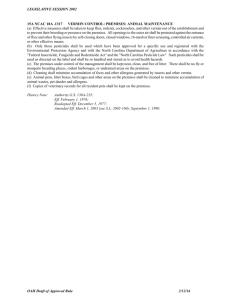

Review of Restricted Premises Act police powers and offence

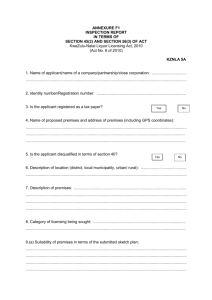

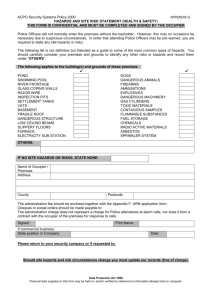

advertisement