Laura Penttinen A RESEARCH UPON SCHOOL UNIFORMS AND

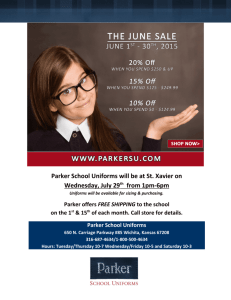

advertisement