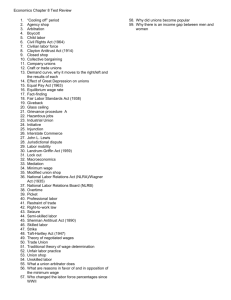

THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR COLLECTIVE BARGAINING IN

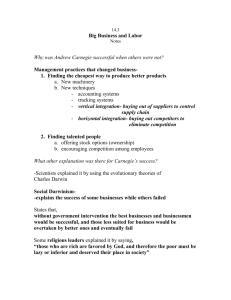

advertisement