Lecture 1

advertisement

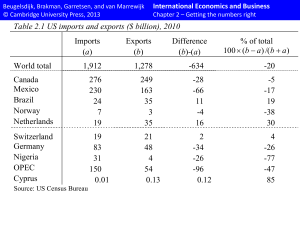

Lecture 1 Page 1 Course Outline and Timetable International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Textbook International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Course Outline and Timetable International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller On-line resources International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Overview: The World Economy • Using exchange rates to compare income levels in different countries underestimates income in developing countries; it is better to use Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) rates to correct for price differences. • We can distinguish two waves of globalization, both for trade flows and capital flows. International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Developing country income higher at PPP rates GDP top 15; ranked according to PPP, 2003 (current $, billions) 10,978 United States 6,410 China 3,062 India 2,279 Germ any France 1,652 Un. Kingdom 1,643 India # 12 at exchange rate; India # 4 at PPP rates 1,546 Italy Brazil 1,326 Rus s ia 1,284 Canada 950 Mexico 919 Spain 910 South Korea 862 current $ current $, PPP 689 Indones ia 0 International Economics China # 7 at exchange rate; China # 2 at PPP rates 3,629 Japan 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000 12,000 © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller 8 Shares of global GDP 1900-2000 35% China % S ha re o f G lo b a l O ut p u t 30% US India 25% 20% 15% Russia UK 10% Japan 5% 0% 1500 China US 1600 India 1700 Japan Time Russia Source: GSChina Global ECS Research India 1800 UK US UK 1900 Japan 2000 Russia Sources: Maddison, 2000, Goldman Sachs, 2003, Revi, 2005 International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller 9 Shares of global GDP 1900-2050 35% China % S ha re o f G lo b a l O ut p u t 30% US India 25% 20% 15% Russia UK 10% Japan 5% 0% 1500 1600 US 1700 Time Source: GSChina Global ECS Research India 1800 1900 UK Japan 2000 Russia Sources: Maddison, 2000, Goldman Sachs, 2003, Revi, 2005 International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller 10 Shares of global GDP 1500-2050 35% China % S ha re o f G lo b a l O ut p u t 30% US India 25% 20% 15% Russia UK 10% Japan 5% 0% 1500 1600 US 1700 Time Source: GSChina Global ECS Research India 1800 1900 UK Japan 2000 Russia Sources: Maddison, 2000, Goldman Sachs, 2003, Revi, 2005 International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller World per capita income increased past 200 years World GDP per capita (1990 international $), logarithmic scale 10,000 5,709 1,000 667 435 444 100 0 International Economics 500 1000 1500 1820 2000 © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Two waves of globalization in trade Merchandise exports, % of GDP in 1990 prices 17.2 15 After World War II 10 13.4 10.1 Before World War I 5 4.6 2.5 0.2 0 1870 1900 1930 world International Economics 1960 USA 1990 Japan © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Merchandise trade typically grows faster than GDP 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6 -8 -10 -12 -14 1950-60 1960-70 1970-80 1980-90 1990-00 2000-09 2001 2002 Exports International Economics 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 GDP © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Two waves of globalization in capital flows Foreign capital stocks; assets / world GDP 0.6 After World War I 0.4 Before World War I 0.2 0 1860 International Economics 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Two waves of globalization • Two waves of globalization: – 1840–1914 – 1980–present • Same underlying factors: – Technological change – Liberalization • The death of distance? Is the world flat? International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Merchandise trade (exports + imports)/2, 2008 Shares in world trade of top 15 traders United States European Union 10,6 Including intra-EU trade Germany 8,2 China 7,9 Japan trade 17,1 Excluding intra-EU United States 14,1 China 4,8 10,4 Japan 6,3 France 4,0 Canada 3,6 Netherlands 3,7 Korea, Republic of 3,5 Italy 3,4 Hong Kong, China 3,1 United Kingdom 3,4 Singapore 2,7 2,5 Belgium 2,9 Mexico Canada 2,7 Taipei, Chinese 2,0 Korea, Republic of 2,6 India 1,9 Hong Kong, China 2,3 Saudi Arabia 1,7 Spain 2,1 United Arab Emirates 1,6 Singapore 2,0 Australia 1,6 Mexico 1,9 Switzerland 1,6 Other Members 32,3 0 International Economics 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 Other Members 19,3 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Exports of top five economies ($bill) 1.600 1.400 1.200 1.000 800 600 400 200 0 China Germany 2000 International Economics Japan 2005 2007 UK US 2008 © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Changing Composition of Trade • What kinds of products do nations currently trade, and how does this composition compare to trade in the past? • Today, most of the value of trade is in manufactured products such as automobiles, computers, clothing and machinery. – Services such as shipping, insurance, legal fees and spending by tourists account for 20% of the volume of trade. – Mineral products (e.g., petroleum, coal, copper) and agricultural products are a relatively small part of trade, in value but not in volume. International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Changing Composition of Trade (cont.) International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Changing Composition of Trade (cont.) • In the past, a large fraction of the volume of trade came from agricultural and mineral products. – In 1910, Britain mainly imported agricultural and mineral products, although manufactured products still represented most of the volume of exports. – In 1910, the US mainly imported and exported agricultural products and mineral products. – In 2002, manufactured products made up most of the volume of imports and exports for both countries. International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Changing Composition of Trade (cont.) • Developing countries, or low and middle-income countries, have also changed the composition of their trade. – In 1960, about 58% of exports from developing countries were agricultural products and only 12% of exports were manufactured products. – In 2001, about 65% of exports from developing countries were manufactured products, and only 10% of exports were agricultural products. International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Multinational Corporations and Outsourcing • Before 1945, multinational corporations played a small role world trade. • But today about one third of all US exports and 42% of all US imports are sales from one division of a multinational corporation to another (there is no comparable EU data) International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Multinational Corporations and Outsourcing • Outsourcing occurs when a firm moves business operations out of the domestic country. – The operations could be run by a subsidiary of a multinational corporation. – Or they could be subcontracted to a foreign firm. • Outsourcing of either type increases the amount of trade. International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Example of global outsourcing: Volvo International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller The Balance of Payments • The BoP is divided in the current account and capital/financial account. • The transactions on the current account are income related. Income gains are recorded as credit items (+) and income spending as debit items (-). • The transactions on the capital/financial account are asset related. Asset gains are recorded as debit (-) and asset losses as credit (+). International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller The items of the Balance of Payments The balance of payments BoP of a country can be subdivided further. Current account Goods Trade balance Services Income Current transfers Capital and financial account Capital account Financial account Direct investment Portfolio investment Other investment Reserve assets International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Accounting identities • By definition the BoP is equal to zero: current account balance + capital/financial account balance = 0 • From this it can be derived that net exports (surplus on the current account) have to be accompanied by a capital outflow (deficit on the capital account). Net imports on the other hand go together with a capital outflow. surplus account balance ⇔ net capital/financial outflow International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Benefits of international capital flows • The benefits of international capital mobility can be illustrated with a relatively simple framework. • Total saving in a country is a positive function of the interest rate and total investment a negative function. • Without capital mobility, the interest rate in two countries can be different as illustrated on the next slide. • The introduction of international capital mobility makes both countries better off. Savings from the country with the lower interest rate will flow to investment opportunities in the other country until the interest rate in both countries equalizes. The next slide shows that both countries are better off. International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Both countries gain from capital mobility net gain = net gain = r r IH SH IF SF rH0 1 rH1 3a 3b 4a rF1 rF0 7.1a International Economics SH1 SH0=IH0 IH1 S, I 4b 2 7.1b IF1 SF0=IF0 SF1 S, I © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller Direction of capital flows • We would expect capital to flow “down-hill”, from capital-rich to capital-poor countries. • This is what we observe within the EU • But at global level things are little more complicated International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller But global (CA) imbalances can be problematic Page 31 International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller The US-China trade balance International Economics © Van Marrewijk, Ottens, Schueller