The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax: A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

A policy white paper on the Texas Franchise Tax

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

January, 2013

2

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

For more information about any of the recommendations contained in this document, please contact

the Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute:

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

P.O. Box 2659, Austin, TX 78768

(512) 474-6042

www.txccri.org

The contents of this document do not represent an endorsement from any individual member of the

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute Board of Directors.

There may be some policy recommendations or statements of philosophy that individual members are

unable to support. We recognize and respect their position and greatly appreciate the work of everyone

involved in the organization.

Copyright 2013 Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute, all rights reserved.

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

3

4

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

Page 9

Creation and Evolution of a Tax

Page 9

The Franchise Tax Overhaul: The “Margins” Tax

Page 12

Fiscal and Economic Effects of the Franchise Tax

Page 13

The Franchise Tax, Property Tax, and School Funding

Page 18

Recommendation and Economic Impact

Page 20

Conclusion

Page 22

About the Author

Endnotes

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

5

6

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

Executive Summary

Despite the state’s reputation for being low-tax and business friendly, Texas has the strangest hybrid tax

in the nation. Not quite an income tax and not quite a gross receipts tax, the franchise “margin” tax is a

residue of the Progressive Era. At that time, and perhaps now, corporations were seen as evil entities

lurking about, taking control of government and peoples’ lives. Now, the franchise tax is mainly a

convenient way to hide taxation from the bulk of Texans who have to live with diminished opportunities

due to this tax’s myriad negative economic effects.

The franchise tax negatively affects business and jobs by making Texas less competitive with other states

than it otherwise would be, pushing up costs artificially and discouraging the hard work of investing,

innovating and taking the risks involved in building a business. The franchise tax adds to the risk of doing

business in Texas because even a small rate change can have profound financial effects. The franchise

tax distorts business decisions by encouraging business owners to avoid certain legal ways of organizing,

often by keeping businesses small. This tax also builds on itself through the supply chain, multiplying on

itself and distorting relative prices, causing the Texas economy to be less efficient than it otherwise

could be.

Complexity does not just present risk; it also presents opportunity - the wrong kind of opportunity. Like

the income tax, the franchise tax draws lobbyists who seek favors for their clients through specialprivilege tax breaks. The complexity of the system necessitates the hiring of tax specialists so that

companies can defend themselves against an audit. Consequently, small businesses who can less easily

afford such specialized services are disadvantaged by the franchise tax relative to big businesses.

Ultimately, the franchise tax represents a failure on the part of Texas government. It is a failure of our

courts who have forced the creation of a convoluted school finance system that encourages ever-rising

property taxes that the Legislature then feels obligated to mitigate through enhanced state revenues. It

is a failure to confront the inefficiency of the public education system and to face down the illogical

decisions of the courts.

Each of these problems points to a simple solution: it is time for the Texas Legislature to abolish the

franchise tax.

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

7

8

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

Introduction

Texas has the reputation of being a low-tax state, a reputation that is well-earned. According to the Tax

Foundation, in 2010 Texas had the sixth lowest state and local tax burden. At one time, Texas’ tax

burden regularly ranked second or third lowest but since the late 1980s it has consistently ranked fifth

to seventh. Those with even lower burdens as measured by the Tax Foundation include Wyoming, South

Dakota, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Alaska.

Like Texas, Wyoming and Tennessee have no personal or corporate income tax. Texas, however, does

have a unique tax among the states that comes very close to, and may even be worse than, a corporate

income tax. Texas’ franchise tax, or “margins tax” as some have called it since the franchise tax reform in

2006, is a complex tax whose computation requires the same information as that required for the

income tax. But to avoid entanglements with the Texas Constitution which forbids a personal income tax

unless approved by voters, the Legislature built a clever and unique tax that sidesteps the income tax

label.

In many ways, today’s Texas franchise tax defies the character of the state of its origin. Many Texans

take pride in their small-government state. Self-sufficiency and individualism seem incompatible with big

government, which induces people to believe that someone else will take care of them when times are

tough.

And yet, Texas has a tax - the franchise tax - that looks an awful lot like a tax from a big government

state. After all, the franchise tax instructions for the tax year 2012 comprise a booklet 26 pages long,

often indecipherable to the layman, and often requiring the services of a Certified Public Accountant.i

It is a wonder that such an onerous tax exists in Texas. One purpose of this paper is to describe the

franchise tax’s origins and how it came to be the tax that it is today, especially in the context of school

finance. The current form of the franchise tax also has interesting and potentially profound economic

implications. Many of these are quite negative despite Texas’ recent strong economic showing among

the states. These effects will be analyzed and quantified to some degree, with an eye toward eliminating

the Texas franchise tax.

Creation and Evolution of a Tax

Prior to World War I, the burden of government relative to GDP was quite small. The federal, state, and

local government burden amounted to considerably less than 10 percent of GDP:

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

9

With government so small, the form of taxation mattered very little. The property tax in a state like

Texas funded both local roads over which horse-drawn wagons traveled, as well as public schools, which

cost relatively little. Taxes on rail travel, spirits, and other various operations were low, although

economic growth saw these revenues increase so rapidly at times that policymakers hardly knew what

to do with the money.

Governor James Stephen Hogg (served 1891-1895) proposed a franchise tax to be assessed on

corporations. Hogg was a product of his time, the Progressive Era. This anti-big business period, which

saw the passage of the 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution creating the federal income tax, was at

least partly a reaction to abuses on the part of government on behalf of big, monopolistic businesses.

Hogg fought railroad subsidies (a worthy cause) in the courts and was a supporter of William Jennings

Bryan, perhaps the most vocal populist of his time.ii

The basic philosophy behind a franchise tax starts with the fact that corporations are artificial legal

entities that are legally treated like individuals. They exist specifically to allow shareholders, the owners

of corporations, to enjoy limited liability, allowing for the pooling of resources that would otherwise

present too much risk. A stockholder’s risk is limited to the value of his stock by law. This is a substantial

advantage granted by the state to these business entities. Owners of other businesses could see all of

their personal assets threatened by creditors should their businesses fail. Therefore, corporations, it is

reasoned, should pay some kind of fee for the privilege of being a limited liability entity.

This reasoning is suspect. First, large enterprises have benefitted everyone by bringing down costs with

economies of scale and other efficiencies. Second, even when there is consolidation in an industry,

economists have found that there is a good deal of competition that benefits consumers. Third,

shareholders are arguably the principle beneficiaries of limited liability and shareholders indirectly

include pensioners and others who have modest incomes. Of course, Texas could just refuse to charter

corporations. Such a refusal and its economic ramifications might bring into focus the primary

beneficiary – corporations or society in general – from this legal treatment.

Whether or not the philosophy of charging corporations a fee for the privilege of being a corporation

was in the mind of Governor Hogg is a different subject. The Progressive Era, however, witnessed the

growth of general distrust of corporations and large trusts. More likely, Governor Hogg saw taxation of

corporations as something that could be leveraged to gain some kind of control over them in the event

that people felt threatened by big corporate interests. Underlying this idea is that government officials,

elected periodically and on a wide range of issues, were better able to determine the economic future

than many individuals voting every day for products of their choice with dollars.

Corporations are actually just a construct to reduce risk for investors so that large amounts of capital

can be assembled to build large companies that have given this country railroad networks, massive

electricity grids, shipyards, skyscrapers, and widespread computer technology. Every business pays

property taxes that help finance roads and education. The people who earn a living through businesses

pay taxes, too. Businesses pay fees that help pay for the infrastructure they use as well. Exactly why

corporations should pay extra taxes is a bit of a mystery when businesses are viewed objectively in this

way.

Though Hogg proposed the franchise tax in 1891, one was not enacted until 1893. It assessed a $10

annual tax on all foreign (non-Texas) and domestic corporations, exempting what we would call nonprofits today. The tax became graduated in 1897 on the basis of capital stock, ranging between $10 and

$50 for domestic corporations and with no maximum for foreign corporations. By 1907, the franchise

10

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

tax was applied to corporate profits under certain circumstances and the minimum tax for foreign

corporations was $25, more than twice the minimum domestic corporation tax of $10. By then, lawsuits

had been filed by out-of-state corporations to keep the state from taxing 100 percent of their capital

stock when only a fraction of these companies’ business was conducted in Texas.iii

For about 94 years after its basic form was settled in 1897, the biggest changes to the franchise tax were

in the rate charged, which increased substantially over the next 70 years. By 1969, the state was

charging an effective rate of $3.25 per $1000 of net capital (stock value minus debt) plus a $2.00 tax on

debt. Rates changed every four years through the 1970s and 1980s as the tax evolved in response to

changing accounting methodologies and revenue needs of the state. In 1991, however, a major change

to the franchise tax occurred. That year it was altered to effectively become a corporate income tax.

Beginning in 1992, corporations paid the greater of a $2.50 per $1,000 tax on capital or 4.5% on “earned

surplus” (profits plus corporate officer compensation).iv

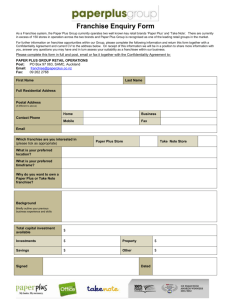

Figure 1: Actual Franchise Tax Revenues Versus

1972 Revenues with Inflation plus Population Growth

$5

Actual Franchise Tax Revenue

Billions of Dollars

$4

1972 Revenue with Inflation + Pop

$3

$2

$1

$0

Sources: Comptroller of Public Accounts, U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, author calculations.

Revenues from the franchise tax have always comprised substantially less than ten percent of all state

tax revenues. In 1972 (the earliest year franchise tax revenues are available online) revenues from the

franchise tax were $129 million (5.5 percent of total taxes). By 1985, after a rate increase, revenues

from the tax had grown to $856 million (8 percent of taxes), but population growth and inflation alone

would have pushed the revenues to only $459 million. In 1992, when revenues from the franchise tax

nearly doubled due to reforms and recovery from a recession, revenues were $1.1 billion (6.9 percent of

all taxes) but inflation and population growth since 1972 would have taken revenues to only $874

million. By 2006, actual franchise tax revenues of $2.6 billion (3.6 percent of total taxes) were more than

double what 1972 revenues adjusted for inflation and population would have been. In 2007, the last

year before the margin tax reforms kicked in, franchise tax revenues grew 21 percent to a record $3.1

billion.

As Figure 1 shows, beginning in the early 1980s during the savings & loan boom, franchise tax revenues

started to outgrow the economy. The legislature got used to this so that when revenues fell due to a

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

11

recession, the capital tax was turned into an income tax. When revenues softened due to the recession

in the early 2000s and worries about the viability of the franchise tax eventually led to its broadening,

the reality was that with economic recovery, the tax’s revenues very quickly recovered. This growth in

franchise tax revenue is especially relevant given that many were complaining by 2006 that the franchise

tax was underperforming partly because of its then-shrinking proportion of total state taxes.v In fact,

except during recessions, the franchise tax has more than kept up with inflation and population growth.

The Franchise Tax Overhaul: The “Margins” Tax

On the heels of failed special legislative sessions in 2005 that attempted to comprehensively reform

school finance law in the state, Governor Perry assembled a blue-ribbon Tax Reform Commission of

business leaders led by former Comptroller of Public Accounts, John Sharp. Hearings were held all over

the state where a familiar story was repeatedly told of how high school property taxes were negatively

impacting businesses and residential property owners.vi

When the franchise tax effectively became a corporate income tax in 1992 with the state’s first taxation

of “earned surplus,” smart tax lawyers and accountants naturally began to find legal ways to avoid the

tax. One such scheme was called the “Delaware Sub” wherein corporations would be formed out-ofstate, most commonly in Delaware, and then do business in Texas as a limited liability partnership, a

form of business that was not taxed under the franchise tax. Dell Computer and Southwestern Bell, both

very large businesses, avoided the franchise tax in this way.vii Another method of avoiding the Texas

franchise tax prior to 2007 was the “Geoffrey” loophole. In this scheme, an out-of-state corporation

would be paid a corporation’s profits in satisfaction of some sort of contractual obligation, technically

eliminating any earned surplus. The “Geoffrey” designation came from the name of the Toys-R-Us

giraffe trademark which was owned by an out-of-state corporation and to which Toys-R-Us technically

paid a fee. Other ways to avoid taxation were devised as well.viii

In 2004, the Texas Comptroller estimated that the closure of the Delaware Sub and Geoffrey methods of

avoiding the franchise tax would garner the state an additional $1.2 billion in revenue over three years.ix

If this estimate is correct, these lost revenues due to the loopholes amounted to 10 percent of the $7.9

billion in franchise tax revenue from 2005 through 2007 and a mere 0.8 percent of all Texas tax

collections in those years.x Despite the fact that franchise tax avoidance schemes had so little impact on

state finances, there was concern that more companies would take advantage of them and render the

franchise tax meaningless.

Another concern at the time was that Texas taxed manufacturing businesses through the property tax

and sales tax more heavily than service businesses. A great deal of time was spent on closing the

loopholes and determining what form the law might take in addressing them and the types of

businesses that would be impacted. There was a desire to provide some relief to manufacturing while

capturing more service oriented businesses.

In the middle of December 2005, the Tax Reform Commission began a whirlwind tour of sixteen

hearings throughout the state. Its last hearing was held in Arlington on March 13, 2006. By March 29 the

commission’s final report was ready for Governor Perry and the general public.xi By the end of May, a

series of bills enacting the tax and adjusting school finance formulas during a special session were signed

into law.

Businesses across the state soon became well aware of the provisions of the new tax. Businesses that

had never had to deal with the franchise tax were captured by the change. These included all

partnerships except general partnerships owned by natural persons, business trusts, and professional

12

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

associations. The tax is applied to total revenues minus the greater of: cost of goods sold, total

compensation, or 30 percent of total revenues. The rate for wholesalers and retailers is 0.5 percent.

Everyone else pays 1 percent. At present, businesses with less than $1 million in total receipts are

exempt from the tax.

With this unique formulation, Texas avoided violating the constitutional prohibition on a personal

income tax. The tax is not quite a gross receipts tax, but it is not an income tax either since an income

tax would allow for the subtraction of all legitimate costs of doing business. The tax was estimated to

bring in over $3 billion per year in additional general fund revenues, but it has never come close to

generating that much additional revenue.xii In fact, one source indicates 2010 revenues fell $2.5 billion

short of estimates at the time the new tax passed into law.xiii

Fiscal and Economic Effects of the Franchise Tax

With rare exceptions, even economists with a philosophically liberal bent will admit that any given tax

has negative economic effects because when you tax something, you get less of it. That is the logic of

“sin” taxes on alcohol and tobacco. And it’s true. If you want less of something, one sure way to

accomplish that objective is to tax it. General George S. Patton fined (taxed, in modern U.S. Supreme

Court parlance) soldiers for slovenliness and the result was that soldiers under his command were not

slovenly. The positive side of taxation comes in certain high-value government services that taxes

finance, like military and police protection of property, courts, and the provision of basic infrastructure.

So, consider what the current Texas franchise tax taxes. It taxes business revenues on an odd net basis

(the greater of cost of goods sold or compensation or 30 percent of revenues), but only if the business is

not a sole proprietorship or a partnership of natural persons, or one of several “passive” limited

partnership entities. In other words, the franchise tax, like a gross receipts tax or an income tax, taxes

the conduct of business, and that is where an economic analysis of the franchise tax’s economic effects

must begin.

The Franchise Tax Discourages Economic Opportunity and Growth

Business revenue is the product of hard work, investment, and risk-taking. Individuals in business must

attract customers by innovating, building customer trust, meeting their needs through investment in

buildings, personnel, and other inputs, and then persuade customers to part with their hard-earned

money by providing value to the customer. All of this is difficult, fraught with risk, long hours of hard

work, discouragement, and determination. Add regulation and business taxes to these material and

psychological costs, and it is not difficult to see that direct taxes on business earnings discourage the

building of businesses.

We are poorer than we otherwise would be on account of direct taxation of business. Consuming is

easy. Producing is hard. Thus, of the two, taxation more easily discourages production. Even if taxes

applied directly to business and income taxes on labor were eliminated but completely offset with taxes

on other things, we would be better off simply because of the negative incentives that direct business

taxes produce. These taxes discourage the effort that goes into building enterprises.

To be sure, Texas is a great place to do business even with the franchise tax. If every state structured

their taxes the same and set the same rates, Texas would still be preferred as a business-friendly

environment. Texas is the second most populous state, so it has plenty of labor resources in addition to

prestigious educational institutions, plentiful natural resources, a strong energy industry, direct ocean

access, and an excellent road network. Add to that a pro-business and pro-private property culture, and

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

13

you get a state with a lot of economic advantages. Nevertheless, the franchise tax is a chink in Texas’

business friendly armor. It is a weakness and a risk, one of only a few for Texas (one of the others being

the property tax), but one that can certainly make a difference when some businesses are weighing

options about the best place for them to invest.xiv

The relative business environments of the states are fluid. For example, three years ago Arizonans

approved a considerable but temporary increase in the state’s sales tax rate by a penny per dollar

purchase. In the last election, Arizonans rejected making the increase permanent and earmarking it for

schools, universities and highways. Arizona now looks more attractive to business investment than it did

a few months ago when polls indicated support for the permanent tax increase.xv Californians just

approved a tax increasexvi that, along with local taxes, puts that state at the top of sales tax rates and at

the top of income tax rates. That state has been bleeding people and businesses and now its business

environment has just been poisoned some more.xvii

Meanwhile, there are states where the political leadership is looking at eliminating income taxes. One is

Oklahoma which, given its position on Texas’ northern border, is ideally situated to snatch industry and

jobs from Texas. Movements in Kansas and Missouri are afoot to do the same. Estate, inheritance, and

property taxes are being considered for repeal in other states as well.xviii Texas cannot afford to rest on

its laurels. The state has recently seen some wonderful press, not just in the U.S. but internationally.xix It

would be easy and understandable for Texas’ leadership to get complacent. Failing to realize and then

do something about the shortcomings of the franchise tax is just the sort of complacency Texas does not

need.

The Texas franchise tax, a direct tax on business activity, discourages business formation and growth. It

discourages hiring. It depresses wages by reducing the amount of money businesses have to reinvest in

capital and labor after they meet expenses.

In fact, at 5.1 percent of Gross State Product, Texas has the 18th highest business tax burden among the

states. Texas’ tax burden by this measure is the same as that of New Jersey, a state with one of the

highest overall tax burdens in the country.xx

What is worse, because Texas has not been able to resolve its school finance issues, the franchise tax

presents a threat to businesses considering investing in Texas. For now, the Texas legislature is

dominated by conservative philosophy, but a school finance crisis in the future with more liberal

leadership could see the franchise tax burden sent to new heights. This risk is an issue for those who

would invest in Texas now. It has to be. Business investments are long-term, and future considerations

are part of the calculus.

Another risk that the franchise tax presents is that a business suffering income losses is still liable for the

tax. This is true of property taxes that impact businesses. It was true of the franchise tax when it only

applied to capital. However, the franchise tax impacts more businesses than in the past and the liability

can be quite substantial: taxing businesses even when they are not profitable adds risk to investing in

building a business in Texas.xxi

The Franchise Tax Distorts Business Decisions

The franchise tax distorts business decisions in ways not unlike the way the national income tax distorts

investment by corporations.xxii Deductions from the tax do not include the cost of capital, but the

choices do include the cost of goods sold or compensation. This naturally causes businesses to neglect

and avoid costs that they cannot deduct. Obviously, a business cannot operate without a roof over its

14

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

head, but maintenance expenses, new machinery, and other expenses like advertising will be reduced

wherever possible. In fact, especially for businesses where compensation is most likely the expense they

will deduct, they have a tax incentive to bring things like advertising, maintenance and perhaps even

legal services in-house. Where before, they might have contracted with other businesses, often small

ones, to carry out these functions for them, these functions, brought in-house, may not be carried out as

efficiently as before.xxiii Ultimately it is the market place – not the state’s tax structure – that should be

the driving force behind business decisions like these.

Sole proprietorships and partnerships made up of natural persons are not taxed under the current

franchise tax. Practically every other business form is, however. The progression of businesses as they

grow often first begins with the simple business forms that are not touched by the franchise tax. The

advantages of incorporation, depending on the circumstances, often include federal tax advantages as

well as protections for owners of the company. With multiple owners, the corporate form of business is

actually contractually simpler and lines of responsibility are often clearer than with many partners in a

partnership. Yet, the Texas franchise tax marginally encourages businesses to hold onto the simple

partnership arrangement as long as possible, potentially to their detriment.

Still another way the franchise tax distorts business decisions is that it has one of the worst

characteristics any tax can have. It builds on itself. This is often called “pyramiding.” Every taxable

business, regardless of where it is in a production chain, is taxed. Since the franchise tax is part of the

cost of doing business, businesses at the beginning of a production chain must build that cost into what

they charge other businesses who buy their products and services. These higher tax-induced costs for

businesses farther down the chain of the production must be built into their prices, impacting their

taxable revenue, and so-on. Thus, at the end of the production chain, the consumer of goods and

services pays prices that build in the cost of the franchise tax multiple times through multiple

businesses.xxiv

Pyramiding from the Texas franchise tax is at its worst the more Texas businesses rely on each other to

supply them. It is for this reason that the franchise tax rate is a low one percent, to minimize its added

costs and do the least possible damage to Texas’ businesses competitiveness. The lower rate of one-half

of one percent, however, is applied to wholesale and retail businesses, where its effects are potentially

the most noticeable to the widest number of Texans, all of whom are consumers at the retail level.

Pyramiding is also most obviously a problem between the wholesale and retail levels, thus its further

minimization.

Because pyramiding can impact relative prices and affect business competitiveness depending on the

location of the businesses from which a Texas business sources its products, the franchise tax is

negatively impacting business to business transactions. Because the tax rate is low and there is a lot of

“noise” in business statistics, the pyramiding effect would be difficult to measure statistically, but it is

there, nonetheless. It makes Texas businesses less competitive as exporters as well. Even though the

franchise tax is only applied to the portion of business sales that occur within the state of Texas, an

exporting business must build in the cost of the franchise tax that is built into its suppliers’ prices and

this is passed on to out-of-state purchasers. In other words, Texas businesses are less competitive than

they otherwise would be.

The Franchise Tax Costs More Than the Tax Itself Due to Its Complexity

Some accountants have doubled their fees due to the sheer complexity of the new franchise tax.xxv It

sounds simple when the tax’s computation is summarized: total revenue minus the greater of cost of

goods sold or compensation or 30 percent of revenues. However, each of these terms has to be defined.

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

15

And because legislators, government rule-makers, and government auditors are not the only clever

people in the world, the definitions have to be very precise. Over time, as loopholes are diligently

searched for and found, these definitions become even more precise but also more complex and

difficult to understand. This is one reason the federal income tax code has become so large, in addition

to the skills of lobbyists creating still more loopholes in that tax system.

Complexity in a tax system has four major effects, all of which are costly to a competition-based

economy - the kind of economy that produces rising standards of living on a sustained basis.xxvi First, as

just noted, tax system complexity adds to the cost of doing business because businesses have to hire

legal and accounting specialists to determine what is owed. Attempts by business managers and owners

to determine tax liability on their own are likely to result in too much tax paid, which negatively affects

their bottom line and competitiveness.

A second effect of complexity, related to the first, is that complexity presents risk. Every tax carries with

it the possibility that the taxing government will audit the taxpayer. Greater complexity increases the

probability that an error will have been made whereby the taxpayer underpaid taxes. The discovery of

underpayment often carries with it additional costs in the form of legal fees, fines, and penalties. This is

one reason accountants increased their fees. They face professional liabilities when they make mistakes

and despite their training, a more complex tax makes it more likely they will err and find themselves

subject to lawsuits and sanctions. Risk adds to costs.

A third issue is rent-seeking. This is the term economists use for pursuing artificial economic advantage.

Very often, businesses in an industry will band together and hire lobbyists to persuade legislators to

allow certain deductions or tax credits that benefit that particular industry, but not other related

competitors. An example might be inflated deductions for certain types of equipment or for hiring

people with certain types of skills. Rent-seeking is costly. Lobbying for special favors produces nothing of

benefit to society as a whole. Also, special tax treatments encourage business decisions that are

distorted by those treatments and resources are, consequently, allocated in ways that true relative

costs, undistorted by taxation, would not allocate them. That is, special tax treatments in a complex tax

system result in greater profits in a rent-seeking industry, attracting more investment than would

otherwise occur. This is detrimental to competitiveness and to society as a whole.

Finally, tax system complexity favors big business over small business as a result of added costs and risks

involved in the tax system. Large businesses can better afford the legal and accounting expertise that it

takes to comply with complex tax systems. Very often, large corporations have such expertise in-house

anyway. These costs are spread over the production output of a large enterprise. Small businesses

cannot afford to hire in-house expertise, so they rely on firms that do not specialize in any particular

small business’s structure and practices. Dealing with a tax system is, to some degree, a quasi-fixed cost.

Fixed costs are the basis on which economies of scale are built. Due to economies of scale, large

businesses are relatively benefitted over small businesses when fixed costs are added artificially through

complex tax systems.

The upshot is that the complex Texas franchise “margin” tax favors big business over small. This effect

was mitigated to some extent by expanding the tax’s exemption so that only businesses with $1 million

or more in revenues must pay the tax.xxvii However, keep in mind that an average full-time employee

costs a business about $58,000 per year in salary and benefits.xxviii If $1 million were spent entirely on

labor, such a business could afford to hire 17 employees. The federal government considers businesses

with many times this number of employees to be small businesses.xxix The franchise tax’s exemption has

its largest effect on only the very smallest of businesses and once a business is subject to the tax, the

cost of compliance only goes down per unit of output as the business becomes much larger. Because the

16

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

franchise tax favors large businesses over small, Texas has fewer new business starts and is the source of

less innovation than would otherwise occur.

The Texas Franchise Tax Destabilizes State Tax Revenues

State-level taxes have often been characterized with the analogy of a three-legged stool. One and twolegged stools are obviously unstable and they fall over. The three legs of a supposedly stable state tax

system include the property tax, which Texas has, the sales tax, which Texas has, and the income tax,

which Texas only partially has in the strange form of the franchise tax, a relatively minor source of

revenue. There are those who want Texas to institute a full-fledged personal and corporate income tax.

Others have proposed general gross receipts taxes or other modified gross-receipts-type taxes in order

to provide what they think will be a stability-producing third leg to the Texas tax system.

In fact, state-level taxes in order of stability are property taxes first, sales taxes second, personal income

taxes third, and corporate income taxes (and their close cousins like the Texas franchise tax) fourth.xxx

Business income and gross-receipts types of taxes, of which the Texas franchise tax is a hybrid, are not a

necessary stabilizing leg to a three-legged tax system. That is, they allow politicians to ply some

constituents more goodies, but the whole edifice is rendered less stable. The chief advantage of these

taxes, especially those that specifically impact business, for those who advocate them is that they are

relatively invisible. Most people do not own businesses. Consequently, they are unaware of how much

they are paying in these taxes and the cost of government is perceived to be lower than it actually is.

Income/gross receipts-type taxes are more volatile than personal income, which is another way of

saying that when the economy is growing, revenues from these taxes grow faster and when the

economy is shrinking, revenues from these taxes shrink faster. There are at least two reasons for this

pattern. First, when times are tough and incomes are down, businesses defend themselves by reducing

expenses wherever they can and one way to do so is to reduce tax liabilities any way they can. Second,

companies do a great deal to hold on to experienced employees and keep from reducing their incomes

but when sales suffer, the net, on which income taxes are calculated, will drop considerably. With gross

receipts taxes, the impact is most keenly felt in business-to-business transactions when businesses

reduce equipment purchases and other investments.

Property values, and the taxes that derive from them, are relatively stable. Values might fall with

recessions and rise with booms, but except when there are price bubbles, property values do not move

nearly as fast as corporate profits and losses or personal income. Sales taxes are relatively stable

because people need things, even when their incomes drop during recessions. On the other hand,

people save so sales taxes don’t rise as much as personal income during good times.

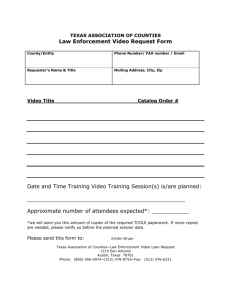

In fact, the relative stability of these three taxes, sales, corporate income, and property taxes, can be

seen by looking at data from Texas as reflected in Figure 2. It shows the annual percentage changes in

franchise tax revenues from 1993 through 2008, mainly the period when it was a corporate income tax.

Figure 2 also shows the same measure for state sales tax revenue and the change in the state’s property

values from 2001 through 2008. The change in property values is shown rather than revenues because

property tax rates, especially for school taxes, changed radically during the illustrated period while the

state’s sales tax and franchise tax rates did not. Besides, the intent is to illustrate how the taxes change

without changes in their rates but due to changes in economic activity that funds these taxes.

As can plainly be seen, the franchise tax rises and falls with a great deal more variability than the sales

tax and property values see even less change than the sales tax. It is clear that the franchise tax is far

less stable than the old mainstays of property taxes and sales taxes.

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

17

Figure 2: Percentage Changes in

the Texas Sales and Franchise Taxes and Texas Property Values

Source: Texas Office of the Comptroller, author calculations

The Franchise Tax, Property Tax Relief, and School Funding

The real purpose underlying franchise tax reform in 2006 had nothing to do with the franchise tax itself.

Instead, it was the perennial problem of school finance and property tax relief. As was stated in the

transmittal letter prefacing the Tax Commission report, it was formed for the purpose of

“recommending reforms to the Texas tax structure that would provide significant and lasting property

tax relief and that also would provide a stable and long-term source of funding for our schools.”xxxi

The subject of school finance and the efforts to make it work is a long one and comprehensive coverage

of the topic is beyond the scope of this paper. Yet a quick review of school finance issues is worthwhile

given the fact that Texas’ tax picture is unlikely to stabilize as long as school finance continues to be the

problem that it currently is. Unfortunately, the creation of the “margin” franchise tax did nothing to

permanently solve the problem, as the school finance system is once again in legal limbo with new

lawsuits having been brought against the state.xxxii

Since the 1980s, there have been lawsuits and rumors of lawsuits regarding the Texas school funding

system almost without ceasing. In 1993, after a series of regular and special sessions with school finance

as a primary issue, the legislature invented the “Robin Hood” school finance system. Though significantly

reformed in 2007, the system’s essentials are still the same. Very simply, schools are financed through

state funds and local property taxes. School boards determine local tax rates. The amount of money a

school district has to spend is determined by state-defined formulas based on student counts, certain

student characteristics, and a school district’s property tax rate. Poor school districts receive money

from the state in order meet the level of funding the formulas define. Rich districts have money

confiscated in order not to go above a certain threshold, also set by formula. Formulas allow for more

spending the higher a district’s property tax rate. The state caps property tax rates of school districts,

but not their total levies.

The unusual thing about this system is how it departs significantly from the way property taxes are

18

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

administered in counties and cities. In these other contexts, when property values go up, cities and

counties can lower rates and spend just as much or even more money, depending on the relative size of

the changes in values versus rates. For example, if values rise by 8 percent but rates fall by 6 percent,

cities and counties have more revenue despite the rate reduction. Or, they can lower rates by the same

percentage as a value increase and spare taxpayers a levy increase.

If a school district’s property values go up and the district reduces its rate, the amount of money it can

spend falls regardless of the relative change in property values versus the rate because state formulas

only reference rates, not property values, for funding purposes. Property values determine only whether

or not a district is subsidized. If a district’s property values rise and the district lowers its rate, or “tax

effort,” the state formulas penalize the district and the total amount of money available to the district to

spend falls. If a school district’s property values rise, the state benefits because rich districts have more

money taken from them and poor districts require less subsidy. When property values fall, on the other

hand, the state must make up the difference - except, of course, when it refuses to do so, which is the

rub that has brought about some of the latest lawsuits.

As a result of lawsuits and court decisions, the legislature has attempted to satisfy demands that: 1)

school funding be equitable to school districts across the state, 2) school taxation be equitable to

taxpayers across the state, 3) property taxes that fund schools be reduced, 4) the state not violate the

constitution’s prohibition of a statewide property tax, 5) local control, including local management of

schools and control of property taxes, be preserved, and 6) the legislature take action to meet the

Constitution’s requirement to “establish and make suitable provision for the support and maintenance

of an efficient system of public free schools” with the goal being a “general diffusion of knowledge.”xxxiii

These measures, like those before them, have only served as a band-aid that has already lost its

adhesion. One problem has to do with the way the courts determine whether the state has a de facto

statewide property tax. They focus only on whether certain school districts have come close to the

maximum legal property tax rate. The courts have paid no attention to the fact that the system

encourages districts to get to that rate. The courts have also paid no attention to the fact that districts

have no discretion in trading off property values against rates.

Finally, of the five lawsuits against the state over school funding, five are concerned with “adequacy”

and/or “equity.” Neither of these two terms appears in the state constitution. Yet, the courts have, in

the past, interpreted the constitution’s call for an efficient system as meaning an equitable system.

However, efficiency and equity mean such different things that economists have written papers about

the tradeoff between the two.

Ultimately, the creation of the new franchise “margin” tax is the responsibility of the Texas Supreme

Court, which forced the Texas Legislature into a round room with no door. The only path appears to be

one in which the legislature and taxpayers are doomed to constantly pass the same scenery over and

over again. At the same time, the Legislature has been unwilling to exert its own authority as a coequal

branch of government, provide its own interpretation of the constitution, and open a new door.

The reformed franchise “margin” tax was fully implemented in 2008 as the Great Recession’s full effects

were being felt. Consequently, this volatile tax, so closely related to income and gross receipts taxes, has

never performed as predicted, bringing in far less revenue than was anticipated. Consequently, the

Legislature had to choose between raising taxes to maintain spending, including on schools, or reduce

spending and maintain economic activity. The Legislature wisely chose the latter. Perhaps this body will

be able to pluck up the courage and set its own path on school finance and simultaneously do the right

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

19

thing with the franchise tax. First and foremost, the Legislature must take care of taxpayers, workers,

and risk takers because without them, the schools have nothing.

Recommendation and Economic Impact

The franchise tax should be eliminated. This could be accomplished over time with a gradual phasedown by systematically reducing rates, although this carries the risk of seeing the eventual elimination

reversed since a future legislature could cancel the draw-down in rate.

The Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute commissioned the Beacon Hill Institute of Suffolk

University in Massachusetts to estimate the economic effects of an outright repeal of the franchise tax.

What BHI found is unsurprising. Elimination of the franchise tax would result in the creation of

thousands of jobs, marked increases in business investment in the state, and dynamic economic effects

that would see increases in collections of other types of taxes including the state’s major state and local

taxes, the sales tax and the property tax. Specifically, Beacon Hill estimates that franchise tax

elimination would see the creation of 40,000 jobs and $300 million in tax revenues as a result of

increased economic dynamism in Texas.

The general public agrees that cutting business taxes has positive benefits for the economy perhaps

because the general public, including job creators and consumers, have a better sense of fundamental

economic principles than they are often given credit for:

While the BHI estimates are big in some ways, they seem rather modest given the elimination of a

nearly $4 billion tax. This is because the Beacon Hill Institute’s model and other economic models are

partly based on assumptions about production input tradeoffs that, over time, have not proven reliable.

Specifically, economic models assume capital (equipment and buildings) are easily substituted for labor.

20

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

While it seems as if this is increasingly the case over time, the reality is that capital investment and labor

force participation have risen together over many decades.

No economic model can fully account for the rise in innovation and entirely new investment that occurs

with fundamental changes in incentives that can occur with the elimination of an entire tax. In Beacon

Hill’s case, the job and business dynamic effects are largely a result of the private sector being allowed

to hold on to more money, not as a result of the fundamental changes in incentives that will occur. In

addition, the production relationships assumed in the model actually presume that franchise tax

elimination will have a tendency to cause a loss of jobs. This is because the model assumes the franchise

tax is entirely a capital tax and when the cost of capital is reduced by reducing taxes, capital will be

relied on more for production and labor becomes less attractive to business.

All of the assumptions in the Beacon Hill economic model are reasonable when considering policy in

limited confines and in short run circumstances. But in an economy the size of Texas’ and especially over

time the dynamic effects of eliminating a franchise tax are likely to be much larger than Beacon Hill

estimates. In fact, job creation is likely to be much larger, probably by a factor of two to three times the

Beacon Hill estimate. Dynamic tax effects - the increase in other taxes as a result of franchise tax

elimination - are likely to be two to three times greater as well. While these effects are not likely to

completely offset the state’s revenue losses as a result of franchise tax elimination, they will mitigate

those losses considerably.

Distributional Issues with Franchise Tax Elimination

Some will argue that eliminating the franchise tax, especially if it is offset with a broadening of the sales

tax, will hurt the poor. This objection is based on who, as best we can identify, directly pays the tax.

However, tax impacts are vastly more subtle and complex than who cuts the check. That is because

taxes have incentive effects that cause various parties to change their behavior, sometimes in ways that

can be very difficult to predict.

For example, during the administration of President George H.W. Bush a federal luxury tax was assessed

on fur coats, private aircraft, yachts, and jewelry in order to make the rich “pay their fair share.” Later

studies showed that the U.S. government actually lost money on this tax because the middle-income

people who lost their jobs due to this tax put more demands on government coffers than the tax ever

contributed.xxxiv

When people use the terms “regressive” and “progressive” to describe a tax they are using words with

loaded connotative meanings that have historically been used for the propaganda value. That value has

only been enhanced by the use of these words in economics and other public policy textbooks.

The real issue in taxation that must be considered is how much damage one tax does to an economy as

opposed to another tax. As noted above, every tax has negative effects; those negative effects are offset

by the positive effects of government services. The goal should be to maximize the difference between

the negative and the positive by choosing a tax system with the least negative effects and government

spending with the greatest positive effects.

Also noted above, income/gross receipts taxes like the franchise tax have profound negative economic

effects because they tax production. A sales tax imposes far less in negative incentive effects and,

therefore, is a less costly tax. That means that even if lower income people pay a higher proportion of

their income to a sales tax than they do to a franchise tax, they still come out ahead because they are

more likely to have jobs and the independent incomes to pay the sales tax than when income/gross

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

21

receipts taxes are relied upon. Even Texas’ own tax incidence report shows that lower income

individuals bear the burden of a higher percentage of the franchise tax than the sales tax.

Conclusion

The Texas franchise tax is a tax whose time has come to be eliminated. There was never a sound basis

for its creation in the first place hailing all the way back to the 1890s. This already complex tax was

morphed into an even more complicated corporate income tax in the 1990s only for the purpose of

increasing taxes on Texans in as invisible a way as possible. It was morphed again into the very complex

margin tax for similar reasons in 2006 in order to attempt, yet again, to paper over a failed school

finance system.

The state can, if lawmakers choose to do so, at least partly offset some of the reduced revenue from a

franchise tax elimination with changes in spending, in addition to the dynamic revenue effects of

eliminating a tax that discourages economic activity. Overall, eliminating the franchise tax in Texas

would be a big win for the state and would cement its economic leadership status in the nation for years

to come.

22

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

About the author:

Byron Schlomach is an economist and works as the Director of the Center for Economic Prosperity at the

Goldwater Institute. He has 15 years of experience working in and around state government. He has

researched and written on tax and spending policy in Texas and Arizona in addition to studying

transportation, health care, and education policy. Byron’s writings have appeared in National Review

Online, Business Week online and numerous Texas and Arizona newspapers. He is a graduate of Texas

A&M University.

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

23

ENDNOTES

i. Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, 2012 Texas Franchise Tax Report Information and Instructions,

Form 05-396 (Rev.3-12/2), available at http://www.freeownersmanualpdf.net/ebook/texas-franchisetax.pdf

ii. “James Stephen Hogg,” Handbook of Texas Online (Texas State Historical Association),

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fho17.

iii. Edmund Thornton Miller, A Financial History of Texas, (Austin, TX: Bulletin of the University of Texas,

no. 37, 1916), 311-313.

iv. Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Sources of Revenue Growth 1972-2003 (Austin, TX: State of

Texas, 2004), 68, http://www.window.state.tx.us/taxbud/sources/sources2004.pdf.

v. Revenue numbers come from the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, the federal Census Bureau,

and the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics in addition to author calculations.

vi. Commercial property taxes in Texas remain quite high compared to all but a handful of states. See

Minnesota Taxpayers Association and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 50-State Property Tax Comparison

Study (Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Taxpayers Association, April, 2012),

http://www.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/significant-features-propertytax/upload/sources/ContentPages/documents/Pay_2011_PT_Report.pdf.

vii. “Blowing up the Delaware Sub,” The Economist, March 6, 2003,

http://www.economist.com/node/1622832.

viii. Understanding the Texas Franchise — or “Margin”—Tax (Austin, TX: Texas Taxpayers and Research

Association, newsletter, October 2011),

http://arlingtontx.com/images/uploads/Margins_Tax_Review_TTARA_102011.pdf.

ix. Carole Keaton Strayhorn, Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, letter to Texas Senator Steve Ogden,

April 28, 2004, http://www.window.state.tx.us/news/40428ogdenltr.pdf.

x. Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Texas Revenue By Source - 1978-2010, and author calculations,

http://www.window.state.tx.us/taxbud/revenue_hist.html.

xi. John Sharp, et.al., Tax Fairness - Property Tax Relief for Texans: Report of the Texas Tax Reform

Commission (Austin, TX: Office of the Governor, March 29, 2012),

http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/ttrc/files/TTRC_report.pdf.

xii. John S. O’Brien, Legislative Budget Board memo to Senator Steve Ogden regarding the fiscal impact

of HB 3, April 27, 2006,

http://www.legis.state.tx.us/tlodocs/793/fiscalnotes/pdf/HB00003E.pdf#navpanes=0.

The newsletter cited in footnote 8 implies lower estimates that this fiscal note were forthcoming at the time.

xiii. Understanding the Texas Franchise — or “Margin”—Tax, 5.

xiv. Byron Schlomach, Lessons from Texas on Building an Economically Healthier Arizona (Phoenix, AZ:

Goldwater Institute Policy Report No. 251, October 17, 2012),

http://goldwaterinstitute.org/sites/default/files/Policy%20Report%20251%20Lessons%20from%20Texa

s_0.pdf.

xv. Danielle Verbrigghe, “Education sales tax measure doesn't get passing grade,” Tucson Sentinel.com,

November 6, 2012,

http://www.tucsonsentinel.com/local/report/110612_voters_reject_prop_204/education-sales-taxmeasure-doesnt-get-passing-grade/.

xvi. Mike Rosenberg, “Proposition 30 wins: Gov. Jerry Brown's tax will raise $6 billion to prevent school

cuts,” Silicon Valley MercuryNews.com, November 6, 2012,

http://www.mercurynews.com/elections/ci_21943732/california-proposition-30-voters-split-tax-thatwould.

xvii

. State to State Migration Data 1993 - 2010, The Tax Foundation,

http://interactive.taxfoundation.org/migration/

xviii. Joseph Henchman, “Trend #6: Tax Abolition,” Top 10 State Tax Trends in Recession and Recovery

24

The Texas Franchise “Margin” Tax | Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute

(Washington, D.C.: Tax Foundation Policy Fact No. 208, June 8, 2012),

http://taxfoundation.org/article/trend-6-tax-abolition.

xix. “California v Texas: America’s Future,” The Economist, June 9, 2009,

http://www.economist.com/node/13990207.

xx. Andrew Phillips, Robert Cline, Thomas Neubig, and Hon Ming Quek, Total State and Local

Business Taxes: State-By-State Estimates for Fiscal Year 2011, Council on State Taxation Report (Ernst & Young,

LLP, July 2012), 11, http://www.cost.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=81797.

xxi. Charles G. Anderson, Sr., “New tax presents challenge for independent businesses,” Abilene

Reporter News, April 10, 2008, http://www.reporternews.com/news/2008/apr/10/new-tax-presentschallenge-for-independent/.

xxii

Li Liu, “Do Taxes Distort Corporations’ Investment Choices? Evidence from Industry-Level Data,”

available as pdf download at aeaweb.org.

xxiii

Jonathan Masters, U.S. Corporate Tax Reform (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Council on Foreign Relations

Backgrounder, April 5, 2012) http://www.cfr.org/united-states/us-corporate-tax-reform/p27860#p4.

This publication is focused on the federal income tax.

xxiv. Joseph Henchman, Texas Margin Tax Experiment Failing Due to Collection Shortfalls, Perceived

Unfairness for Taxing Unprofitable and Small Businesses, and Confusing Rules (Washington, D.C.: Tax

Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 279, August 17, 2011), http://taxfoundation.org/article/texas-margin-taxexperiment-failing-due-collection-shortfalls-perceived-unfairness-taxing.

xxv. Don Bolding, “Texas Legislature lifts some 'margin tax' burden off owners,” Killeen Daily Herald, Jul.

12 2009, http://www.nfib.com/nfib-in-my-state/nfib-in-my-state-content?cmsid=49468.

xxvi. A full understanding of this remark can be gained by reading Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson,

Why Nations Fail (New York, NY: Crown Publishers).

xxvii

Don Bolding, “Texas Legislature lifts some 'margin tax' burden off owners,” Killeen Daily Herald, July

12, 2009, http://www.nfib.com/nfib-in-my-state/nfib-in-my-state-content?cmsid=49468.

xxviii

See “Employer Costs for Employee Compensation-June 2012,” News Release, United States Bureau

of Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecec.nr0.htm. The $58,000 figure is computed by

multiplying $28.80 per hour by 40 (full-time workweek) and then that result by 50, assuming 2 weeks

unpaid vacation per year.

xxix

See the Small Business Administration’s sized standards at

http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/files/Size_Standards_Table(1).pdf.

xxx. R. Alison Felix, “The Growth and Volatility of State Tax Revenue Sources in the Tenth District,”

Economic Review (Kansas City, MO: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Third Quarter 2008), 63-88,

http://www.kansascityfed.org/Publicat/Econrev/PDF/3q08Felix.pdf.

xxxi. John Sharp, et.al., Tax Fairness, tranmittal letter.

xxxii. Morgan Smith, “A Guide to the Texas School Finance Lawsuits,” The Texas Tribune, February 29,

2012, http://www.texastribune.org/texas-education/public-education/how-navigate-texas-schoolfinance-lawsuits/.

xxxiii. Article 7, Section 1, Texas Constitution, http://www.constitution.legis.state.tx.us/.

xxxiv

Byron Schlomach, Progressive or Regressive, Is That Really the Question? (Austin, TX: Texas Public

Policy Foundation Policy Perspective, February 2006), http://www.texaspolicy.com/center/fiscalpolicy/reports/progressive-or-regressive-really-question.

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute | A Tax Out of Step and Out of Time

25