Healthy Aging in Canada: A New Vision, A Vital Investment From

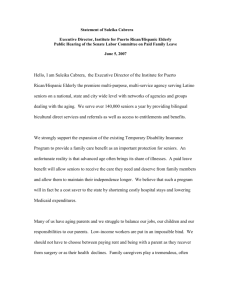

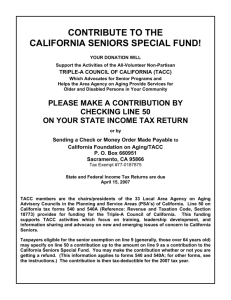

advertisement