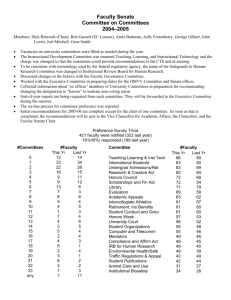

Systems of parliamentary Committees and forms of government

advertisement