Out Online: Trans Self-‐Representation and Community Building on

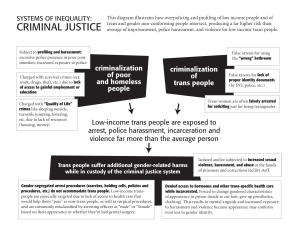

advertisement