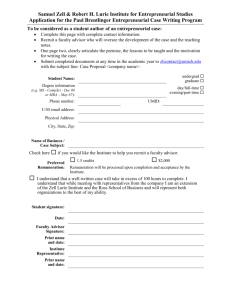

Entrepreneurial Behavior In Large Traditional Organizations

advertisement