REPRESSION, GRIEVANCES, MOBILIZATION, AND REBELLION: A

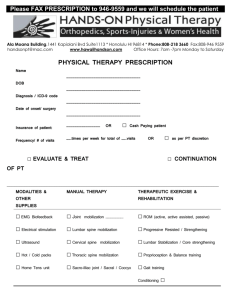

advertisement