Description, justification and clarification: a

advertisement

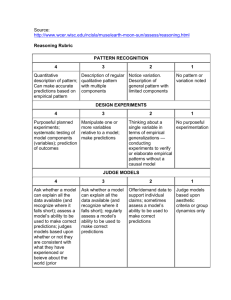

classifying the purposes of research Description, justification and clarification: a framework for classifying the purposes of research in medical education David A Cook,1 Georges Bordage2 & Henk G Schmidt3 CONTEXT Authors have questioned the degree to which medical education research informs practice and advances the science of medical education. clarification studies than were studies addressing other educational topics (< 8%). CONCLUSIONS Clarification studies are uncommon OBJECTIVE This study aims to propose a framework for classifying the purposes of education research and to quantify the frequencies of purposes among medical education experiments. METHODS We looked at articles published in 2003 and 2004 in Academic Medicine, Advances in Health Sciences Education, American Journal of Surgery, Journal of General Internal Medicine, Medical Education and Teaching and Learning in Medicine (1459 articles). From the 185 articles describing education experiments, a random sample of 110 was selected. The purpose of each study was classified as description (ÔWhat was done?Õ), justification (ÔDid it work?Õ) or clarification (ÔWhy or how did it work?Õ). Educational topics were identified inductively and each study was classified accordingly. RESULTS Of the 105 articles suitable for review, 75 (72%) were justification studies, 17 (16%) were description studies, and 13 (12%) were clarification studies. Experimental studies of assessment methods (5 ⁄ 6, 83%) and interventions aimed at knowledge and attitudes (5 ⁄ 28, 18%) were more likely to be 1 Division of General Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota, USA 2 Department of Medical Education, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA 3 Department of Psychology, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Correspondence: David A Cook, Division of General Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Baldwin 4-A, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, Minnesota 55905, USA. Tel: 00 1 507 538 0614; Fax: 00 1 507 284 5370; E-mail: cook.david33@mayo.edu 128 in experimental studies in medical education. Studies with this purpose (i.e. studies asking: ÔHow and why does it work?Õ) are needed to deepen our understanding and advance the art and science of medical education. We hope that this framework stimulates education scholars to reflect on the purpose of their inquiry and the research questions they ask, and to strive to ask more clarification questions. KEYWORDS *education, medical; *research, biomedical; health knowledge, attitudes, practice; clinical competence; evidence-based medicine; teaching ⁄ methods; review [publication type]. Medical Education 2008: 42: 128–133 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02974.x INTRODUCTION Medical education research has witnessed substantial growth in recent years,1,2 yet there are indications that such research may not be informing educational practice. For example, a recent best evidence medical education (BEME) review found weak evidence supporting several conditions for effective high-fidelity simulation but noted that few or no strong studies could be found.3 Cook has argued that virtually all existing research into web-based learning has little meaningful application.4 On a more general basis, Norman noted that curriculum-level research is hopelessly confounded and fails to advance the science.5,6 What is the solution to this seemingly disappointing state of affairs? Authors have, in recent years, called for greater use of theory and conceptual frameworks,7–9 focus on relevant topics,10 more meaningful ª Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2008. MEDICAL EDUCATION 2008; 42: 128–133 Description, justification and clarification Overview What is already known on this subject Despite recent growth in medical education research, there are indications that such research may not be informing educational practice. What this study adds We propose a framework for classifying the purposes of education research, namely, description, justification and clarification. Description studies address the question: ÔWhat was done?Õ Justification studies ask: ÔDid it work?Õ Clarification studies ask: ÔWhy or how did it work?Õ Clarification studies are uncommon among medical education experiments. Suggestions for further research More clarification studies are needed to deepen our understanding and advance the art and science of medical education. outcomes,11–13 and improvements in research methods and reporting.6,14–17 This is sound advice, but research in medical education still suffers from a more fundamental and apparently widespread problem, namely, the lack of a scientific approach. By this we are not implying the absence of scientific study designs and methods, for many studies employ rigorous designs. Rather, we have noted that many research studies in medical education fail to follow a line of inquiry that over time will advance the science in the field. Research that has advanced our knowledge of medicine, as well as our knowledge in other fields such as biology, chemistry and astrophysics, is characterised by a cycle of observation, formulation of a model or hypothesis to explain the results, prediction based on the model or hypothesis, and testing of the hypothesis, the results of which form the observations for the next cycle. Not only are the steps in this cycle – otherwise known as the scientific method – important, but the iterative nature of the process is essential because the results of one study provide a foundation upon which subsequent studies can build. It is through this process that we have come to understand how congestive heart failure develops, how penicillin kills bacteria, and why the planets revolve around the sun. More importantly, this information allows us to predict ways to treat congestive heart failure, design new antibiotics and send rockets to the moon. Unfortunately, this approach seems relatively uncommon in medical education research. Instead, medical educators focus on the first step (observation) and the last step (testing), but omit the middle steps (model formulation or theory building, and prediction) and, perhaps more importantly, fail to maintain the cycle by building on previous results. This in turn limits our ability to predict which instructional methods and assessments will enhance our educational efforts. This could be the underlying cause of recent laments regarding the paucity of useful education research. To better understand this problem and identify potential solutions, it is helpful to consider the purposes of research, which we have divided into 3 categories: description; justification, and clarification. Description studies focus on the first step in the scientific method, namely, observation. Examples would be a report of a novel educational intervention, a proposal for a new assessment method, or a description of a new administrative process. Such reports may or may not contain outcome data, but by definition they make no comparison. Justification studies focus on the last step in the scientific method by comparing one educational intervention with another to address the question (often implied): ÔDoes the new intervention work?Õ Typical studies might compare a problem-based learning (PBL) curriculum with a traditional curriculum, compare a new web-based learning course with a lecture on the same topic, or compare a course to improve phlebotomy skills with no intervention. Rigorous study designs such as randomised trials can be used in such studies but, without prior model formulation and prediction, the results may have limited application to future research or practice. Clarification studies employ each step in the scientific method, starting with observations (typically building on prior research) and models or theories, making predictions, and testing these predictions. Confirmation of predictions supports the proposed model, whereas results contrary to predictions can be just as enlightening – if not more – by suggesting ways in which the theory or model can be modified and improved. Such studies seek to answer the questions: ÔHow does it work?Õ and ÔWhy does it work?Õ Such ª Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2008. MEDICAL EDUCATION 2008; 42: 128–133 129 D A Cook et al research is often performed using classic experiments, but correlational research, comparisons among naturally occurring groups and qualitative research can also be used. The hallmark of clarification research is the presence of a conceptual framework or theory that can be affirmed or refuted by the results of the study. Such studies will do far more to advance our understanding of medical education than either description or justification studies alone. Indeed, description and justification studies, by focusing on existing interventions, look to the past, whereas clarification studies illuminate the path to future developments. Schmidt, during the 2005 meeting of the Association for Medical Education in Europe, presented the results of a systematic survey of the literature on PBL.18 From the 850 studies identified, representing a variety of study designs, he noted 543 (64%) description studies, 248 (29%) justification studies, and only 59 (7%) clarification studies. To build on these findings, we sought to determine the frequencies of study purposes across a variety of educational topics, using systematic methods and focusing on recent literature. To address this aim, we conducted a limited but systematic review targeting experimental studies in medical education. The present study was an extension of a larger systematic review of the quality of reporting of medical education experiments.17 In light of SchmidtÕs findings, we hypothesised that the proportion of clarification studies would be low. Given the experimental nature of the studies sampled, we further anticipated that most study purposes would fall into the justification or clarification categories. were excluded. Based on a review of titles and abstracts of the 1459 articles contained in the 6 journals during the 2-year study period, 185 experiments were identified. Of these we selected a random sample, stratified by journal, of 110 articles for full review. Full text review by pairs of researchers revealed that 5 studies were not experiments, leaving 105 articles for final analysis. For details of this search, including justifications for journal selection and sample size, see Cook et al.17 Each full article included in the study sample was reviewed independently by 2 authors (DAC and GB) and the study purpose was classified as description, justification or clarification using the definitions in Table 1. When more than one purpose was identified in a given article, only the highest level was reported. Studies were also classified according to the topic of medical education addressed by the study. Topics were identified inductively by reviewing each study to identify themes. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus was reached on final ratings. Inter-rater agreement was determined using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs).19 Table 1 Purposes of medical education research studies Description Describes what was done or presents a new conceptual model. Asks: ÔWhat was done?Õ There is no comparison group. May be a description without assessment of outcomes, or a Ôsingle-shot case studyÕ (single-group, post-test only experiment) Justification Makes comparison with another intervention with intent METHODS of showing that 1 intervention is better than (or as good as) We selected the 4 leading journals that focus exclusively on medical education research (Academic Medicine, Advances in Health Sciences Education, Medical Education and Teaching and Learning in Medicine) and 2 specialty journals – 1 for surgery and 1 for medicine – that frequently publish education research (the American Journal of Surgery and the Journal of General Internal Medicine). We systematically searched these journals for reports of experiments published in 2003 and 2004. We defined experiments broadly as any study in which researchers manipulate a variable (also known as the treatment, intervention or independent variable) to evaluate its impact on other (dependent) variables, and included all studies that met this definition, including evaluation studies with experimental designs. Abstract-length reports 130 another. Asks: ÔDid it work?Õ (Did the intervention achieve the intended outcome?). Any experimental study design with a control (including a single-group study with pre- and post-intervention assessment) can do this. Generally lacks a conceptual framework or model that can be confirmed or refuted based on results of the study Clarification Clarifies the processes that underlie observed effects. Asks: ÔWhy or how did it work?Õ Often a controlled experiment, but could also use a case–control, cohort or cross-sectional research design. Much qualitative research also falls into this category. Its hallmark is the presence of a conceptual framework that can be confirmed or refuted by the results of the study ª Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2008. MEDICAL EDUCATION 2008; 42: 128–133 Description, justification and clarification Chi-square test or FisherÕs exact test were used for subgroup comparisons. Analyses were performed with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). RESULTS The most frequent study purpose was justification (75 studies [72%]), followed by description (17 [16%]) and clarification (13 [12%]). Inter-rater agreement for these classifications was 0.48, indicating moderate agreement according to Landis and Koch.20 All disagreements were resolved by consensus. learning and clinical diagnosis (history and examination, diagnosis, evidence-based medicine [39 articles]); instruction for clinical interventions (counselling, prescribing, procedural skills [19 articles]); teaching and leadership (13 articles), and evaluations of assessment methods (6 articles). The purposes of studies varied significantly across educational topics (P = 0.0002) (Table 2). Notably, experimental studies of assessment methods (5 ⁄ 6, 83%) and interventions aimed at knowledge and attitudes (5 ⁄ 28, 18%) were more likely to be clarification studies than were studies addressing other educational topics (< 8%). There were wide differences in study purposes across journals, but these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.08) (Table 3). Five topics of medical education were inductively identified: instruction aimed at knowledge and attitudes (28 articles); instruction for practice-based Table 2 Frequencies of purposes of experimental studies according to educational topic Knowledge ⁄ Clinical Teaching and Clinical leadership Assessment‡ n = 19 n = 13 n=6 Total n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) attitude diagnosis* interventions n = 28 n = 39 n (%) n (%) † Description 4 (14) 9 (23) 1 (5) 2 (15) 1 (17) 17 (16) Justification 19 (68) 29 (74) 17 (90) 10 (77) 0 (0) 75 (72) Clarification 5 (18) 1 (3) 1 (5) 1 (8) 5 (83) 13 (12) Significant difference (P = 0.0002) for comparison of purposes across all topics * Clinical diagnosis: instruction for practice-based learning and clinical diagnosis (history and physical examination, diagnosis, evidence-based medicine) Clinical interventions: instruction for clinical interventions (counselling, prescribing, procedural skills) à Assessment: evaluations of assessment methods Table 3 Frequencies of purposes of experimental studies according to journal of publication Adv Health Teach Learn Sci Educ Am J Surg Acad Med J Gen Int Med Med Educ Med n=5 n=7 n = 23 n = 15 n = 37 n = 18 n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) Description 1 (20) 0 (0) 2 (9) 2 (13) 10 (27) 2 (11) Justification 2 (40) 6 (86) 15 (65) 13 (87) 24 (65) 15 (83) Clarification 2 (40) 1 (14) 6 (26) 0 (0) 3 (8) 1 (6) No significant difference (P = 0.08) for comparison of purposes across all journals Adv Health Sci Educ = Advances in Health Sciences Education; Am J Surg = American Journal of Surgery; Acad Med = Academic Medicine; J Gen Int Med = Journal of General Internal Medicine; Med Educ = Medical Education; Teach Learn Med = Teaching and Learning in Medicine ª Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2008. MEDICAL EDUCATION 2008; 42: 128–133 131 D A Cook et al DISCUSSION As hypothesised, experimental studies in medical education were mainly conducted for justification or clarification purposes compared with descriptions (84% versus 16%). Furthermore, as in SchmidtÕs study on PBL,18 clarification studies were uncommon: only 12% of the experiments in our sample of studies asked ÔHow?Õ or ÔWhy?Õ questions. If this trend continues, the science of medical education is destined to advance very slowly. To alter this trend, we call for greater use of theoretical or conceptual models or frameworks in the conception and design of medical education studies. While calling for more clarification research, we also acknowledge the continued need for some description studies. There will always be truly innovative ideas and interventions that merit description and dissemination to the education community, laying the groundwork for future innovation and research. Likewise, we anticipate a continued role for justification studies, particularly when looking at higher-order outcomes (behavioural and patient- or practice-oriented outcomes) or when evaluating novel interventions. However, it must be recognised that these studies have a limited impact on our understanding of the teaching and learning process and in turn have limited influence on future practice and research. We are not arguing for the disappearance of description or justification studies, but for a better balance21 among the 3 purposes so that a much larger proportion of research addresses clarification questions. Furthermore, we suggest that description and justification studies should build on previous clarification studies and sound conceptual frameworks. Evaluations of assessment methods were classified as clarification more often than other educational topics, although the sample was small. The reason for this is unclear, but probably reflects a tendency toward explicit conceptual frameworks for experimental research of assessment methods. Although this study focused on experimental research, not all clarification research needs to be experimental. Clarification research can be carried out using non-experimental designs (e.g. correlational studies, comparisons among naturally occurring groups, and qualitative research). This classification of purposes of studies in medical education will be most useful inasmuch as it stimu- 132 lates reflection on existing research and encourages researchers to ask questions that will clarify our understanding. It would be a misuse of the classification if it were the sole criterion by which to grade existing research. Likewise, although we do imply some degree of value judgment attached to research among these purposes, it would be inappropriate to reject a given study solely because it represented description or justification. There will always be a role for such research as long as each piece of research contributes to a growing body of knowledge that advances the science of medical education. This study was limited to experimental studies published in 6 journals in a 2-year period. By requiring the reporting of a dependent variable, we effectively excluded a large number of description studies, which probably explains why we found far fewer description studies than Schmidt found in his analysis of the PBL literature.18 We also cannot comment on the prevalence of study purposes among non-experimental research as this was excluded from our sample. Future reviews, including non-experimental designs and a sample accrued from more journals and ⁄ or a longer period of time, will help draw a more complete picture of the situation. Inter-rater agreement was modest, but final ratings were the result of consensus. Several disagreements occurred in classifying single-group pre-test ⁄ post-test studies as description or justification, and this point is now clarified in our definition of justification research (Table 1). In conclusion, we offer a framework for the classification of the purposes of education research and demonstrate that clarification studies are uncommon in experimental studies in medical education. Although the concepts are not new – indeed, they are as old as the scientific method – we hope that this framework stimulates education scholars to reflect on the purpose of their research and the questions they ask, identify and pursue a sustained line of inquiry (programmatic research), and ask more clarification questions. Such research will deepen our understanding and advance the art and science of medical education. Contributors: DAC and GB planned and executed the study described here. HGS provided the conceptual framework. All authors were involved in the drafting and revising of the manuscript. Acknowledgements: the authors thank T J Beckman, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, for his assistance in the preliminary review process. Funding: none. ª Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2008. MEDICAL EDUCATION 2008; 42: 128–133 Description, justification and clarification Conflicts of interest: GB chairs the international editorial board of Medical Education. We are not aware of other conflicts of interest. Ethical approval: none. 12 13 REFERENCES 1 Harden RM, Grant J, Buckley G, Hart IR. BEME Guide No. 1: best evidence medical education. Med Teach 1999;21:553–62. 2 Dauphinee WD, Wood-Dauphinee S. The need for evidence in medical education: the development of best evidence medical education as an opportunity to inform, guide, and sustain medical education research. Acad Med 2004;79:925–30. 3 Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach 2005;27:10–28. 4 Cook DA. The research we still are not doing: an agenda for the study of computer-based learning. Acad Med 2005;80:541–8. 5 Norman GR. Research in medical education: three decades of progress. BMJ 2002;324:1560–2. 6 Norman G. RCT = results confounded and trivial: the perils of grand educational experiments. Med Educ 2003;37:582–4. 7 Bligh J, Parsell G. Research in medical education: finding its place. Med Educ 1999;33:162–3. 8 Prideaux D, Bligh J. Research in medical education: asking the right questions. Med Educ 2002;36:1114–5. 9 Dolmans D. The effectiveness of PBL: the debate continues. Some concerns about the BEME movement. Med Educ 2003;37:1129–30. 10 Wolf FM, Shea JA, Albanese MA. Toward setting a research agenda for systematic reviews of evidence of the effects of medical education. Teach Learn Med 2001;13:54–60. 11 Prystowsky JB, Bordage G. An outcomes research perspective on medical education: the predominance of 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 trainee assessment and satisfaction. Med Educ 2001;35:331–6. Shea JA. Mind the gap: some reasons why medical education research is different from health services research. Med Educ 2001;35:319–20. Chen FM, Bauchner H, Burstin H. A call for outcomes research in medical education. Acad Med 2004;79:955– 60. Wolf FM. Methodological quality, evidence, and research in medical education (RIME). Acad Med 2004;79 (10 Suppl):68–9. Hutchinson L. Evaluating and researching the effectiveness of educational interventions. BMJ 1999;318:1267–9. Carney PA, Nierenberg DW, Pipas CF, Brooks WB, Stukel TA, Keller AM. Educational epidemiology: applying population-based design and analytic approaches to study medical education. JAMA 2004;292:1044–50. Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Bordage G. Quality of reporting of experimental studies in medical education: a systematic review. Med Educ 2007;41:737–45. Schmidt HG. Influence of research on practices in medical education: the case of problem-based learning. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Medical Education in Europe, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, September 2005. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159– 74. Albert M, Hodges B, Regehr G. Research in medical education: balancing service and science. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2007;12:103–15. Received 13 February 2007; editorial comments to authors 2 July 2007; accepted for publication 15 October 2007 ª Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2008. MEDICAL EDUCATION 2008; 42: 128–133 133