WRITING IN ARTS AND SCIENCE Report of the Ad

advertisement

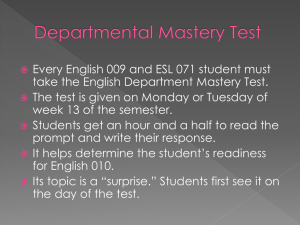

WRITING IN ARTS AND SCIENCE Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Writing, March 2004 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Ad Hoc Committee on Writing reaffirms the commitment of the Faculty of Arts and Science to the integration of writing into our undergraduate curriculum. Although the 1999 Resolution calling for a writing component in every program has been only partially fulfilled, courses across the disciplines continue to use written assignments, often in innovative and cost-effective ways, and students recognize the importance of writing by seeking instruction at writing centres and in writing courses. Through experimental initiatives and analysis of ongoing work, the FAS has identified best practices and begun to define measures for success. We have developed a stock of relevant instructional resources and have established a cadre of expert writing instructors. This report identifies several challenges in continuing to implement this commitment in a time of budget constraints. The wide variation in the proficiency levels of our incoming students requires flexible and innovative teaching, including the design of assignments so as to deter plagiarism. With increasingly large classes, we must rely on Teaching Assistants who are not always prepared to recognize the variety of student needs, coach students effectively, or grade written work helpfully. The positioning of writing centres at the colleges, though effective at delivering tailored instruction to individual students, discourages the development of instruction linked to specific courses or disciplines. We have nevertheless identified ways to build on our achievements so far and continue developing our resources and teaching strategies. The following options for action could be implemented separately, but would work best together. If resources permit, we recommend that all be chosen and funded for the next five-year period, then reviewed at the end of that period. An early task of the proposed committee would be to establish appropriate measures for evaluating achievement over the planning period. Our report also offers a list of more farreaching ideas for consideration. 2 OPTION A: Establish a committee to coordinate writing instruction across the Faculty of Arts and Science. Reporting to the Dean and representing chairs, principals and writing instructors, this body would help set directions for the Faculty and would enhance the equitable and efficient use of current resources, including those now flowing to writing centres. It would also be in a position to coordinate new initiatives or activities. COST: minimal or none. OPTION B: Reinstate the transcriptable non-credit writing courses supported by Quality Enhancement funding and mounted at the colleges. These courses addressed identified gaps in current instruction (science writing, ESL writing, and critical reading) and responded to high student demand, giving nearly 200 students an intensive learning experience. They would be particularly suitable for intersession and summer offerings. COST: about $50,000 yearly. OPTION C: Create a centralized pool of writing instructors to work with departments and courses. The establishment of a pool of working instructors to work with departments and courses, perhaps by seconding some of the time of experienced instructors in college writing centres, plus the provision of seed money for transformational projects within courses, would connect writing instructors with TAs and course instructors to establish viable methods of writing instruction in specific courses. It would provide a flow of ideas between the disciplines and the writing centres, and would allow the Coordinator of Writing Support to plan more comprehensive types of group instruction. It would also provide data for further study and for measurement of outcomes. COST: about $100,000 yearly. 3 WRITING IN ARTS AND SCIENCES Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Writing March 2004 Advisory to Dean Pekka Sinervo Membership: David Cameron (Chair), Brian Corman, Corey Goldman, Mariel O'Neill-Karch, Margaret Procter The Faculty of Arts and Science recognizes the value of writing as part of students’ empowerment as learners and future professionals, and remains committed to integrating opportunities and instruction in writing within students' programs. This committee was struck to review progress during the last planning cycle and to define the specific challenges concerning this integration of writing into the curriculum. The following Resolution on Writing was passed by the General Committee in 1999: a) b) c) d) That every major and specialist program in the Faculty of Arts and Science integrate writing components into its program requirements. That the FAS assist in the re-design of key First Year courses so that they incorporate writing components. That the FAS develop criteria by which to approve and evaluate existing / proposed writing components in programs. That the above be implemented incrementally during the period 1999-2004. It is obvious that not all these goals have been achieved. However, some modest progress has been made. We can identify several distinct successes in programming and resource development along the lines of this Resolution, and can see opportunities for building on past initiatives. This report outlines the direction of recent efforts, assesses the main remaining problems, and suggests a menu of adjustments that could make efficient use of limited resources. We focus on structural changes that could be made at different levels of modest cost. ASSESSMENT OF PROGRESS The Arts and Science response to the Green Papers in February 2003 cited the 1999 Resolution and reaffirmed the importance of teaching writing as part of student programs, stressing the 4 commitment of departments to this enterprise.1 In spite of inherent difficulties, programs and courses continue to build writing into their expectations. In a 2002 survey for the Educational Advisory Committee, 19 of 38 departments and programs claimed that the use of writing was increasing in their courses.2 Though this self-reporting cannot be taken as proof in itself, the heavy and growing use of writing centres by students from all years and programs3, along with the strong demand for writing courses4 and online resources5, provides one type of evidence that students have to write within many courses and that they have been led to recognize writing as an important part of their learning. Faculty members and Teaching Assistants are also interested in methods of incorporating writing into their courses, as demonstrated by their increasing attendance at workshops and their use of print and online advice on such matters as deterring plagiarism, designing assignments, and assessing written work.6 Their commitment to the use of writing to learn is also evident in the prevalence of inventive assignment design in current courses (for instance, the use of an international survey questionnaire for constructing a sequence of analyses in POL103Y) and the innovative use of such alternative forms of writing as online conferencing to extend class discussion (the most famous of which is the BIOME website for cohorts of science students). It is now standard for courses to include a reference to the importance of writing as part of their syllabi. The First-Year Seminar program continues to define itself in part by its attention to oral and written communication. The recent EAC study of 199Y courses7 confirmed that in most of them, students write multiple and varied assignments and receive extensive feedback. In response to student requests, 100-level English literature courses were revised several years ago to include more instruction on writing. In many programs, the second-year courses required as part of major and specialist programs make instruction in discipline-specific literacy skills an explicit focus (for instance, BIO250Y and SOC203Y). As well as retaining senior theses and seminar classes, a few science programs have developed upper-year specialist courses on disciplinary writing and communication (for instance, PSL497H). Innis College has recently developed new courses with an interdisciplinary focus on 1 See www.artsandscience.utoronto.ca/green/response.html#(c)%20Student%20Writing. Two of the three departmental responses quoted focus on the use of 199 courses for this purpose. 2 Mariel O'Neill-Karch, table summarizing results, presented September 2002 to the Educational Advisory Committee, included in Appendix A. 3 David Clandfield, Report on Writing Programs in the St. George Colleges (Fall 2002) and its followup analysis of budget structures and proposal for OTO funding (Spring 2003), included in Appendix A. These documents detail the heavy demand and long waiting lists for individual appointments; all writing centres are fully booked nearly all year long. 4 More than 20 sections of ENG100 are offered each year, as are up to 7 sections of courses in the Innis College minor program in Writing, Rhetoric, and Critical Analysis and several courses offered at other colleges. For a list of courses currently available, see the leaflet Writing at the University of Toronto (attached in Appendix C) and the webpage www.utoronto.ca/writing/courses.html. 5 Usage of the online advice files in the website Writing at the University of Toronto (aimed mainly at the types of writing done in Arts and Science) at www.utoronto.ca/writing/advise.html has grown incrementally to about 50,000 hits a week. Over 4000 students in Arts and Science have used iWRITE as part of their courses since its creation in summer 2001. See www.utoronto.ca/writing/iwrite/demo.html for a description of this software program, developed at the request of the Arts and Science Committee on Writing. 6 Over 70 faculty members attended an Arts and Science workshop called "Facing Up To Writing" offered in May of 2002. OTA sessions on deterring plagiarism, designing assignments, and handling intercultural communication have attracted several hundred more faculty members. The Teaching Assistants' Training Program offers at least three sessions yearly on grading and giving feedback, attended by nearly 200 TAs. The non-credit course Teaching in Higher Education (THE500H) includes a class on Faculty and Student Writing in each session, serving about 125 students yearly. The "Faculty and TA Resources" section of the Writing at U of T website (www.utoronto.ca/writing/ faculty.html) typically receives over 600 hits a week during term. 7 Margaret Procter, Report of EAC Subcommittee on 199Y Seminars, March 2004. 5 writing as part of its Writing, Rhetoric and Critical Analysis minor program.8 These developments confirm that the Faculty of Arts and Science recognizes writing as part of its core activities, and that it can generate appropriate models for teaching it. The writing initiatives sponsored by the Committee on Writing during 1999-2001 encouraged innovative uses of writing for learning in specific courses and provided testing grounds for new teaching methods. The experiments were thoroughly studied and evaluated.9 Though empirical evidence is hard to obtain for such small interventions, and some projects met resistance from students surprised at finding that writing was part of their disciplinary courses, the studies found consistent agreement among students and faculty that course material was learned in more depth when writing was used to explore it.10 Gains in clarity and organisation of written work were also identified both by TA accounts of differences from past years and by analysis of student samples collected throughout the courses. Another testimonial to the value of these teaching methods is that five of the eight main course projects have continued to operate using departmental funds. A summation of best practices -- including some warnings about inappropriate or unsuccessful efforts -- is in print and online circulation as a faculty handout.11 Among other outcomes, these initiatives helped define the ways that Teaching Assistants can serve as writing instructors, and they resulted in the collaborative development of several types of instructional material. The method of online group feedback in ENV200Y, for instance, has been adopted for other courses, as have tutorial exercises developed for HUM101Y and a criteria sheet developed for SOC203Y. The web-enabled software iWRITE12 was created as a followup to these initiatives, supported by two provostial ITCDF grants matching seed funding from Arts and Science and RCAT, and by a further small grant from McGraw-Hill-Ryerson. Coursespecific versions of iWRITE have now been developed for eight courses in Arts and Science (as well as six courses elsewhere at U of T and at York and McGill), including most recently ENG185Y in the Woodsworth College Academic Bridging program and BIO349S, a key course in Life Science programs. The seven college writing centres have also consolidated their teaching function within Arts and Science. Their trademark method of offering individual instruction on work in progress across the curriculum has been validated by several internal studies and the testimony of strong student 8 The program has built on writing courses taught at Innis College since the 1970s and has consulted widely with faculty in other disciplines in designing its minor. See the website at www.utoronto.ca/innis/writingprogram.htm. 9 See Appendix A for summary reports from these initiatives. More detailed accounts of student focus groups and course assessments are available in the files of the Committee on Writing. See also Appendix B for a series of background papers done for this project and others within Arts and Science: they deal with such topics as different designs in ESL programming, empirical research on instructional methods, and best practices in the design and positioning of writing centres at our US comparators. The total budget for the pilot projects during 1999-2001 was in the order of $160,000 to fund additional TA time within courses, with an additional $32,000 allocated to development of iWRITE (much of which also paid course TAs to develop material for the course sites) and further small amounts to a literature-search project and the faculty workshop of May 2002. 10 See for instance, the chart summarizing course projects and evaluations, and multiple student and faculty comments throughout other reports on the writing initiatives, all included in Appendix A. This finding is entirely consistent with the literature on empirical evaluation of Writing in the Curriculum projects, as summarized in the inventory prepared by Dana Mushkat of Sociology in September 2002 (also included in Appendix B). 11 The handout version is included here as part of Appendix A. The online version at www.utoronto.ca/writing/artscilessons.html also includes live links to some of the instructional material developed initially for these course initiatives. 12 See the description at www.utoronto.ca/writing/iwrite/demo.html. Most of the currently active sites may be visited by visiting the gateway site www.iwriteweb.net and using the login guest1 and the password demo1. 6 demand. 13 The flexibility of this method is particularly suited to the wide range of student needs (including those of students learning English as a second language) and the diversity of courses within Arts and Science programs. College writing centres have also developed several series of non-credit courses and group workshops on academic skills, offered at their colleges but usually open to all undergraduates.14 These are key components of the summer intake and orientation programs organized by college registrars. Some of the college writing-centre directors (like those at the suburban campuses) now consult informally with faculty members and TAs in their college programs, and at New College two programs incorporate some co-instruction by a writing instructor within their courses. Deborah Knott and Jerry Plotnick of New and UC respectively have produced instructional handouts that are in general use across the faculty and beyond,15 and Patricia Golubev of Trinity and SMC has published a textbook on science writing with University of Toronto Press.16 Though each of the college writing centres operates independently, and each reports separately to a college principal, regular professionaldevelopment sessions and meetings have led to widening of expertise in ESL instruction and specific types of writing in the disciplines (especially science writing). They have also brought much greater consistency of operation and some useful practical collaborations (e.g., online booking systems, a common feedback form, and interchanges of student workshop sessions). The colleges also allocated more than half of their Quality Enhancement funds to develop three non-credit but transcriptable WRT courses in areas identified as needing specialized instruction: scientific writing, critical reading and writing, and ESL writing. College writing instructors now include 15 people with full- or part-time appointments as Lecturers or Senior Lecturers, many of whom also teach in departmental or college programs. Their work in the college writing centres now constitutes about 7 FTEs in total. They form a considerable reservoir of writing expertise. SITUATION: PROBLEMS, THREATS, AND OPPORTUNITIES Even with these achievements, it is clear that Arts and Science still cannot claim that all its graduates have been given experience and instruction in writing, much less that they can all write competently. Lack of language proficiency remains a concern. About two thirds of our students learned English as a second language, and about half always speak a language other than English at home.17 Although only about 5% of our entering students have to present a score from TOEFL or another standardized proficiency test,18 many others are still learning English and lack confidence in their English skills. A great many of our students lack familiarity with the language of academic discourse, and even with the habit of reading. The new secondary curriculum may eventually bring about more consistent preparation in academic writing, but at present the levels of experience and confidence remain very uneven. It is not surprising that 13 The Clandfield reports of 2002-3 (excerpts included in Appendix A) provide detailed figures on usage and types of instruction, along with summaries of measures of success. See also the 1999 review of the Innis College Writing Centre and other assessments within college reports. Recent formal external reviews of the SGS Office of English Language and Writing Support and the UTM Academic Skills Centre have been highly positive about similar mixes of instructional methods. 14 See Appendix C for sample flyers from University College, Victoria College and Woodsworth College. 15 See the handouts by Deborah Knott and Jerry Plotnick attached in Appendix C. 16 Andrea Gilpin and Patricia Golubev, A Guide to Writing in the Sciences (University of Toronto Press, 2000). 17 Figures from John Kirkness’ survey of entering undergraduates in first-entry programs, 1997. The University of Toronto National Report, 2002, states that 36% of students currently enrolled in first-entry undergraduate programs were born outside Canada. 18 Doug McBean, office of the University Registrar, personal communication. 7 some students continue to avoid courses where their problems with English would be exposed,19 and that many faculty and TAs express concern about the challenge of using written assignments for assessment when a high proportion of their students cannot meet basic standards of English competency. Arts and Science has chosen not to offer credit courses in ESL or basic writing, much less require them, but there is a clear need to make other types of ESL and writing instruction widely available and relevant to students' programs. Other factors have become even more acute recently, and in combination constitute immediate threats to our commitment to writing in the disciplines. The sudden rise of Internet plagiarism (or the sudden recognition that it was happening), recent surges in class size, and continuing pressures on TA budgets have started to discourage many course instructors from giving essay assignments and research papers. In-class tests now constitute a surprising 25% of assessment across the Faculty, the same as the weight given to essays. In classes with more than 200 students, essays form only about 10% of the work.20 This trend towards relying on in-class writing deprives students of chances to work intensively on drafts and diminishes attention to the quality of writing in itself. It also means that writing is being used more to display given knowledge than to explore new ideas. The implementation of turnitin.com software is generally felt to have helped deter flagrant Internet copying, but if we are to retain the commitment to research-based writing, more attention needs to be paid to helping faculty design plagiarismresistant assignments and instruct students on the critical evaluation of print and Internet sources. Pressure on TA resources is a key factor in this erosion of written assignments. Directly counter to the 1999 Resolution, several first-year courses are currently facing the need to cut back or eliminate written work because of concerns over TA costs: among them, for instance, is PSY100Y, in which 20% of first-year students are enrolled. Other key courses such as SOC101Y and SOC203Y have responded to changes of instructor by reverting at least temporarily to multiple-choice tests, and even some History and English courses have begun using similar easyto-grade questions that reduce opportunities to write reflective or analytic answers. William Michelson's recent study on the effects of growing class size shows a clear negative relationship between student satisfaction with the learning experience and the use of "impersonal" types of assessment rather than essays.21 We will diminish the value of all our students' learning experience if large class size is not counterbalanced by more sophisticated instructional methods. The reliance on TAs as coaches and graders for written work also builds in other dangers as well as opportunities. TAs are in an ideal position to offer timely and focussed instruction on literacy skills in their disciplines, but not all TAs are confident or competent in filling this role. Nor are they always given the opportunity to work from their strengths. In studies of the 1999-2001 initiatives, students told us strongly and clearly that they resented being asked to do written assignments when they did not receive adequate or consistent instruction and when they felt graded unfairly, especially when grading seemed to focus heavily on stylistic elements on which they had received no instruction.22 Even in the supported course initiatives, they felt that they 19 For instance, in a survey undertaken in February 2004 for the EAC report on 199Y courses, 31% of the 1808 respondents who did not take a 199 course said they made that choice because they did not want to write essays (10%, n=185) or make oral presentations (20%, n=367). 20 William Michelson, Enrolment Matters: Instructors’ Assessments of Students - Course Characteristics and Impacts, 2003 (report for the Educational Advisory Committee), www.artsandscience.utoronto.ca/ teaching/enrolment_matters.pdf, page 6. 21 Michelson, Enrolment Matters, page 13. 22 See especially the reports from the student focus group for PHY256Y and the online surveys for Helen Rodd’s BIO courses. 8 were sometimes still being assessed on their writing without being shown what to aim at. (The creation of iWRITE was a direct response to this complaint.) TAs also expressed frustration at being expected to fulfil so many functions in their limited time allocations, especially where they had no or little chance to confer with the course instructor or each other on assignment design or grading expectations. These issues remain concerns for TAs across Arts and Science. The workshops on grading offered by the TA Training Program attract hundreds of participants each year, but this program cannot monitor actual work or offer continuing support within courses. The best models of TA contributions to the writing initiatives came from courses where TAs were expected to confer and work together, where they had a chance to shape the assignments and grading criteria, and where they had some opportunity (and sometimes assistance from writing specialists) to give instruction or formative feedback as well as to grade. The faculty members who worked with their experienced TAs in formulating their assignment instructions expressed satisfaction at the improvements they gained. Another effective and inexpensive strategy was to bring TAs together for an hour at the start of a grading project so they could discuss a "benchmark" paper. These conditions required some initial time allocation, but they also created efficiencies by formulating clearer expectations and improving the consistency of feedback and grading.23 Another underused resource for course instructors in the Faculty is the pool of expertise available in college writing centres. At present there is no structural link between the writing activities in departmental courses and the teaching capacities of college writing instructors. Students may (and do) seek out the individual and group instruction offered by these college-based operations, but course instructors and TAs have virtually no opportunity to call on them to provide or enhance the writing instruction needed within their courses. Although college writing instructors are often frustrated by seeing students struggle with unclear or flawed assignments, they lack opportunities to ask course instructors for clarification or to offer suggestions. Nor can they offer to perform duties outside the scope of their college mandates or reporting structures. They give generic group workshops at the colleges, but except for college programs, they cannot set up course-specific sessions. Lacking control of their own budgets (or even clear information in some cases), they cannot even plan for future initiatives. Funding increases usually come during term as OTO grants, so that they can be applied to increasing individual instruction but not to initiatives requiring coordination and planning. These limitations make Arts and Science the exception within the University. In the professional faculties, the suburban campuses, and the School of Graduate Studies, the newer writing centres are able to initiate instructional initiatives as the need arises and to work with course instructors on request.24 The integration of writing within programs is more visible and probably more efficient in these divisions as a result of their writing centres' more flexible positioning. The University Writing Coordinator, as a one-person unit, does try to implement some crossFaculty initiatives. She gives general and course-specific faculty and TA workshops, responds to calls from faculty and TAs about designing assignments and providing instructional material, 23 In the 1200-student course BIO250Y, the need to re-mark assignments dropped from 15% to under 5% with TA training, clearer assignment design and the use of iWRITE. In HUM101Y, TA training sessions on grading specific papers and teaching methods diminished plagiarism from a plague to a nuisance. Collaborative work among TAs in SOC203Y also reduced rampant plagiarism from 30 cases in 2001-2 to 3 cases in 2002-3. 24 Links to websites describing the activities of these writing centres are available at www.utoronto.ca/writing/centres.html 9 and gives at least ten class presentations yearly at the request of course instructors. Some of these opportunities derive from her work in implementing iWRITE for specific courses. For the last two years, along with instructional librarians and a learning counsellor from CALSS, she has helped put on a week-long set of student workshops on library research papers for Arts and Science students.25 Though well regarded and efficient, this type of work is limited by her individual availability. Because of the college-based reporting structure of the relevant writing centres, she cannot call on colleagues in college writing centres even to help with these limited initiatives, much less to develop further programming. This structural barrier to instructional activities that are clearly needed is an unfortunate inefficiency within Arts and Science. OPTIONS FOR ACTION Given the centrality of high-level literacy to its teaching activities, and its record of attention and achievement so far, the Faculty should renew its commitment to the model of integrating writing instruction within the disciplines. This commitment is consistent with directions in other areas of the University and in other public research universities.26 Even with limited resources, Arts and Science should build on the interest and concern about writing expressed by its faculty and students, and should plan to maximize the effectiveness of the instructional resources already in place. We recommend the following changes as ways of addressing the problems and threats outlined above. They all aim at making better use of the resources and opportunities available. These options are presented in order of additional cost. They could be adopted independently, but are intended to work together cumulatively. A. MINIMAL COST: Continue with the current level of commitment and resources, and create a committee to coordinate writing instruction as an enterprise across the Faculty of Arts and Science. We recommend the creation of a coordinating committee reporting to the Dean and consisting of a Vice-Dean, two college principals (one of them from a federated college), two college writingcentre directors (representing different colleges than the principals), at least two department chairs or program coordinators, and the University Coordinator of Writing Support. This committee would work to clarify the aims of the various types of writing instruction currently offered within Arts and Science and help create and solidify connections among them. Liaison with the Educational Advisory Committee would provide for sharing of information and collaboration with other cross-Faculty initiatives. The committee should undertake studies and assessments as needed and continue to measure progress towards the stated goals of the Faculty. Without impinging on colleges' control of their own programs and budgets, and keeping in mind particularly the 1998 Memorandum of Agreement with the colleges,27 the committee should 25 See the flyer included in Appendix C. The five sessions each year were each attended by about 50 students, and they received very high ratings for their relevance of focus and appropriateness of instruction. 26 See the report on US comparator universities prepared as a background paper for David Clandfield, included in Appendix B. 27 The Memorandum of Agreement between the University of Toronto and the Federated Universities (July 1998) notes that colleges have "special responsibilities" for the development of their students' academic skills, and affirms 10 review the use of resources flowing from Arts and Science to the college writing centres, especially the equalization funding instituted in 2003-4.28 It should also monitor any Facultysponsored course initiatives in writing in order to measure and disseminate their results. This committee would encourage cooperation among writing centres and among writing centres and departments, and would enhance the equitable and efficient use of current resources The responsibilities of this committee would be adjusted as more funding flows from Arts and Science for the additional recommendations below. B. SMALL COST: Reinstate the transcriptable non-credit writing courses supported by Quality Enhancement funding. All nine sections of the three WRT non-credit courses were suspended last year for the period of the double cohort so that their QE funding could be used to mount more sections of the 199 courses. These specialized courses addressed specific areas of need identified by discussions within the Writing Committee and the EAC and by the findings of the 1999-2001 course initiatives. Their topics were, respectively, scientific writing for upper-year science students, ESL writing for self-identified non-native speakers, and critical reading and writing for students needing to develop this academic skill and outlook. They were in high demand by students and were very highly rated in course evaluations and by student reports of consequent success.29 Some of these courses would be ideal for intersession offerings, and some could be given in the summer. We recommend that the WRT courses should be reinstated as soon as possible, using OTO funding for 2004-5 if necessary. The total cost in 2002-3 for all nine sections was just over $50,000, half of the colleges' allocation of QE funding.30 We recommend re-establishing this QE money as soon as possible and instituting an additional $20,000 as a yearly transfer to allow for increased salary costs and some expansion in the future. Since this portion of the QE funding flows through colleges, the colleges should continue to administer practicalities such as room bookings and contracts, and the course instructors and TAs should continue reporting to the relevant college principals (or to one principal if delegated by the others). The coordinating committee as in Option A above would, however, take responsibility for monitoring the courses' focus and impact as part of the overall aims for writing instruction in Arts and Science. that "In co-ordination with services offered by other units in the University, Colleges shall offer programs, workshops, labs or tutoring in such areas as: a. proficiency in language, reasoning, and writing, b. mathematical sciences and analytical proficiency, c. computer and computing skills." The coordination we envisage falls well within this arrangement. 28 In 2003-4, responding to David Clandfield's study of the college writing centres, the Faculty allocated $30,000 to Trinity and University College to equalize access across the seven colleges. An additional $50,000 was allotted for the enrolment period of the double cohort, making the grant $80,000 in total for 2003-4. (See the document "College Writing Centres: A Formula for Increased Funding." This grant should be continued for the period of this planning cycle to allow writing centres to meet student demand for individual appointments. 29 Several reports on WRT courses are included in Appendix A. 30 Derek Allen reports this breakdown for instructor salaries (email, 18 Feb. 2004): five 6-week sections of WRT300 (Writing for Scientists), $36,827 (including 85 hours each for science TAs); two 4-week sections of WRT301 (Critical Writing and Reading), $3,705; two 13-week sections of WRT305 (ESL Writing), $9,703. Total $50,235, including all benefits. A small budget for supplies was also made available. These courses enrolled about 200 students a year. 11 C. MODEST COST In addition to Options A and B, creation of a centralized pool of writing instructors to work with departments and courses. In order to overcome the structural barriers between college writing centres and departmentallybased courses, we recommend the creation of a centralized pool of writing instructors, perhaps cross-appointed or seconded on a part-time basis from writing centres, possibly on a rotating yearly cycle. These would supplement the current resources of writing centres within the colleges, not subtract from their budgets or from their mandate to teach students individually at their home colleges. Working with the University Coordinator of Writing Support and benefitting from the public sponsorship of the Dean, they would respond to requests from course instructors and TAs for consultation on assignment design and effective methods of feedback and grading. They would also advise on the choice of appropriate instructional resources and develop new ones if necessary, including course-specific iWRITE sites. These instructors would monitor student need and offer targeted group instruction as opportunities arose, either as part of courses or as standalone workshops, including sessions with a focus on oral communication and reading skills if warranted. (It should be made clear from the start that the writing instructors would not serve as graders or correctors of student work.) Writing instructors might specialize in specific subject areas or courses. With an accompanying program of funded grants for transformational projects within courses, along the same lines as the Instructional Initiatives Grants, the effects of this new resource would be magnified. Grants for additional TA time would allow writing instructors, course instructors and TAs to work together before and during term to plan, implement, and evaluate writing instruction tailored for course needs and intended for continuing use. Projects could include development of innovative written assignments closely related to disciplinary goals, effective methods for formative and summative feedback to students, and creation of instructional resources such as websites and iWRITE sites. The practical advantages of this initiative would be far-reaching. It would signal to both faculty and students the commitment of Arts and Science to integrating writing instruction within courses. It would provide substantial enough interventions to allow for the collection of reliable information and the valid measurement of effects. It would also support the work of college writing centres, in part by enhancing the visibility of their instructors as part of course teams. The designated writing instructors would develop more expertise in the types of writing done in various disciplines and carry their knowledge back to the writing centres. Their specialized handouts and websites would be available for general use. College writing instructors confirm that the positions would be attractive for them. Much of the work would take place in the summer or the early weeks of term, thus helping even out workload and providing variety of activity to balance the intensive individual instruction concentrated in the later weeks of term. As a member of this pool, the Coordinator could also work more efficiently by being able to delegate some tasks (such as the development of course-specific material for iWRITE sites and the offering of student workshops and TA training sessions at the start of term) and by gaining the capacity to plan initiatives requiring more than one person. This operation would need several years to mature and grow, but a five-year commitment of funding, with a program review in 2009, would allow for a reasonable test of viability and effectiveness. The funding would be directed in two ways: 12 1. For salary costs of the central writing instructors, we recommend funding of $50,000 a year for the first two years, starting in 2004-5, with additional funds set aside for increases to a total of $100,000 for the next three years if recommended by the coordinating committee. This funding would provide for .25 FTE in each of two Lecturer appointments in the first two years, rising to four such increases by 2009-2010 if needed.31 Administrative costs would be minimal, especially if the writing instructors worked out of their college offices. The University Coordinator of Writing Support would provide most of the day-to-day mentoring and supervision. The instructors would continue to report to their college principals overall, and the coordinating committee as in Option A would provide the principals with a yearly assessment of this component of the instructors' work. The coordinating committee would report to the Dean on the state of this operation and would recommend increases or changes as needed. 2. To make the best use of this new resource, some of the funding from the former Committee on Writing should be made available for special projects so that courses (or departments) could make the best use of opportunities to work with writing instructors. Funding granted for specific proposals would provide TA time for working with the writing instructors on creating new instructional methods and materials, including a focus on feedback and grading. Some of this would be for additional training during the implementation period, but it should be seen as transformational short-term funding rather than as continuing additions to course funding. Proposals should be invited for the use of this funding in the same way as for Instructional Initiatives grants. The coordinating committee from Option A would evaluate the proposals and monitor progress through a system of periodic reporting, and would also help to disseminate the results. We suggest a minimum budget of $50,000 a year for project funding, with a five-year allocation until program review in 2009, as for the pool of writing instructors. Guidelines for accountability would be developed by the coordinating committee. This funding could be increased in future years if justified. LARGER VISION AND LARGER COST Though larger ideas may not be feasible in the immediate budget situation, they are appropriate to the size and status of Arts and Science as a key teaching unit in a top-rank research institution. The following concepts also relate to the special opportunities created by our population and our history. They envisage real possibilities given the needs and capacities of our students and faculty members, and could be developed further if internal resources or opportunities for outside funding were to arise. • 31 Increased funding for the college writing centres to allow them to meet current student demand, which has increased exponentially as students recognize that they are expected to write well within their courses and need communication skills for success after graduation. The equalization and OTO funding of 2003 granted in response to David Clandfield’s study This costing is based on the average salary of early-career Lecturers of about $70,000 plus benefits. It also includes some administrative costs for such things as copying and equipment. The plan to cross-appoint or second these faculty members would necessitate some new hiring at writing centres, probably at a lower salary rate. 13 has barely kept pace with demand in 2003-4, and will need to be reviewed and renewed regularly. • Increased funding for TA training and grading time. At present, TAs are often given only the two mandated hours for initial training, and are also limited to only a few minutes for each paper. Even with efficiencies of grading methods, this is not adequate to give students a sense that their writing is being read with care or interest. If applied to all courses, the costs of this type of increase would be considerable. The benefits would also be enormous. • A system of course-specific peer mentoring, as at several US and Canadian universities32 where selected and well-trained students give formative feedback and counselling about course expectations. The system gives students easily accessible informal support; the benefits to the student fellows are also considerable, often including course credit in a concurrent course. UTM has some components of this system in the form of peer mentoring, where upper-year students offer group workshops on such topics as preparing for a specific term test. The system gives the fullest results when the peer fellows have themselves received intensive instruction on writing, or when they can specialize in writing as their program of study. It requires close supervision and provision of initial training by specialized writing instructors, along with collaboration and trust from the course instructors and TAs in the target disciplines. • A system designating certain courses as writing-intensive, as approved by an official body according to stated criteria. Each department would be required to offer a certain number of such courses. Students could then be required to take them, either within their own programs or from those of related departments. As with the system for staffing 199Y courses, this would take considerable will on the part of the administration and would require some subsidies. It would be particularly challenging (but not impossible) for departments in the physical sciences. UTSC has made considerable progress in following through a 1998 Task Force recommendation along these lines. MEASURES OF SUCCESS The proposed committee should be mandated to establish appropriate measures to evaluate progress over the course of the planning cycle, calibrated to whatever course of action has been agreed upon. NEXT STEPS These steps focus particularly on the implementation of the low-cost but essential coordinating committee of Option A and the additional planning functions it would make possible. They also outline the steps necessary for timely use of Options B and C and provide for studying the 32 For instance, Harvard (where undergraduates work as paid peer tutors in one of the writing centres), McMaster (where undergraduates volunteer as peer tutors in first-year Inquiry courses and receive course credit), and Wisconsin (where undergraduates are attached as writing fellows to writing-intensive courses and give preliminary feedback on papers; they are enrolled in a concurrent credit course on teaching writing). 14 "Larger Vision" ideas if desired. The timetable indicated below is aggressive, and could be adjusted according to the pace at which it is possible to make key decisions. Spring 2004: We recommend that the coordinating committee (Option A) be set up as soon as possible. Its first priority should be to formulate its collective mandate and define its immediate goals. It would need to start by reviewing information about current resources and needs, drawing on this report and its Appendices. It could then advise the Dean on funding allocations for writing centres next year (including equalization payments and continuation of the doublecohort allowance), and could plan for efficient collaborations in summer and orientation programming. Early Summer 2004: Implementation of the centralized pool of writing instructors (Option C) would require allocation of funding in time to allow for staffing arrangements and the start of this work well before the beginning of the next academic year. The coordination committee would draw up job descriptions. If a decision were made to proceed via secondments from the writing centres, arrangements would need to be made for secondment of the two assigned writing instructors, adapting appointments as needed and allowing for any replacement hiring at the college writing centres. The committee could also advise on adjustment of the job description for the U of T Coordinator of Writing Support as needed. These positions would start on July 1, 2004 or earlier if possible to ensure that at least one writing instructor would be available for consulting and planning during the summer period. Early Summer 2004: Also as part of Option C, the coordinating committee would create guidelines for the transformative course initiatives, issue a call for and seek out proposals, and select eligible proposals for implementation. This timing would allow for work during the summer period to ensure readiness for Fall 2004. Summer 2004: We recommend that steps be taken in June and July 2004 to set up a bridging process for mounting some of the nine non-credit WRT courses (Option B) in Spring 2005, with full restoration to take place in 2005-6. Since the EQ funding has already been allocated for additional sections of 199Y courses, this will also require provision of OTO funding for the 2004-5 year (about $52,000 plus salary rises). Arrangements for hiring and administration of the courses could again be delegated to the college principals as in 2002-3. It is essential to complete hiring, room bookings, and arrangements for student enrolment before the start of the 2004-5 academic year so that students and relevant course instructors can be notified of the opportunity for the subsequent term. September 2004 - June 2005: Depending on the number of options implemented, the coordinating committee would schedule regular (though not necessarily frequent) meetings to monitor the types of writing experience and instruction being provided in Arts and Science. The committee would help formulate outcome measures and advise on setting up consistent and comparable systems of project evaluation. It might also undertake or commission studies of additional instructional opportunities, as outlined in the final section of this report. It should also look for opportunities to bring together Arts and Science faculty members and writing instructors to identify unfolding needs and communicate the availability of new resources and experience. 15 APPENDICES N.B. The material listed in these Appendices is provided as hard copy in a binder available in the Dean's Office, and will also be accessible online through the website "Stepping Up in Arts and Science" at http://www.artsandscience.utoronto.ca/docs APPENDIX A: Reports on Arts and Science Initiatives and Projects, 1999-present 1. Reports on Pilot Projects 1999-2000 (approximate budget, $79,000): • Summary report by Margaret Procter: outlines the eight projects undertaken, comments on challenges and gauges outcomes • See also detailed course reports as listed below a. AST251S: report by Michael Allen, course instructor b. CHM137Y: report by Lindsay Brooks, writing/ESL TA c. BIO250Y: report and proposal by course instructors Michelle French, Anne Cordon, Michele Heath d. BIO320 and other courses: report and proposal by Helen Rodd, course instructor e. ENV200Y: report by Margaret Procter (including focus-group report by Cynthia Messenger) f. PHY256Y: report by Margaret Procter and focus-group report by Cynthia Messenger) g. SOC203Y: report by Jack Veugelers, course instructor 2. Reports on Pilot Projects 2000-2001 (approximate budget $78,000): • Table summarizes findings from surveys, focus groups, specific studies • See also detailed course reports listed below and report of Evaluation Subcommittee a. AST251S: report by Michael Allen, course instructor b. BIO250Y: report by Michelle French and other instructors, May 2001. For extension of project into 2001-2, two focus-group reports prepared by Margaret Procter, Fall 2001; report prepared by Nina Jones and other instructors, Spring 2002 c. BIO319, 324, 496: reports by Stephanie Halldorson, writing TA; Helen Rodd, course instructor d. ENV200Y: focus-group report prepared by facilitator Susannah Bunce e. HUM101Y: report by Maria Subtelny, course coordinator f. PHY256Y: report on focus group, Susannah Bunce, facilitator g. SOC203Y: report by Jack Veugelers, course instructor h. Survey of course TAs: report by Margaret Procter i. Report of Evaluation subcommittee: chair Lorne Tepperman 3. • Faculty handout, "Teaching Writing within Arts and Science Courses: Lessons from Experience," June 2001 Prepared by Best Practices subcommittee (Margaret Procter, chair) as an account of good teaching practices identified in the pilot projects. It provides links to a set of selected 16 • examples online (e.g., student manual Writing in Physics, tutorial lesson from HUM101Y, grading rubric from SOC203Y) Distributed to all department chairs; still in circulation as a faculty handout and webfile (www.utoronto.ca/writing/artscilessons.html) 4. iWRITE initiative, 2001 - present • Courseware project commissioned by Writing Committee, Winter 2001, to address needs and instructional gaps identified by studies of pilot projects • Undertaken by Margaret Procter with assistance of Robert Luke (Ph.D. student, OISE), funded by Arts and Science (total $32,000, 2001-2) and two ITCDF grants (total $44,500, 2001-2), supported by RCAT, CHASS, CQuest • See www.utoronto.ca/writing/iwrite/demo.html for a description of its current development, including use by eight Arts and Science courses; see www.utoronto.ca/iwrite/manual.html for a course instructors' manual on setting up a course site • To explore current course sites, go to www.iwriteweb.net, choose course from menu, use login guest3 and password demo3 a. b. c. d. e. ITCDF Proposal, 2001 Progress Report 2002 Progress Report 2003 Progress Report 2004 Sample Evaluation Reports: -- BIO25OY, September 2002: longitudinal analysis of student work, Patricia Patchet-Golubev -- ENG185, July 2003: report on focus group of student users 5. Survey of Writing Required within Programs, Mariel O'Neill-Karch, July 2002 a. Questionnaire b. Table of numerical results 6. Report on Arts and Science Writing Centres, David Clandfield, 2002-3: a. Executive Summary, January 2003 b. Draft 4 of Report, November 2002 c. Proposal for Funding Increase, Spring 2003 7. a. b. c. d. e. f. Reports and Samples from WRT Courses: WRT300: Course evaluations, 1999-2003 WRT300: Sample course outlines (Debby Repka, Dena Taylor) WRT301: Course evaluations, 2002 and 2003 WRT301: Sample course outlines (Deborah Knott) WRT305: Course evaluations (to come) WRT305: Sample course outlines (to come) 17 APPENDIX B: Background Reports for Arts and Science Committees, 1998-present 1. ESL Issues: a. Types of instruction needed by ESL learners compared by types provided at U of T: prepared for Educational Advisory Committee by Margaret Procter, May 1998 b. Comparison of structure and methods for ESL teaching in comparable research universities: prepared for EAC by Mark James (Ph.D. student, Second-Language Education, OISE), March 2000 c. Supporting language development in all years: report of EAC subcommittee, David Clandfield, chair, February 2001 d. Pass-Fail Systems at Other Universities: prepared by Mariel O'Neill-Karch, July 2001 2. Program Assessment: a. "Review of Studies Evaluating WAC Initiatives": lengthy literature-review report prepared by Danita Mushkat, Ph.D. graduate in Sociology, as commissioned by the Evaluation subcommittee (Lorne Tepperman, chair), September 2001: 6-page summary report; 60 pages of notes summarizing the studies, reference list b. Annotated bibliography on evaluations of writing centres: prepared for David Clandfield and writing-centre directors, Summer 2002 3. Mandate and Structure of Writing Centres a. “College Writing Centres and Student Services: Collaboration and Integration,” background notes prepared for Wendy Rolph in study of college operations, November 2001 b. "Writing Centers at 10 US Comparators, Public Research Universities, (AAUP Peers)": note and annotated list showing role of writing centres in Writing Across the Curriculum initiatives in other research universities, prepared by Margaret Procter for David Clandfield's study, 2002 18 APPENDIX C: Samples of Informational and Advisory Material Relevant to Arts and Science Initiatives, 1999-2003 (Developed by Margaret Procter unless otherwise noted; most also available online: see especially links at www.utoronto.ca/writing/faculty.html) 1. General Information about Instructional Resources: a. Leaflet "Writing in Arts and Science," prepared yearly, printing cost subsidized by Provost's office 1997-2002, then Vice-President, Students, 2003 (c. $1,300 yearly for >10,000 copies) distributed to college registrars for all incoming students, to libraries and writing centres for other students; also sent to departments and programs as hard copies and PDF file b. Student handout, "Writing Centres: How We Work And How To Work With Us" (student handout distributed by course instructors, writing centres across university) 2. Informational and Advisory Material about ESL Resources: a. Student handout, "ESL Resources at the University of Toronto," September 2003 (updated yearly) b. List of postsecondary ESL courses available outside the university, April 2001 c. Faculty handout on best instructional practices, "Ways to Help Your ESL Students -- and Everyone Else in the Process" (prepared for EAC by David Clandfield and Margaret Procter, with advice from Alister Cumming, OISE), Spring 2001 3. Faculty and TA Handouts on Integrating Writing within Courses (see also "Ways to Help your ESL Students (above) and "Teaching Writing Within A&S Courses") a. "Designing Written Assignments and Presenting Them To Students" b. "Commenting On Student Papers— Effectively and Efficiently" c. "Deterring Plagiarism: Some Strategies" d. "Reference Material for Instructors" e. "Reference Material You Can Recommend to Students" (DC\Writing Initiative - Final Report on Writing 30Mar04.doc)