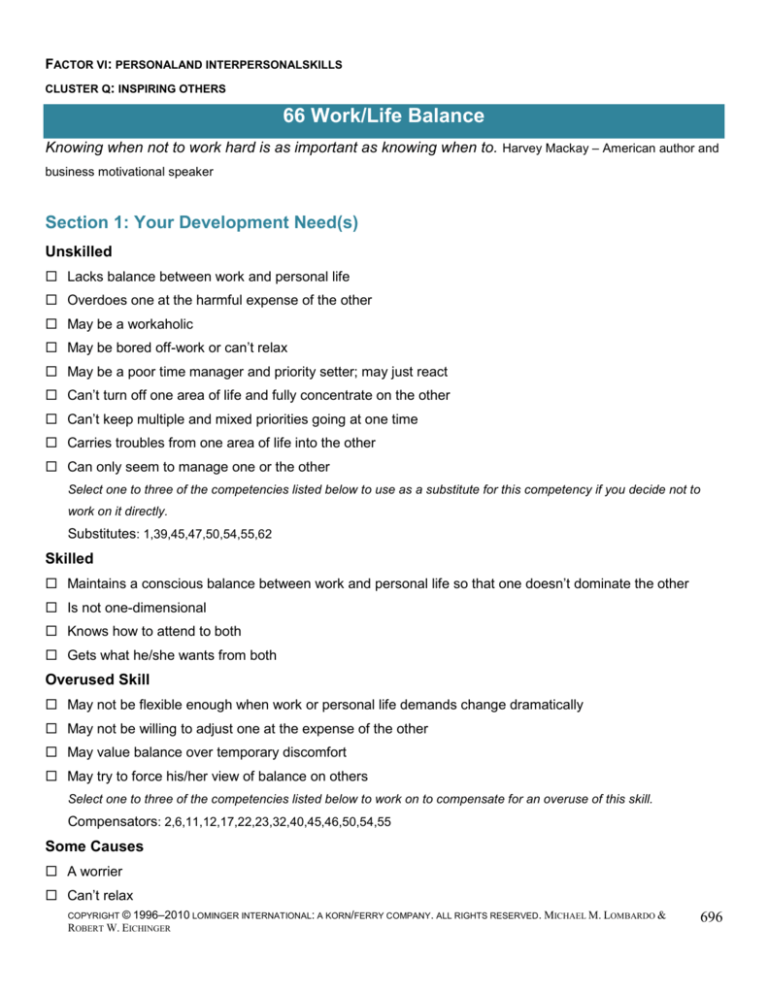

FACTOR VI: PERSONALAND INTERPERSONALSKILLS

CLUSTER Q: INSPIRING OTHERS

66 Work/Life Balance

Knowing when not to work hard is as important as knowing when to. Harvey Mackay – American author and

business motivational speaker

Section 1: Your Development Need(s)

Unskilled

Lacks balance between work and personal life

Overdoes one at the harmful expense of the other

May be a workaholic

May be bored off-work or can’t relax

May be a poor time manager and priority setter; may just react

Can’t turn off one area of life and fully concentrate on the other

Can’t keep multiple and mixed priorities going at one time

Carries troubles from one area of life into the other

Can only seem to manage one or the other

Select one to three of the competencies listed below to use as a substitute for this competency if you decide not to

work on it directly.

Substitutes: 1,39,45,47,50,54,55,62

Skilled

Maintains a conscious balance between work and personal life so that one doesn’t dominate the other

Is not one-dimensional

Knows how to attend to both

Gets what he/she wants from both

Overused Skill

May not be flexible enough when work or personal life demands change dramatically

May not be willing to adjust one at the expense of the other

May value balance over temporary discomfort

May try to force his/her view of balance on others

Select one to three of the competencies listed below to work on to compensate for an overuse of this skill.

Compensators: 2,6,11,12,17,22,23,32,40,45,46,50,54,55

Some Causes

A worrier

Can’t relax

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

696

Off-work is not exciting

Overly ambitious

Poor priority setting

Time management

Too intense

Workaholic

Leadership Architect® Factors and Clusters

This competency is in the Personal and Interpersonal Skills Factor (VI). This competency is in the Balancing

Work/Life Cluster (U). You may want to check other competencies in the same Factor/Cluster for related tips.

The Map

Research on well-being shows that the best adjusted people are generally the busiest people, on- and offwork. Balance is not achieved only by people who are not busy and have the time. It’s the off-work part of

balance that gives most people problems. With downsizing, wondering if you’ll be in the next layoff, and 60

hour work weeks, many people are too exhausted to do much more than refuel off-work. Nonetheless,

frustration and feeling unidimensional are often the result of not forcing the issue of balance in one’s life. There

is special pressure on those with full dual responsibilities—they have full-time jobs and they have full-time care

giver and home management duties.

Section 2: Learning on Your Own

These self-development remedies will help you build your skill(s).

Some Remedies

1. Overcommitting? Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Add things to your off-work life. This was a

major finding of a stress study at AT&T of busy, high-potential women and men. It may seem

counterintuitive, but the best adjusted people forced themselves to structure off-work activities just as much

as on-work activities. Otherwise work drives everything else out. Those with dual responsibilities (primary

care giver and home manager and a full-time job holder) need to use their management strengths and

skills more at home. What makes your work life successful? Batch tasks, bundle similar activities together,

delegate to children or set up pools with coworkers or neighbors to share tasks such as car pooling, soccer

games, Scouts, etc. Pay to have some things done that are not mission-critical to your home needs.

Organize and manage efficiently. Have a schedule. Set up goals and plans. Use some of your work skills

more off-work.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

697

2. Not sure how to define balance? Learn what works for you. Balance has nothing to do with 50/50 or

clock time. It has to do with how we use the time we have. It doesn’t mean for every hour of work, you must

have an hour off-work. It means finding what is a reasonable balance for you. Is it a few hours a week

unencumbered by work worries? Is it four breaks a day? Is it some solitude before bedtime? Is it playing

with your kids more? Is it having an actual (rather than ―Did you remember the dry cleaning?‖) conversation

with your spouse (partner) each day? Is it a community, religious or sports activity that you’re passionate

about? Schedule them; structure them into your life. Negotiate with your partner; don’t just accept your life

as a given. Define what balance is for you and include your spouse or friends or family in the definition.

3. Weighed down? Concentrate on the present. There’s time and there’s focused time. Busy people with

not much time learn to get into the present tense without carrying the rest of their burdens, concerns and

deadlines with them. When you have only one hour to read or play with the kids or play racquetball or

sew—be there. Have fun. You won’t solve any problems during the 60 minutes anyway. Train your mind to

be where you are. Focus on the moment.

4. Leaving your strengths behind? Create deadlines, urgencies, and structures off-work. One tactic

that helps is for people to use their strengths from work off-work. If you are organized, organize something.

If you are very personable, get together a regular group. If you are competitive, set up a regular match. As

commonsensical as this seems, AT&T found that people with poor off-work lives did not use their strengths

off-work. They truly left them at the office.

5. Can’t say no? Recognize you can’t do it all. What are your NOs? If you don’t have any, chances are

you’ll be frustrated on both sides of your life. Part of maturity is letting go of nice, even fun and probably

valuable, activities. What are you hanging on to? What can’t you say no to at the office that really isn’t a

priority? Where do you make yourself a patsy? If your saying no irritates people initially, this may be the

price. You can usually soften it, however, by explaining what you are trying to do. Most people won’t take it

personally if you say you’re going to pick up your child or maybe coach his/her soccer team or you can’t

help with this project because of an explicit priority which is critical to your unit. Give reasons that don’t

downgrade the activity you’re giving up. It’s not that it’s insignificant; it just didn’t quite make the cut.

6. Bored? Make your off-work life more exciting. Many of us want as little stress as we can get off-work

and seeking this comfort ends up as boredom. What are three really exciting things you and/or your family

could do? Work will always be exciting or at least full of activity. Combating this stimulus overload means

finding something you can be passionate about off the job.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

698

7. Can’t get your mind off work? If you can’t relax once you leave work, schedule breakpoints or

boundaries. One of the great things about the human brain is that it responds to change; signal it that

work is over—play music in your car, immediately play with your children, go for a walk, swim for 20

minutes—give your mind a clear and repetitious breakpoint. Try to focus all your energy where you are. At

work, worry about work things and not life things. When you hit the driveway, worry about life things and

leave work things at the office. Schedule a time every week for financial management and worries. Try to

concentrate your worry time where it will do some good.

8. Unable to let go? Compartmentalize. If your problem goes beyond that—you’re three days into

vacation and still can’t relax—write down what you’re worried about, which is almost always unresolved

problems. Write down everything you can think of. Don’t worry about complete sentences—just get it down.

You’ll usually find it’s hard to fill a page and there will be only three topics—work problems, problems with

people, and a to-do list. Note any ideas that come up for dealing with them. This will usually shut off your

worry response, which is nothing but a mental reminder of things unresolved. Since we’re all creatures of

habit, though, the same worries will pop up again. Then you have to say to yourself (as silly as this seems),

―I’ve done everything I can do on that right now,‖ or ―That’s right, I remember, I’ll do it later.‖ Obviously, this

tactic works when we’re not on vacation as well.

9. Do you truly live to work? If you love work, and you’re really a happy but unbalanced workaholic,

try tip #4. If that doesn’t work, you need to see yourself 20 years from now. Find three people who remind

you of you but are 20 years older. Are they happy? How are their personal lives? Any problems with stress

or depression? If this is OK with you, protect yourself with #7. If you don’t do something to refresh yourself,

your effectiveness will eventually suffer or you’ll burn out.

10. Not sure what to do? Talk to people who have your best interests at heart. Seek counsel from

those who accept you for who you are and with whom you can be candid. What do they want for you? Ask

them how they would change your balance.

Section 3: Learning from Feedback

These sources would give you the most accurate and detailed feedback on your skill(s).

1. Development Professionals

Sometimes it might be valuable to get some analysis and feedback from a professional trained and certified

in the area you’re working on—possibly a career counselor, a therapist, clergy, a psychologist, etc.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

699

2. Direct Reports

Across a variety of settings, your direct reports probably see you the most. They are the recipients of most

of your managerial behaviors. They know your work. They can compare you with former bosses. Since

they may hesitate to give you negative feedback, you have to set the atmosphere to make it easier for

them. You have to ask.

3. Family Members

On some issues like interpersonal style or compassion, it might be helpful to ask various and multiple

family members for feedback to add confirmation or context to feedback you’ve received in the workplace.

4. Natural Mentors

Natural mentors have a special relationship with you and are interested in your success and your future.

Since they are usually not in your direct chain of com-mand, you can have more open, relaxed, and fruitful

discussions about yourself and your career prospects. They can be a very important source for candid or

critical feedback others may not give you.

5. Yourself

You are an important source of feedback on yourself. But some caution is appropriate. If you have not

received much feedback, you may be less accurate than the other sources. We all have blind spots,

defense shields, ideal self-views, and fantasies. Before acting on your own self-views, get outside

confirmation from other appropriate sources.

Section 4: Learning from Develop-in-Place Assignments

These part-time develop-in-place assignments will help you build your skill(s).

Attend a self-awareness/assessment course that includes feedback.

Join a self-help or support group.

Complete a self-study course or project in an important area for you.

Attend a course or event which will push you personally beyond your usual limits or outside your comfort

zone (e.g., Outward Bound, language immersion training, sensitivity group, public speaking).

Act as a loaned executive to a charity, government agency, etc.

Become an active member of a professional organization.

Work on a project that involves travel and study of an international issue, acquisition, or joint venture and

report back to management.

Represent the organization at a trade show, convention, exposition, etc.

Assign a project with a tight deadline to a group.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

700

Take over for someone on vacation, leave of absence, or on a long trip.

Section 5: Learning from Full-Time Jobs

These full-time jobs offer the opportunity to build your skill(s).

1. Cross-Moves

The core demands necessary to qualify as a Cross-Move are: (1) Move to a very different set of

challenges. (2) Abrupt jump/shift in tasks/activities. (3) Never been there before. (4) New setting/conditions.

Examples of Cross-Moves are: (1) Changing divisions. (2) Changing functions. (3) Field/headquarters

shifts. (4) Line/staff switches. (5) Country switches. (6) Working with all new people. (7) Changing lines of

business.

2. International Assignments

The core demands to qualify as an International assignment are: (1) First-time working in the country. (2)

Significant challenges like new language, hardship location, unique business rules/practices, significant

cultural/marketplace differences, different functional task, etc. (3) More than a year assignment. (4) No

automatic return deal. (5) Not necessarily a change in job challenge, technical content, or responsibilities.

Examples of International assignments would be: (1) Managing local operations for an office located

outside your home country. (2) Leading the expansion into new global markets. (3) International sales

position. (4) Country/region head. (5) Managing transition for outsourced operations at an international

location. (6) Head of supply chain or manufacturing for global business. (7) Global compliance manager at

an international post.

3. Staff to Line Shifts

Core demands necessary to qualify for a Staff to Line shift are: (1) Moving to a job with an easily

determined bottom line or results. (2) Managing bigger scope and/or scale. (3) Requires new

skills/perspectives. (4) Unfamiliar aspects of the assignment. Examples of Staff to Line shifts would be: (1)

Moving from support function to business unit with P&L responsibility. (2) Product manager responsible for

product life cycle, revenue projections, and inventory planning. (3) General manager position. (4) Manager

responsible for a region or a product line or brand.

Section 6: Learning from Your Plan

These additional remedies will help make this development plan more effective for you.

Learning to Learn Better

1. Study Yourself in Detail

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

701

Study your likes and dislikes because they can drive a lot of your thinking, judging, and acting. Ask which

like or dislike has gotten in the way or prevented you from moving to a higher level of learning. Are your

likes and dislikes really important to you or have you just gone on ―autopilot‖? Try to address and

understand a blocking dislike and change it.

Learning from Experience, Feedback, and Other People

2. Learning from Ineffective Behavior

Seeing things done poorly can be a very potent source of learning for you, especially if the behavior or

action affects others negatively. Many times the thing done poorly causes emotional reactions or pain in

you and others. Distance yourself from the feelings and explore why the actions didn’t work.

3. Learning from Interviewing Others

Interview others. Ask not only what they do, but how and why they do it. What do they think are the rules of

thumb they are following? Where did they learn the behaviors? How do they keep them current? How do

they monitor the effect they have on others?

4. Learning from Observing Others

Observe others. Find opportunities to observe without interacting with your model. This enables you to

objectively study the person, note what he/she is doing or not doing, and compare that with what you would

typically do in similar situations. Many times you can learn more by watching than asking. Your model may

not be able to explain what he/she does or may be an unwilling teacher.

5. Feedback in Unusual Contexts/Situations

Temporary and extreme conditions and contexts may shade interpretations of your behavior and intentions.

Demands of the job may drive you outside your normal mode of operating. Hence, feedback you receive

may be inaccurate during those times. However, unusual contexts affect our behavior less than most

assume. It’s usually a weak excuse.

If A is a success in life, then A equals x plus y plus z. Work is x; y is play; and z is keeping your mouth

shut. Albert Einstein – German-born Nobel Prize-winning physicist

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

702

Suggested Readings

Alboher, M. (2007). One person/multiple careers: A new model for work/life success. Boston: Business Plus.

Barsh, J., Cranston, S., & Lewis, G. (2009). How remarkable women lead: The breakthrough model for work

and life. New York: Crown Business.

Bogle, J. C. (2008). Enough: True measures of money, business, and life. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Cohen, D., & Prusak, L. (2001). In good company: How social capital makes organizations work. Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Deering, A., Dilts, R., & Russell, J. (2002). Alpha leadership: Tools for business leaders who want more from

life. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Ferriss, T. (2007). The 4-hour workweek: Escape 9–5, live anywhere, and join the new rich. New York: Crown

Publishing Group.

Germer, F. (2001). Hard won wisdom: More than 50 extraordinary women mentor you to find self-awareness,

perspective, and balance. New York: Perigee.

Glanz, B. (2003). Balancing acts. Chicago: Dearborn Trade.

Gordon, G. E. (2001). Turn it off: How to unplug from the anytime-anywhere office without disconnecting your

career. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Hakim, C. (2000). Work-lifestyle choices in the 21st century: Preference theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University

Press.

Harvard Business School Press. (2000). Harvard Business Review on work and life balance. Boston: Harvard

Business School Press.

Jackson, M. (2002). What‘s happening to home: Balancing work, life and refuge in the information age. Notre

Dame, IN: Sorin Books.

Johnson, T., & Spizman, R. F. (2008). Will work from home: Earn the cash—without the commute. New York:

Berkley Publishing Group.

Lewis, S., & Cooper, C. L. (2005). Work-life integration: Case studies of organizational change. West Sussex,

England: John Wiley & Sons.

Mainiero, L. A., & Sullivan, S. E. (2006). The opt-out revolt: Why people are leaving companies to create

kaleidoscope careers. Mountain View, CA: Davies-Black.

Matthews, J., & Dennis, J. (2003). Lessons from the edge: Survival skills for starting and growing a company.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Merrill, A. R., & Merrill, R. R. (2003). Life matters: Creating a dynamic balance of work, family, time and

money. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Muna, F. A., & Mansour, N. (2009). Balancing work and personal life: The leader as acrobat. Journal of

Management Development, 28(2), 121-133.

Peterson, B. D., & Nielson, G. W. (2009). Fake work: Why people are working harder than ever but

accomplishing less, and how to fix the problem. New York: Simon Spotlight Entertainment.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

703

Rao, S. (2010). Happiness at work: Be resilient, motivated, and successful—No matter what. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Sawi, B. (2000). Coming up for air: How to build a balanced life in a workaholic world. New York: Hyperion.

Snow, P. (2010). Creating your own destiny: How to get exactly what you want out of life and work (Rev. ed.).

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

St. James, E. (2001). Simplify your work life: Ways to change the way you work so you have more time to live.

New York: Hyperion.

Swindall, C. (2010). Living for the weekday: What every employee and boss needs to know about enjoying

work and life. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Williams, J. (2000). Unbending gender: Why family and work conflict and what to do about it. Oxford, UK:

Oxford University Press.

COPYRIGHT © 1996–2010 LOMINGER INTERNATIONAL: A KORN/FERRY COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MICHAEL M. LOMBARDO &

ROBERT W. EICHINGER

704