- D-Scholarship@Pitt

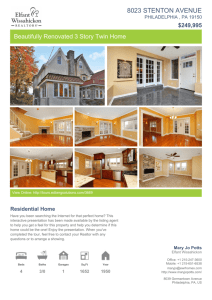

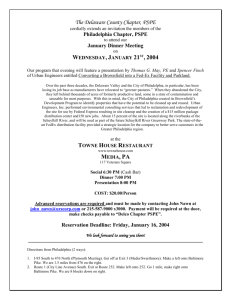

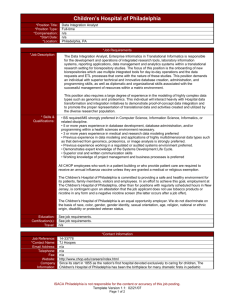

advertisement