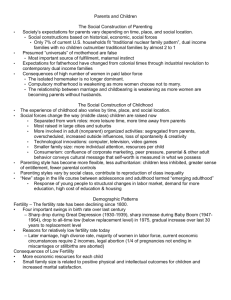

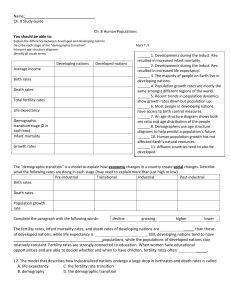

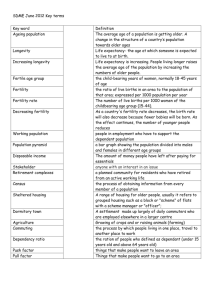

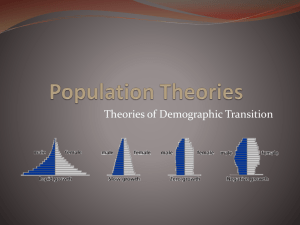

The new roles of men and women and implications for families and

advertisement