The Notions of Literal and Non-literal Meaning in Semantics and

advertisement

The Notions of Literal and Non-literal

Meaning in Semantics and Pragmatics

Dissertation

zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades

doctor philosophiae

(Dr. phil)

Eingereicht an der

Philologischen Fakultät

der Universität Leipzig

von

Kristin Börjesson

Verleihungsbeschluss 10. Oktober 2011

Gutachter:

PD Dr. Johannes Dölling

Institut für Linguistik, Universität Leipzig

Prof. em. Dr. Anita Steube

Institut für Linguistik, Universität Leipzig

Prof. Robyn Carston, PhD

Research Department of Linguistics, University College London

ii

Contents

1 Introduction

1.1 Standard Notions . . . . . . . . . . .

1.2 Are the Standard Notions Adequate?

1.3 Interpretation and Levels of Meaning

1.4 Aims of the Thesis . . . . . . . . . .

1.5 Thesis Plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

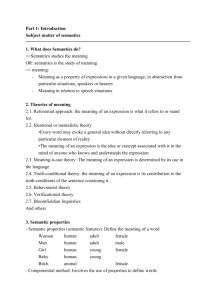

2 Against the Standard Notions of Literal Meaning and Non-literal

Meaning

2.1 Literal Meaning and Context-Independence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.1.1 Literal Meaning as Compositional Meaning? . . . . . . . . . .

2.1.2 Literal Meaning as Context-Independent? . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.1.3 Literal Meaning as Primary to Non-literal Meaning? . . . . . .

2.2 Non-literal Meaning and Conventionality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2.1 Empirical Evidence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2.2 Theoretical Considerations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.3 Consequences for Lexical Meaning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.3.1 Problematic Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.3.2 Approaches to Meaning in the Lexicon . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.3.3 Semantic Underspecification in the Lexicon . . . . . . . . . . .

2.4 Empirical Investigations of Aspects of Semantics . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.4.1 Polysemy vs. Underspecification in the Lexicon . . . . . . . .

2.4.2 Empirical Evidence for Semantic vs. Pragmatic Processing . .

2.5 Why the Standard Notions? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.6 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3 Utterance Meaning and the Literal/Non-literal Distinction

3.1 Levels of Meaning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

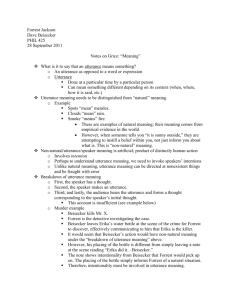

3.1.1 Grice’s Four Types of Meaning . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.1.2 Bierwisch’s Three Levels of Meaning . . . . . . . . . . .

3.1.3 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.2 The Problem of Characterising the Level of Utterance Meaning

3.2.1 Explicit/Implicit Meaning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.2.2 Unarticulated Constituents vs. Hidden Indexicals . . . .

3.2.3 Minimal Semantic Content and Full Propositionality . .

3.2.4 Minimal Proposition vs. Proposition Expressed . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

1

1

3

5

6

6

9

9

10

14

19

23

23

29

35

36

41

51

67

67

71

75

78

83

84

84

88

92

94

95

106

115

123

iv

Contents

3.3

Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

4 Utterance Meaning and Communicative Sense – Two Levels or

One?

133

4.1 Problematic Phenomena . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

4.1.1 Metaphor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

4.1.2 Irony . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

4.1.3 Conversational Implicatures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

4.1.4 Speech Acts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 180

4.2 Differentiating What is Said from What is Meant . . . . . . . . . . . 184

4.2.1 What is Said/What is Meant and Indirect Speech Reports . . 186

4.2.2 Primary vs. Secondary Pragmatic Processes . . . . . . . . . . 189

4.2.3 What is Said/What is Meant and Distinct Knowledge Systems 194

4.3 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200

5 Varieties of Meaning, Context and the Semantics/Pragmatics Distinction

203

5.1 Towards an Alternative Characterisation of (Non-)Literal Meaning . . 203

5.1.1 Literal Meaning and Types of Non-literal Meaning . . . . . . . 205

5.1.2 Literal Meaning as ‘Minimal Meaning’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211

5.1.3 Nature of the Processes Determining (Non)-Literal Meaning . 215

5.1.4 (Non-)Literal Meaning as (Non-)Basic Meaning . . . . . . . . 221

5.2 The Nature of Context in Utterance Interpretation . . . . . . . . . . 227

5.2.1 Context and the Interpretation of Implicit Meaning Aspects . 228

5.2.2 Context, Semantic Interpretation and the Semantics/ Pragmatics Distinction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

5.3 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251

6 Summary

255

Bibliography

259

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1

Standard Notions

One of the major issues in investigating the relation of language and meaning is the

question of how to characterise and draw the line between what traditionally are

called semantics and pragmatics. In describing what they take to be the characteristics of one or the other system, linguists often make use of the terms literal meaning

and non-literal meaning. For example, Lyons (1987) lists a number of propositions

used in the differentiation of semantics from pragmatics, amongst which is the following: ‘. . . that semantics deals with literal, and pragmatics with non-literal, meaning

. . .’ (ibid., p. 157). Similarly, Cole (1981, p. xi) states that semantics ‘. . . is involved

in the determination of conventional (or literal) meaning . . . ’, whereas pragmatics

is concerned with ‘. . . the determination of nonconventional (or nonliteral) meaning

. . . ’ and Kadmon (2001, p. 3) writes ‘. . . I think that roughly, semantics only covers

“literal meaning.” Pragmatics has to do with language use, and with “going beyond

the literal meaning.”’. More recently, Recanati (2004) summarised (and criticised)

the standard view on the division of labour between semantics and pragmatics,

starting with the following sentence.

‘Semantics deals with the literal meaning of words and sentences as determined by the rules of the language, while pragmatics deals with what

the users of the language mean by their utterances of words and sentences.’ (Recanati 2004, p. 3).

Actually, the pair of terms literal meaning/non-literal meaning is only one of

quite a number of dichotomies used in the characterisation of semantics and pragmatics. Thus, the two systems are often characterised in terms of the differentiation

between conventional vs. non-conventional meaning, as, e.g. in the quote from Cole

(1981) above. Similarly, in Lyons (1987) one finds the proposition ‘. . . that semantics has to do with conventional, and pragmatics with the non-conventional,

aspects of meaning . . .’ (ibid., p. 157). Another important pair of terms traditionally used is context-independent vs. context-dependent meaning. Thus, Lyons (1987,

p. 157) states ‘. . . that semantics deals with context-independent, and pragmatics

with context-dependent, meaning’. More specifically, Katz (1977) introduces the notion of the ‘anonymous letter situation’ to characterise the kind of meaning captured

2

Introduction

by semantics.

‘[I] draw the theoretical line between semantic interpretation and pragmatic interpretation by taking the semantic component to properly represent only those aspects of the meaning of the sentence that an ideal

speaker-hearer of the language would know in an anonymous letter situation, . . . [where there is] no clue whatever about the motive, circumstances of transmission, or any other factor relevant to understanding

the sentence on the basis of its context of utterance.’ (Ibid., p. 14)

To summarise, whereas semantics is characterised as dealing with literal, conventional and context-independent meaning, pragmatics deals with non-literal, nonconventional and context-dependent meaning. More generally, the standard notions

of semantics and pragmatics may be described as follows. Semantics deals with

those aspects of meaning that both simple and complex expressions have, independent of their use. In contrast, pragmatics deals with those aspects of meaning that

are determined by the actual use of language.1 That is, semantics is concerned with

meaning that is independent of any specific context, whereas pragmatics specifically

draws on contextual information for the interpretation of some expression.

Assuming that the borderline between semantics and pragmatics is fixed and stable, using the dichotomies mentioned above in the characterisation of the respective

systems suggests that there is a correspondence between literal, conventional and

context-independent meaning, on the one hand, and non-literal, non-conventional

and context-dependent meaning on the other.2 However, one usually does not find

actual characterisations of the kind of meaning picked out by the terms literal meaning and non-literal meaning other than such that again (more or less explicitly) relate

the two notions back to the semantics/pragmatics distinction. For instance, Bach

(2001a) writes

‘Words do not have nonliteral meanings [. . . ], but they can be used in

nonliteral ways. [. . . ] In familiar cases, such as metaphor and metonymy,

particular expressions are used nonliterally. [. . . ] But there is a different

phenomenon which I call “sentence nonliterality,” [. . . ] Here a whole

sentence is used nonliterally, without any of its constituent expressions

being so used.’(Ibid., p. 249, my emphasis).

Thus, whereas literal meaning is a feature that expressions are said to have, the nonliteral meaning of an expression results from the particular use of that expression.

Moreover, not only simple but also complex expressions can be used non-literally. In

both cases, the non-literal meaning results from the actual use of a certain expression

in a specific context. In addition to the circumscription ‘non-literal use of language’,

one finds descriptions such as ‘non-literal utterances’ (cf. Carston 2005) or ‘nonliteral interpretation’ (cf. Papafragou 1996, Ariel 2002, Carston 2005).

1

Cp., again, Lyons (1987) who mentions the idea that ‘. . . semantics has to do with meaning,

and pragmatics with use . . .’ (Ibid., p. 157).

2

From the quotes given above, this is especially apparent in Cole’s, who uses the terms literal

and non-literal as synonymous to conventional and non-conventional, respectively.

Are the Standard Notions Adequate?

3

Generally, it seems that the two terms literal meaning and non-literal meaning

are treated as denoting basic kinds of meaning that are intuitively clear and as such

need no further description. However, although there are no clear definitions of the

terms literal meaning and non-literal meaning given in the literature concerned, the

fact that the two terms are used amongst others in a dichotomous characterisation

of semantics and pragmatics suggests that these terms may also be used in characterising literal meaning and non-literal meaning as such (or the other way around

as done by Cole). This latter characterisation has led to what might be called the

standard notions of literal meaning and non-literal meaning which are summarised

in what follows.

Literal meaning, on the one hand, is assumed to be conventionalised, that is, it

does not take any special interpretation effort to arrive at it. The literal meaning

of simple expressions is listed in their lexical entries; the literal meaning of complex

expressions is the result of a principled combination of the literal meanings of their

parts. Thus, both the literal meaning of simple as well as complex expressions is

characterised by the fact that it is context-independent. Non-literal meaning, on

the other hand, is assumed to be non-conventionalised, thus, it does take a special

interpretation effort to arrive at it. Intuitively, it is considered as deviating from

some more basic (literal) meaning in a fairly special way. Overall, the term nonliteral meaning is used to differentiate from literal meaning a kind of meaning that

is derived from the latter and, in a sense, has a secondary status. Therefore, it is

traditionally assumed that in terms of the enfolding of the interpretation process,

the literal meaning of an expression is processed first, whereas any potential nonliteral meanings are processed afterwards and only if the literal interpretation does

not fit the given context.

Finally, in accordance with the standard characterisations of semantics and pragmatics given above, literal meaning is traditionally assumed to belong to the domain

of semantics (as it can apparently be determined without reference to any particular

context of utterance), whereas non-literal meaning is assumed to be properly investigated by pragmatics (as it seems it can only be determined by taking into account

the context of an utterance). Such a classification presumes that the definitions of

the terms literal meaning and non-literal meaning, as well as the characterisation

of what semantics and pragmatics are concerned with are indisputably clear. However, the ongoing debate about the proper demarcation of semantics from pragmatics

show that this is not at all the case (Carston 1999, Levinson 2000, Bezuidenhout and

Cutting 2002, Bianchi 2004, Carston 2004a, Recanati 2004, Cappelen and Lepore

2005, Dölling 2005, Carston 2007, etc.).

1.2

Are the Standard Notions Adequate?

Note that although there is something like a standard characterisation for the terms

literal meaning and non-literal meaning, they are not consistently used in accord

with these characterisations. For instance, the term literal meaning is not only used

in connection with such phenomena as are considered totally context-independent.

Thus, Carston (2007) refers to the ‘. . . literal meaning of [a speaker’s] utterance’

(ibid., p. 21). Similarly, Recanati (1995) speaks of ‘. . . the literal interpretation of

4

Introduction

an utterance (the proposition literally expressed by that utterance). . . ’ (ibid, p.

2) and Sag (1981) speaks of the ‘. . . propositional content of an utterance (i.e., its

literal meaning) . . . ’ (ibid, p. 274-5). What makes such descriptions interesting

in the present context is that what the authors refer to by the description ‘literal

meaning of an utterance’ does not necessarily correspond to the context-independent

meaning of the expression used to make the particular utterance, since, as we will

see, this need not actually be a full proposition. Rather, they use the term literal

here to differentiate the meaning of some expression in a particular context from

the meaning that the speaker actually intended to express (or at least is taken by

the hearer to have expressed). Bezuidenhout and Cutting (2002, p. 435) make a

similar observation when they say that ‘[t]he phrases “literal meaning” or “literal

interpretation” have been used to cover both the literal meaning of a sentence and

what is said by the utterance of a sentence in a context.’ This is also noted by Korta

and Perry (2008), who write that ‘[w]hat is said has been widely identified with the

literal content of the utterance . . .’. Generally, the term literal meaning is used with

respect to a level of meaning which can no longer be said to be context-independent.

It should be noted that it is authors who reject the standard characterisation of

semantics and pragmatics that use the terms literal meaning and non-literal meaning

in a non-standard understanding. The problem is that they do so implicitly. That

is, these authors do not explicitly say anything new concerning the understanding

of the terms literal meaning and non-literal meaning. As Wilson and Sperber (2000,

p. 250) put it, ‘[t]he notion of literal meaning, which plays such a central role in

most theories of language use, is unclear in many respects’. Note also that it is

not only the pair of terms literal (meaning)/non-literal (meaning) that is employed

differently in the various approaches. Such notions as (non)-conventionality and

context-(in)dependence are problematic as well. Thus, the use of the pair of terms

conventional vs. non-conventional as exemplified above suggests that conventionality is an all-or-nothing property. However, as is suggested by the results of various

experiments investigating the nature of the interpretation process on the one hand

(cf. Giora 1997, 1999, Gibbs 2002), as well as theoretical considerations within the

field of historical semantics on the other (cf. Busse 1991), this view is an oversimplification of the facts. Similarly, not all approaches that are characterised as essentially

semantic by their proponents necessarily share the view that what semantics deals

with is context-independent meaning only (cf. Sag 1981, Borg 2004b, Cappelen and

Lepore 2005).

The problem that arises is that if the terms in which the notions literal meaning

and non-literal meaning are defined are put under closer scrutiny, it might turn out

that they do not capture the aspects that we intuitively and pre-theoretically associate with the notions of literal meaning and non-literal meaning. Another problem

is that with only the standard notions of literal meaning and non-literal meaning to

rely on, it is no trivial question to ask how these two meaning aspects are related to

other kinds of meaning aspects identified in the individual approaches, such as e.g.,

explicit/implicit meaning aspects of an utterance, so-called ad-hoc concepts or conversational implicatures. For instance, metaphor – one particular type of non-literal

meaning – has actually been treated in terms of conversational implicature and so

has irony. In fact, conversational implicatures in general have been characterised as

Interpretation and Levels of Meaning

5

non-literal (cf. Recanati 2004), although, intuitively at least – and especially if one

actually does not count metaphor and irony amongst them – this is a questionable

claim.

1.3

Interpretation and Levels of Meaning

A further point to note is that the assumption that two systems, namely semantics

and pragmatics, are involved in the interpretation of natural language utterances

suggests that there is also only a differentiation of two levels of meaning necessary.

Thus, the semantic component takes the lexical meanings of the individual expressions used in an utterance and combines them in a principled manner, resulting

in the truth-conditional or semantic meaning of the complex expression used in an

utterance, traditionally taken to be a proposition. This semantic meaning, then,

is the input to the pragmatic component which determines what the speaker who

uttered the expression in question actually meant in a particular situation. This is

the view usually taken to underlie Grice’s differentiation of the two levels of meaning what is said and what is meant.3 In Grice’s terminology then, literal meaning

is part of the level of what is said, whereas non-literal meaning is to be found only

at the level of what is meant. However, it has been pointed out both in Neo- as

well as Post-Gricean approaches that Grice’s notion of what is said is problematic.

More specifically, it has been argued that what is said cannot both be the semantic

meaning of an utterance as well as the basis for drawing conversational implicatures

(cf. Sperber and Wilson 1995, Levinson 2000, Carston 2002c, Recanati 2004).

As a consequence of such problems of Grice’s approach, more than two levels

of meaning have been assumed: a level that captures the semantic meaning of an

expression, a context-dependent level that can function as the basis for further

pragmatic inferences to be drawn (call this what is said for now) and the level of

what is meant. What is interesting to note with respect to the differentiation of three

levels of meaning is the various possibilities this opens up for the classification of

literal meaning and non-literal meaning. Thus, with the differentiation of semantic

meaning from what is said, the question arises where ‘to put’ literal meaning: is

it part of the level of semantic meaning or part of the level of what is said? The

quotations above suggest that different linguists hold different views concerning this

question. Note also that a similar question can be asked concerning non-literal

meaning. That is, with the differentiation of the two distinct levels of contextsensitive meaning what is said and what is meant, the question arises whether nonliteral meaning aspects exclusively belong to the latter level or whether they might

not already arise at the former. Note that if both literal meaning and non-literal

meaning are assumed to arise at the level of what is said already, then this would

suggest that the two types of meaning are not as different from one another as

traditionally assumed.

However, the various approaches to the interpretation of natural language differ

in the characterisations they assume for the individual levels of meaning identified.

3

It should be noted that in his efforts to explicate the notions of saying vs. meaning, Grice

actually contemplated four different types of meaning. For more on this issue see chapter 3.

6

Introduction

Again, the different characterisations are dependent on the particular views held

regarding the nature of the semantic and pragmatic components, the roles they play

in the overall interpretation process as well as the type of information they are

assumed to have access to.

1.4

Aims of the Thesis

I want to show that the standard notions of literal meaning and non-literal meaning

are not consistent and that, as a result, the two terms cannot be used to differentiate

between the types of meaning aspects semantics and pragmatics are usually assumed

to deal with. In contrast, I want to develop a characterisation of literal meaning and

non-literal meaning that is consistent and captures the various uses the two terms

are put to. In addition, I want to defend the view that differentiating between two

context-dependent levels of meaning what is said/utterance meaning and what is

meant/communicative sense is possible and necessary. In particular, I will propose

a modelling of the process that provides implicit meaning aspects to the level of

what is said/utterance meaning that allows viewing this process – as the processes

contributing to this level of meaning in general – as operating independently of

considerations of speaker intentions. Finally, I want to show that a differentiation

of semantics from pragmatics that implicitly relies on a logical or temporal ordering

of the two systems is inappropriate. Rather, the processes constituting these two

systems should be seen as operating in tandem.

1.5

Thesis Plan

The thesis is structured as follows. In chapter 2, I will argue against the standard notions of literal meaning and non-literal meaning. In particular, I will argue

against the traditional characterisation of literal meaning and non-literal meaning,

according to which the former is taken to be context-independent and the latter

non-conventional. Having established that literal meaning does not necessarily have

to be taken to be context-independent and as such semantic in nature, I will discuss

the consequences this view has for the nature of lexical meaning. After reviewing a

number of different types of approaches to lexical meaning, I will argue for a view

that assumes a high degree of underspecification of lexical meaning. Generally, in

the discussions in chapter 1, I will consider both theoretical viewpoints as well as

empirical data. In particular, one section is dedicated to empirical studies on aspects of the semantics component, namely that lexical meaning is characterised by

underspecification and that, generally, semantic processes of meaning construction

should be differentiated from pragmatically based plausibility checks. In the last

part of chapter 1, I will try to answer the question of why the standard notions of

literal meaning and non-literal meaning came to be assumed in the first place. Here,

the idea of stereotypical interpretations of linguistic expressions presented ‘out of

context’ will be considered.

Having argued against the standard notions in chapter 2, and more specifically,

having argued for viewing literal meaning, similarly to non-literal meaning as essen-

Thesis Plan

7

tially context-dependent as well, chapter 3 is dedicated to looking in detail at the first

context-dependent level of meaning called what is said by Grice, to see how this has

been characterised subsequently and to identify the processes potentially involved

in determining literal meaning at this level of meaning. I will start with Grice’s

differentiation of four different types of meaning and relate them to the two levels

of meaning Grice introduced: what is said and what is meant. Following that, I will

present Bierwisch’s threefold differentiation of levels of meaning, based on the different knowledge systems made use of in their determination. In the second part of

chapter 3, I will discuss a range of approaches that give alternative characterisations

for Grice’s level of what is said. The overall aim is to identify the different processes

at work in determining what is said, how these processes are characterised and which

types of meaning aspects can be found at this level of meaning (appart from potentially literal or non-literal meaning). At the same time, the various approaches

discussed also all offer slightly different views on the nature of the semantics and

pragmatics components and how they interact in the process of utterance interpretation. While the greater part of chapter 3 is taken up by theoretical considerations,

towards the end of that chapter a few empirical results will also be discussed.

Chapter 4, then, is concerned, on the one hand, with phenomena traditionally

assumed to arise at Grice’s level of meaning what is meant, and, on the other hand,

with the more basic question of whether a differentiation of two context-dependent

levels of meaning what is said and what is meant actually is necessary/possible.

Thus, in the first part of chapter 4, alternative approaches to the phenomena of

metaphor, irony, (primarily generalised) conversational implicature and (primarily

indirect) speech acts will be reviewed as well as empirical results considered that

test the predictions following from the individual approaches. Here, the aim is to

establish, on the one hand, how these different meaning aspects are determined and,

on the other hand, which of the phenomena actually can be usefully considered as

non-literal. More generally, the question is addressed at which level of meaning (i.e.

what is said or what is meant) the individual phenomena should be taken to arise.

In the second part of chapter 4, various arguments will be presented for and against

differentiating the two levels what is said and what is meant from one another. I

hope to make clear that such a differentiation is useful and necessary, although it

might be difficult to decide on the criteria to be used in this differentiation.

Chapter 5, finally, turns back to the basic question that chapter 2 ends with,

namely how literal meaning and non-literal meaning actually should be characterised

if one wants to capture the various uses the two terms are put to. I will start out with

two alternative characterisations of what literal meaning and non-literal meaning

should be taken to be, before presenting my own characterisation, based on the

discussion in the preceding chapters. As a preliminary for my characterisation, I

will review the various processes identified in the preceding chapters as involved

in the overall interpretation of utterances. The main consequence drawn from my

characterisation of literal meaning and non-literal meaning will be that these two

notions actually cannot be used in the characterisation of the distinction between

semantics and pragmatics, if the former, in contrast to the latter, is essentially

taken to be context-independent. The last part of chapter 5 will take up exactly this

point, namely the nature of contextual information in utterance interpretation and

8

Introduction

whether the notion of context-(in)dependence actually is useful in differentiating

between semantics and pragmatics. Thus, I will first offer a proposal concerning

the nature of the contextual information the process of free enrichment makes use

of. Free enrichment is one of the processes assumed to contribute to the level of

utterance meaning and crucially is taken to depend on a consideration of potential

speaker intentions for its operation. I will show that this assumption is not necessary.

In the final section of chapter 5, I will turn back to the characterisation of the

semantics/pragmatics distinction and after discussing a number of views on that

characterisation present my own.

Chapter 2

Against the Standard Notions of

Literal Meaning and Non-literal

Meaning

In this chapter, I will argue against the standard notions of literal meaning and

non-literal meaning described in chapter 1 (sections 2.1 and 2.2, respectively). The

main aim of this chapter is to show that the dichotomies traditionally used to differentiate literal meaning from non-literal meaning either cannot in fact differentiate

the two meanings (as is the case with the feature of context-(in)dependence) or are

not such ‘all-or-nothing’ concepts as traditionally implied (as is the case with the

property of conventionality). Generally, the arguments presented point to the crucial

conclusion that literal meaning and non-literal meaning are in fact not so different

from one another as traditionally assumed. Having argued against viewing literal

meaning as essentially context-independent and non-literal meaning as essentially

non-conventional, I will consider the consequences this has for the nature of lexical

meaning (section 2.3). Moreover, I will consider empirical evidence supporting the

assumption of underspecification of lexical meaning and, more generally, a distinction between distinctly semantic and pragmatic processes in interpretation (2.4). In

addition, I will address the question of why the standard assumptions came into

existence in the first place (section 2.5).

2.1

Literal Meaning and Context-Independence

Traditionally, complex expressions are assumed to have literal meaning in the form

of what formal semantics1 calls sentence meaning, which results from the process of

semantic composition which combines the literal meanings of the simple expressions

that together constitute the complex expression and which captures the proposition

expressed by that sentence.2 Moreover, during interpretation, the literal meaning of

1

Note that in what follows, on the semantics side, I am primarily interested in assumptions

made in the programme of formal semantics.

2

In this section, I will primarely be concerned with two of the three properties literal meaning

is standardly claimed to exhibit, namely that it is context-independent and primary to non-literal

meaning. Thus, I will concentrate on complex expressions, leaving the discussion of the nature of

10

Against the Standard Notions of Literal Meaning and Non-literal Meaning

a complex expression is computed first, whereas its potential non-literal meaning is

computed afterwards and only if the literal meaning does not fit the given context

(cf. Grice 1975; Searle 1979).

Intuitively, these characterisations seem to be sound. They give a fairly general

description of what we take to be literal meaning with respect to complex expressions. However, looking at each of the characteristics in more detail reveals that

they are not unproblematic. Thus, it is questionable whether what we usually take

to be a complex expression’s literal meaning does in fact correspond to its contextindependent, compositional meaning. Put differently, the question is whether the

formal semantic notion of sentence meaning can be assumed to both be the sum

of the lexical meanings of the simple expressions involved as well as having a fully

propositional form. Furthermore, in computing the ‘speaker-intended’ non-literal

meaning of an expression, it may not actually be necessary to first compute the

literal meaning of the expression the speaker used as an intermediate step.

2.1.1

Literal Meaning as Compositional Meaning?

Concentrating on the traditional characterisation of the programme of formal semantics and the role of literal meaning therein reveals that, in a sense, the characterisation of literal meaning and non-literal meaning is interdependent on the

characterisations of semantics and pragmatics. Thus, basically, formal semantics

can be characterised as dealing with the context-independent meaning of simple

and complex expressions.3 More specifically, it aims at formulating truth conditions

for sentences. That is, it takes as a starting point for analysis the level of sentence

meaning, mainly for two reasons. First, it seems that sentences express propositions, that is, complete thoughts, something of which it makes sense to ask whether

it is true or not. Second, intuitively at least, the meaning of a sentence can be

grasped without any reference to an actual utterance of that sentence and is thus

context-independent. It contrasts with interpretations of a sentence that can only

be derived by considering the actual context in which that sentence is uttered (e.g.,

cases of irony or particularised conversational implicature). Thus, sentence meaning

is considered literal in the sense that its derivation is independent of contextual information. Moreover, sentence meaning also is the level from which the meanings

of the individual expressions involved are derived, following the principle of compositionality. And since sentence meaning is context-independent, the meanings of

the simple expressions derived from it are context-independent too. They are the

lexical meanings of the expressions concerned. Thus, primarily, what the term literal

meaning refers to is a certain type of meaning that, intuitively, seems to differ from

other types of meaning mainly by virtue of the fact that it is context-independent

and fully propositional (sentence meaning). Derivatively, the term also refers to

types of meaning which are not propositional, but crucially are context-independent

and are derived from a full proposition via the principle of compositionality (lexical

meaning).

lexical meaning to section 2.3.

3

See below, however, for formal semantic approaches that also take into account contextual

information.

Literal Meaning and Context-Independence

11

meaning

context-independent

lexical m. sentence m.

literal

context-dependent

...

...

...

non-literal

Figure 2.1: Traditional differentiation of types of meaning

So far so good. However, the characterisation of formal semantics as stated above

has proven to be problematic. And, as we will see, these problems also extend to the

characterisation given to the notion of literal meaning. Thus, to summarise: in its

traditional form, three of formal semantics’ main assumptions are the following: a)

semantics is concerned with the context-independent meaning of natural language

expressions, b) for sentences, what is determined by the semantic component of a

natural language grammar is the proposition expressed by that sentence and c) for

simple expressions their semantics (or lexical meaning) is whatever aspects of their

meaning remain constant across different uses of that expression.

However, as Sag (1981) points out: a formal semantic theory which does not allow

for any contextual information to be made use of in determining the proposition

expressed by a sentence ‘. . . appears to be falsified by the mere existence of sentences

containing tense morphemes or other indexical expressions.’ (Ibid, p. 274). Thus,

consider the sentence in (1).

(1) He went to the bank yesterday.

For the sentence in example (1), it is clearly not the case, that semantics determines

a truth-evaluable proposition, due to the occurrences of the context-dependent expressions he and yesterday as well as the homonymous noun bank. As is the case

for all indexical expressions, the exact reference of he and yesterday differs with the

contexts in which they are uttered. Thus, for such expressions semantics only gives

rules for ’where to look’ in the search for potential referents. In the case of the occurrence in a sentence of homonymous expressions such as bank, the assumption is that

the process of semantic composition has to build up as many different structures

for the sentence, as there are ambiguous expressions in it. Thus, for (1) to express

a full proposition, the references of the occurring indexical expressions have to be

fixed, that is, recourse has to be taken to the context of the utterance. Moreover,

the sentence has to be disambiguated, which, again, is only possible with the help

of contextual information. Even then, the sentence does not express a proposition

until the reference of the NP the bank to some unique location has been fixed. What

this shows is that the proposition expressed by some sentence can only actually be

12

Against the Standard Notions of Literal Meaning and Non-literal Meaning

determined once the context in which it is uttered is taken into consideration. Thus,

it seems that the semanticist cannot uphold both assumptions a) and b). If he wants

to rescue assumption a), it seems he has to concede that, in fact, the semantic component does not determine the truth-evaluable proposition expressed by a sentence;

if he wants to rescue the assumption in b), he has to allow for context-sensitive

processes to take place during the determination of the proposition expressed by a

sentence.

However, formal semantic approaches exist which attempt to capture the difference between context-sensitive and context-insensitive expressions and at the same

time uphold assumptions a) and b). One such approach is Kaplan (1989b). Thus,

Kaplan proposes to differentiate between, in a sense, two meanings of expressions:

their character and their content.4 Consider example (2).

(2) a. Mary: I am hungry.

b. John: I am hungry.

On the one hand, the notion of character captures the intuition that Mary and John

in a way have said the same thing: both used the same sentence. The notion of

content, on the other hand, captures the intuition that, at the same time, Mary and

John have not expressed the same idea. Kaplan’s suggestion is that a sentence’s

character is a function that takes a context in order to deliver a proposition or the

content of that sentence in that context. Thus, although Mary and John use the same

sentence, they express different propositions: Mary says that she is hungry, whereas

John says that he is hungry. This difference is due to the character of I, which can be

glossed as ‘referring to the speaker or writer’. Applying I’s character to a particular

context determines the actual speaker in that context, i.e., the content (or intension)

of I in that particular context. Having determined the proposition expressed by a

sentence in a particular context, the proposition can then be evaluated with respect

to a circumstance of use or possible world. Thus, the content (or intension) of a

sentence in a particular context is a function from possible worlds to truth values.

In Kaplan’s approach, then, context-sensitive expressions are such that their

character applied to different contexts yields different contents. However, a contextsensitive expression’s content in turn is a constant function from possible worlds to

extensions since regardless of the world at which the content of the expression is

evaluated, it will always have the same extension. For example, the content of an

expression such as I varies depending on the context in which it is used. However,

once the content is determined, it stays the same for all possible worlds. In contrast,

the content of hungry does not depend on the context in which it is used. It always

is the property ‘being-hungry’. However, the actual extension of this predicate

depends on the possible world that is assumed. That is, the set of individuals

to which the predicate applies may differ across different worlds. Thus, contextinsensitive expressions have varying extensions, while their characters are such that

regardless of the context the respective character is applied to, the same content

will be determined. In a way, for context-insensitive expressions their character and

content fall together.

4

Cf. Chierchia and McConnell-Ginet (2000), Braun (2010) for accessible introductions to these

notions.

Literal Meaning and Context-Independence

13

Kaplan’s approach, thus, allows a differentiation of three levels of meaning: character, content or intension and extension. For sentences this means one can differentiate between the context-independent sentence meaning, the proposition expressed

by a sentence in a context and the truth value of a sentence in a context with respect

to a possible world. Thus, implementing these ideas in a model-theoretic semantic

apparatus leads to the truth of a sentence not only being determined with respect

to a world and time, but also a context of utterance (cf. Sag 1981).

In a way, within such an approach, both assumptions a) and b) can be maintained. That is, what is determined by the semantic component is the contextindependent meaning of a sentence and the conditions under which that sentence is

true. Using the indices w, i and c, the instruction of how to determine the proposition expressed by a sentence is also given. However, it should be noted that the

proposition expressed only actually is determined, once the functions are applied to

a particular world, time and context. In other words, although it is possible within

such an approach to formulate conditions under which a particular sentence is true,

due to the indices used the sentence’s meaning thus given may be compatible with

quite a number of different situations. Thus, it cannot be taken to represent the

proposition expressed in a particular utterance situation.

Traditionally, formal semanticists have assumed that the semantic component of

the language faculty determines the meaning both of simple and complex expressions

and then there are a restricted number of processes (namely, resolving of reference,

fixing of indexicals and disambiguation) that lead to the proposition expressed by

a sentence. However, these processes are not explicitly referred to as being of a

pragmatic nature. This is quite obvious in the works of Grice, who mentions the

processes that lead to what he called what is said, but does not seem to consider

them as pragmatic in the same sense as the processes that result in conversational

implicatures (Grice 1975) (cf. figure 2.2). However, if pragmatic processes are characterised by the fact that they take into account contextual information then, surely,

the processes of fixing indexicals, resolving references and disambiguation are of

pragmatic nature.

Semantics lexical meaning

semantic composition

sentence meaning

?

reference resolution

fixing indexicals

disambiguation

what is said

Pragmatics

basis for further

pragmatic inferences

conversational implicature

...

what is meant

Figure 2.2: Grice’s distinction of what is said and what is meant

14

Against the Standard Notions of Literal Meaning and Non-literal Meaning

Thus, as Strawson (1950) noted, it is not sentences which express something of

which it makes sense to ask whether it is true or false but rather the utterances of

those sentences. Thus, one and the same sentence can be used to express something

true at one point and something false at another. That is, regardless of whether

sentences include indexical or ambiguous expressions, it is not a general property of

sentences, but rather of utterances that they express propositions.

If it is not sentences per se that express propositions and are truth-evaluable but

rather their utterances, what exactly, then, does the concept of sentence meaning

capture? This is an important question considering that formal semantics takes

sentence meaning as the starting point from which to deduce the meanings of simple expressions, which presupposes that the notion of sentence meaning is clearly

defined. A possible answer is to still regard both the meaning of simple as well

as complex expressions, in particular sentences, as essentially context-independent.

That is, as traditionally assumed, semantics deals with the meaning of both simple

and complex expressions, where the meaning of simple expressions forms part of

their lexical entries and the meaning of complex expressions is a function of the

meanings of their parts and their syntactic combination. However, such a view does

not claim that sentence meaning necessarily is propositional; it simply assumes that

sentence meaning is context-independent.

2.1.2

Literal Meaning as Context-Independent?

But what about the correlation between sentence meaning and literal meaning suggested above? There it was stated that, apparently, literal meaning refers to a level

of meaning identified as sentence meaning by traditional formal semantics and characterised as being context-independent and fully propositional. The assumption was

that the notion of literal meaning mainly captures the fact that sentence meaning is

context-independent, thus, with the revised characterisation of sentence meaning as

‘only’ context-independent but not necessarily fully propositional, the term literal

meaning should still be applicable to that level of meaning.

There are a number of considerations that go against this characterisation. Thus,

recall the uses of the term literal meaning mentioned in chapter 1, where the term,

on the one hand, is used to refer to a kind of context-dependent but at the same

time in some sense ‘basic’ meaning and, on the other hand, is contrasted with a kind

of meaning that is not only context-dependent but crucially in some sense ‘derived’

or non-basic (cf. Sag 1981, Recanati 1995, Carston 2007). As mentioned before,

such a use calls into question the adequacy of characterising literal meaning as

context-independent meaning. In fact, already in his (1978) paper, Searle criticised

this characterisation of literal meaning. He argues that there is no such thing as a

solely linguistically determined literal meaning of a complex expression. As regards

sentence meaning, one cannot speak of the literal meaning of a sentence in the

standard sense. As Recanati (2004) puts it, Searle holds the view of contextualism,

according to which ‘. . . there is no level of meaning which is both (i) propositional

(truth-evaluable) and (ii) minimalist, that is, unaffected by top-down factors.’ (Ibid.,

p. 90). Thus, Searle assumes that the expression of a determinate proposition takes

place against a set of background assumptions. To illustrate his point of view, Searle

Literal Meaning and Context-Independence

15

uses the sentence in (3), which, taken out of context, seems to have a quite obvious

literal meaning, which Searle (1978) depicts as in 2.3.

(3) The cat is on the mat.

Figure 2.3: The typical cat-on-the-mat configuration

The problem with this ‘literal sentence meaning’ is that although speakers or

hearers are not necessarily aware of the fact, a number of preconditions are assumed

to hold5 . To show this, Searle constructs a context of utterance for the sentence

in (3), where it is questionable whether one would want to say that the sentence

correctly describes the state of affairs at hand.

‘. . . suppose the cat and the mat are in exactly the relations depicted only

they are floating freely in outer space, perhaps the Milky Way galaxy

altogether. In such a situation the scene would be just as well depicted if

we turn the paper on edge or upside down since there is no gravitational

field relative to which one is above the other. Is the cat still on the mat?’

(Searle 1978, cited from Searle 1979, p. 122)

Thus, if what the meaning of a sentence does is determine a set of truth-conditions,

Searle argues that for most sentences this determination can only take place against

specific background assumptions. These background assumptions are not part of

the semantic structure of the sentence, that is, they are unarticulated. Moreover,

due to possible variations in the background assumptions, the same sentence might

have varying truth-conditions. For any sentence, there is no fixed set of background

assumptions of which it could be said that it determines that sentence’s literal

meaning. To illustrate this fact, Searle construes a context of utterance for (3), in

which it could be used to truthfully describe a situation such as depicted in figure

2.46 .

A further example for the fact that the literal meaning of a sentence depends on

background assumptions can be found in Searle (1980). Searle gives a number of

sentences containing the verb to cut; here are the first five.

5

Note that Searle is not referring to the fact that the sentence in (3) additionally contains

indexical elements. That is another matter.

6

This is Searle’s context: ‘The mat is in its stiff angled position, as in [figure 2.4], and it is part

of a row of objects similarly sticking up at odd angles - a board, a fence post, an iron rod, etc.

These facts are known to both speaker and hearer. The cat jumps from one of these objects to

another. It is pretty obvious what the correct answer to the question “Where is the cat?” should

be when the cat is in the attitude depicted in [figure 2.4]: The cat is on the mat.’ (Searle 1978,

cited from Searle 1979, p. 125).

16

Against the Standard Notions of Literal Meaning and Non-literal Meaning

Figure 2.4: A rather unusual cat-on-the-mat configuration

(4) a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

Bill cut the grass.

The barber cut Tom’s hair.

Sally cut the cake.

I just cut my skin.

The tailor cut the cloth.

As Searle notes, in each of the example sentences in (4) cut occurs in its literal

meaning. There is nothing in these sentences as such that would lead one to interpret

them as metaphorical or figurative. However, although cut occurs in its literal

meaning, the situations that it is used to describe differ conceptually. Thus, although

cut is used in its literal meaning, for the different sentences in (4), it determines

different truth conditions. This can be seen if one considers what it would mean to

obey an order of cutting something. Searle puts it as follows.

If someone tells me to cut the grass and I rush out and stab it with

a knife, or if I am ordered to cut the cake and I run over it with a

lawnmower, in each case I will have failed to obey the order. That is

not what the speaker meant by his literal and serious utterance of the

sentence. (Searle 1980, p. 223).

Thus, again, in the examples in (4), the literal meaning of the individual sentences

(and of the word cut) is determined against a set of background assumptions, namely

what we know about lawns and cakes and so on and what are usual actions in which

we involve with regard to those ‘things’.

Furthermore, in his discussion on the cut examples, Searle points out that it is

not sufficient to assume that the different readings of cut – its different literal meanings are due to some intrasentential interaction between the verb and its internal

argument. That is, he argues against the view according to which cut together with

the respective argument determines that cut in ‘cut the grass’ will receive a different

interpretation from the one it receives in ‘cut the cake’. His reasoning is that it is

possible to ‘. . . imagine circumstances in which “cut” in “cut the grass” would have

the same interpretation it has in “cut the cake”. . . ’ (Searle 1980, p. 224).

‘Suppose you and I run a sod farm where we sell strips of grass turf to

people who want a lawn in a hurry. [. . . ] Suppose I say to you, “Cut half

an acre of grass for this customer”; I might mean not that you should

mow it, but that you should slice it into strips as you could cut a cake

or a loaf of bread.’ (Searle 1980, p. 224–5).

Literal Meaning and Context-Independence

17

Moreover, he points out that there is a difference to be drawn between what he

calls background assumptions and the special context of utterance for a given utterance. While background assumptions are involved in determining a sentence’s literal

meaning or truth-conditions, the context in which a sentence is uttered helps the

hearer to decide on whether a speaker intended her utterance to be taken literally

or non-literally. However, since Searle does not explicitly define what constitutes

background assumptions and what is part of the context of an utterance, the question arises whether this differentiation really is necessary. From the examples Searle

uses to defend his view of what constitutes literal meaning, it could be argued that

the background assumptions necessary for determining the literal meaning of a sentence are in fact part of the specific context in which an utterance takes place. What

Searle obviously means by background assumptions are certain aspects of knowledge

that we have, namely those aspects which are relevant in the particular utterance

situation. Thus, one could also assume that depending on the situation speakers

and hearers find themselves in that situation will make certain aspects of knowledge

they have more prominent (or salient). Those aspects, then, constitute what Searle

calls background assumptions in the sense that speakers and hearers are presumably

normally not aware of basing their utterances and interpretations on such assumptions. As their name implies, background assumptions are in the background; they

form the basis from which speakers formulate their utterances and hearers intepret

them. Thus, background assumptions depend on the particular context of utterance

and therefore can be said to form part of the contextual information used in interpreting. Thus, in order to disambiguate whether the expression cut is used with the

meaning as in ‘cut the grass’ or with the meaning as in ‘cut the cake’, the hearer

needs to take into account contextual information. That is, even if the background

of the utterance is such as Searle gives it, the hearer would still have to decide that

the reading of cut as in ‘cut the cake’ is the one the speaker intended in that situation. From what has been said about salience of meaning above, it is of course very

likely that the particular utterance situation will speed up the hearer’s unconscious

decision.

Furthermore, Searle’s argument that there are possible circumstances in which

cut in ‘cut the grass’ may be interpreted as in ‘cut the cake’ actually does not constitute an argument against the assumption that the interpretation of cut is influenced

by the intrasentential context. That is, one could assume that the co-occurrence of

particular lexical items does help the hearer to narrow down the possible sentence

meaning. However, this influence on the interpretation might have a default character. Thus, it only applies where the particular contextual conditions do not prevent

it from applying. In the context Searle supplies, the interpretation of cut as in ‘cut

the grass’ is rendered less likely as being the intended reading, than the reading as

in ‘cut the cake’. As Searle argues, this reading of cut in the given context does

not seem to be a non-literal reading of cut, since, intuitively at least, it does not

seem to be derived from some clear basic, underlying meaning. However, assuming

that the reading only comes about, or is interpretable as intended, in a particular

context of utterance, suggests once again that literal meaning should not be taken

to be a phenomenon of context-free sentence meaning. If that is the case, then the

concept of literal meaning is not applicable at Searle’s level of sentence meaning, but

18

Against the Standard Notions of Literal Meaning and Non-literal Meaning

rather at some context-dependent level of meaning. Be that as it may, Searle still

assumes that literal meaning is the basis for any non-literal meaning. It is speakers

who may use some expression or other non-literally. Thus, non-literal meanings

have to be intended and should be expected to be consciously recognisable as such.

That is, speakers should have no difficulty identifying some reading as being nonliteral, as they have to intentionally use some expression ‘deviantly’ in order for that

expression to get interpreted non-literally.

Although Searle thus argues against the view according to which literal meaning

is determined by the linguistic system alone, he does not want to deny that sentences in fact do have literal meanings. ‘Literal meaning, though relative, is still

literal meaning.’ (Searle 1978, cited from Searle 1979, p. 132). However, he applies

the concept of literal meaning to those cases in which the speaker means what she

says, contrasting them with those cases in which the speaker means more, or something different from what she said (e.g., cases of irony, conversational implicature or

indirect speech acts). Thus, although Searle identified literal meaning as belonging

to the level of sentence meaning, actually the differentiation between literal and nonliteral utterances seems to hold at the level of utterances. However, he also argues

that literal meaning is a relative notion. That is, it is rather likely that what we

take to be the literal meaning of the utterance of some sentence will depend heavily

on the specific circumstances in which the utterance of that sentence takes place.

This is in agreement with uses of the term literal meaning where it refers to an

utterance’s meaning, in contradistinction to the meaning intended by the speaker of

that utterance.

Similarly to Searle, Bierwisch (1979, 1983) assumes that what is called the literal meaning of an utterance of some (simple or complex) expression is not identical

to the linguistically determined meaning of that expression. Thus, Bierwisch also

places literal meaning at a level of meaning that is no longer independent of context, namely the level of utterance meaning. Utterance meaning is the meaning an

utterance token of an expression has when it is used in a context. The utterance

meaning can be equivalent to the utterance token’s literal meaning, but it does not

necessarily have to be. Therefore, Bierwisch differentiates the literal meaning of an

expression from its utterance meaning. Crucially, an utterance token of an expression can only have literal (or, for that matter, non-literal) meaning in a context.

With respect to this assumption, Bierwisch and Searle hold similar views. That

is, what is called the literal meaning of an expression is not determined language

internally, rather, it is dependent on certain background assumptions (Searle) or a

particular context of utterance (Bierwisch). Thus, literal meaning is a special case

of utterance meaning. A consequence of such a view is the assumption that the

lexical semantic representations of simple expressions do not encode what we take

to be their literal meaning.

What has been said sofar, corroborates a suspicion expressed at the beginning

of this section. That is, one has to ask whether the particular standard characterisation of literal meaning might not be very much influenced by our characterisation

of the field of semantics. Thus, consider again that, traditionally, semantics takes

as its starting point sentence meaning of which it assumes that it is both contextindependent as well as propositional. Because it is taken to be context-independent,

Literal Meaning and Context-Independence

19

it seems to be what the sentence literally expresses. However, we saw that, for a

large number of sentences, it cannot be said that they express propositions, unless

contextual information is first taken into account (e.g., cases of reference resolution,

fixing of indexicals and disambiguation). That is, sentence meaning and ‘propositional content of an utterance’ are not equivalent. Furthermore, as we saw from

Searle’s remarks, actually, what we take to be the literal meaning of a complex expression, is dependent on the context in which that expression is uttered. That is,

essentially, literal meaning seems to be context-dependent after all.

Thus, it seems reasonable to posit a partial new characterisation of the terms

sentence meaning and literal meaning (with respect to sentences). Whereas the former is the meaning of a certain type of complex expression and characterised by

the facts that it is compositional, context-independent and (more often than not)

sub-propositional, the latter is a certain type of meaning a sentence may have when

used in a context that allows a literal interpretation and in which that sentence

expresses a full proposition. What this characterisation of literal meaning suggests

is that whatever differentiates between literal meaning and non-literal meaning cannot be the criterion of context-(in)dependence. Moreover, this characterisation of

literal meaning (with respect to sentences) makes it equivalent to a particular type

of proposition. Thus, a new question arises, namely, how this particular type of

proposition is characterised. That is, which conditions does a proposition have to

fulfil for it to be literal in meaning? This is a question which is very close to the

core of the discussion around the semantics/pragmatics distinction and we will come

back to it in the following chapters.

meaning

context-independent

context-dependent

lexical m. sentence m.

...

underspecified

literal

...

...

non-literal

Figure 2.5: Revised differentiation of types of meaning

2.1.3

Literal Meaning as Primary to Non-literal Meaning?

The traditional view of the interpretation process assumes that an utterance’s literal meaning is always activated first. Potential non-literal meanings only get activated as a result of the literal meaning’s not fitting in the respective context. This

view, of course, is based on the traditional assumption about literal meaning being

context-independent. Since this allows an interpretation of the literal meaning of an

20

Against the Standard Notions of Literal Meaning and Non-literal Meaning

utterance without taking recourse to contextual information, it will be computed

automatically. If afterwards it becomes apparent that the literal meaning does not

fit the contextual circumstances, a reinterpretation will take place, resulting in a

non-literal interpretation of the utterance (call this the standard pragmatic view).

This is essentially how Grice must have viewed the relation of literal meaning

and non-literal meaning, since he described different kinds of non-literal meaning,

such as irony and metapor, as being conversational implicatures, that is, inferences

that require a prior recovery of what is said by an utterance. Of this latter level of

meaning, Grice said that it is very closely connected to the conventional meaning of

the words or the sentence uttered by the speaker. Specifying on this characterisation,

what is said has been taken to be the fully propositional semantic form of the

utterance resulting from the processes of disambiguation, reference resolution and

fixing of indexicals, where these processes already are of pragmatic nature since they

involve contextual information (see figure 2.6).7

Semantics

lexical meaning

semantic composition

sentence meaning

Pragmatics

does not involve any

non-literal meaning

reference resolution

fixing indexicals

disambiguation

what is said

basis for further

pragmatic inferences

conversational implicature

speech acts

...

may involve

non-literal meaning

what is meant

Figure 2.6: (Non-)Literal meaning and Grice’s levels of what is said/what is meant

Thus, what is said, being a full proposition, provides the basis for further inferences about what the speaker actually meant with his utterance. That is, conversational implicatures are derived from the fact that the speaker said what he said in

the particular way he did and with respect to a number of conversational maxims,

which are taken to underlie human communication. Since what is said includes the

conventional meanings of expressions, it is traditionally assumed to be the level at

which literal meaning is expressed. And since Grice, similarly to Searle, viewed nonliteral meaning such as irony or metapher, as an aspect of speaker meaning, what is

meant is the level of meaning at which such non-literal meaning aspects come into

play. Thus, since for the recovery of what the speaker meant we first have to know

what the speaker said, interpretation of the literal meaning of an utterance is prior

to the interpretation of a potential non-literal meaning. Moreover, since non-literal

7

Note that this fact is independent of the assumption that what is said constitutes the level of

meaning from which conversational implicatures are determined. That is, even if what is said is

not viewed as wholly semantic, the standard pragmatic view could still hold in that what is said

still forms the basis for drawing further inferences and thus has to be determined first.

Literal Meaning and Context-Independence

21

meaning aspects such as irony or metaphor rest on the violation of a conversational

maxim, they will only get derived if the literal interpretation, that is, what is said,

cannot possibly be construed as the meaning intended by the speaker.

Interestingly, although arguing against viewing literal meaning as solely linguistically determined, Searle shares the view according to which literal meaning is

prior to non-literal meaning. Thus, in his (1979) paper, Searle says of metaphorical

and ironical utterances, that their respective interpretations are arrived at by going

through the literal meaning of the sentences used to make the utterances. Thus, he

seems to assume that although a sentence’s literal meaning can only be determined

against particular background assumptions, in terms of the temporal progression of

the interpretation process, literal meaning is a necessary intermediate step in the

interpretation of non-literal meaning.

Fortunately, with the methods developed in psycholinguistics, the assumption of

the primacy of literal meaning as an assumption about the operational sequence of

the interpretation process has become empirically testable. And in fact, results of

experiments employing different methods in examining the understanding of various

types of non-literal meaning in comparison to literal meaning show that the standard

pragmatic view makes the wrong predictions. That is, in terms of cognitive effort,

the standard pragmatic view predicts that interpreting non-literal meaning should

be cognitively more exacting than the interpretation of literal meaning. Given that

reaction or reading times mirror the relative cognitive effort involved in interpreting an utterance, results such as the following suggest that the interpretation of

non-literal meaning does not necessarily differ from that of literal meaning. Thus,

Gibbs (1994) mentions an experiment (Ortony et al. 1978), where subjects were

presented with sentences in a context that was either literal or metaphoric. The

hypothesis that was tested in the experiment was that people may not have to analyse the literal interpretation of a metaphorical utterance before actually deriving

the intended metaphorical reading. The hypothesis was confirmed. Thus, although

subjects took longer to read metaphorical targets than literal ones in short contexts,

in long contexts, there was no difference in reading times for the metaphorical and

the literal target sentences. These results suggest that the richness of contextual

information available during the interpretation of an utterance has an effect on how

difficult it will be to give that utterance a non-literal interpretation. Another experiment showed that utterances may be interpreted non-literally although there

are no conditions that trigger the failure of a literal interpretation, suggesting that

people automatically apprehend the metaphorical meaning of an utterance (Glucksberg et al. 1982). The task was to judge sentences such as Some jobs are jails as to

their literal truth. Thus, it was not necessary to seek a non-literal interpretation for

the sentences, subjects only were asked for the literal truth of each sentence. Now,

if for a non-literal interpretation of a sentence a pragmatic triggering condition is

required, sentences such as Some jobs are jails should simply be considered as false.

If, however, people automatically interpret the metaphorical meaning of such sentences, then the ‘false’ judgement for the literal reading of the sentence should be in

conflict with the ‘true’ judgement for the non-literal reading of the sentence. And

in fact, although subjects correctly judged sentences such as Some jobs are jails

as literally false, if a metaphorical interpretation for the sentence in question was

22

Against the Standard Notions of Literal Meaning and Non-literal Meaning

available, subjects took much longer to make that judgement. Thus, apparently, the

metaphorical meanings were automatically interpreted, without the need for some

pragmatic triggering condition (i.e. maxim violation). This suggests that the interpretation of non-literal meaning does not rely on the violation of some conversational

maxims or principles. Moreover, it shows that, although context may facilitate the

interpretation of an utterance as non-literal, it is not absolutely necessary.

Note, however, that more can be said with respect to such examples as Some

jobs are jails. Thus, although it is true that there does not seem to be a pragmatic triggering condition such as maxim-violation for a metaphoric interpretation,

nevertheless, it can be argued that in cases such as this, there is some triggering

condition, either semantically or pragmatically induced. To repeat, the standard

pragmatic view assumes the literal meaning of an utterance is interpreted first and

only if this does not fit the contextual circumstances a non-literal interpretation is

determined. The problem with sentences such as Some jobs are jails or, for that

matter, The ham sandwich is sitting at table 7 is that it is not clear what their literal

meaning should be (cp. Stern 2006). Thus, the longer reaction times measured in

the experiment mentioned above might be due to the fact that whatever component

is responsible for this stage in the interpretation process is having problems determining a literal interpretation for the sentences in question. This, in turn may be

sufficient to trigger an alternative, non-literal interpretation (cp. Dascal 1987).

Keysar (1989) takes up this criticism and shows that even in contexts were a

particular sentence is understood as literally true, that sentence’s potential but false

metaphorical meaning interfers nevertheless. Thus, subjects were asked to judge test

sentences as true or strongly implied to be true after having read small texts. The

texts consisted of two parts, were one part related to the literal interpretation (L) of

the target sentence, rendering it either true (L+) or false (L-), and one part related

to the metaphorical interpretation (M), again rendering this either true (M+) or

false (M-). Thus, texts were (L+M+), (L-M+), (L+M-) or (L-M-). For example,

one of the test sentences was Bob Jones is a magician. An example text for which

that sentence is interpreted as literally true but metaphorically false (L+M-) is given

below.

Bob Jones is an expert at such stunts as sawing a woman in half and

pulling rabbits out of hats. He earns his living travelling around the

world with an expensive entourage of equipment and assistants. Although Bob tries to budget carefully, it seems to him that money just

disappears into thin air. With such huge audiences, why doesn’t he ever

break even? (Keysar 1989, p. 378)

The results show that subjects are quickest in responding after texts that rendered

the target sentence both literally and metaphorically true (L+M+). Generally, they

are quicker in responding in congruent contexts (i.e. L+M+ and L-M-) than in

incongruent ones. Thus, as in (Glucksberg et al. 1982)’s experiment, subjects take

longer judging literally false but metaphorically true sentences. Crucially, however,

they also take longer judging literally true but metaphorically false sentences, indicating that even in such a situation the potential metaphorical interpretation of the

sentence is computed. This result shows that the longer reaction time measured by

Non-literal Meaning and Conventionality

23

(Glucksberg et al. 1982) for literally false but metaphorically true sentences is not

due to the difficulty of determining a literal interpretation for those sentences in the

first place, as similar results are achieved in situations in which the target sentence

actually is literally true but metaphorically false.

Summing this section up, the conclusion one can draw from examining different

empirical studies is that it is not generally necessary to compute the complete literal meaning of an utterance before deriving that utterance’s intended non-literal