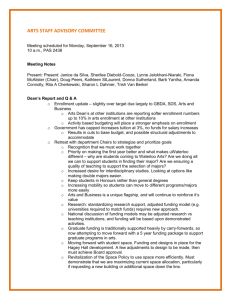

2012-2013 - Trinity College

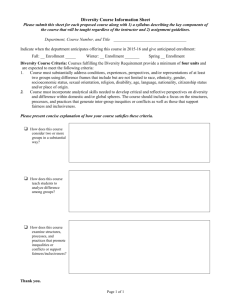

advertisement