THE CASE OF BALTIMORE Deindustrialization Creates 'Death Zones'

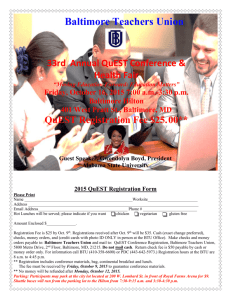

advertisement