymore: me-too products launched in Europe fail

458

A. I. A. Costa, W. M. F. Jongen / Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

(on country average) 18% more often than line extensions

and about 24% more than truly new products (Ernst &

Young Global Client Consulting, 1999).

Consumer-led product development was introduced in

the early 1990s as a market-oriented innovation concept

concerning the use of consumers’ current and future needs

and its determinants in the development of new products

with true added value (Urban & Hauser, 1993). It has been

since repeatedly advocated by several marketing and food

technology experts (Lord, 2000; van Trijp & Steenkamp,

1998), but little has been done to consolidate its theoretical

foundations and establish concrete methodological guidelines for its practical implementation. To our knowledge,

only two applications of consumer-led NPD within the food

industry have been described so far (Grunert & Valli, 2002;

Jaeger, Rossiter, Wismer, & Harker, 2003), each following

its own methodological approach. Additionally, empirical

or case-based studies analysing the advantages and

disadvantages of this innovation strategy vis-à-vis the

conventional NPD practices within the food industry have

not yet been reported.

This article builds upon a review of the relevant

marketing, consumer science and innovation management

literature to describe the economic background and the

theoretical foundations that brought about the concept of

consumer-led new product development. Next, the key

stages of the concept’s practical implementation and the

potential shortcomings of its application within the food

sector are described. Additionally, an attempt is made to

forecast the future of consumer-led food product development in Europe in the current circumstances and to highlight

some of the areas in which more research is necessary to

ensure its prosperity.

The challenges of today’s global food markets

Socio-economic and technological developments

occurring during the last decades in Western society

have triggered the need for a shift of the agricultural and

food industry sectors’ orientation from production to

market. The fact that food markets have become buyer

markets rather than seller markets has several explanations (Grunert et al., 1996; Meulenberg & Viaene,

1998). From the economic perspective, the increase of

disposable income and the decrease in population growth

resulted in the deceleration of the demand for food.

Meanwhile, the scientific and technological developments

of the last half-century gave rise to global-scale food

production and distribution, making an ever-diverse and

ever-increasing food supply almost permanently available

everywhere. This imbalance between supply and demand

decreased the importance of availability and price as

determinants of food purchase and increased the relative

importance of consumers’ choice criteria (Meulenberg &

Viaene, 1998; van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998). Nowadays,

most Western consumers can buy exactly what they want

to eat, instead of only what is readily available or

affordable, and have, therefore, become the driving

element of the food chain.

Due to the significant changes in life-styles and values

taken place in the last 50 years, the nature of food choice

itself has been transformed. Smaller, higher-educated

families, in which both adults work full-time, and

single-person or single-parent households have triggered

a quiet revolution that is gradually doing away with

conventional eating patterns. The growing importance of

values such as quality of life, well-being or protect the

planet’s environment is also exerting influence on the way

consumers perceive and evaluate foods and production

systems, thereby increasingly determining choice (Meulenberg & Viaene, 1998). Western consumers are likewise

demanding more and better information about the food

they eat and how it is produced. They are increasingly

aware of the interdependence between food production,

food consumption, their own health and that of the

environment. This awareness, together with an abundant

and diversified supply, has made consumers highly critical

of, and demanding about, food products’ quality and

safety (Earle, 1997; van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998).

Finally, consumers are more heterogeneous and whimsical

than ever, which makes their food choice harder to

understand and predict (Grunert et al., 1996; Linnemann,

Meerdink, Meulenberg, & Jongen, 1999). To gain a better

knowledge of what consumers want, how their needs

change and how such changes can be promptly addressed

is consequently becoming not only a factor of success for

the agri-food businesses, but ultimately also one of mere

survival. Companies who are able to uncover (or, better

yet, anticipate) demand, deliver against it and communicate this effectively to consumers increase highly their

chances of survival and success in the marketplace (Kohli

& Jaworski, 1990; Urban & Hauser, 1993). This is

particularly true in the context of today’s global food

markets, in which manufacturers and distributors seek to

produce and sell foods to both familiar and unfamiliar

customers in the midst of world-wide competition.

Public health, environmental and sustainability policies

may also bring about the need to influence consumer’s

food choice. This influence can be exerted either by

regulating processes and products (i.e. affecting availability) or by educating consumers about the relation

between food consumption, health and the environment

(i.e. changing the relative importance of choice criteria).

In any case, the food chain will be affected, either directly

or indirectly, and the development of an effective means

of communication between people and organisations

becomes crucial in being able to cope with policy change

(Best, 1991; Meulenberg & Viaene, 1998). If consumers

cannot grasp the need to adjust their behaviour, as well as

the benefits to be gained by such an adjustment, they will

not accept change, let alone behave according to the

policy-makers’ expectations. Similarly, for innovative

A. I. A. Costa, W. M. F. Jongen / Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

technologies to be successfully applied in food production

they must be, first and most, analysed in terms of

perceived consumer value. Carelessly pushing them

forward simply because they might be highly advantageous for the food chain’s actors can, in spite of all

efforts, do more harm than good (Best, 1991; Fuller, 1994;

Meulenberg & Viaene, 1998).

Market-orientation and consumer-led new product

development

Agriculture and food enterprises clearly need to

develop further their understanding of the markets in

which they operate and skilfully apply this knowledge in

the creation of competitive advantage. The most adequate

way to achieve this is probably through the implementation of the market-orientation concept (Grunert et al.,

1996). Market-oriented companies are those which have

committed themselves to the continuous generation and

internal dissemination of market intelligence relevant to

the current and future needs of their customers, as well as

to the continuous improvement of their responsiveness to

such needs (Kohli & Jaworski, 1990). Although a positive

relationship between market-orientation and business

performance has been established for several types of

industries (Avlonitis & Gounaris, 1997; Han, Kim, &

Srivastava, 1998; Slater & Narver, 2000), not much is

known about the level of market-orientation of European

food companies and how it influences their performance.

One could expect the current scenario of high market

instability, increasing competitiveness, slowing economy

and modest technological development to be rather

favourable to a market-oriented approach (Kohli &

Jaworski, 1990). Nevertheless, few studies addressing

this topic indicate that the generation of consumer

intelligence by the food industry, a necessary but not

sufficient condition for market-orientation, remains very

scarce and mostly accidental. In practice, most food

companies, with the probable exception of some large

multinationals, rely on retailers to obtain information

about their end-users. This leads to the assumption that

truly market-oriented food companies are still rare in

Europe (Avermaete et al., 2004; Harmsen, 1994;

Meulenber & Viaene, 1998; Trail & Grunert, 1997).

Studies in innovation management have looked closely

at the relationship between market-orientation and new

product development (NPD), suggesting that these

organisational processes could greatly benefit from each

other (Grunert et al., 1996; Kok, Hillebrand, & Biemans,

2001). On one hand, it has been sufficiently demonstrated

that market-orientation is a critical factor in successful

product development and innovation processes (AtuaheneGima, 1995; Cooper & Kleinschimdt, 1994; Lukas &

Ferrel, 2000; Wind & Mahajan, 1997). On the other hand,

it is rather straightforward to conclude that the continuous

adaptation of a company’s products and services to the

market (i.e. NPD) is a pertinent way of formulating the

459

market-orientation concept. NPD can be seen as an

organisational process in which information about the

market and its actors is gathered, diffused, assimilated and

returned in the shape of a new product or service.

Consequently, a market-oriented approach to product

development implies a sound understanding of:

1. The fact that both technical knowledge and market

information are necessary to run effective product

development processes;

2. The way market information can be gathered,

disseminated and combined with technical knowledge

to develop successful products (Grunet et al., 1996).

It is also thought that the implementation of marketorientation in innovation and NPD processes can be a

crucial step in leading the remainder of the organisation to a

more market-oriented conduct (Kok et al., 2001).

The concept of consumer-led new product development

can be viewed as a market-oriented innovation strategy

developed specifically for the manufacturers of consumer

goods, as it focuses on the share of market intelligence

pertaining to the end-users. It is an integrated concept

concerning the application of consumers’ current and future

needs, and its determinants, in the development of

innovative products with true added value (Grunert et al.,

1996; Lord, 2000; Urban & Hauser, 1993; van Trijp &

Steenkamp, 1998). Its main pillars are:

– Consumer needs should be the starting point of NPD

processes;

– NPD should aim at the fulfilment of consumer needs and

the realisation of consumer value rather than at the

development of products or enabling technologies per se;

– Given that increased sales and satisfactory returns on

investment can only be achieved if consumer needs are

effectively identified and satisfied, the measure of

success of a NPD process should be the degree of fit

between the new product and the needs of the targeted

consumers.

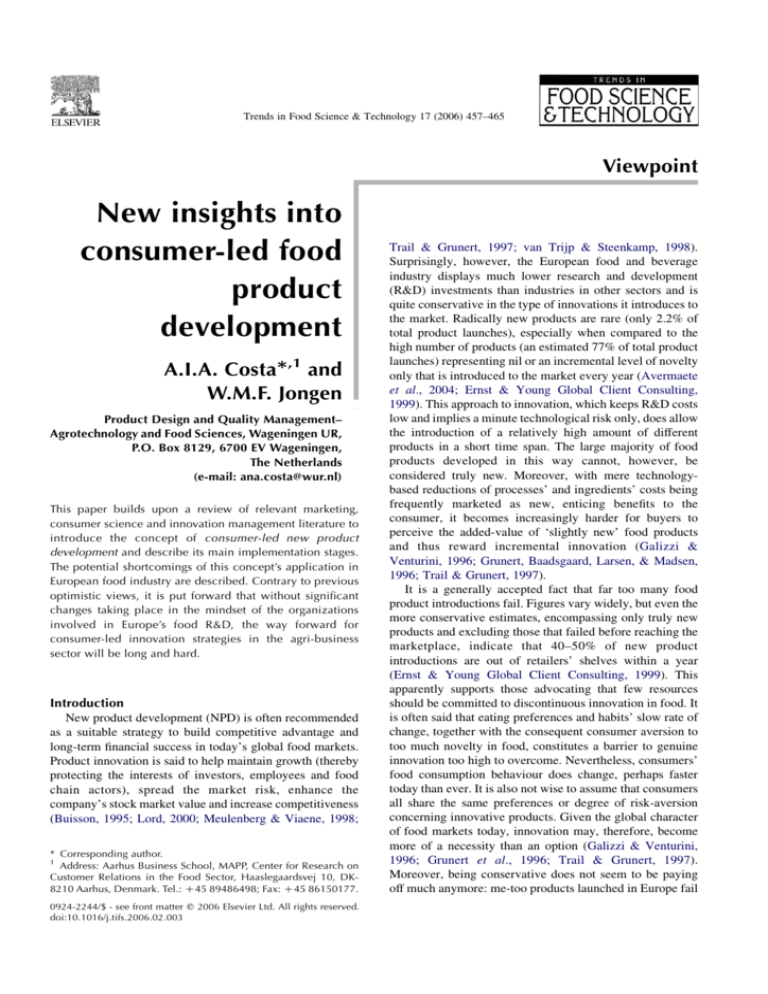

The key stages in the formulation of the consumer-led

NPD concept follow closely a market-oriented approach:

need identification, idea development to address the need,

product development to substantiate the idea and the

product’s market introduction to communicate the

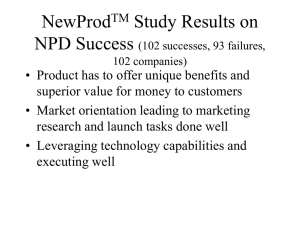

fulfilment of a need (Urban & Hauser, 1993) (Fig. 1).

An effective ability to translate subjective needs (e.g.

healthy or convenient) into objective product specifications is essential for the realisation of the satisfaction of

consumer needs through the development of a new

product. Concurrently, marketing strategies communicating the existence of a new or improved product which

satisfies consumer needs in a distinctive and superior way

must be conceived. It is thought that such a consumer-led

approach to product development can greatly increase the

likelihood of success of innovation processes (Dahan &

A. I. A. Costa, W. M. F. Jongen / Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

460

Consumer research

R&D/Production

Opportunity identification

Market definition

Idea generation

Consumer

needs

Product

concept

Go

No

Product design

Con sumer needs

Sales forecasts

Product positioning Engineering

Segmentation

Marketing mix

Product

and image

No

Go

Testing

Advertising and product testing

Pre-test and pre-launch forecasting

Test marketing

Go

No

Market communication

Introduction

Fig. 1. The consumer-led new product development concept.

Hauser, 2002; Grunert et al., 1996; Urban & Hauser,

1993; van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998; Wind & Mahajan,

1997).

If one accepts that the European food industry currently

possesses a low degree of market-orientation, the benefits of

introducing consumer-led NPD become obvious. Having in

mind the socio-economic constraints earlier described, it is

relatively simple to conclude that European food production

chains must increasingly rely on the industry’s ability to

continuously develop innovative and differentiated products

with added consumer value. Therefore, any approach that

promotes the efficiency and effectiveness of product

innovation processes is welcomed (Grunert et al., 1996;

Meulenberg & Viaene, 1998; van Trijp & Steenkamp,

1998). Moreover, seeing that consumer-led NPD is a

tangible way of putting market-orientation into practice,

its implementation should lead to a better financial

performance of the agri-business sector as a whole.

Key stages in a consumer-led NPD process

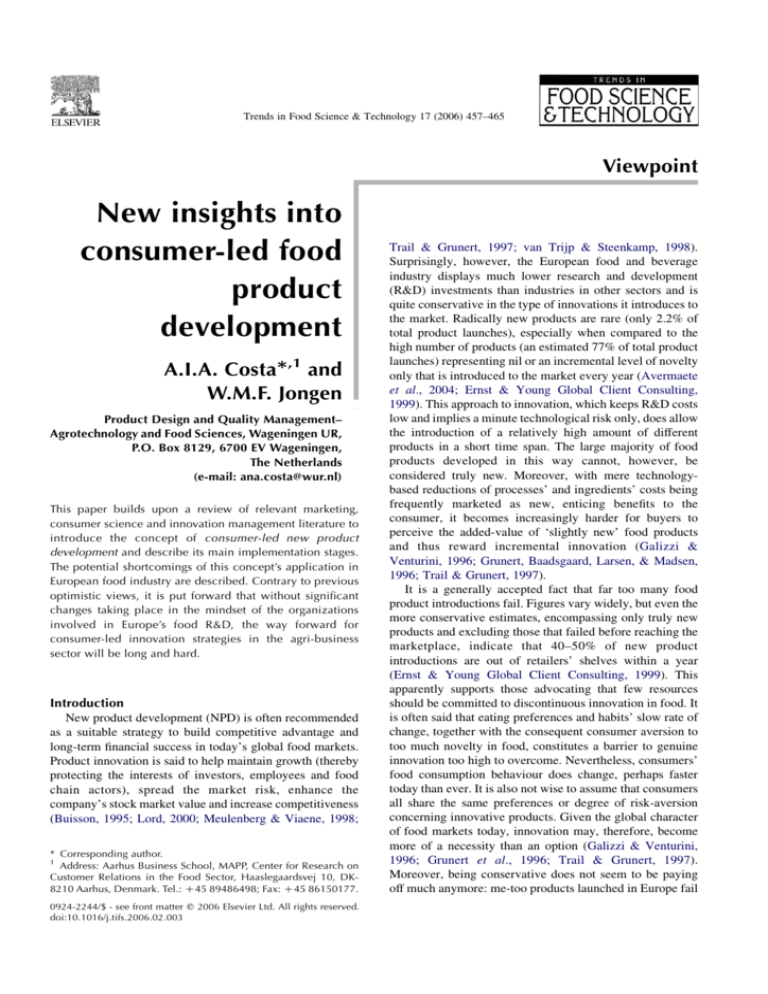

Fig. 2 depicts the key stages of a consumer-led NPD

process. The opportunity identification stage aims at

defining the target markets in which management expects

NPD efforts to be profitable and generating product ideas

which can successfully compete in these markets. At this

stage, supported by a thorough understanding of its own and

the competitors’ core competences and unique strengths,

companies should conduct a strategic assessment of which

technological platforms might provide a solid basis for

NPD. If, given the outcome of such an assessment,

potentially attractive markets and ideas can be found, the

decision to initiate the development process can take place

(Dahan & Hauser, 2002; Robinson, 2000; Urban & Hauser,

1993; van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998).

Launch planning

Tracking the launch

Go

No

Life-cycle management

Market response analysis

Competitive monitoring & defence

Innovation at maturity

Reposition

Fig. 2. The consumer-led new product development process

(adapted from Urban & Hauser, 1993).

The design stage seeks to identify the key consumer

benefits the new product is to provide, as well as the

positioning of these benefits via-à-vis the competition. It is

thus at this stage that the development of the physical

product, the correspondent marketing strategy and the

service policy takes place (Urban & Hauser, 1993; van

Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998).

Fig. 3 depicts the main elements of the product design

stage. The strategic information about the target consumers

collected during the opportunity identification stage serves

as primary input for the first design element—opportunity

definition. At this point, the potentially rewarding ideas

selected earlier are submitted to the target consumers’

evaluation. Such an early evaluation is crucial since it

allows for an assessment of the market potential of the

selected ideas to take place before any considerable funds

are committed to the NPD process. Both qualitative and

quantitative consumer research are undertaken at this point.

Qualitative research methods are usually employed first to

identify relevant issues which may need further investigation, while quantitative methods are used at a later time to

establish the expected benefits and their relative importance

in a more precise manner (Urban & Hauser, 1993; van Trijp

& Steenkamp, 1998). Next, a list of benefits and their

relative importance to consumers is conveyed into a

A. I. A. Costa, W. M. F. Jongen / Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

Voice of the Consumer

Consumer Research

1. Qualitative, to identify issues

2. Quantitative, to supply input for

the modelling of consumer aspects

Summary of consumer aspects

Perception

Product

Preference

Segments

461

Voice of the Company

Opportunity Definition

Opportunity Refinement

•

•

•

•

Marketing

R&D

Engineering

Production

Choice

“What-if” forecasts

• Aggregate individuals

• Awareness and availability

Opportunity Evaluation

Fig. 3. The product design stage (adapted from Urban & Hauser, 1993).

refinement phase, in which the new product starts to take

shape. This is achieved through a careful analysis of the

relationships between consumer perceptions, preferences

and choices, on one hand, and the product’s technical

features on the other. Underlying this analysis is a

conceptual model of consumer behaviour in which

preferences are formed based on the perceptions of the

products’ features and lead, in turn, to choices contingent

upon price and availability (Tybout & Hauser, 1981; Urban

& Hauser, 1993; van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998). Finally, if

the refinement phase was completed successfully, i.e. if it

was possible to design a new product that could potentially

fulfil consumer needs in a superior and unique way, an

evaluation of the design takes place—opportunity evaluation. This evaluation consists of forecasting sales for the

designed product based on the aggregation of the

probabilities of individual consumers’ preferences and

choices. If the estimated market performance complies

with expectations, further development and testing of both

the product and its marketing strategy can occur.

Once the testing of the new product and its marketing

strategy has been successfully concluded (Fig. 2), the

market introduction of the new product takes place. The

monitoring of the target consumers’ and the competitors’

reactions to the new product’s introduction, which might

lead to adjustments in the product and the marketing

strategy, constitutes the final stage of the NPD process, the

so-called life-cycle management (Urban & Hauser, 1993).

Limitations to the application of consumer-led

NPD in European food industry

There are many reasons why food companies decide to

develop and market new products. This decision is often

associated with changes occurring in the food chain

and/or its environment which are not necessarily related to

consumers’ needs (Best, 1991; Fuller, 1994). Upstream

changes in the production chain, like supplier, package or

ingredient modifications, typically imply product and

process reformulations and constitute, thus, a common

motive for food companies to initiate product development. But downstream changes such as alterations in the

distribution channels, introduction of competing products

or internationalisation may also bring about NPD

activities. Finally, developments in the chain’s environment, like the availability of new technologies or

restrictions imposed by governmental and supra-governmental legislation, can trigger innovation efforts too. All

these cases are prototypical of the so-called reactive

approach to NPD, in which food companies try to market

what was developed through advertising and other

marketing efforts rather than developing what consumers

wanted in the first place (Buisson, 1995; Urban & Hauser,

1993). On the other hand, it has by now become clear that

the continuous collection and assimilation of suitable

information about the consumers’ views and needs, since

the very beginning of development until the market

introduction stage and beyond, is an essential feature of

462

A. I. A. Costa, W. M. F. Jongen / Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

consumer-led NPD. This feature, along with the fact that

the concept itself implies taking consumer needs as the

starting point of product innovation efforts, makes of it

the quintessential example of a proactive approach to

NPD (Urban & Hauser, 1993). It would seem then quite

obvious to conclude that, given the current socioeconomic background against which the European food

industry is set, proactive strategies for product innovation

should be more successful than reactive ones. Yet, there is

a major downsize to this reasoning, which is the fact that

there are no published empirical or case-studies demonstrating that proactive strategies are significantly more

successful than their reactive counterparts in the context

of food industry. Being as it is, the motivation to adopt a

proactive approach to food innovation, such as consumerled NPD, relies solely on management’s strategic vision

and a leap of faith. It is, therefore, imperative for

researchers in food innovation management to concentrate

their efforts on clarifying whether or not (and in which

circumstances) consumer-led NPD can lead to products

that are more successful in the marketplace than those

developed through more conventional innovation

strategies.

Understanding consumer needs and reacting effectively

to them is believed by many to be one of the most

important correlates of product development success

(Cooper & Kleinschmidt, 1994; Grunert et al., 1996;

Saguy & Moskowitz, 1999; Urban & Hauser, 1993).

There are those, however, who question the value of

consumer focus in NPD. It has been stated that consumerled development activities, by following closely consumer

needs, encourage incremental innovation in detriment of

the development of truly new products. The main

argument sustaining this view is that consumers cannot

be expected to provide needs about products or

technologies which are yet unknown to them (AtuaheneGima, 1995; Ortt & Schoormans, 1993; van Trijp &

Schifferstein, 1995; Wind and Mahajan, 1997). In line

with this argument, several methodologies, such as

consumer-idealised design (Ciccantelli & Magidson,

1993), problem and lead-users design (Ortt & Schoormans, 1993; von Hippel, 1986), beta-testing (Kaulio,

1998) and information-acceleration (approach which

places consumers in future technological scenarios)

(Urban & Hauser, 1993), have been developed to

overcome this obstacle. More recently, researchers

begun to explore the potential of image-based, webbased and virtual reality technologies to obtain better,

real-time consumer information and involvement in NPD

processes (Dahan & Hauser, 2002; Wind & Mahajan,

1997). It would be advisable also for those active in food

innovation research to explore the ability of these

technological developments to improve the quality of

the consumer intelligence obtained, as well as the cost

efficiency of consumer research methods.

One of the major and most obvious gaps in consumerled food product development is the lack of clear and

concrete guidelines for its effective implementation in

everyday company practices. This deficiency is felt mostly

(but not uniquely) at the early phases of the development

process—opportunity identification and opportunity definition—which are simultaneously the less structured and

the more determinant for the success of new products

(Nijssen & Frambach, 2000; Nijssen & Lieshout, 1995).

Quite suitably, these phases have been named the fuzzyfront end of consumer-led NPD (Dahan & Hauser, 2002).

It is at this fuzzy-front end that the integration of the

appropriate intelligence regarding the market, the competitors and consumers, which is essential for companies to

be able to successfully match their core competences with

demand, must take place (Cooper & Kleinschmidt, 1994;

Grunert et al., 1996; Lord, 2000; Robinson, 2000; Urban

& Hauser, 1993). Nevertheless, it was only very recently

that efforts to compile and test the applicability and

validity of the methods and tools associated with the

fuzzy-front end, in the context of consumer-led food

product design, have taken place (Costa, 2003; van Kleef,

van Trijp, & Luning, 2005). Efforts to extend this line of

research as to encompass methods and tools associated

with the later stages of consumer-led NPD should be

envisaged.

Finally, a somewhat sequential (rather than concurrent,

overlapping or iterative) nature of consumer-led NPD has

been pointed out as a conceptual weakness and a

considerable obstacle to its application in the food

industry (Buisson, 1995; Fuller, 1994; Stewart-Knox &

Mitchell, 2003; van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998). Nevertheless, attempts have been made to improve the realism

and effectiveness of consumer-led NPD, such as with the

funnel (Wheelright & Clark, 1992) and the spiral

approaches (Cusumano & Selby, 1995). Both these

approaches start with a broad range of ideas from several

sources that are later winnowed to a few high-potential

concepts, some of which will, in turn, be ultimately

developed and launched. The underlying assumption is

that it is less expensive (and more effective) to screen

many alternative concepts at an early stage than to modify

one product during testing and pre-launch. The latest and

most holistic approach has been suggested by Dahan and

Hauser (2002)—the end-to-end NPD process—with the

aim of developing new product platforms within a prespecified market environment. This concept combines the

advantages of the stage-gate approach (Rudolph, 1995), in

which developers must justify their selection of the most

promising option at each NPD stage, with those of the

funnel approach. The end-to-end approach integrates the

different development stages and takes into account

environmental influences, such as those related to the

supply chain or human resources’ expertise, as well as

trade-offs between time-to-market, customer satisfaction

and costs. Whether these holistic approaches could also be

A. I. A. Costa, W. M. F. Jongen / Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

successfully applied in the context of food product

development remains to be demonstrate, thereby posing

a very interesting challenge to researchers in the area of

food innovation management.

The key issue of effective knowledge and effort

integration in food innovation

A structural weakness of consumer-led NPD in what

concerns its potential application in the food industry is that

this concept does not explicitly address the role of chain

actors other than consumers in product innovation management. Looking at the markets in which food manufacturers

operate today this hardly seems realistic. Several studies

point out that European food companies do involve, at least

on an informal basis, retailers and suppliers in their product

development processes. Furthermore, it is reasonable to

expect that the vertical integration of product innovation

management will greatly increase the chances of new

product success in the marketplace (Ernst & Young Global

Client Consulting, 1999; Kristensen, Ostergaard, & Juhl,

1998; Stewart-Knox & Mitchell, 2003; Trail & Grunert,

1997). The establishment of methods for an effective, chainwide integration of product development activities is,

therefore, an area where considerable improvement could

be made, not only for the benefit of the implementation of

consumer-led strategies but also of food innovation management as a whole.

Unfortunately, difficulties in properly coordinating and

integrating activities in food product development are, by

no means, limited to operations at the chain level. It is

frequently heard among researchers and practitioners of

food R&D that there is very little motivation to move

away from their technology-driven environment and start

paying more attention to consumer needs and proactive

innovation strategies. Such issues are frequently seen as

more of a marketing concern than anything else.

Consequently, marketing and consumer researchers active

in the area of food innovation management who openly

advocate the benefits of changing to a more marketoriented approach in food R&D are often met with

considerable scepticism. What they must also understand

is that food science academia and R&D practitioners have

not been, so far, often required (or encouraged) to think

about how to design and sell an augmented product as the

consumer demands it. Perhaps, a wiser approach is to start

by taking less extreme views on both sides of the issue

and look for ways in which the market-pull and the

technology-push can benefit from each other. For instance,

a food company can make the decision to commit a share

of its resources to the investigation of the market potential

of its innovative product ideas, irrespective of where they

come from, at the earliest stage possible. Or, instead,

decide that consumer research in the context of market

opportunity identification must already take the

463

company’s core technological competences sufficiently

into account (Kok et al., 2001).

On the other hand, there is also a tendency among

marketing scholars and practitioners active in the agribusiness area to overlook the ingenuity and innovation

potential of many of those specialised in exact sciences or

engineering. What cannot be overstated is the fact that those

employed in R&D and production are fundamental

providers of a company’s enabling technologies and core

competences. Given that they are also the ones who will

ultimately create the core product, their expertise and buy-in

is vital to the success of any market-oriented innovation

effort (Urban & Hauser, 1993; van Trijp & Schifferstein,

1995; van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1998). Reinforcing this view

is the recent development of computer and web-based

interface design tools which, instead of conveying the voice

of the consumer from marketing to R&D as in standard NPD

practices, enable technical personnel to contact directly with

consumers throughout the whole design process (Dahan &

Hauser, 2002).

Ultimately, the sustained practice of consumer-led food

product development implies that an effective integration of

the knowledge and efforts of management, marketing, R&D

and production has been achieved. This is a notoriously

difficult feat in any type of industrial organisation, but one

upon which the success of new products in a global

marketplace is crucially dependent (Dahan & Hauser, 2002;

Griffin & Hauser, 1996; Urban & Hauser, 1993; van Trijp &

Steenkamp, 1998).

Final remarks

Contrary to previous, more optimistic visions, this

viewpoint suggests that without significant changes taking

place in the mindset of the organizations involved in

Europe’s food R&D, the way forward for consumer-led

innovation strategies in the agri-business sector will be long

and hard. In this context, we have highlighted what we

perceive to be the three major obstacles to the implementation of this kind of innovation strategies:

(1) The lack of concrete guidelines for the effective

implementation of consumer-led food product development in everyday industry practices;

(2) The sequential nature of consumer-led NPD, in a clear

contrast with the reality experienced by R&D practitioners in their activities;

(3) The lack of intra- and inter-organisational coordination

or integration of R&D and Marketing’s research

activities and know-how.

Nevertheless, the removal of the first two obstacles will

be meaningless unless a serious effort is made to break

down the barriers to intra- and inter-organisational

cooperation within food supply chains. The time has

come to do away with the clan mentality prevailing in the

European agri-business and food-related research by

464

A. I. A. Costa, W. M. F. Jongen / Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

encouraging cross-functional communication, multidisciplinary team work and the development of a common

language for innovation that truly focuses on consumer

needs without neglecting technological know-how. Or

otherwise, we might just as well missed the marketorientation boat altogether.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to this article was carried out with

the financial support of the Portuguese Foundation for

Science and Technology, under the Program PRAXIS

XXI.

References

Atuahene-Gima, K. (1995). An exploratory analysis of the impact of

market orientation on new product performance: A contingency

approach. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 12, 275–

293.

Avermaete, T., Viaene, J., Morgan, E. J., with Pitts, E., Crawford, N.,

& Mahon, D (2004). Determinants of product and process

innovation in small food manufacturing firms. Trends in Food

Science and Technology, 15, 474–483.

Avlonitis, G. J., & Gounaris, S. P. (1997). Marketing orientation and

company performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 12,

275–293.

Best, D. (1991). Designing new products from a market perspective.

In E. Graf, & I. S. Saguy (Eds.), Food product development: From

concept to the market place (pp. 1–28). New York, NY: Van

Nostrand and Reinhold.

Buisson, D. (1995). Developing new products for the consumer. In

D. W. Marshall (Ed.), Food choice and the consumer (pp. 182–

215). Cambridge: Chapman & Hall.

Ciccantelli, S., & Magidson, J. (1993). From experience: Consumer

idealized design—involving consumers in the product development process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 10,

341–347.

Cooper, R. G., & Kleinschmidt, E. J. (1994). Determinants of

timeliness in product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11, 381–396.

Costa, A. I. A. (2003). New insights into consumer-oriented food

product design. Wageningen: Ponsen and Looijen.

Cusumano, M. A., & Selby, R. W. (1995). Microsoft secrets. New

York, NY: The Free Press.

Dahan, E., & Hauser, J. R. (2002). The virtual customer. Journal of

Product Innovation Management, 19, 332–353.

Earle, M. D. (1997). Innovation in the food industry. Trends in Food

Science and Technology, 8, 166–175.

Ernst & Young Global Client Consulting (1999). Efficient product

introductions: The development of value-creating relationships.

Report no. 0264H, the Efficient Consumer Response (ECR)

Europe initiative.

Fuller, G.W. (1994). New food product development: From concept

to marketplace. Montreal: G.W. Fuller Associates.

Galizzi, G., & Venturini, L. (1996). Product innovation in the food

industry: Nature, characteristics and determinants. In G. Galizzi,

& L. Venturini (Eds.), Economics of innovation: The case of food

industry (pp. 133–156). Heiderlberg: Physica-Verlag.

Griffin, A., & Hauser, J. R. (1996). Integrating R&D and marketing: A

review and analysis of the literature. Journal of Product

Innovation Management, 13, 191–215.

Grunert, K. G., Baadsgaard, A., Larsen, H. H., & Madsen, T. K.

(1996). Market orientation in food and agriculture. Boston, MA:

Kluwer.

Grunert, K. G., & Valli, C. (2002). Designer-made meat and dairy

products: Consumer-led product development. Livestock Production Science (72).

Han, J. K., Kim, N., & Srivastava, R. K. (1998). Market orientation

and organizational performance: Is innovation a missing link?

Journal of Marketing, 62, 30–45.

Harmsen, H. (1994). Product development practice in mediumsized food processing companies: Increasing the level of market

orientation. Proceedings of the second EIASM international

product development management conference, Gothenburg,

Sweden (pp. 286-301).

Jaeger, S. R., Rossiter, K. L., Wismer, W. V., & Harker, F. R. (2003).

Consumer-driven product development in the kiwifruit industry.

Food Quality and Preference, 14, 187–198.

Kaulio, M. A. (1998). Customer, consumer and user involvement in

product development: A framework and review of selected

methods. Total Quality Management, 9, 141–149.

Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: The

construct, research propositions, and managerial implications.

Journal of Marketing, 54, 1–20.

Kok, R.A.W., Hillebrand, B. & Biemans, W.G. (2001). Marketoriented product development as an organizational learning

capability: Findings from two cases. Research report no. 02B13.

Groningen: SOM, University of Groningen.

Kristensen, K., Ostergaard, P., & Juhl, H. J. (1998). Success and

failure of product development in the Danish food sector. Food

Quality and Preference, 9, 333–342.

Linnemann, A. R., Meerdink, G., Meulenberg, M. T. G., & Jongen,

W. M. F. (1999). Consumer-oriented technology development.

Trends in Food Science and Technology, 9, 409–414.

Lord, J. B. (2000). New product failure and success. In A. L. Brody, &

J. B. Lord (Eds.), Developing new food products for a changing

marketplace (pp. 55–86). Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Technomic

Publishing Company.

Lukas, B. A., & Ferrel, O. C. (2000). The effect of market orientation

on product innovation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science, 28, 239–247.

Meulenberg, M. T. G., & Viaene, J. (1998). Changing food marketing

systems in western countries. In W. M. F. Jongen, & M. T. G.

Meulenberg (Eds.), Innovation of food production systems:

Product quality and consumer acceptance (pp. 5–36). Wageningen: Wageningen Pers.

Nijssen, E. J., & Frambach, R. T. (2000). Determinants of the

adoption of new product development tools by industrial firms.

Industrial Marketing Management, 29, 121–131.

Nijssen, E. J., & Lieshout, K. F. M. (1995). Awareness, use and

effectiveness of models and methods for new product development. European Journal of Marketing, 29, 27–44.

Ortt, R. J., & Schoormans, J. P. L. (1993). Consumer research in the

development process of a major innovation. Journal of the

Market Research Society, 35, 375–387.

Robinson, L. (2000). The marketing drive for new food products. In

A. L. Brody, & J. B. Lord (Eds.), Developing new food products for

a changing marketplace (pp. 19–53). Lancaster, Pennsylvania:

Technomic Publishing Company.

Rudolph, M. J. (1995). The food product development process.

British Food Journal, 97, 3–11.

Saguy, I. S., & Moskowitz, H. R. (1999). Integrating the consumer

into new product development. Food Technology, 53, 69–73.

Slater, S. F., & Naver, J. C. (2000). The positive effect of a market

orientation on business profitability: A balanced replication.

Journal of Business Research, 48, 69–73.

Stewart-Knox, B., & Mitchell, P. (2003). What separates the winners

from the loosers in new product development? Trends in Food

Science and Technology, 14, 58–64.

Trail, B., & Grunert, K. G. (1997). Product and process innovation in

the food industry. London: Chapman & Hall.

A. I. A. Costa, W. M. F. Jongen / Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 457–465

Tybout, A. M., & Hauser, J. R. (1981). A marketing model using a

conceptual model of consumer behaviour: Application and

evaluation. Journal of Marketing, 45, 82–101.

Urban, G. L., & Hauser, J. R. (1993). Design and marketing of new

products (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

van Kleef, E., van Trijp, H. C. M., & Luning, P. (2005). Consumer

research in the early stages of new product development: A

critical review of methods and techniques. Food Quality and

Preference, 16, 181–201.

van Trijp, H. C. M., & Schifferstein, H. N. J. (1995). Sensory analysis

in marketing practice: Comparison and integration. Journal of

Sensory Studies, 10, 127–147.

465

van Trijp, H. C. M., & Steenkamp, J. B. E. M. (1998). Consumeroriented new product development: Principles and practice. In

W. M. F. Jongen, & M. T. G. Meulenberg (Eds.), Innovation of

food production systems: Product quality and consumer

acceptance (pp. 37–66). Wageningen: Wageningen Pers.

von Hippel, E. (1986). Lead users: a source of novel product

concepts. Management Science, 32, 791–805.

Wheelright, S. C., & Clark, K. B. (1992). Revolutionizing product

development. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Wind, J., & Mahajan, V. (1997). Issues and opportunities in new

product development: An introduction to a special issue. Journal

of Marketing Research, 34, 1–12.

![Your [NPD Department, Education Department, etc.] celebrates](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006999280_1-c4853890b7f91ccbdba78c778c43c36b-300x300.png)