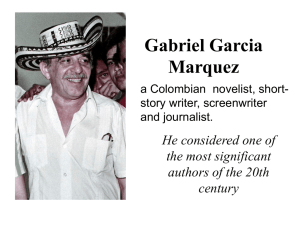

Néstor García Canclini and cultural policy in Latin

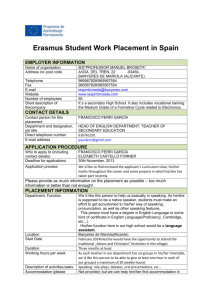

advertisement