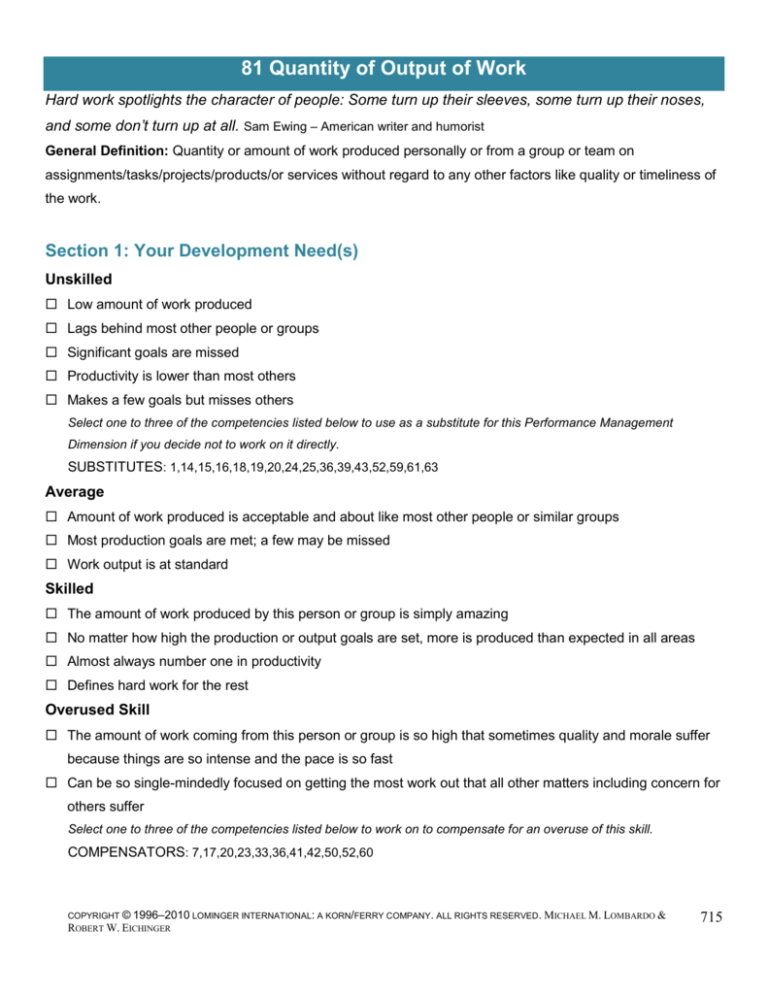

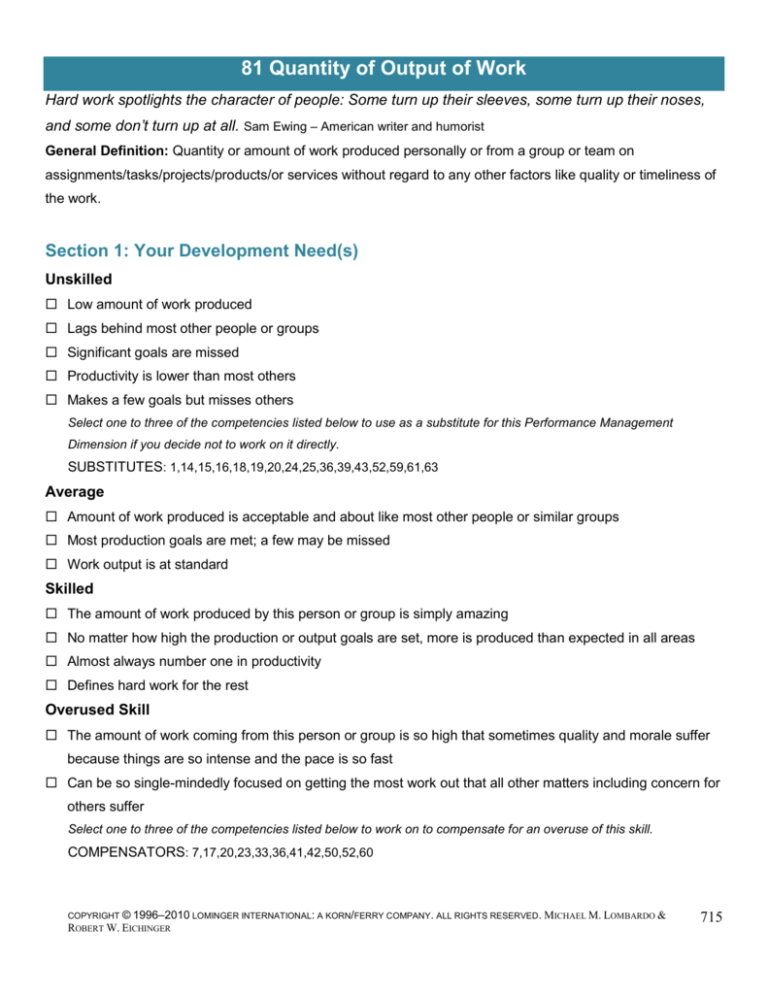

81 Quantity of Output of Work

Hard work spotlights the character of people: Some turn up their sleeves, some turn up their noses,

and some don‘t turn up at all. Sam Ewing – American writer and humorist

General Definition: Quantity or amount of work produced personally or from a group or team on

assignments/tasks/projects/products/or services without regard to any other factors like quality or timeliness of

the work.

Section 1: Your Development Need(s)

Unskilled

Low amount of work produced

Lags behind most other people or groups

Significant goals are missed

Productivity is lower than most others

Makes a few goals but misses others

Select one to three of the competencies listed below to use as a substitute for this Performance Management

Dimension if you decide not to work on it directly.

SUBSTITUTES: 1,14,15,16,18,19,20,24,25,36,39,43,52,59,61,63

Average

Amount of work produced is acceptable and about like most other people or similar groups

Most production goals are met; a few may be missed

Work output is at standard

Skilled

The amount of work produced by this person or group is simply amazing

No matter how high the production or output goals are set, more is produced than expected in all areas

Almost always number one in productivity

Defines hard work for the rest

Overused Skill

The amount of work coming from this person or group is so high that sometimes quality and morale suffer

because things are so intense and the pace is so fast

Can be so single-mindedly focused on getting the most work out that all other matters including concern for

others suffer

Select one to three of the competencies listed below to work on to compensate for an overuse of this skill.

COMPENSATORS: 7,17,20,23,33,36,41,42,50,52,60

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

715

Some Causes

Burned out

Fights bosses

Goals set too high

Lack of ambition

Lack of realistic resources

New to the job or field

Not aligned or committed

Not focused or disciplined

Not organized

Organization politics

Perfectionist

Procrastinator

The Map

There is probably no substitute for getting things done. Most rewards in life go to those who produce. Being

able to consistently produce covers a lot of other problems. Others are not very tolerant of excuses from those

who consistently don’t get things done. Once not getting things done surfaces as an issue, others begin to look

for the reasons and begin finding other problems—real and imagined. It’s a career death spiral. The best

course of action is to concentrate fully on reaching the goals and objectives set for the task, project or job you

are in or get out.

Section 2: Learning on Your Own

These self-development remedies will help you build your skill(s).

Some Remedies

1. Trouble setting priorities? Focus efforts on things that are tied to the bottom line. What’s missioncritical? What are the three to five things that most need to get done to achieve your goals? Effective

performers typically spend about half their time on a few mission-critical priorities. Don’t get diverted by

trivia and things you like doing but that aren’t tied to the bottom line. More help? – See #50 Priority Setting.

2. Unsure of the target? Set goals for yourself and others. Most people work better if they have a set of

goals and objectives to achieve and a standard everyone agrees to measure accomplishments against.

Most people like stretch goals. They like them even better if they have had a hand in setting them. Set

checkpoints along the way to be able to measure progress. Give yourself and others as much feedback as

you can. More help? – See #35 Managing and Measuring Work.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

716

3. Don’t know how to get results? Study best practices. Some don’t know the best way to produce

results. There is a well-established set of best practices for producing results—TQM, ISO and Six Sigma. If

you are not disciplined in how to design work flows and processes for yourself and others, buy one book on

each of these topics. Go to one workshop on efficient and effective work design. Ask those responsible for

total work systems in your organization for help. More help? – See #52 Process Management and #63

Total Work Systems (e.g., TQM/ISO/Six Sigma).

4. Organizing? Make a compelling case for more resources. Are you always short on resources?

Always pulling things together on a shoe string? Getting results means getting and using resources.

People. Money. Materials. Support. Time. Many times it involves getting resources you don’t control. You

have to beg, borrow, but hopefully not steal. That means negotiating, bargaining, trading, cajoling, and

influencing. What’s the business case for the resources you need? What do you have to trade? How can

you make it a win for everyone? More help? – See #37 Negotiating and #39 Organizing.

5. Getting work done through others? Learn what it takes to be a good manager. Some people are

not good managers of others. They can produce results by themselves but do less well when the results

have to come from the team. Are you having trouble getting your team to work with you to get the results

you need? You have the resources and the people but things just don’t run well. Maybe you do too much

work yourself. You don’t delegate or empower. You don’t communicate well. You don’t motivate well. You

don’t plan well. You don’t set priorities and goals well. If you are a struggling manager or a first-time

manager, there are well-known and documented principles and practices of good managing. Do you share

credit? Do you paint a clear picture of why this is important? Is their work challenging? Do you inspire or

just hand out work? Read Becoming a Manager by Linda A. Hill. Go to one course on management. More

help? – See #18 Delegation, #20 Directing Others, #36 Motivating Others, and #60 Building Effective

Teams.

6. Working across borders and boundaries? Appeal to the common good. Do you have trouble when

you have to go outside your unit to reach your goals and objectives? This means that influence skills,

understanding, and trading are the currencies to use. Don’t just ask for things; find some common ground

where you can provide help. What do the peers you’re contacting need? Are your results important to

them? How does what you’re working on affect their results? If it affects them negatively, can you trade

something, appeal to the common good, figure out some way to minimize the work—volunteering staff

help, for example? Go into peer relationships with a trading mentality. To be seen as more cooperative,

always explain your thinking and invite them to explain theirs. Generate a variety of possibilities first rather

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

717

than stake out positions. Be tentative, allowing them room to customize the situation. Focus on common

goals, priorities and problems. Invite criticism of your ideas. More help? – See #42 Peer Relationships.

7. Not bold enough? Take a chance. Won’t take a risk? Sometimes producing results involves pushing

the envelope, taking chances and trying bold new initiatives. Doing those things leads to more misfires and

mistakes but also better results. Treat any mistakes or failures as chances to learn. Nothing ventured,

nothing gained. Up your risk comfort. Start small so you can recover more quickly. See how creative and

innovative you can be. Satisfy yourself; people will always say it should have been done differently. Listen

to them, but be skeptical. Conduct a postmortem immediately after finishing. This will indicate to all that

you’re open to continuous improvement whether the result was stellar or not. More help? – See #2 Dealing

with Ambiguity, #14 Creativity, #28 Innovation Management, and #57 Standing Alone.

8. Procrastinator? Pace yourself. Are you a lifelong procrastinator? Do you perform best in crises and

impossible deadlines? Do you wait until the last possible moment? If you do, you will miss deadlines and

performance targets. You might not produce consistent results. Some of your work will be marginal

because you didn’t have the time to do it right. You settled for a ―B‖ when you could have gotten an ―A‖ if

you had one more day to work on it. Start earlier. Always do 10% of each task immediately after it is

assigned so you can better gauge what it is going to take to finish the rest. Divide tasks and assignments

into thirds and schedule time to do them spaced over the delivery period. Always leave more time than you

think it’s going to take. More help? – See #47 Planning and #62 Time Management.

9. Lack perseverance? Tackle obstacles. Are you prone to give up on tough or repetitive tasks, have

trouble going back the second and third time, lose motivation when you hit obstacles? Trouble making that

last push to get it over the top? Attention span is shorter than it needs to be? Set mini-deadlines. Break

down the task into smaller pieces so you can view your progress more clearly. Switch approaches. Do

something totally different next time. Have five different ways to get the same outcome. Be prepared to do

them all when obstacles arise. Task trade with someone who has your problem. Work on each other’s

tasks. More help? – See #43 Perseverance.

10. Feeling stressed or strained? Adjust your perspective. Producing results day after day, quarter

after quarter, year after year is stressful. Some people are energized by moderate stress. They actually

work better. Some people are debilitated by stress. They decrease in productivity as stress increases. Are

you close to burnout? Dealing with stress and pressure is a known technology. Stress and pressure are

actually in your head, not in the outside world. Some people are stressed by the same events others are

energized by—losing a major account. Some people cry and some laugh at the same external event—

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

718

someone slipping on a banana peel. Stress is how you look at events, not the events themselves. Dealing

more effectively with stress involves reprogramming your interpretation of your work and about what you

find stressful. There was a time in your life when spiders and snakes were life threatening and stressful to

you. Are they now? Talk to your boss or mentor about getting some relief if you’re about to crumble. Maybe

this job isn’t for you. Think about moving back to a less stressful job. More help? – See #6 Career Ambition

and #11 Composure.

Section 3: Learning from Feedback

These sources would give you the most accurate and detailed feedback on your skill(s).

1. Direct Reports

Across a variety of settings, your direct reports probably see you the most. They are the recipients of most

of your managerial behaviors. They know your work. They can compare you with former bosses. Since

they may hesitate to give you negative feedback, you have to set the atmosphere to make it easier for

them. You have to ask.

2. Direct Boss

Your direct boss has important information about you, your performance, and your prospects. The

challenge is to get this information. There are formal processes (e.g., performance appraisals). There are

day-to-day opportunities. To help, signal your boss that you want and can handle direct and timely

feedback. Many bosses have trouble giving feedback, so you will have to work at it over a period of time.

3. Past Associates/Constituencies

When confronted with a present performance problem, some claim, ―I wasn’t like that before; it must be the

current situation.‖ When feedback is available from former associates, about 50% support that claim. In the

other half of the cases, the people were like that before and probably didn’t know it. It sometimes makes

sense to access the past to clearly see the present.

4. Peers and Colleagues

Peers and colleagues have a special social and working relationship. They attend staff meetings together,

share private views, get feedback from the same boss, travel together, and are knowledgeable about each

other’s work. You perhaps let your guard down more around peers and act more like yourself. They can be

a valuable source of feedback.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

719

5. Yourself

You are an important source of feedback on yourself. But some caution is appropriate. If you have not

received much feedback, you may be less accurate than the other sources. We all have blind spots,

defense shields, ideal self-views, and fantasies. Before acting on your own self-views, get outside

confirmation from other appropriate sources.

Section 4: Learning from Develop-in-Place Assignments

These part-time develop-in-place assignments will help you build your skill(s).

Manage a group of people involved in tackling a fix-it or turnaround project.

Manage a group of resistant people with low morale through an unpopular change or project.

Manage a group of low-competence or low-performing people through a task they couldn’t do by

themselves.

Relaunch an existing product or service that’s not doing well.

Assign a project with a tight deadline to a group.

Help shut down a plant, regional office, product line, business, operation, etc.

Launch a new product, service, or process.

Manage a group through a significant business crisis.

Work a few shifts in the telemarketing or customer service department, handling complaints and inquiries

from customers.

Plan a new site for a building (plant, field office, headquarters, etc.).

Section 5: Learning from Full-Time Jobs

These full-time jobs offer the opportunity to build your skill(s).

1. Fix-Its/Turnarounds

The core demands to qualify as a Fix-it or Turnaround assignment are: (1) Clean-ing up a mess. (2)

Serious people issues/problems like credibility/performance/morale. (3) Tight deadline. (4) Serious

business performance failure. (5) Last chance to fix. Four types of Fix-its/Turnarounds: (1) Fixing a failed

business/unit involving taking control, stopping losses, managing damage, planning the turnaround, dealing

with people problems, installing new processes and systems, and rebuilding the spirit and performance of

the unit. (2) Managing sizable disasters like mishandled labor negotiations and strikes, thefts, history of

significant business losses, poor staff, failed leadership, hidden problems, fraud, public relations

nightmares, etc. (3) Significant reorganization and restructuring (e.g., stabilizing the business, re-forming

unit, introducing new systems, making people changes, resetting strategy and tactics). (4) Significant

system/process breakdown (e.g., MIS, financial coordination processes, audits, standards, etc.) across

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

720

units requiring working from a distant position to change something, providing advice and counsel, and

installing or implementing a major process improvement or system change outside your own unit and/or

with customers outside the organization.

2. Scale Assignments

Core requirements to qualify as a Scale (size) shift assignment are: (1) Sizable jump/shift in the size of the

job in areas like number of people, number of layers in organization, size of budget, number of locations,

volume of activity, tightness of deadlines. (2) Medium to low complexity; mostly repetitive and routine

processes and procedures. (3) Stable staff and business. (4) Stable operations. (5) Often slow, steady

growth. Examples of Scale assignments would be: (1) Managing one function for entire enterprise. (2)

Responsibility for one product area or one geography that is expanding. (3) Leading an enterprise-wide

project. (4) Moving from district to regional manager.

3. Start-Ups

The core demands to qualify as a start from scratch are: (1) Starting something new for you and/or for the

organization. (2) Forging a new team. (3) Creating new systems/facilities/staffs/programs/procedures. (4)

Contextual adversity (e.g., uncertainty, government regulation, unions, difficult environment). Seven types

of start from scratches: (1) Planning, building, hiring, and managing (e.g., building a new facility, opening

up a new location, moving a unit or company). (2) Heading something new (e.g., new product, new service,

new line of business, new department/function, major new program). (3) Taking over a

group/product/service/program that had existed for less than a year and was off to a fast start. (4)

Establishing overseas operations. (5) Implementing major new designs for existing systems. (6) Moving a

successful program from one unit to another. (7) Installing a new organization-wide process as a full-time

job like Total Work Systems (e.g., TQM/ISO/Six Sigma).

Section 6: Learning from Your Plan

These additional remedies will help make this development plan more effective for you.

Learning to Learn Better

1. Teach Others Something You Know Well

Teach someone to do something you know how to do to check out your own thinking, knowledge, and

rules. Watch in detail how others learn; the process will require breaking down your patterns into teachable

steps.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

721

2. Commit to a Tight Time Frame to Accomplish Something

Set some specific goals and tighter-than-usual time frames for yourself, and go after them with all you’ve

got. Push yourself to stick to the plan; get more done than usual by adhering to a tight plan.

3. Study People Who Have Successfully Done What You Need to Do

Interview people who have already done what you’re planning to do and check your plan against what they

did. Try to summarize their key tactics, strategies, and insights; adjust your plan accordingly.

4. Plan Backwards from the Ideal

Envision what an ideal outcome would look like and plan backwards. What is the series of events that

would have to take place to get there? What would people do? What would have to be done? How would

people react? How would things play out? Could you plan it forward and get to the same outcome?

5. Rehearse Successful Tactics/Strategies/Actions

Mentally rehearse how you will act before going into the situation. Try to anticipate how others will react,

what they will say, and how you’ll respond. Check out the best and worst cases; play out both scenes.

Check your feelings in conflict or worst-case situations; rehearse staying under control.

6. Study Yourself in Detail

Study your likes and dislikes because they can drive a lot of your thinking, judging, and acting. Ask which

like or dislike has gotten in the way or prevented you from moving to a higher level of learning. Are your

likes and dislikes really important to you or have you just gone on ―autopilot‖? Try to address and

understand a blocking dislike and change it.

7. Do Something on Gut Feel More Than Analysis

Act on ―gut feel‖; go with your hunches instead of careful planning. Take a chance on a solution; take some

risks; try a number of things by trial and error and learn to deal with making some mistakes.

8. Sort Through Information in Multiple Ways

Collect the data and arrange it in elements or pieces. Create definitions and arrange the data in various

ways: chronologically, from most to least, from biggest to smallest, from cold to hot, what you know most

about and least about, from known to unknown, etc., until the meaning becomes obvious.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

722

Learning from Experience, Feedback, and Other People

9. Learning from Bosses

Bosses can be an excellent and ready source for learning. All bosses do some things exceptionally well

and other things poorly. Distance your feelings from the boss/direct report relationship and study things that

work and things that don’t work for your boss. What would you have done? What could you use and what

should you avoid?

10. Learning from Interviewing Others

Interview others. Ask not only what they do, but how and why they do it. What do they think are the rules of

thumb they are following? Where did they learn the behaviors? How do they keep them current? How do

they monitor the effect they have on others?

What we think or what we believe is, in the end, of little consequence. The only thing of consequence

is what we do. John Ruskin – English art critic and historian

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

723

Suggested Readings

Bellman, G. M. (2001). Getting things done when you are not in charge (2nd ed.). San Francisco: BerrettKoehler Publishers.

Block, P. (2002). The answer to how is yes: Acting on what matters. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler

Publishers.

Bossidy, L., & Charan, R. (with Burck, C.). (2002). Execution: The discipline of getting things done. New York:

Crown Business.

Carrison, D. (2003). Deadline! How premier organizations win the race against time. New York: AMACOM.

Cramer, K. D. (2002). When faster harder smarter is not enough: Six steps for achieving what you want in a

rapid-fire world. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Crouch, C. (2008). Being productive: Learning how to get more done with less effort. Memphis, TN: Dawson.

Gorman, T. (2007). Execution: Create the vision. Implement the plan. Get the job done. Avon, MA: Adams

Media.

Hill, L. A. (2003). Becoming a manager: How new managers master the challenges of leadership (2nd ed.).

New York: Harvard Business School Press.

Hutchings, P. J. (2002). Managing workplace chaos: Solutions for handling information, paper, time, and

stress. New York: AMACOM.

James, N. (2006). Secrets of super-productivity: How to achieve amazing things in your work life. Doylestown,

PA: Neen James Communications.

Lefton, R. E., & Loeb, J. T. (2004). Why can‘t we get anything done around here? The smart manager‘s guide

to executing the work that delivers results. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Loehr, J., & Schwartz, T. (2003). The power of full engagement: Managing energy, not time, is the key to high

performance and personal renewal. New York: Free Press.

Markel, G. (2008). Defeating the 8 demons of distraction: Proven strategies to increase productivity and

decrease stress. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse.

McMahon, G., & Rosen, A. (2008, May). Why perfectionism at work does not pay. Training Journal, 60-63.

Niven, P. R. (2006). Balanced scorecard step-by-step: Maximizing performance and maintaining results (2nd

ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Ozyasar, H. (2006). When time management fails: How efficient managers create more value with less work.

Charleston, SC: Booksurge.

Panella, V. (2002). The 26-hour day: How to gain at least two hours a day with time control. Franklin Lakes,

NJ: Career Press.

Prosen, B. (2007). How leaders increase accountability & results. Supervision, 68(3), 13-15.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

724

Ramsey, R. (2008). 15 Time wasters for supervisors. Supervision, 69(3), 16-18.

Syed, M. (2010). Bounce: Mozart, Federer, Picasso, Beckham, and the science of success. New York:

HarperCollins.

Whipp, R., Adam, B., & Sabelis, I. (Eds.). (2002). Making time: Time and management in modern

organizations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Zabriskie, K. (2009). Taming the time monster: How to stop procrastinating, start planning, and get more done.

Buffalo, NY: Full Court Press.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

725