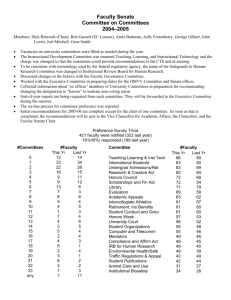

Evolution and Change in Committees

advertisement