older adults and mental health: issues and

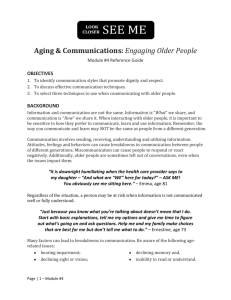

advertisement